The document discusses light interaction with atoms and molecules, including:

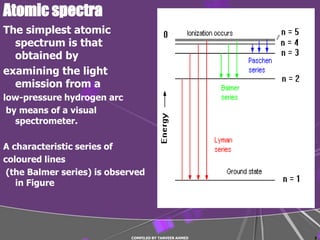

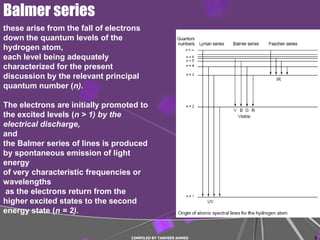

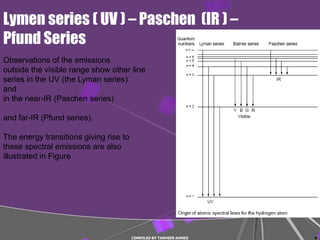

1) Atomic spectra such as the Balmer series arise from electrons falling to lower energy levels in hydrogen atoms.

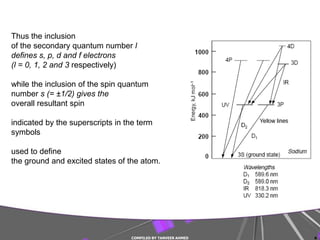

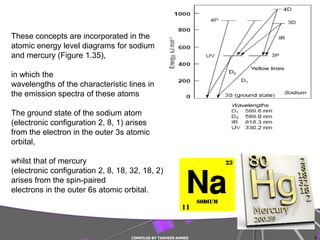

2) More complex atoms like sodium and mercury require additional quantum numbers to describe their emission spectra.

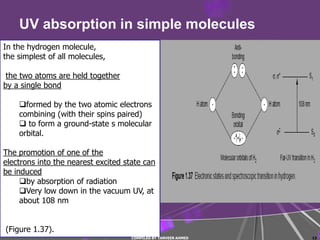

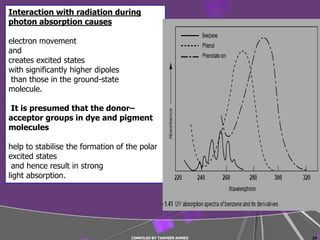

3) Simple molecules like hydrogen absorb UV light when electrons are promoted between molecular orbitals.

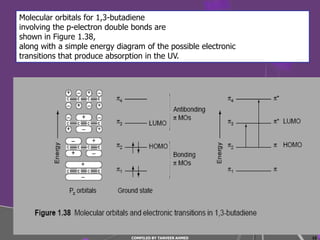

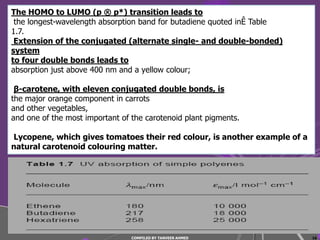

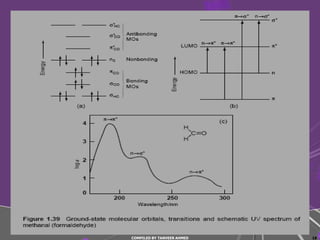

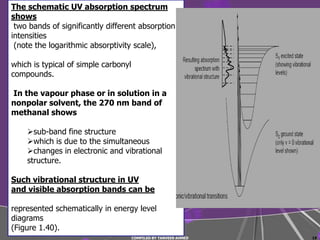

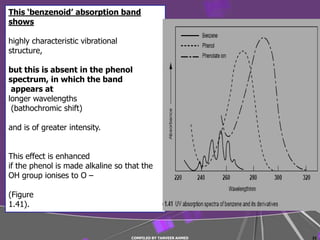

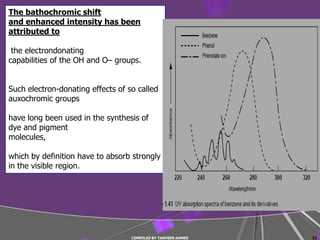

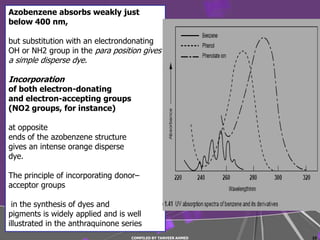

4) Conjugated systems and heteroatoms in molecules like butadiene and formaldehyde shift absorption to longer wavelengths.