The document provides an overview of phonetics, focusing on the study of the physical aspects of speech sounds. It distinguishes between the American and European terminologies in linguistics and describes the articulatory, acoustic, and auditory aspects of phonetics. It also classifies speech sounds into consonants and vowels based on their production characteristics, detailing their places and manners of articulation.

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

36 | Introduction to Linguistics

(IPA) is then used. Phonetic characters refer to the actual

utterance of a sound. In phonetic writing, the symbols for these

sounds are put within brackets, such as: [θ].

Back to phonetics, we stated above that there are three

different physical aspects of a sound. These are the articulatory

aspect of the speaker, the acoustic aspect of the channel, and

the auditory aspect of the hearer.

Articulatory phonetics researches where and how

sounds are originated and thus carries out

physiological studies of the respiratory tract, trying to

locate precisely at which location and in which manner

a sound is produced.

Acoustic phonetics examines the length, frequency and

pitch of sounds. Special instruments are required to

measure and analyze the sounds while they travel via

the channel.

Auditory phonetics studies what happens inside the ear

and brain when sounds are finally received. It also

interested in our ability to identify and differentiate

sounds.

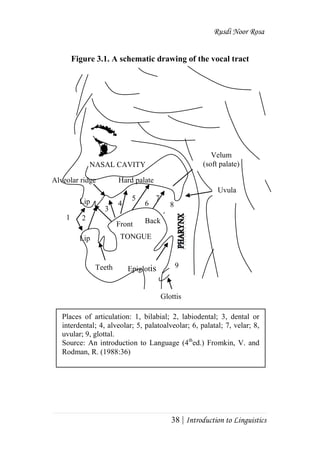

3.1 How speech is produced

Everyday, we always speak to other people without

any consciousness why we are able to produce the sound of

utterances. How and where sounds are produced within our

vocal tracts determines the acoustic properties of those sounds.

Gleason and Ratner (1998:113) noted three major systems for

speech production: (1) the vocal tract, (2) the larynx, and (3)

the subglottal system.

Let us first identify the body parts that are involved in

speech production. Figure 3.1 is a diagram of most of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-4-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

44 | Introduction to Linguistics

Bilabials are consonants that are articulated by

pressing the lips, like [m].

Labiodentals are consonants articulated by bringing

the lower lip to the upper teeth, like [f]. As the lower

lip experiences some movement, it is categorized as

active articulator and the upper teeth are passive

because they do not show any movement.

Nevertheless, the name is taken from the combination

of the two articulators.

Interdentals or Dentals are the sounds at the

beginning of ―thin‖ and ―then‖, in IPA: [θ] and [ð]. In

order to articulate these, the tongue must be pressed

between the teeth.

Alveolars are consonants articulated by raising the tip

of the tongue to thealveolar ridge (a linguistic term for

teeth ridge), like [d]. The name of the group, alveolar,

is taken from the passive articulator, alveolar ridge.

Post-alveolars are consonants articulated by raising

the tip of the tongue to the space between alveolar

ridge and hard palate. They are neither alveolar as the

tongue position is not in the area of alveolar ridge nor

palatal as the tongue fails to reach the exact area of

hard palate. Sounds [ʧ], [ʤ], and [r] are examples of

post-alveolars.

Palatals as in the middle of the word ―wash‖ are

produced by the contact of the front part of the tongue

with the hard palate just behind the alveolar ridge. An

example is [ʃ].

Velars are sounds which are articulated by raising the

back of the tongue to the soft palate, linguistically

known as velum. An example is [g].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-12-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

46 | Introduction to Linguistics

the air is released in rush, the sounds which are produced

through this way are called stops, also known as plossives, e.g.

[t]. But, when the blockage is kept and the air is released

through the nose, we call the resulting consonant is a nasal, as

in [m].

When the articulators are closed together, but without

complete closure, the air passage is forced to go through the

narrow space of articulators. This action results in friction, a

sound turbulance. As the sound produced is followed by the

presence of friction, the sound is named fricative. Other

sounds that are followed by friction are affricates. However,

they are different from fricatives in the way that the sounds, in

the beginning of production, must have a complete closure of

articulators. This means that the air passage is blocked before

it is released through narrow space of articulators, such as in

[ʧ]. These sounds are also known as a result of fricative-stop

combination.

The other two types – liquids and glides – let the air

passage go freely through oral cavity. However, the exact

manner of articulation is obviously different. Liquids, also

known as laterals, block force the air passage to go through

each side of the oral cavity. Some part of the tongue that is

pressed onto the alveolar ridege blocks the the middle part of

the oral cavity. Meanwhile, liquids, also known as semi-

vowels, shape the articulators wide apart and let the air flow

out freely. It seems that they resemble vowels in the manner of

―free release without blocking‖; however, the involvement of

articulators, such as lips and front tongue make themselves

consonants.

The classification of consonants based on manner of

articulation can be shown in the following table.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-14-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

54 | Introduction to Linguistics

Crane, L. Ben et al. 1981.An Introduction to Linguistics.

Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Fromkin, V.A. and R. Rodman. 1988. An Introduction to

Language. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Gleason, J.B., and N.B. Ratner. 1998. Psycholinguistics. New

York: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Lass, R. 1994. Phonology: An Introduction to Basic Concepts.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mc Mahon, A. 2002. An Introduction to English Phonology.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

3.4.2 Questions for Discussions

1. How do you define phonetics?

2. What are the differences between consonant and vowel?

3. How are fricative consonants produced? Give examples.

4. List classifications of consonants based on place of

articulation. Elaborate your answers by providing

examples.

5. Complete the sentences by choosing one of the following

features: [+continuant], [+sonorant], [+anterior],

[-coronal], [-consonantal].

a. The labiodental, interdental, and alveolar are

……………..](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-22-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

58 | Introduction to Linguistics

Compare two words which differ only by one sound, e.g.,

―pin‖ and ―bin‖. By replacing the beginning consonants, the

meaning of the word changes. We call such pairs minimal

pairs. Minimal pair is two words that (i) have the same number

of segments, (ii) have only one different segment, and (iii)

have different meaning. The test we just performed to locate

the phonemes is called Commutation Test. The phonemes

thereby discerned are then put within slashes, such as /p/, /b/,

for phonological transcription. These are, of course, ideal units

of the sound system of a language. They should not be

confused with the sounds of actual utterances examined by

phonetics. Phonetics tries to differentiate among the sounds

with the highest possible degree of accuracy. It does so without

regard for the influence of a sound may have on the meaning

of an utterance.

However, not all sounds of a language are necessarily

distinctive sounds. Let‘s take the Indonesian word ―kemana

(where)‖, for example, which is pronounced either [kәmᴧnᴧ]

or [kæmᴧnᴧ]. Although there are obviously different sounds in

the pair, the meaning does not change. Thus, /ә/ and /æ/ are not

phonemes in the Indonesian language. We call this

phenomenon free variation. The two sounds can be referred to

as allophones. These sounds are merely variations in

pronunciation of the same phoneme and do not change the

meaning of the word. Nevertheless, these two different sounds,

―/ә/ and /æ/‖, may act as phonemes in another language such as

English. Let‘s take the pair of words ―were‖ and ―where‖ as

the example. These words are respectively pronounced [wә(r)]

and [wæ(r)]. Different sounds in this pair reslt in different

meaning which; therefore, belong to phonemes. By using these](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-26-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

59 | Introduction to Linguistics

two examples, a conclusion may be drawn: phonemes in one

language may not be phonemes in another language.

Free variation can also be found in various dialects of

the same language. In this case, the different pronunciations of

words throughout a country do not change the meaning of

those words. Compare the English and American

pronunciations of ―dance‖: [dɑ:ns] versus [dæns]. Although

there are different sounds in the pair, the meaning does not

change. Thus, /ɑ:/ and /æ/ are not phonemes in this case.

Another example of sounds which are not phonemes

are those which occur in complementary distribution. A

phoneme is called to have complementary distribution when it

occupies different position in words. This means that where

one sound of the pair occurs, the other cannot. An example for

complementary distribution are the aspirated, unaspirated, and

unreleased sounds of /p/. Aspirated sounds are those which

contain audible puff of the air. When the voiceless stops (/p/,

/t/, and /k/) begin the word and are followed by stressed vowel,

there is likely to be an audible puff of the air following the

release. The initial consonant as in ―pill‖ is aspirated. The

initial consonant in ―pacific‖ is unaspirated. The final

consonant as in ―sheep‖ is unreleased. The respective

transcriptions would be [ph

il], [pæsi:fik], and [ʃi:p-

] where [h

]

indicates aspiration and [-

] indicates unreleased. Aspirated [ph

],

as can be seen in this example, occurs before the stressed

vowel; [p-

] takes place in the final position of the word. [ph

],

[p], and [p-

] are only allophones of the same phoneme /p/.

Another example of the occurence of complementary

distribution is in the pronunciation of /æ/ in ―back‖ and ―bag‖.

Everybody will find it difficult to identify the difference in

vowel length. As it is known, English has a very general](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-27-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

60 | Introduction to Linguistics

pattern of lengthening vowels before voiced consonants. That

is, the allophone of a vowel phoneme before a voiced

consonant will be produced longer than the allophone of the

same vowel phoneme before a voiceless consonant. We can

represent the pattern of occurrence (distribution) of these two

allophones of the phoneme /æ/ as the following phonological

rule: When the phoneme /æ/ occurs before a voiceless

consonant, it is pronounced as its allophone [æ]; when it

occurs before a voicedconsonant it is pronounced as its

allophone [æ:]. It means that /æ/ is pronounced longer only

before a voiced consonant, but in another environment, it is

not.

Nasalized vowels can also contribute to the occurence

of complementary distribution. Note that the phoneme /u:/ in

―tool‖ and ―tone‖ is pronounced differently – even though,

sometimes, we are anware of this difference. /u:/ is pronounced

[ũ:] when it is followed by nasal sound /n/, but this cannot

occur before other consonants. In fact, the rule is much more

general than this, because it is applied to all vowels and all

nasals. Therefore, a general statement can be issued: In

English, all vowels are nasalized when they occur before nasal

consonants. This generalization should be made because one

of the objectives in studying a language is to be able to

describe the sound patterns, i.e., to be able to specify, in as the

most general terms as possible, the phonetic environments in

which each allophone occurs.

As mentioned earlier, we can use a minimal pair to

determine whether a sound is a phoneme, an allophone, or a

complementary distribution. How a minimal pair works to

classify such variations of sounds is illstrated in the figure 4.1.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-28-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

64 | Introduction to Linguistics

Consider the meaning of each sentence: (a) I ever gave

him another thing, but not the book; (b) I ever gave him a

book, but not that one; (c) I ever gave that book to someone

else; but not to him; and (d) Someone has ever given him that

book, but I never did.

4.2.3 Intonation

Intonation is the rise or the fall of voice produced by

someone while speaking. In English, intonation is included as

a phoneme since different intonation used by the speaker in

delivering their message will affect the meaning of his/her

utterance. There are four kinds of intonation: rising intonation,

falling intonation, dipping intonation, and peaking intonation.

Rising intonation means the voice increases over time, and is

commonly symbolized []. It usually indicates questioning or

seeking the truth of a particular information. Falling intonation

means the voice decreases with time, and is commonly

symbolized []. It usually gives an impression of finality: no

more idea to be said. Dipping intonation means ―falls and then

rises‖ and is commonly symbolized []. It usually shows

limited agreement, response with reservation, offering choice,

uncertainty, or doubt. Peaking intonation means ―rises and

then falls‖, and is commonly symbolized []. It is used to

convey strong feelings of approval, disapproval or surprise.

The statement ―You are a doctor‖, for example, demonstrates

how the use of rising and falling intonation results in different.

(a) [Budi is a doctor]

(b) [Budi is a doctor]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-32-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

67 | Introduction to Linguistics

Third, the phonological representations used were linear

sequences of matrices of feature values. No structure

beyond the linear structure of these matrices or segments

was included; in particular, there were no syllables

included in the model. Segments – phones – were to be

represented as bundles of binary features, in a fashion

very similar in character to what had been proposed by

Jakobson (1956), much of that in collaboration with Halle.

Finally, discovering deep rule ordering was a high priority

of the theory, in the following sense. For each pair of

rules, one would attempt to determine that one and only

one ordering of the rules (that) was consistent with the

data, and one attempted to establish that a total ordering

of the rules could be established which was consistent

with each pairwise ordering empirically established. For

example, if a language has a phonological rule that

lengthens vowels before voiced consonants (which would

be written V → [+long]/ ___ [C,+voice]), and a rule that

voices intervocalic obstruents ([−sonorant] →

[+voice]/V___V), then the language must also contain a

statement as to which of those two rules applies ―before‖

the other, because the predictions of the grammar would

vary depending on this rule ordering.

The ideas mentioned above suggest the existence of a

rule that can be used to describe the phenomena taking place in

the language sound system. A rule is an operational statement

in which some linguistic entity is modified, resulting in a new

linguistic entity. Rules may add elements, remove elements, or

change elements. They are theoretical statements on the part of

the linguist, who is attempting to demonstrate that there is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-35-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

68 | Introduction to Linguistics

order in linguistic phenomena, that linguistic patterns are

systematic.

Phonological rules may add, delete, or change

phonological elements. A phonological derivation is an

operation that begins with an underlying representation and,

through the application of a set of specific rules, yields the

actual sound the speaker produces.

The representation of a phonological rule has the general

appearance:

A → B/C

The A in this rule represents that which is going to be changed

by the rule. Keep in mind that a segment in both underlying

and phonetic representation is actually a bundle of distinctive

features such as [+voice], [-anterior], [+coronal], [-nasal]; thus,

a symbol like A may represent a single phonological feature or

a set of phonological features. The arrow (→) in the rules

means ―change to‖. The B in the rule represents the new form.

The slash mark separates the rule ―A changes to B‖ from the

phonological environments or conditions under which the rule

operate, here symbolized by C. This rule may be thus read ―A

changes to B under condition C‖. However, one important

thing that should be remembered, this rule can only operate in

regular condition, as a language may have irregularities.

Conditions are normally written before or after a

horizontal line; that is

A → B/___ C

This formula shows that the segment being changed occurs

before the condition C, or

A → B/C ___

This formula shows that the segment being changed occurs

after the condition C.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-36-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

70 | Introduction to Linguistics

The braces notation indicates that a rule applies under

two or more conditions. To combine the two rules:

A → B/C ___

A → B/D ___

we write

____

which may be read: ―A changes to B following C, and A

changes to B following D‖.

These rules are used in three phonological processes,

namely segment addition, segment deletion, and segment

change rules.

4.3.1 Segment addition rules

Sometimes, features are added to phonemes when they

occur in a specific phonetic context. We have already looked at

aspirated and unaspirated occurences of stops like /p/. At the

beginning of words as in ―pill‖, /p/ is aspirated. The feature of

aspiration is hence added because /p/ is a sound at the

beginning of a word, and the following sound is a stressed

vowel. In other phonetic contexts, the feature of aspiration is

not added. The rule can be formulated as follows:

[p]→[ph

]/ #___ [V (+stress)]

The rule is, thus, read ―p is added by aspirated sound (h

) when

it is at the beginning of the word (#), and followed by a

stressed vowel‖. If distinctive feature, as the formal feature of

the rule, is used, the rule is then formulated:

D

C

BA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-38-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

71 | Introduction to Linguistics

4.3.2 Segmentdeletion rules

Phonological rules of a language may result in the

deletion of segments from a phoneme sequence. A good

example for this rule is English, where the sound /k/ is deleted

when it begins a word and precedes nasals. The rule can be

formulated as follows:

[k] →[∅]/ ___ [n]

So, the sound k in these words is deleted: know, knife, knee,

etc. If distinctive feature, as the formal feature of the rule, is

used, the rule is then formulated:

On the left-hand side of the arrow are the features needed to

uniquely specify /k/ among the consonants; that is, no other

consonants have the features [-voice], [-anterior], and [-

coronal]. The symbols ―→‖ and ―∅‖ mean that ―/k/ changes to

nothing‖, or ―/k/ is deleted‖. The word boundary ―#‖ following

the slash means the initial position of the word. The horizontal

line ―___‖ following the word boundary mark refers to the

position of k; namely, before a segment that is [n].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-39-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

72 | Introduction to Linguistics

4.3.3 Segment-change rules

Phonological rules of a language may result in the

change of segments from a phoneme sequence. In English,

there are some prefixes indicating negative meanings. One of

them is prefix in- which can appear in various sounds: [in-],

[im-], and [iŋ]. Let us take one of them; that is [im-]. Various

words such as in+balance, in+proper, in+moral show the

change of sound [n] to [m] whenever n precedes [b], [p], and

[m]. The rule can be formulated as follows:

On the left-hand side of the arrow are the features needed to

uniquely specify /n/ among the consonants; that is, no other

consonants has the features [+nasal], [+anterior], and

[+coronal]. The symbol ―→‖ means ―change to‖. On the right-

side of the arrow is the result of sound change which has the

features [+nasal], [+anterior], but [-coronal]. These features

specify /m/ among the consonants. The horizontal line ―___‖

following the slash mark refers to the position of /n/; namely,

before a segment that is [+anterior], [-coronal], and

[+consonantal] that specify b, p, and m.

The variety of phonological conditions, the ones

coming after the slash, is determined by whether the conditions

have already specified the use of the rule. Let‘s take the word

―desire‘ as an example. The letter ―s‖ in that word is

pronounced /ʒ/ as it is situated between two vowels. Then, we

may write the rule:

lconsonanta

coronal

anterior

coronal

anterior

nasal

coronal

anterior

nasal

____](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-40-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

73 | Introduction to Linguistics

However, this rule doees not work for other similar

cases such as in ―buses‖ and ―passing‖, in which ―s‖ is

pronounced /s/. For this case, a number of conditions must be

added. The best way to do is by specifying vowel features that

can make this rule work. The vowel feature that can be added

here is [-low] which means that /s/ will change to /ʒ/ if the

vowels have ―low‖ feature. Thus, the rule can be formulated

like the following:

4.4 Conclusions

Structural phonologists championed the phoneme, an

abstract phonological unit consisting of a class of real sounds

called allophones. Phonemes are primarily determined by

investigating minimal pair. A variation of sound that does not

change the meaning is called allophone. When one sound has

more than one allophone, the sound is said to be in

complementary distribution.

Transformational-generative phonologists established

a more abstract level of phonology that consists of underlying

representation which is related to phonetic representations by a

system of rules that follow the form A → B/C. These rules

may add, delete, or change phonological elements.

Transformational-generative phonology is a universal theory of

phonology that is applicable to individual languages. However,

these rules are applicable only for regularities.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-41-320.jpg)

![Rusdi Noor Rosa

75 | Introduction to Linguistics

4.4.2 Questions for Discussions

1. How is phonology defined? What makes phonology

different from phonetics?

2. Which of the following pairs of words are minimal pairs?

a. thin – than d. write – right

b. bat – bats e. famous – fabulous

c. cut – put f. cap – map

3. Describe the following terms. It is suggested to provide an

example for each.

a. phoneme

b. allophone

c. complementary distribution

4. What sounds are presented by the italicized letters in the

following words? Provide an allophonic (narrow)

transcription.

a. spirit d. sing

b. cab e. skip

c. bed

5. What are the differences between segmental phoneme and

suprasegmental phoneme?

6. Show the various meaning of the following sentences

through different variable stress.

a. He always puts his bag here

b. She never asked me to leave

7. Write rules that express the following:

a. A sound[n] becomes [ŋ] when it precedes [k]

b. A consonant [g] is deleted when it precedes [h]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phoneticsandphonology-150205030615-conversion-gate02/85/Phonetics-and-phonology-43-320.jpg)