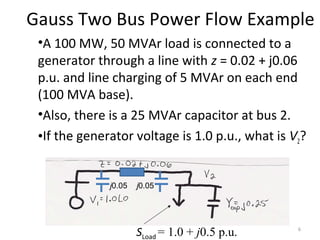

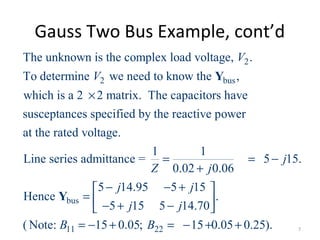

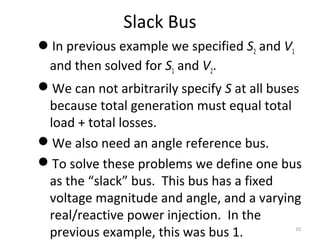

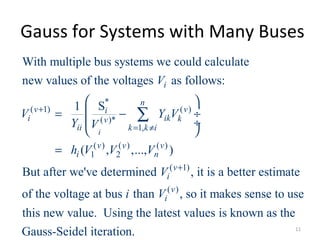

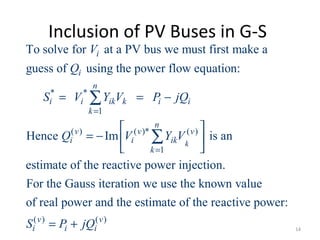

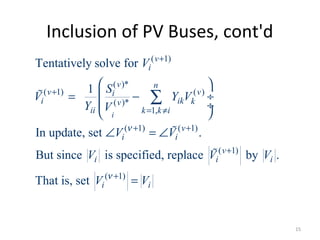

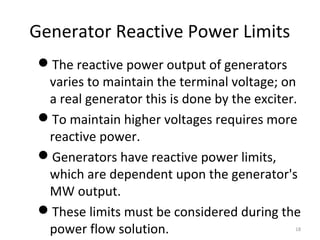

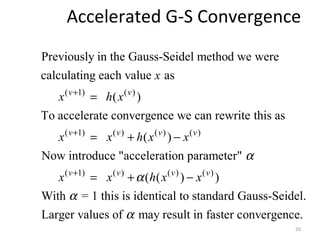

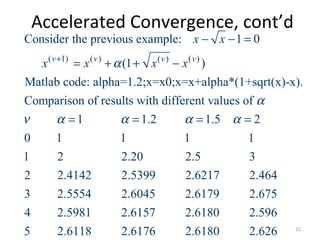

This document discusses a lecture on power flow analysis in a power systems engineering course. It provides announcements about homework assignments and an upcoming midterm exam. It also discusses examples of the Gauss two bus power flow method and the inclusion of PV generator buses in the Gauss-Seidel iteration method. Key concepts covered include slack buses, generator reactive power limits, and methods to accelerate Gauss-Seidel convergence.

![Two Bus PV Example, cont'd

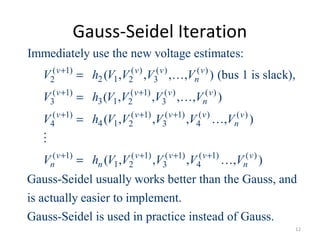

( ) ( )* ( )

22 2

1

( ) ( )* ( ) ( )*

21 221 2 2 2

( )* ( )*

( 1) ( ) ( )2 2

2 212 1( )* ( )*

22 221, 22 2

(0)

2

( ) ( 1) ( 1)

2 2 2

Im ,

Im[ ]

1 1

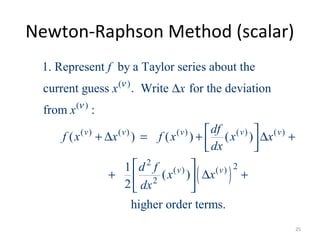

Guess 1.05 0

0 0 0.457

k

n

v v

k

k

n

k k

k k

v v v

Q V Y V

Y V V Y V V

S S

V Y V Y V

Y YV V

V

v S V V

j

ν

ν ν ν ν

ν ν

ν ν ν

ν ν

=

+

= ≠

+ +

= −

= − +

= − = − ÷ ÷

= ∠ °

+

∑

∑%

%

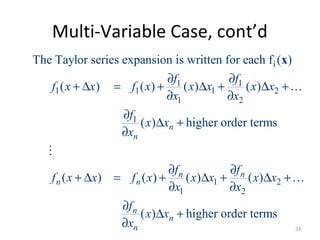

1.045 0.83 1.050 0.83

1 0 0.535 1.049 0.93 1.050 0.93

2 0 0.545 1.050 0.96 1.050 0.96

j

j

∠ − ° ∠ − °

+ ∠ − ° ∠ − °

+ ∠ − ° ∠ − ° 17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture11-160904123658/85/Lecture-11-17-320.jpg)

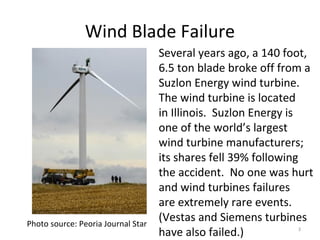

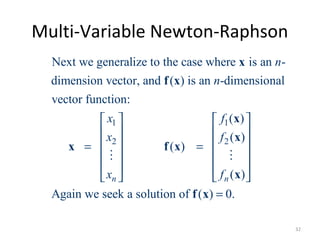

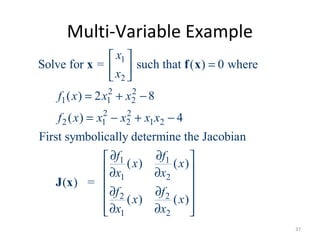

![Multi-variable Example, cont’d

1 2

1 2 1 2

1

1 1 2 1

2 1 2 1 2 2

4 2

( ) =

2 2

4 2 ( )

Then

2 2 ( )

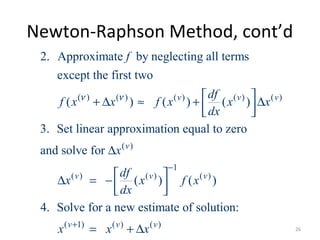

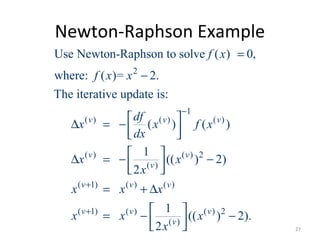

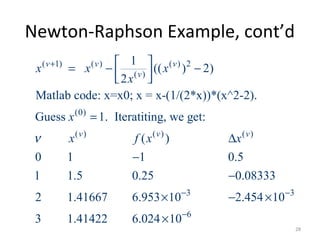

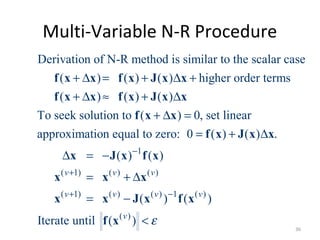

Matlab code: x1=x10; x2=x20;

f1=2*x1^2+x2^2-8;

f2=x1^2-x2^2+x1*x2-4;

J = [4*x1 2*x2; 2*x1+x2 x1-2*x2];

[x1;x2] =

x x

x x x x

x x x f

x x x x x f

−

+ −

∆

= − ∆ + −

J x

x

x

[x1;x2]-inv(J)*[f1;f2].

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture11-160904123658/85/Lecture-11-38-320.jpg)