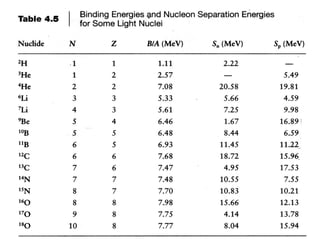

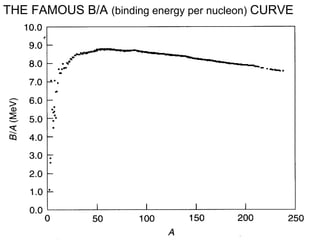

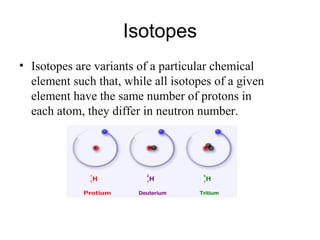

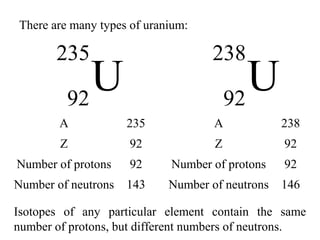

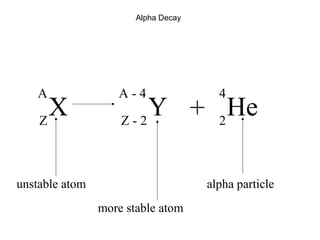

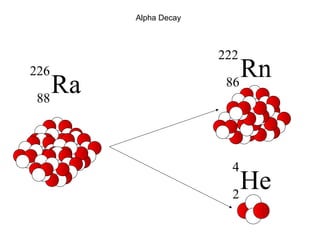

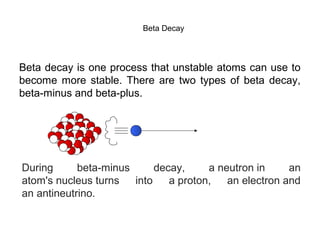

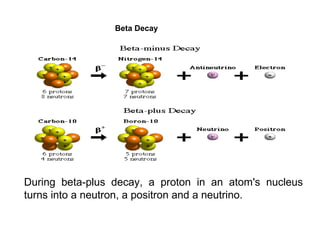

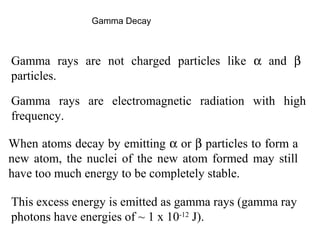

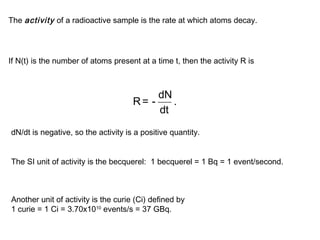

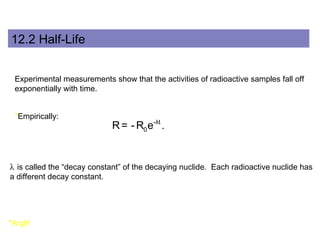

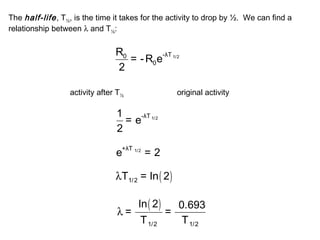

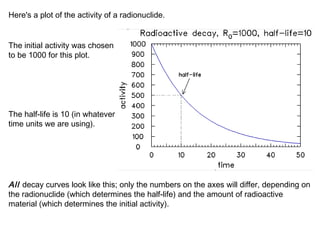

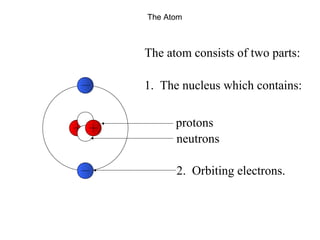

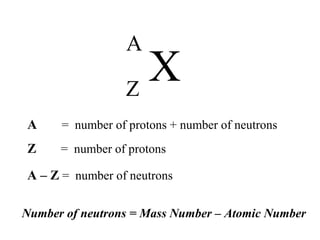

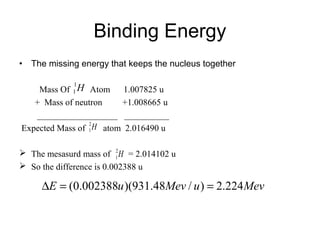

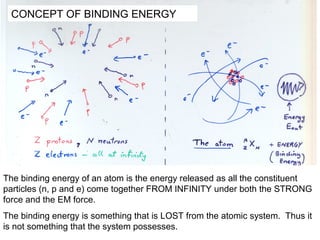

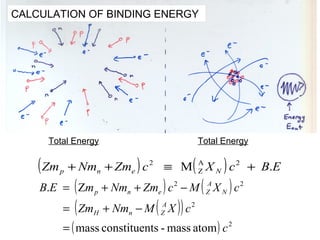

This document provides an overview of basic nuclear physics concepts. It discusses the structure of atoms including protons, neutrons, and electrons. It defines terms like atomic number, mass number, and isotopes. It explains concepts such as binding energy, radioactive decay modes (alpha, beta, gamma), activity, and half-life. Radioactive decay is described as the process by which unstable atoms emit particles or radiation to become more stable. Common decay types and their products are outlined.

![SINGLE NEUTRON SEPARATION ENERGY

The same method can be used to easily compute the “Single Neutron

Separation Energy” – which is the energy required to “pull” a neutron out of the

nucleus.

( ) ( )

[ ( ) ( )] 2

S + M X c º M

X c +

m c

S X m X c

1

1

2 2

1

2 1

M M

N

A

N n Z

A

n Z

N n

A

N Z

A

n Z

= + -

-

-

-

-

Note we don’t have to measure Sn directly.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/05nuclearbindingenergy-141117142649-conversion-gate01/85/nuclear-binding-energy-9-320.jpg)

![SINGLE PROTON SEPARATION ENERGY

The same clever strategy applies to finding the “Single Proton Separation

Energy” Sp. But note here there is a difference – we must be careful in

counting electron mass.

( ) ( 1 ) 2 2 2

S M X c2 M Y c m c m c 1

N p e

A

N Z

A

+ º - + +

p Z -

[ ( -

) ( )]

-

[ ( 1 ) ( )] 2

1 2

1

S = M Y + m + m -

M

X c

Y m X c

M M

1

N

A

N H Z

A

Z

N

A

N p e Z

A

p Z

= + -

-

-

= p S [Mass of Final Products – Mass of Initial atom] c2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/05nuclearbindingenergy-141117142649-conversion-gate01/85/nuclear-binding-energy-10-320.jpg)