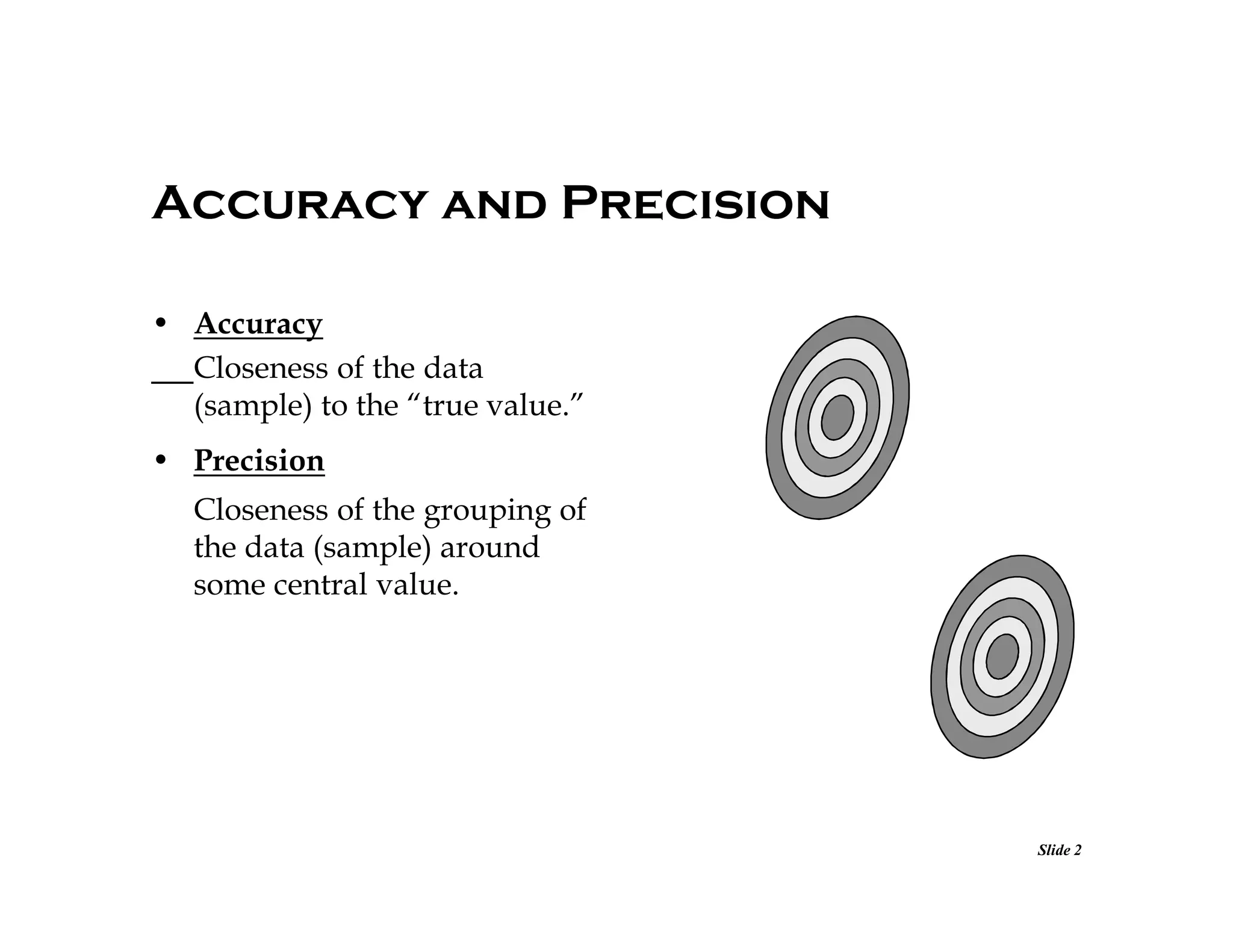

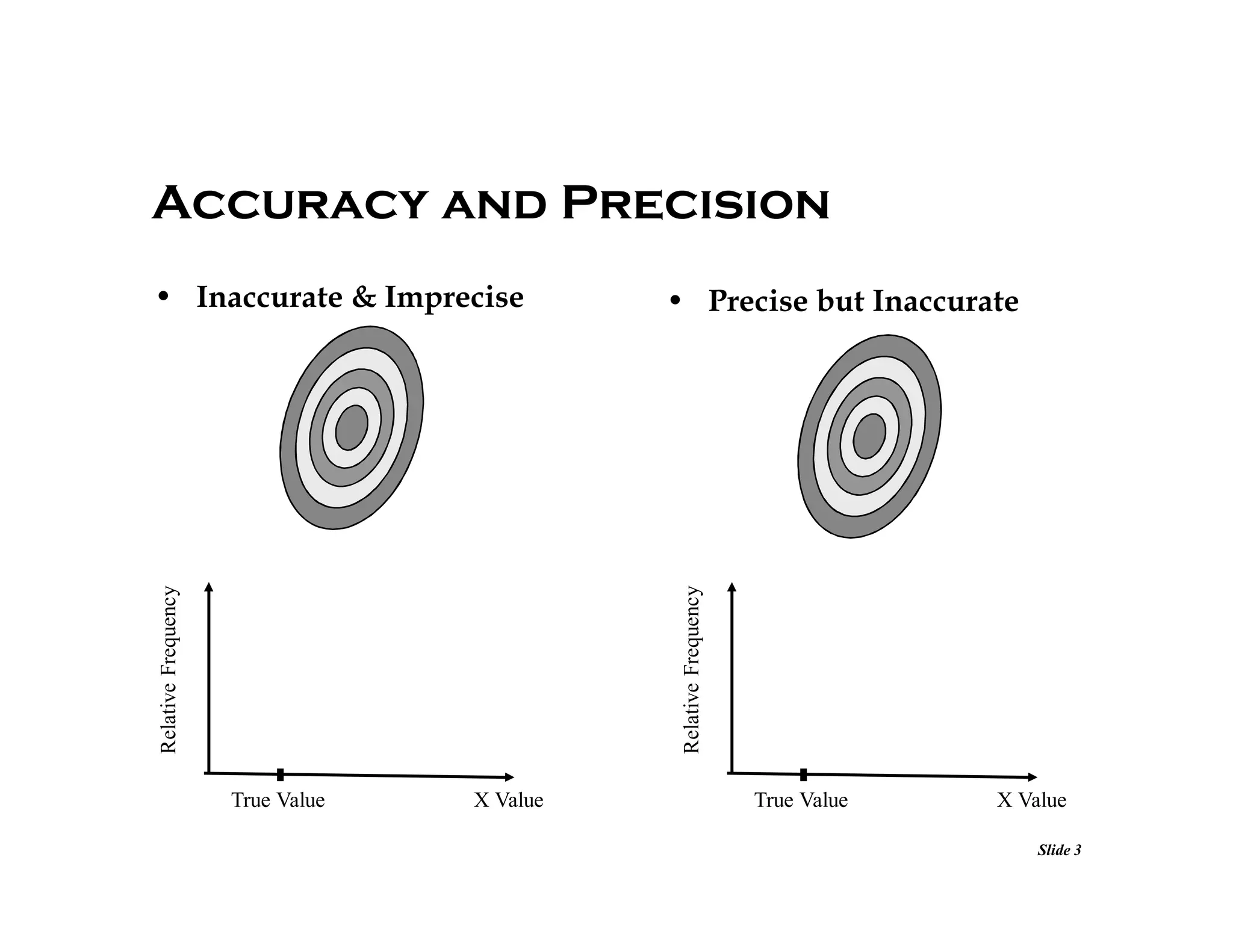

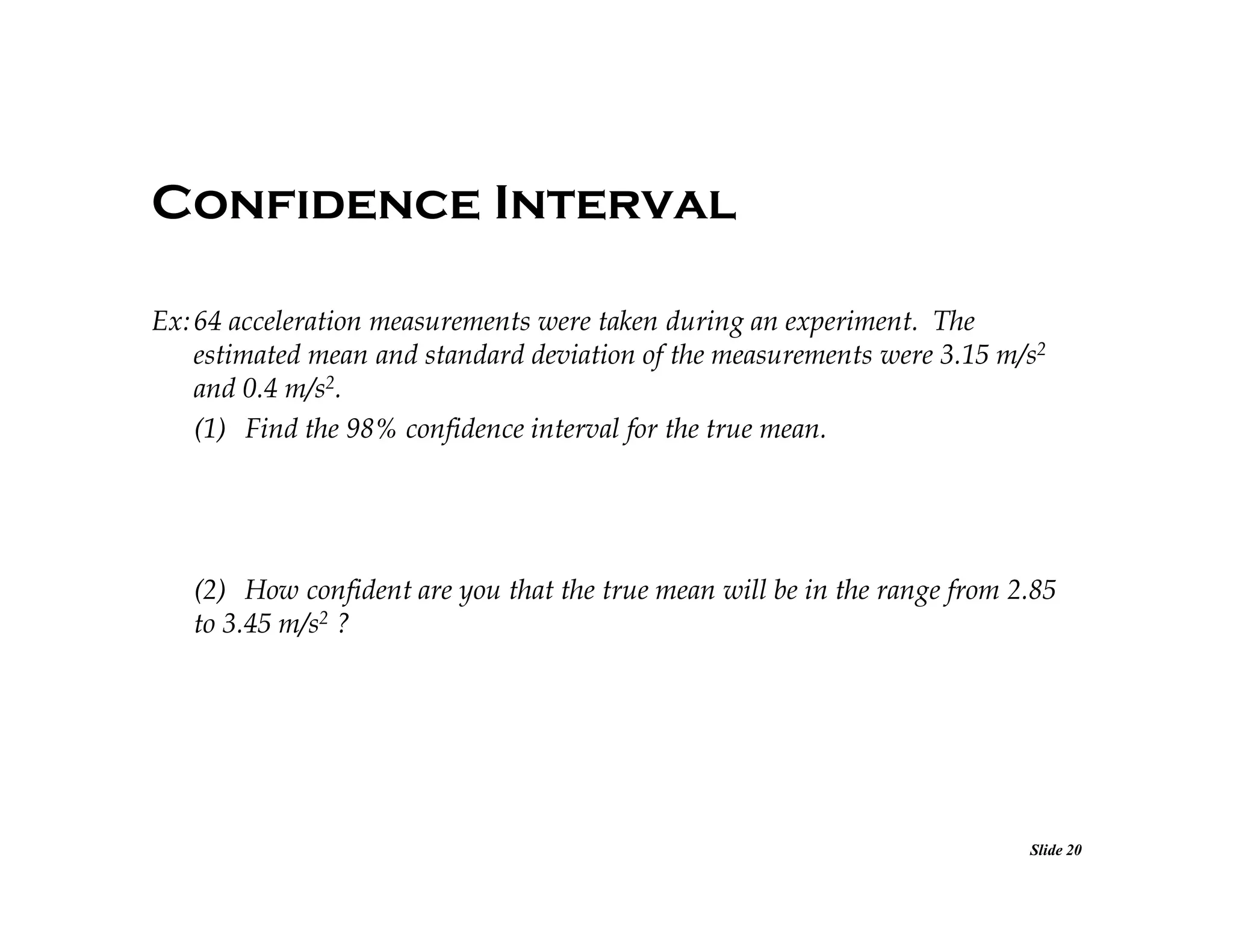

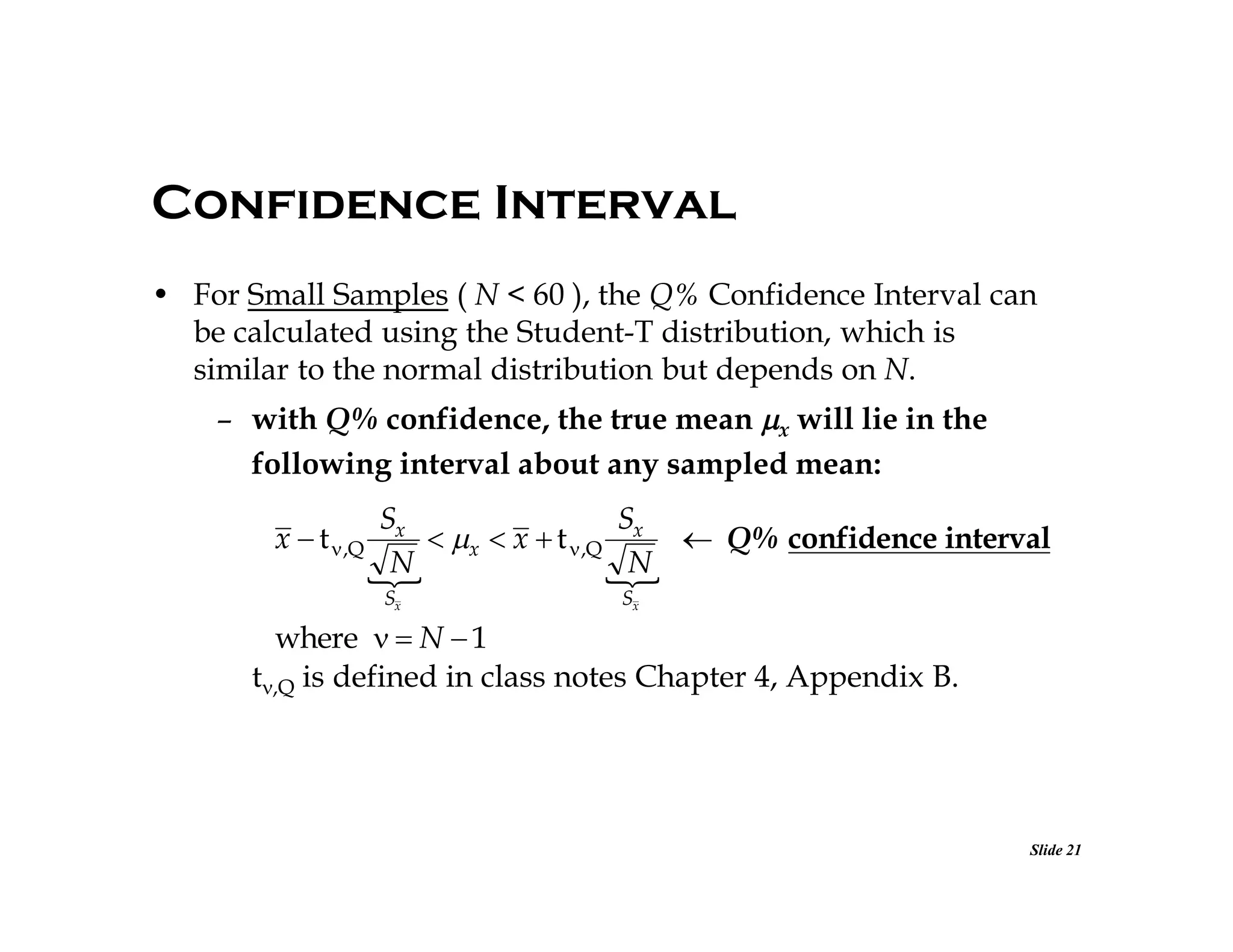

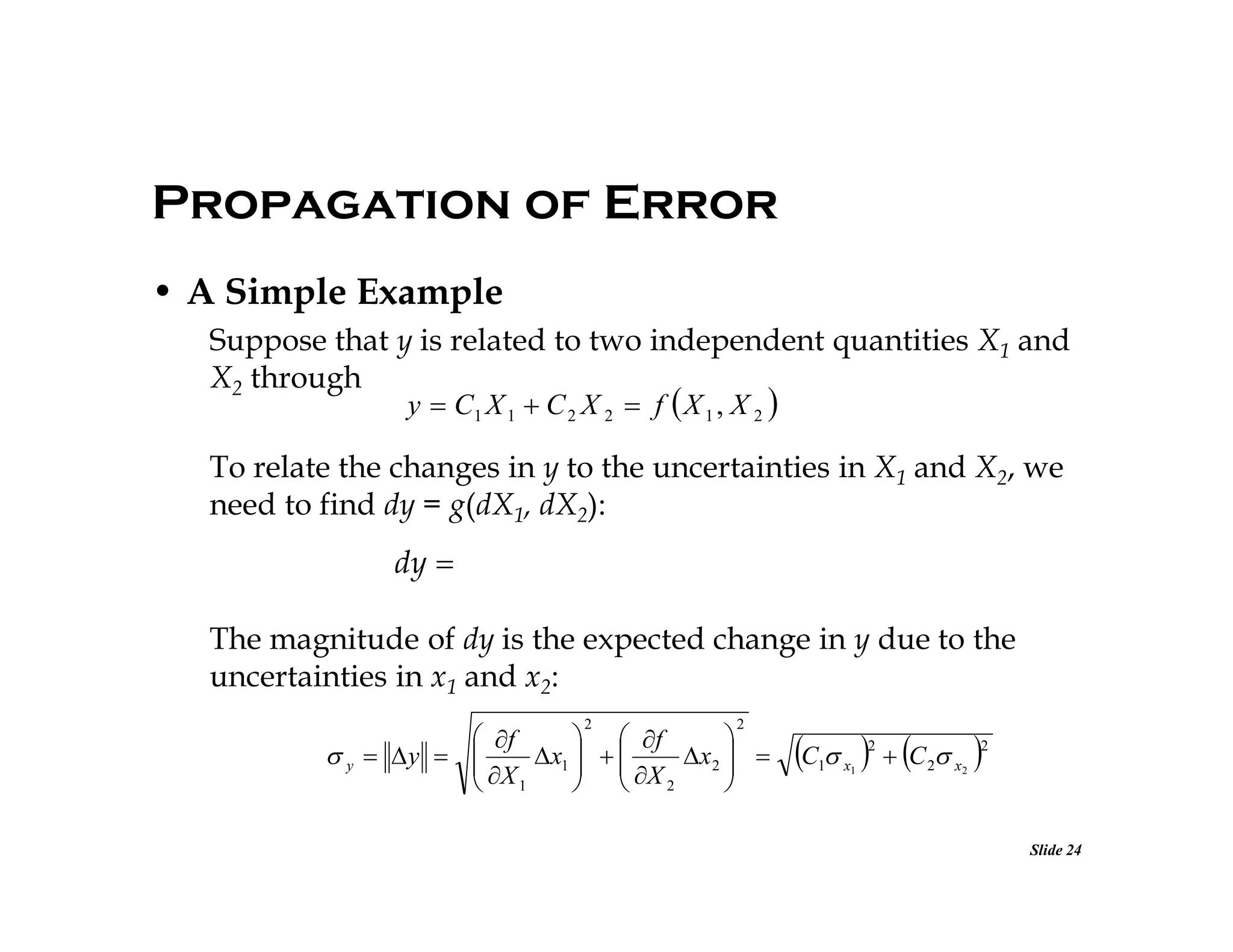

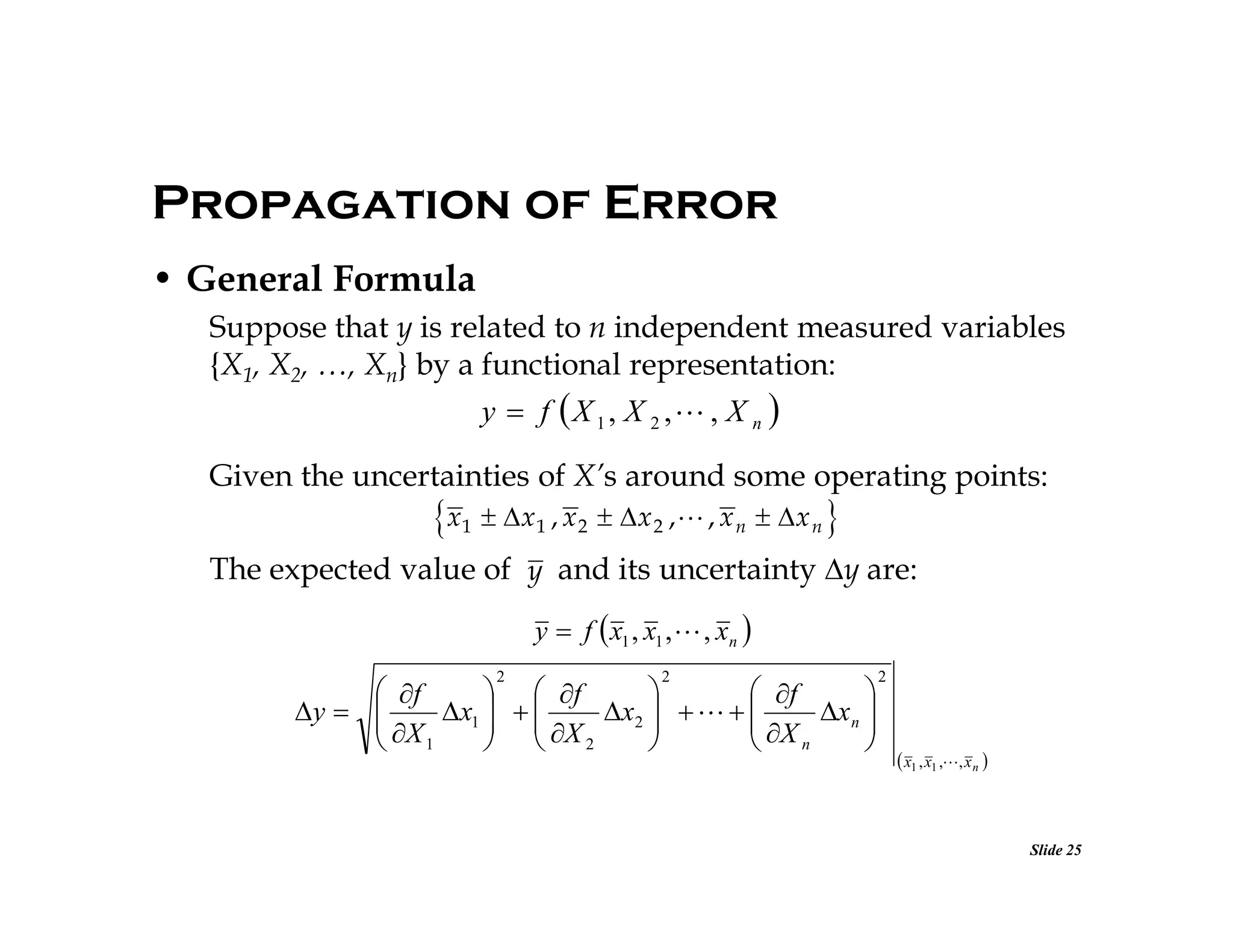

This document discusses concepts related to error analysis and statistics. It covers accuracy and precision, individual measurement uncertainty including means, variance, standard deviation and confidence intervals. It also discusses uncertainty when calculating quantities from multiple measurements using error propagation. Additionally, it discusses least squares fitting of data. Key points include how to quantify accuracy and precision, characterize the distribution of data, calculate uncertainty intervals, and propagate errors through calculations involving multiple measured variables.

![Probability Distribution (Population Based)

• Probability Density

Function (pdf) (p(x))

– Describes the probability

distribution of all possible

measures of x.

– Limiting case of the relative

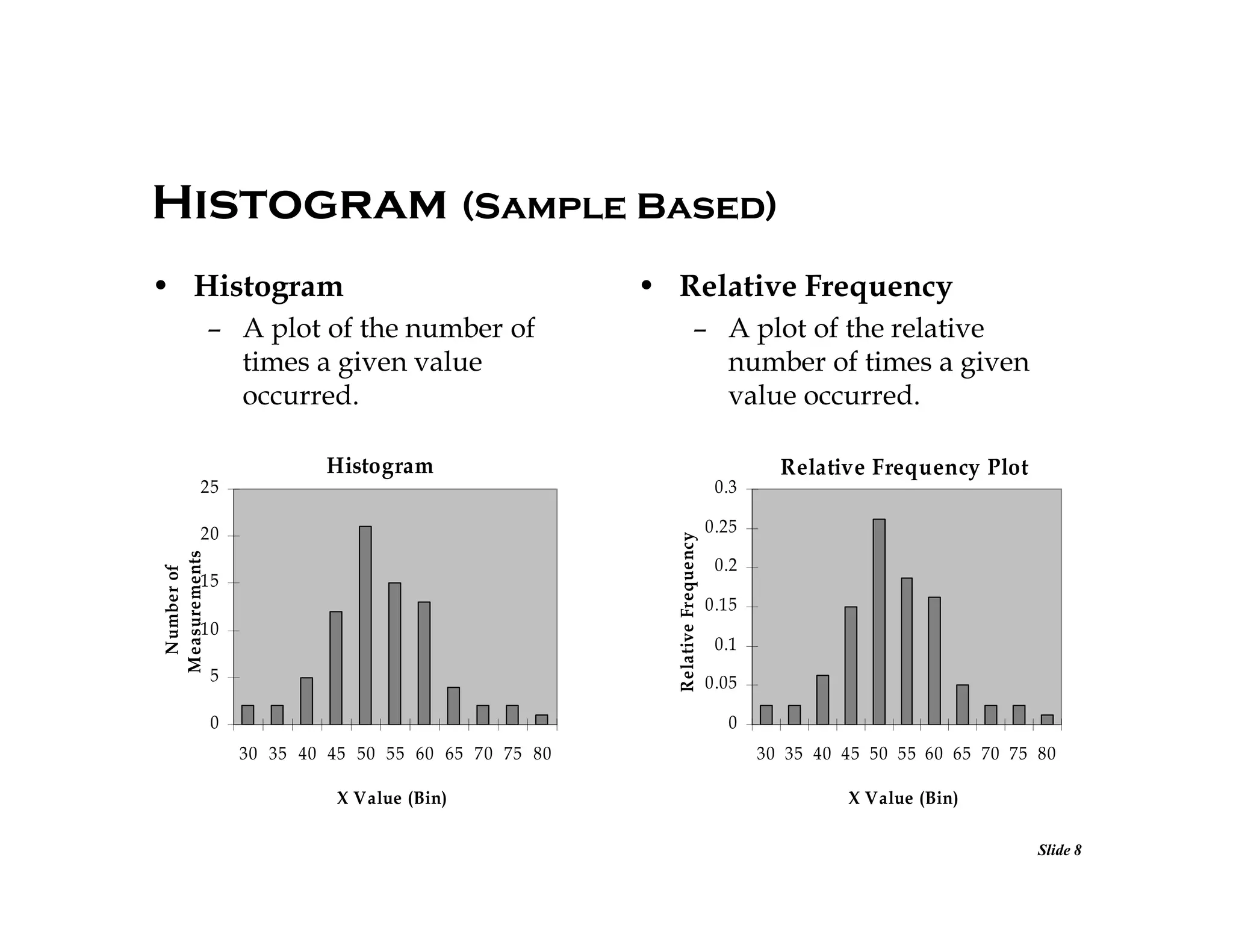

frequency.

Probability Density Function

Probability per unit

change in x

0.3

• Probability Distribution

Function (P(x))

P x P[ X x]

X x

Probability that

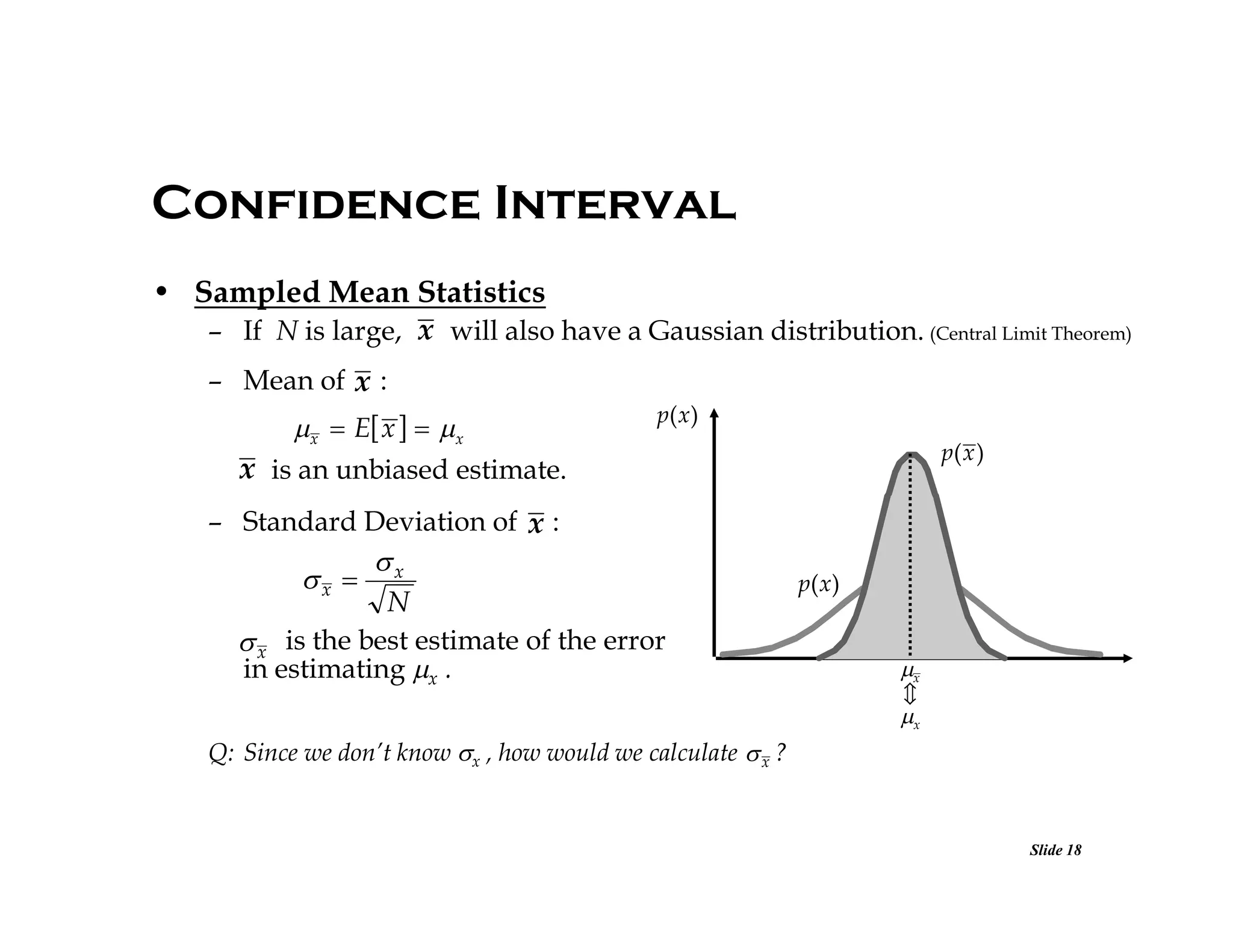

– Probability Distribution

Function is the integral of

the pdf, i.e.

x

P x p x dx

0.25

Q: Plot the probability distribution function

vs x.

Q: What is the maximum value of P(x)?

0.2

0.15

0.1

0.05

0

30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80

x Value (Bin)

Slide 9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erroranalysis-statistics-140129181324-phpapp01/75/Error-analysis-statistics-9-2048.jpg)

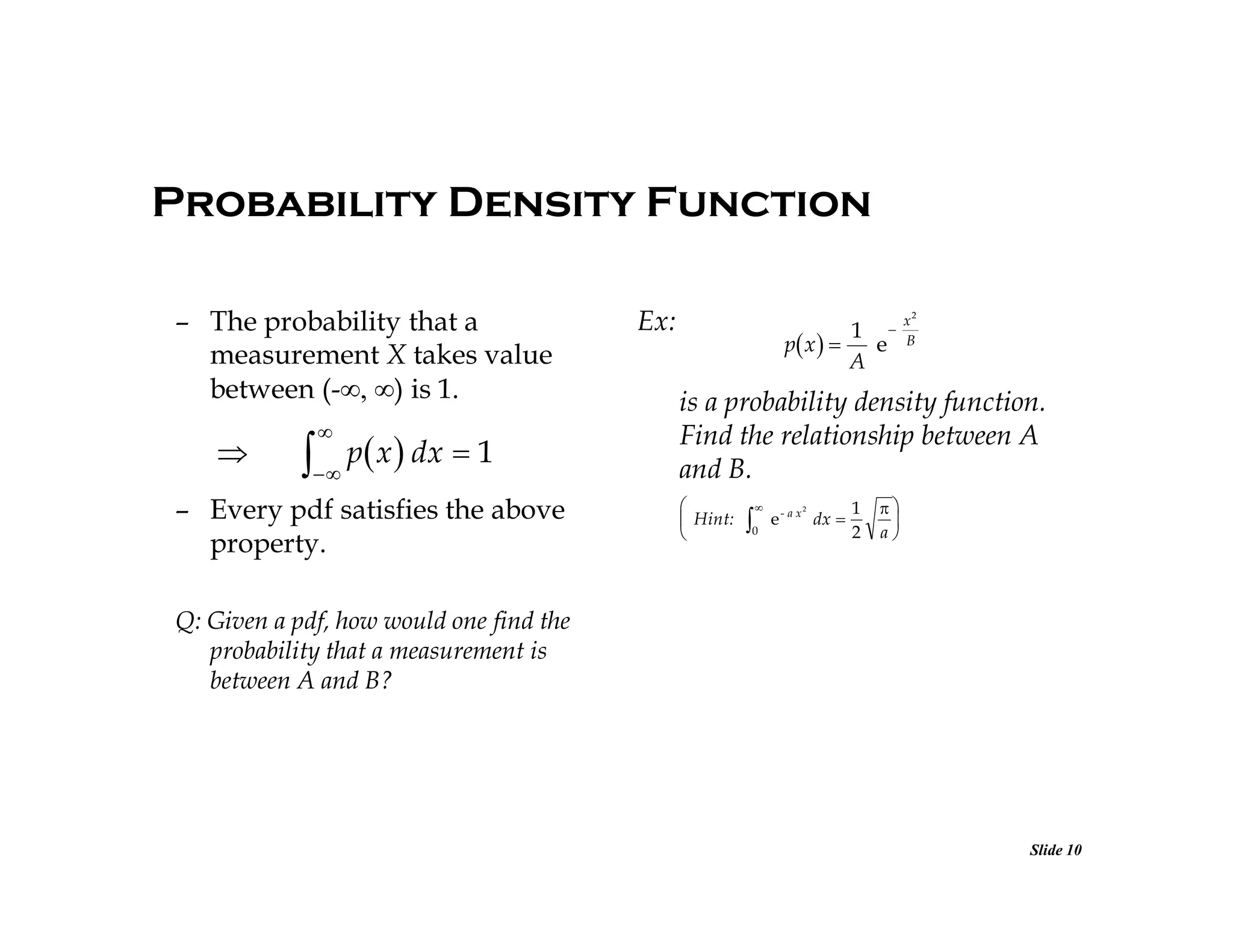

![Common Statistical Distributions

Ex: A voltage measurement has a Gaussian

distribution with mean 3.4 [V] and a

standard deviation of 0.4 [V]. Using

Chapter 4, Appendix A, calculate the

probability that a measurement is

between:

(a) [2.98, 3.82] [V]

Ex: The quantization error of an ADC has

a uniform distribution in the

quantization interval Q. What is the

probability that the actual input voltage

is within Q/8 of the estimated input

voltage?

(b) [2.4, 4.02] [V]

Slide 13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erroranalysis-statistics-140129181324-phpapp01/75/Error-analysis-statistics-13-2048.jpg)

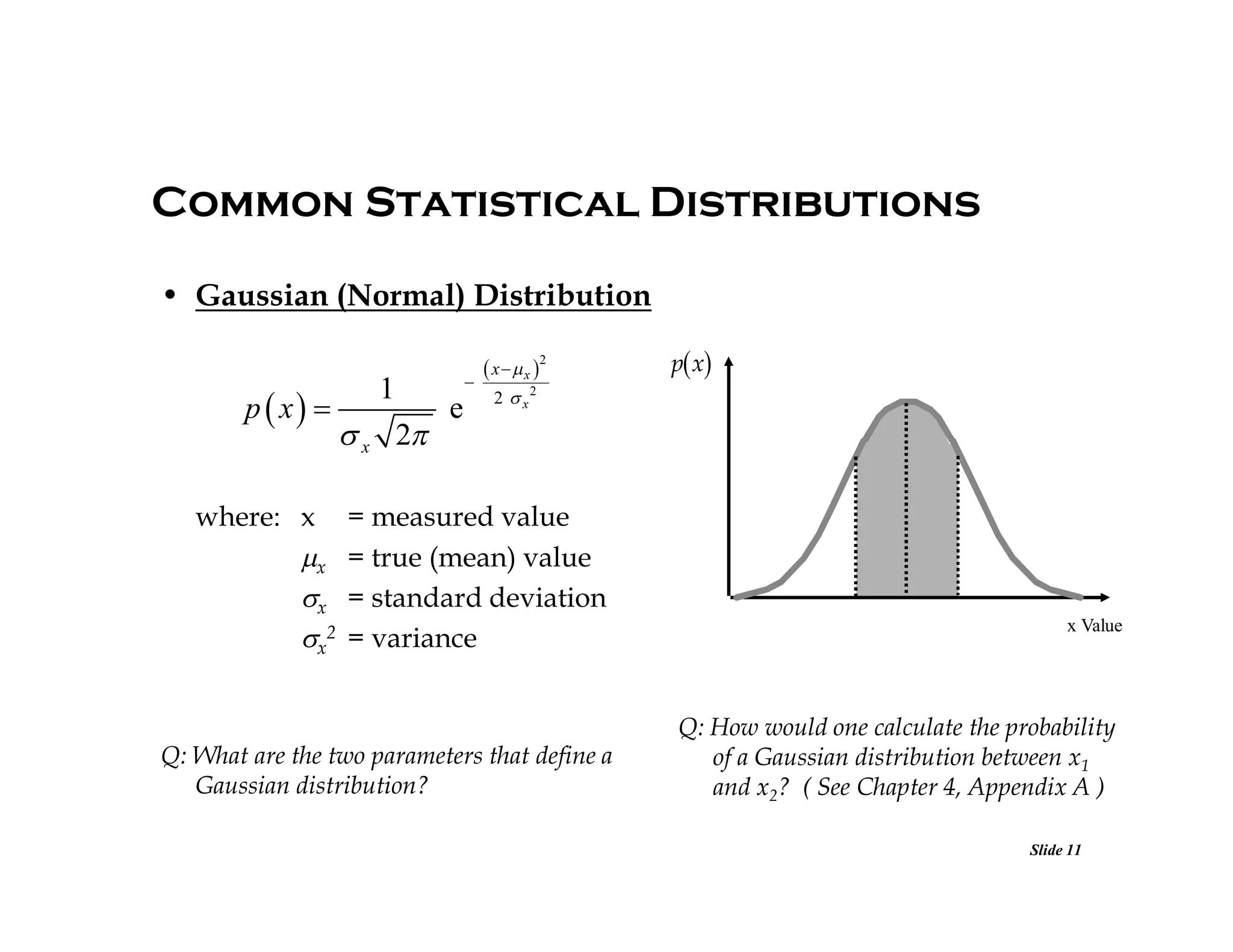

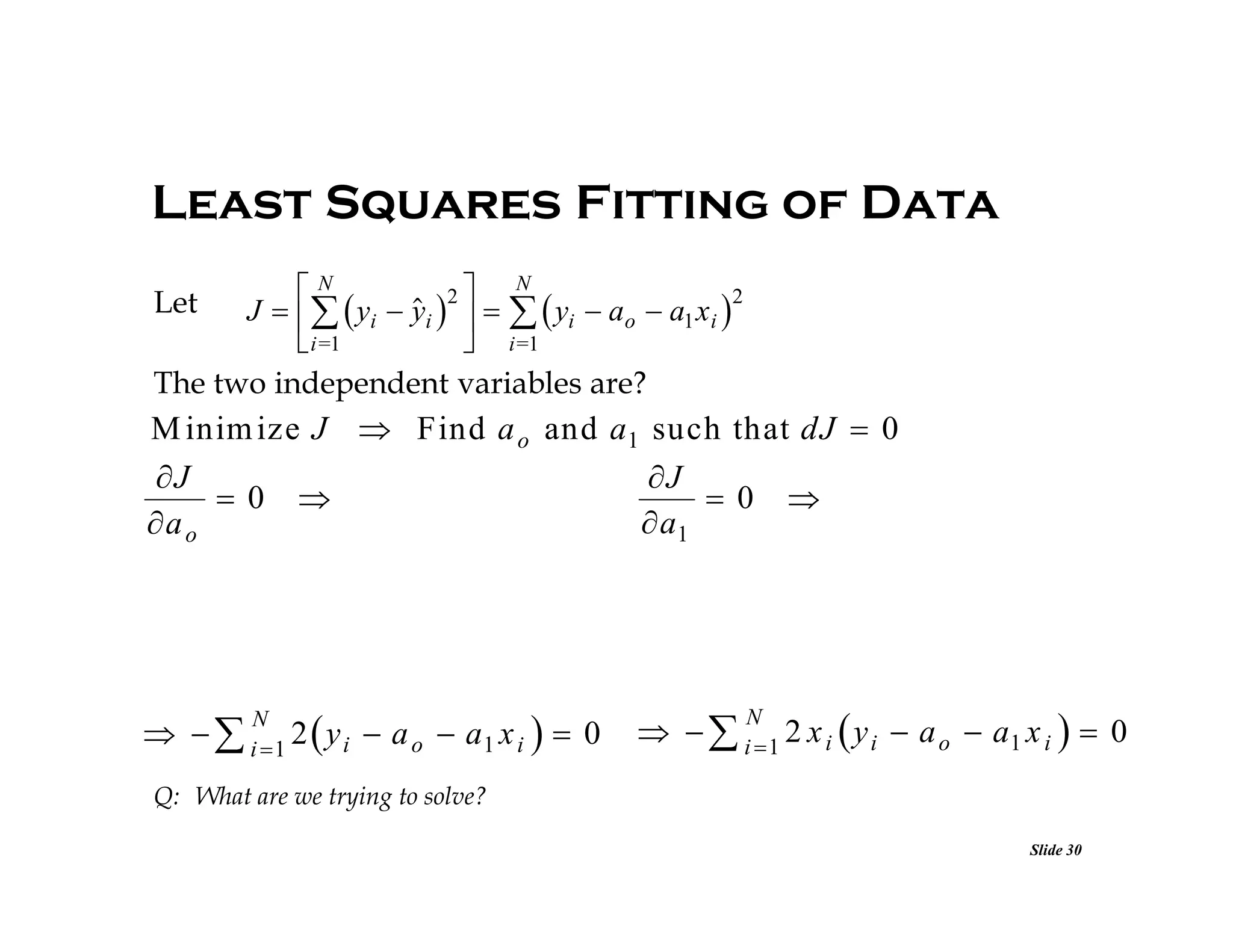

![Propagation of Error

•Proof:

Assume that the variability in measurement y is caused

by k independent zero-mean error sources: e1, e2, . . . , ek.

Then, (y - ytrue)2 = (e1 + e2 + . . . + ek)2

= e12 + e22 + . . . + ek2 + 2e1e2 + 2e1e3 + . . .

E[(y - ytrue)2] = E[e12 + e22 + . . . + ek2 + 2e1e2 + 2e1e3 + . . .]

= E[e12 + e22 + . . . + ek2]

y

E e1 2 E e2 2 E e k 2 1 2 2 2 k 2

Slide 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erroranalysis-statistics-140129181324-phpapp01/75/Error-analysis-statistics-26-2048.jpg)

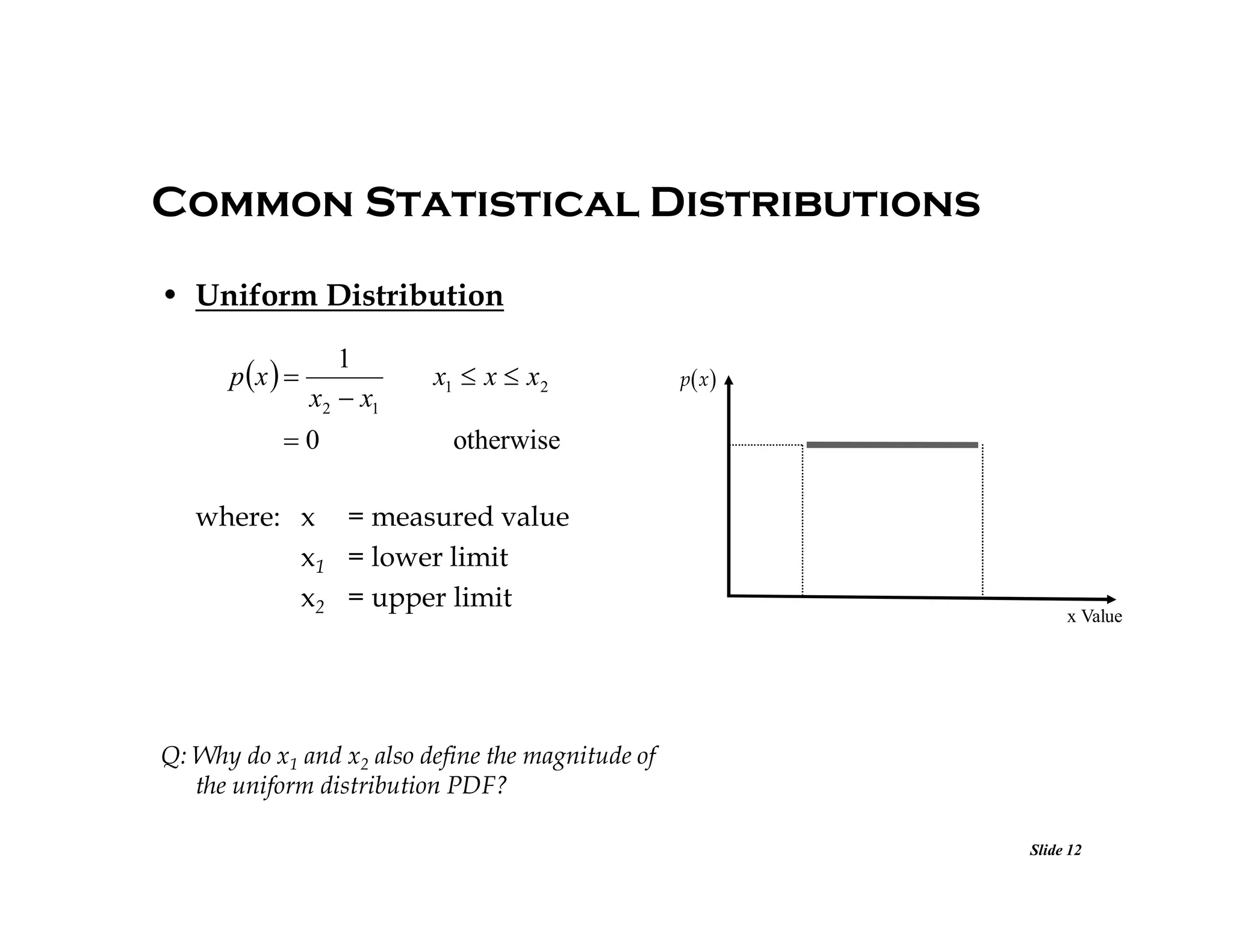

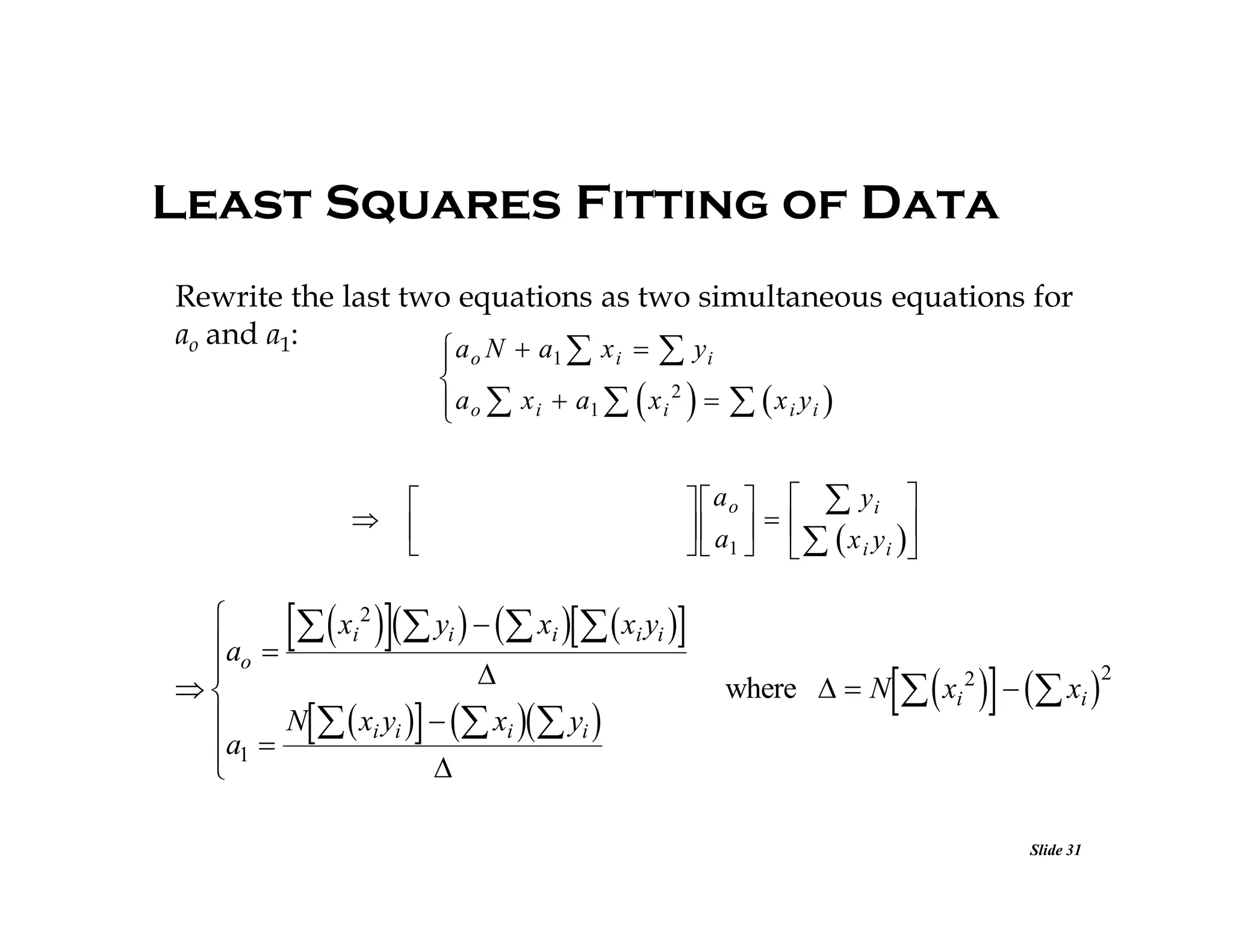

![• Best Linear Fit

–How do we characterize “BEST”?

Fit a linear model (relation)

Output Y

Least Squares Fitting of Data

best linear

fit yest

yi ao a1 xi

to N pairs of [xi, yi] measurements.

Given xi, the error between the

estimated output y i and the measured

output yi is:

ni yi yi

measured

output yi

Input X

The “BEST” fit is the model that

N 2

N

2

min ni min yi yi

minimizes the sum of the ___________

i=1

i=1

of the error

Least Square Error

Slide 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erroranalysis-statistics-140129181324-phpapp01/75/Error-analysis-statistics-29-2048.jpg)

![Least Squares Fitting of Data

• Summary: Given N pairs of input/output measurements [xi, yi],

the best linear Least Squares model from input xi to output yi is:

yi ao a1 xi

x y x x y

2

where

ao

a1

i

i

i

i i

N x i yi x i yi

and N

x i 2 xi

• The process of minimizing squared error can be used for fitting

nonlinear models and many engineering applications.

• Same result can also be derived from a probability distribution

point of view (see Course Notes, Ch. 4 - Maximum Likelihood Estimation ).

Q: Given a theoretical model y = ao + a2 x2 , what are the Least Squares estimates for ao & a2?

Slide 32

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erroranalysis-statistics-140129181324-phpapp01/75/Error-analysis-statistics-32-2048.jpg)