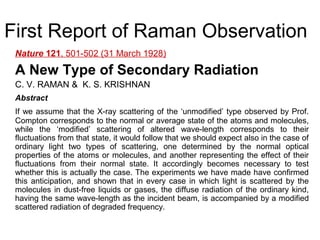

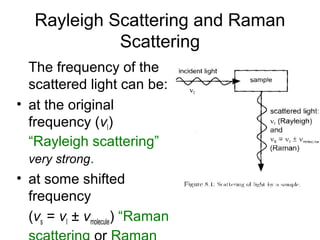

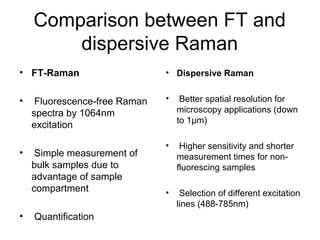

This document provides an overview of Raman spectroscopy. It begins by defining spectroscopy as the study of how atoms and molecules interact with light. It then describes Raman scattering, which was discovered by C.V. Raman in 1928 and involves a change in frequency of scattered light that depends on the chemical structure of molecules. The rest of the document discusses key aspects of Raman spectroscopy such as Stokes and anti-Stokes scattering, the relationship between Raman and infrared spectroscopy, and applications of Raman spectroscopy such as molecular identification and quantification.