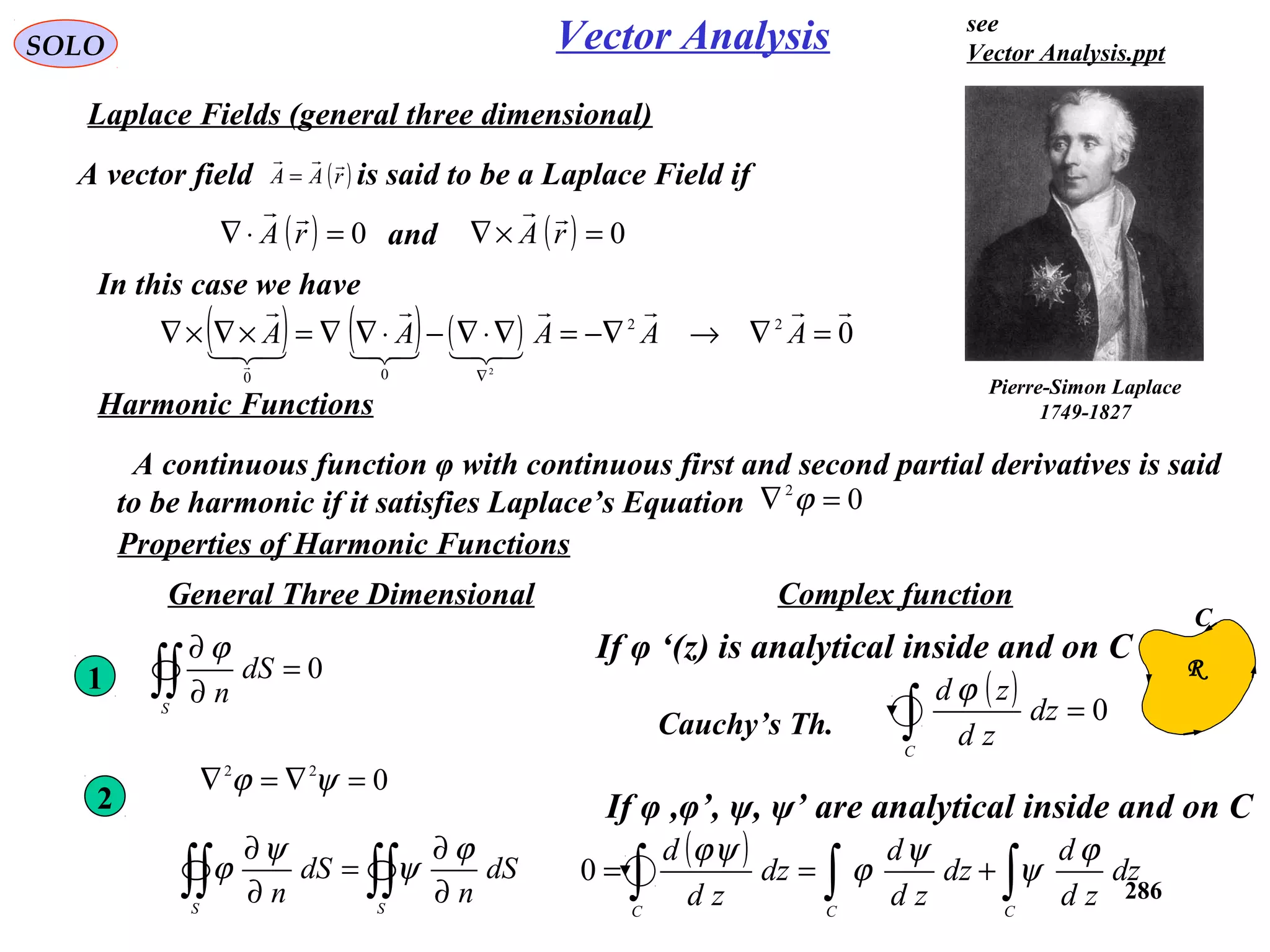

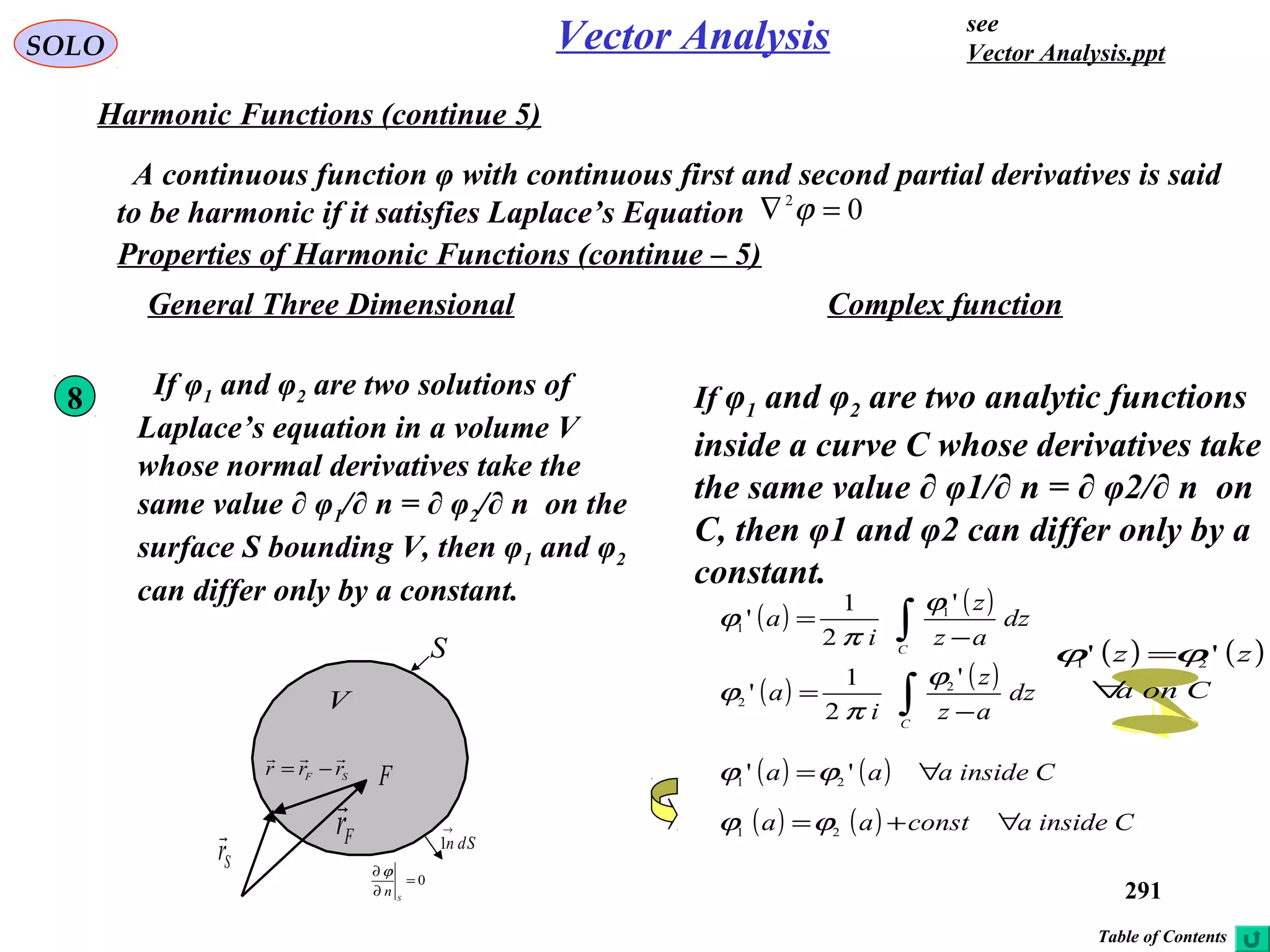

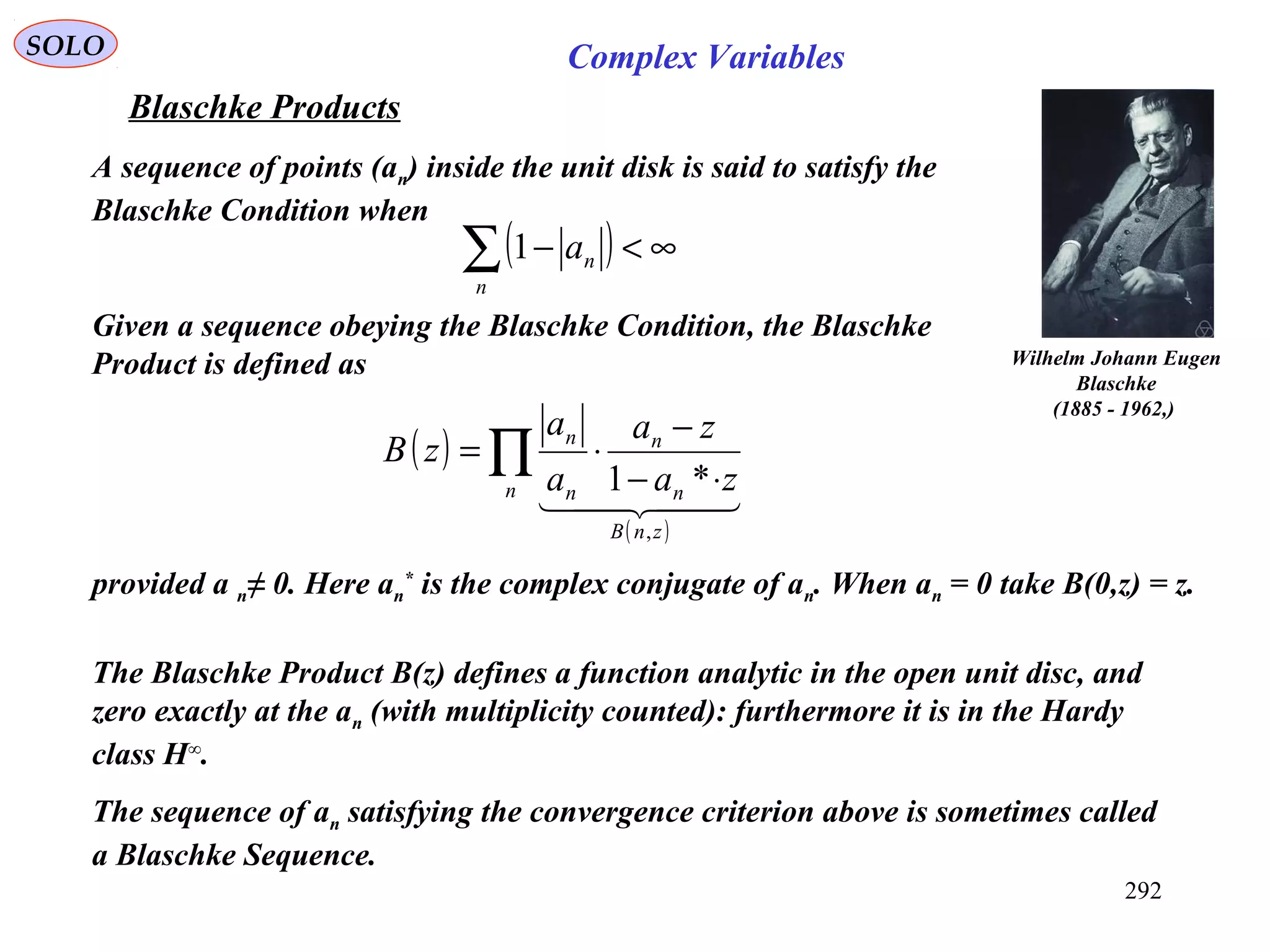

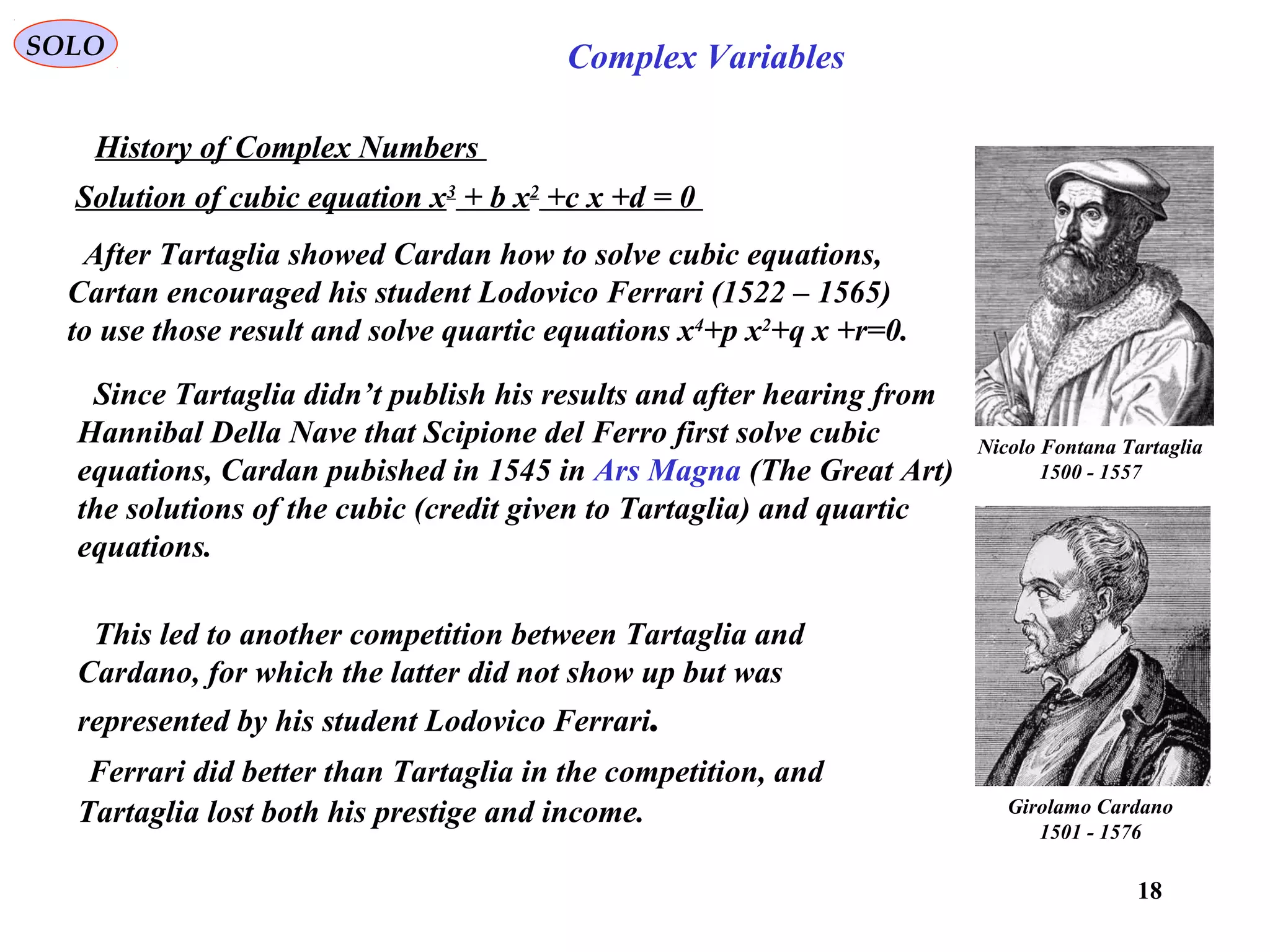

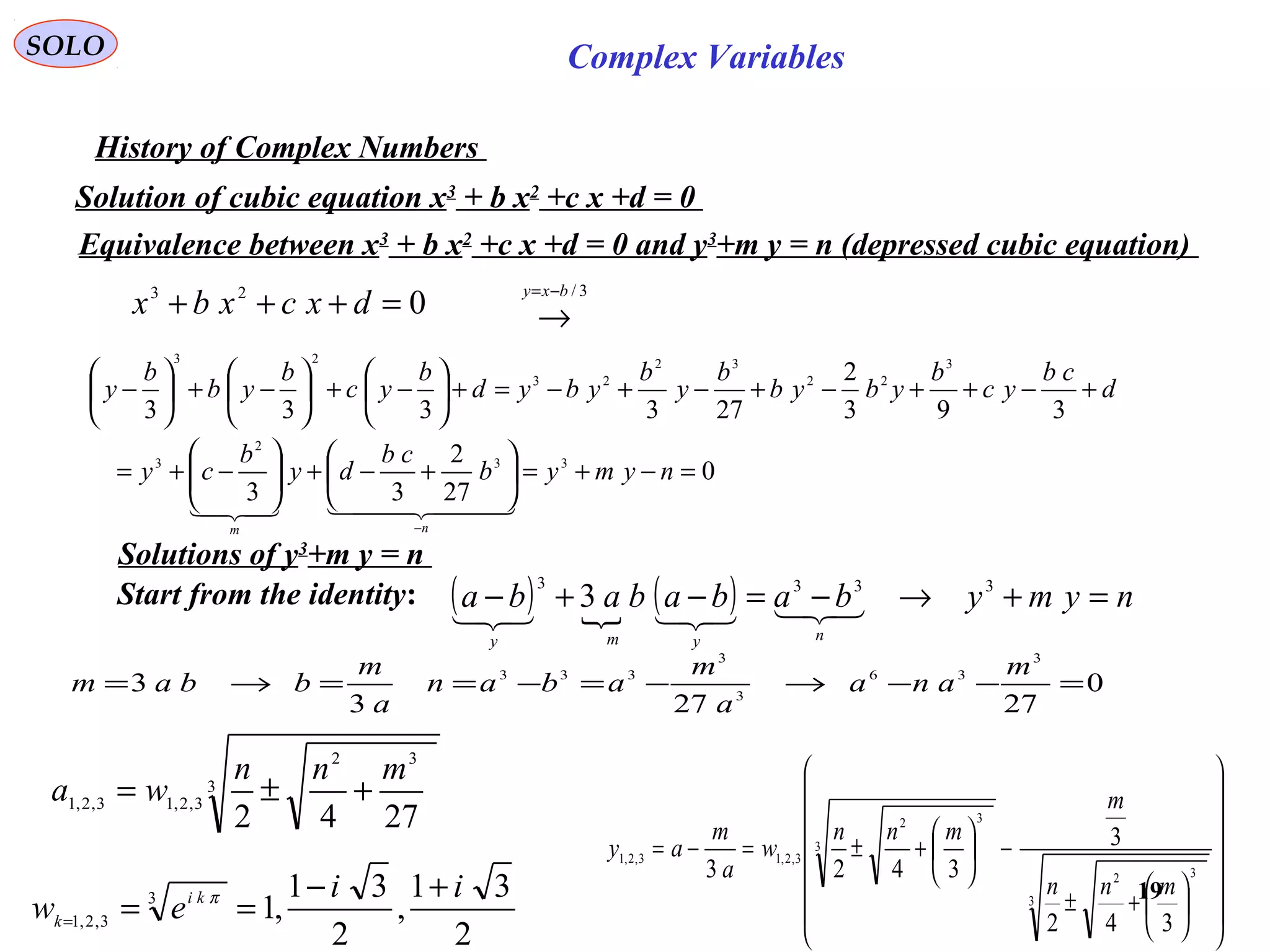

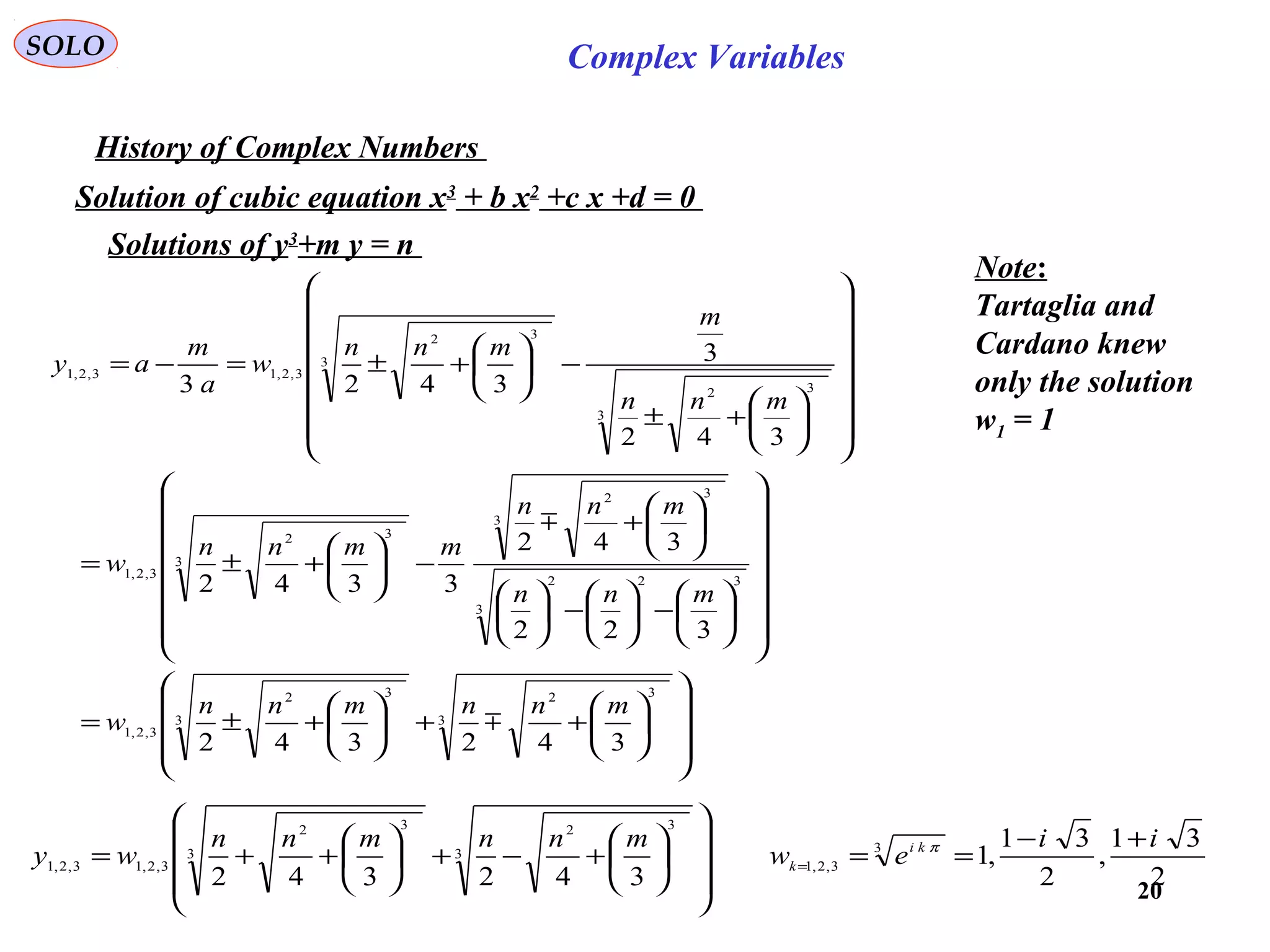

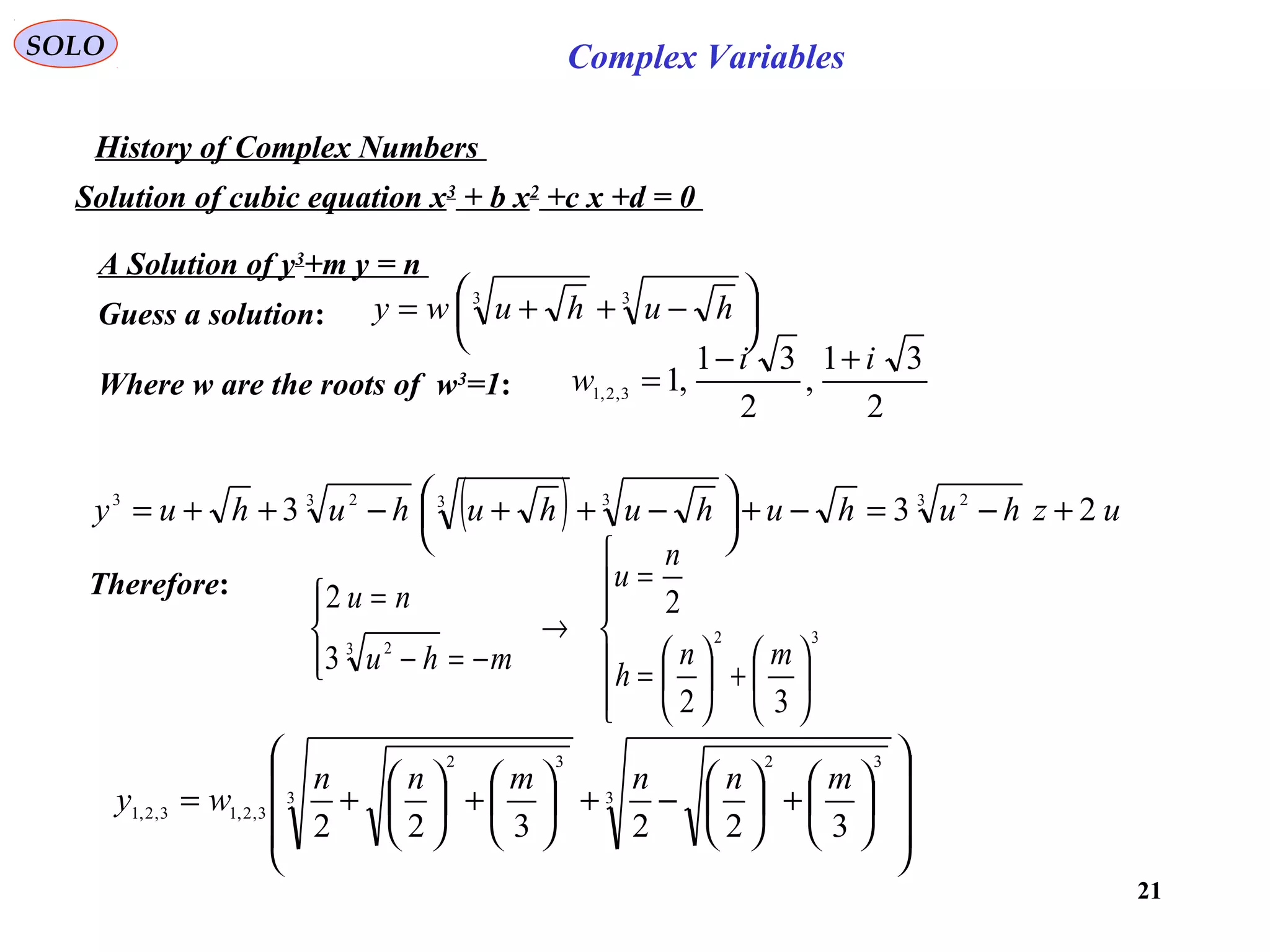

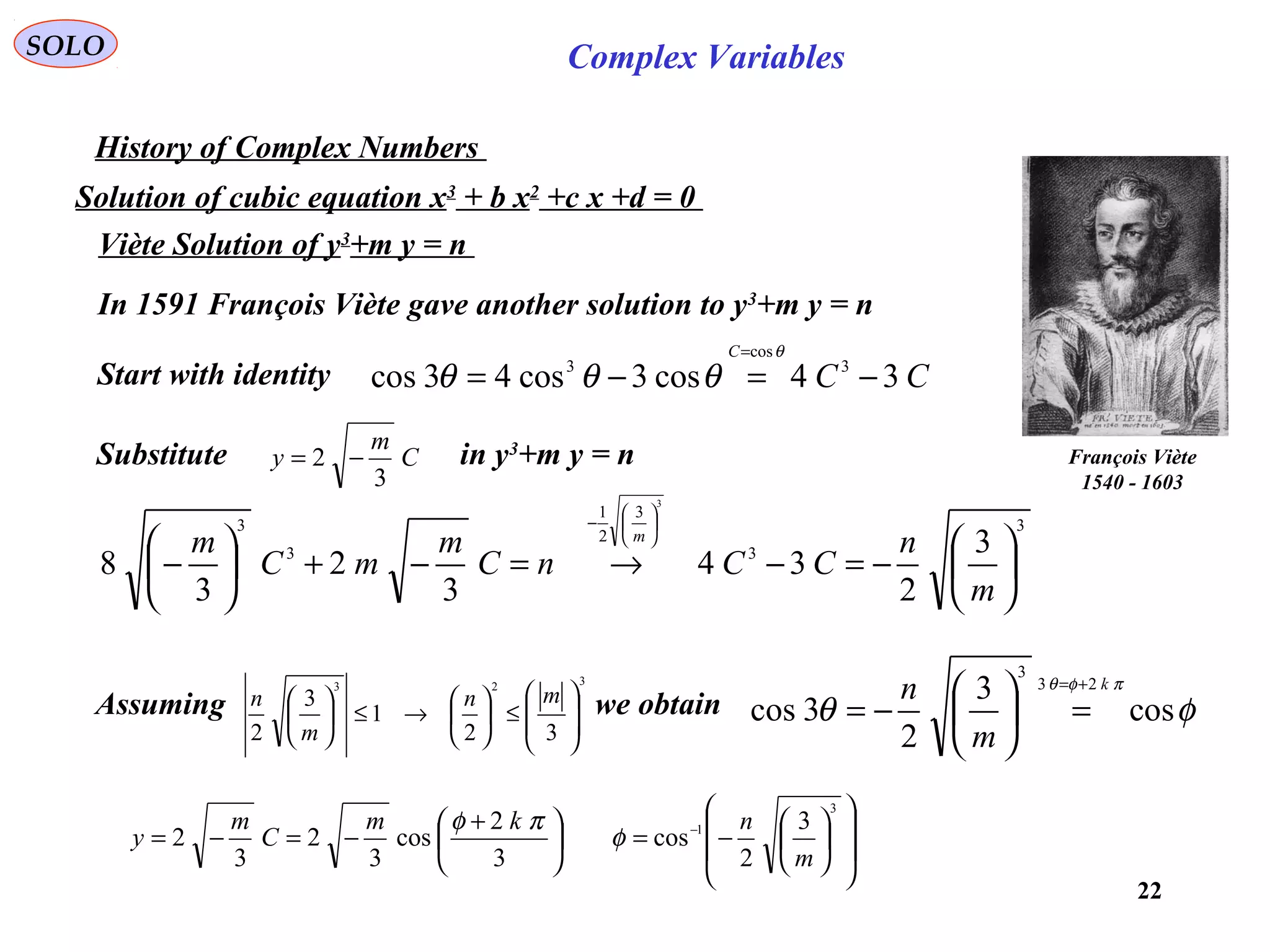

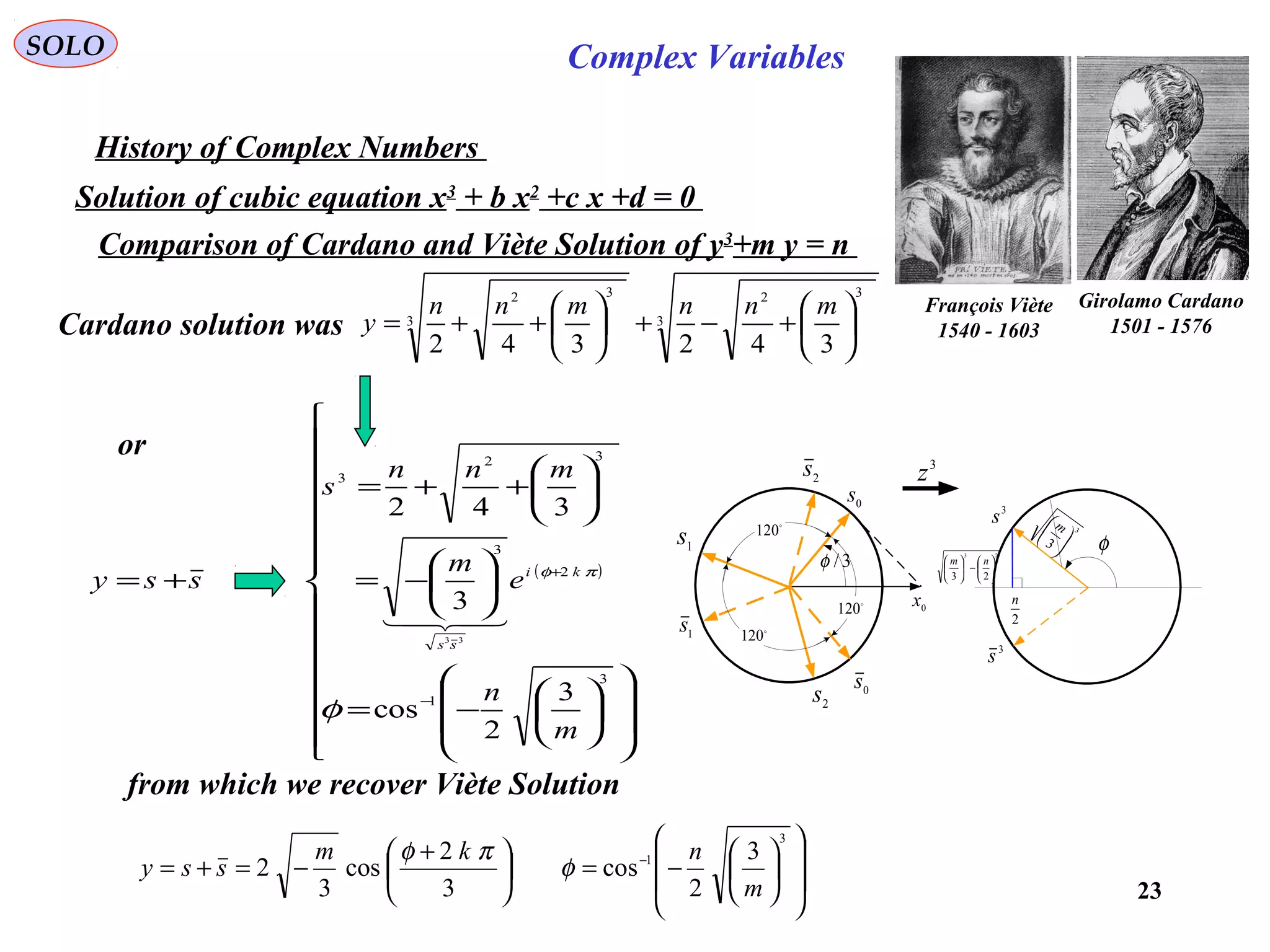

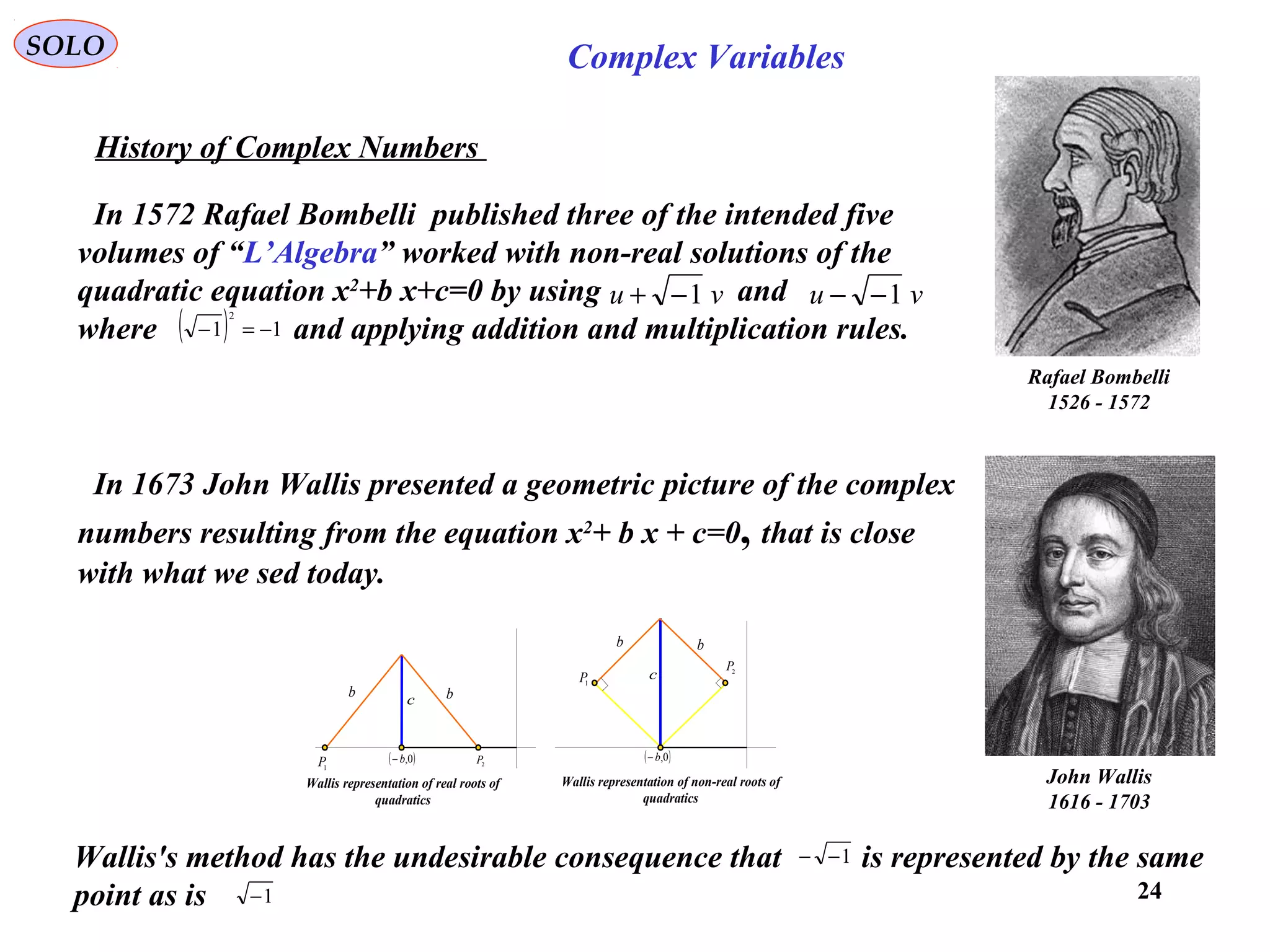

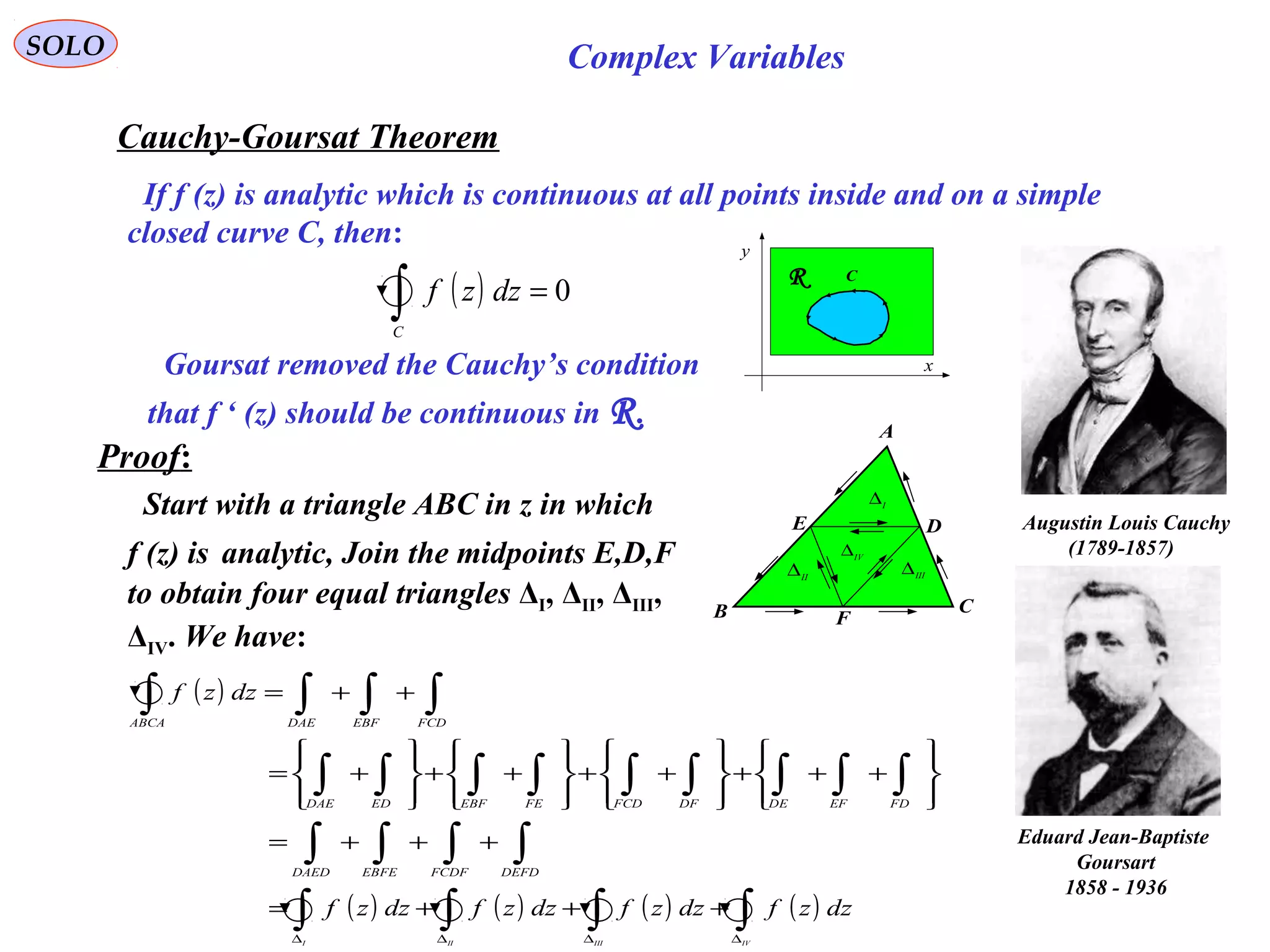

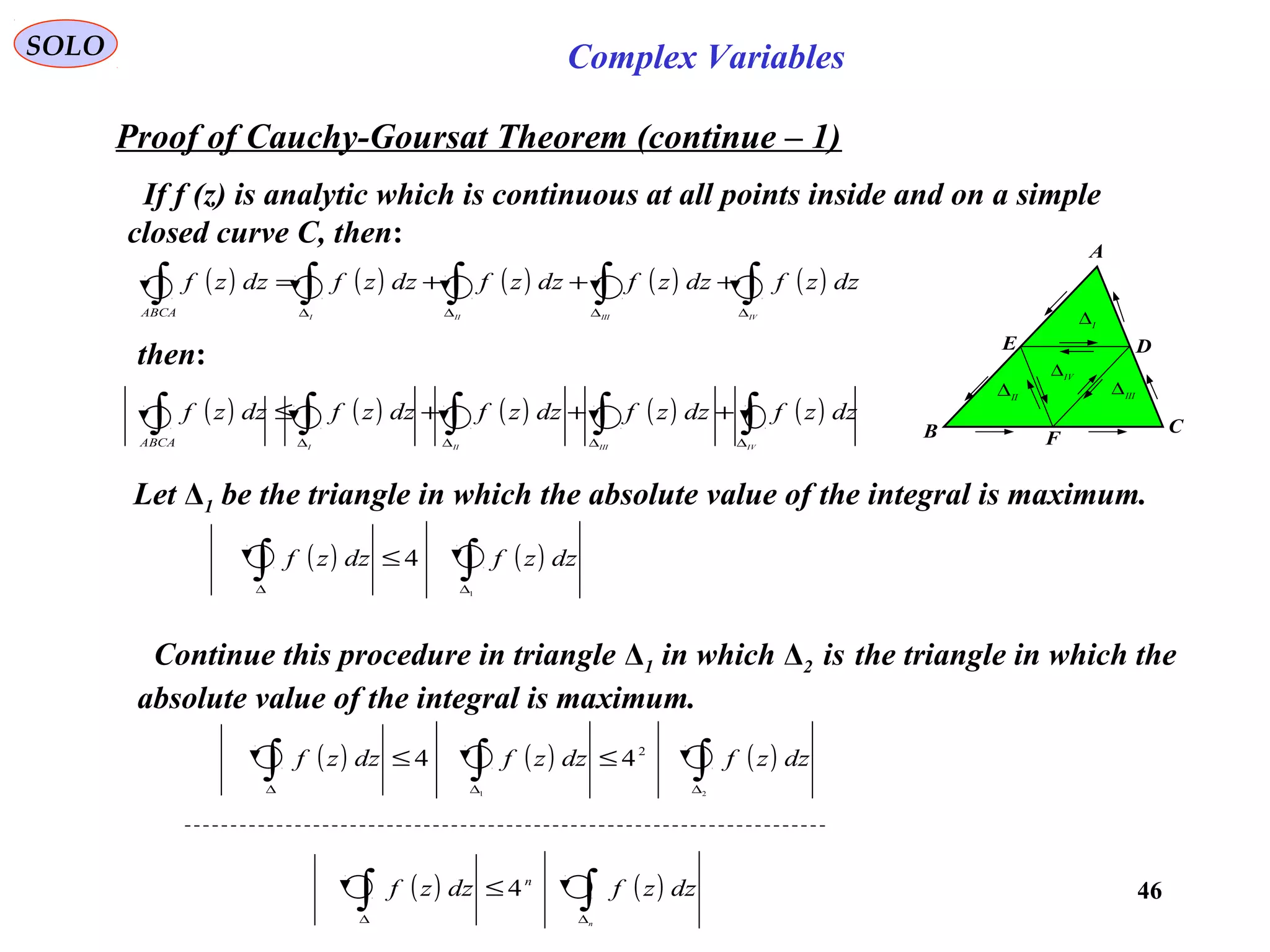

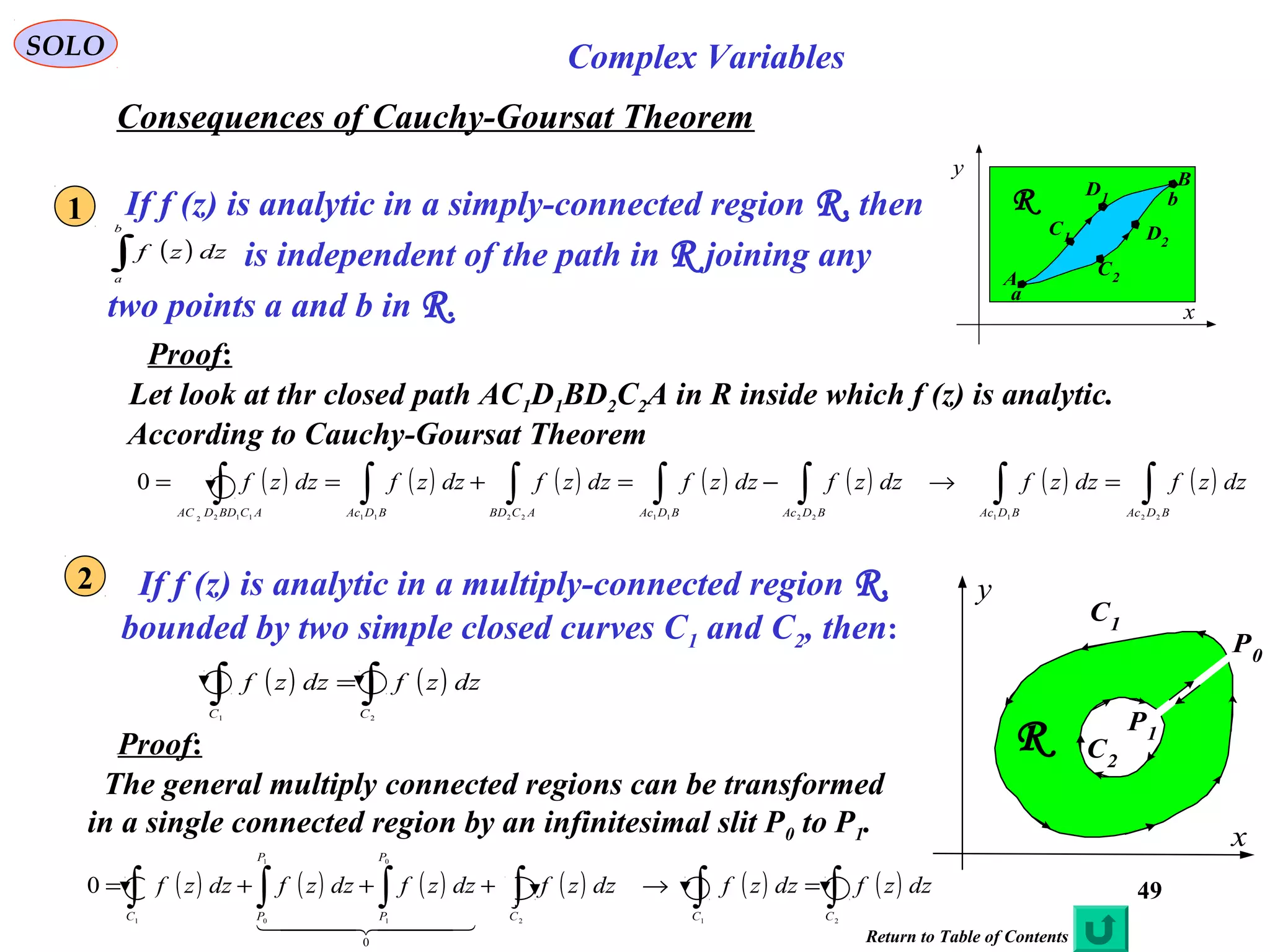

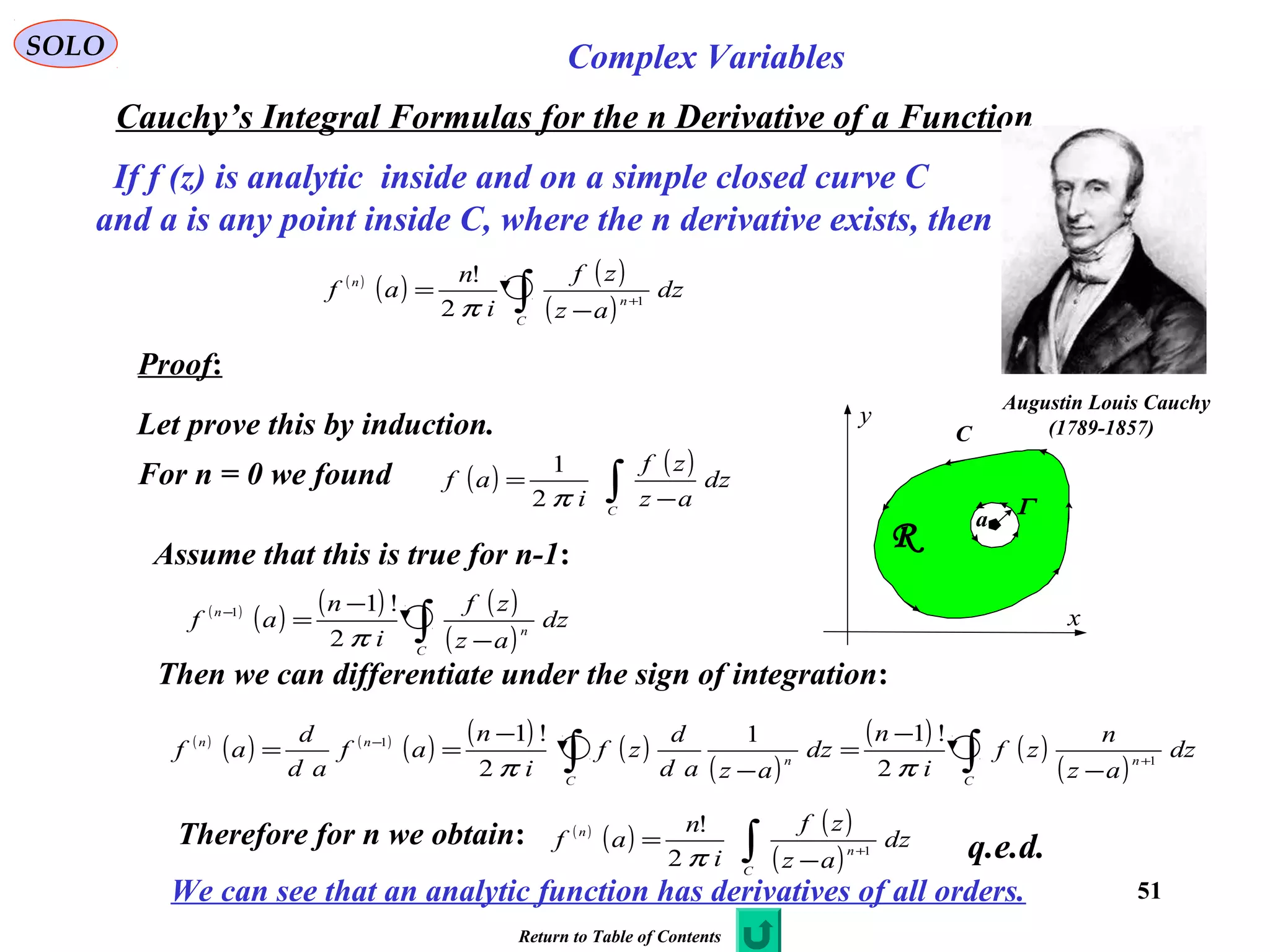

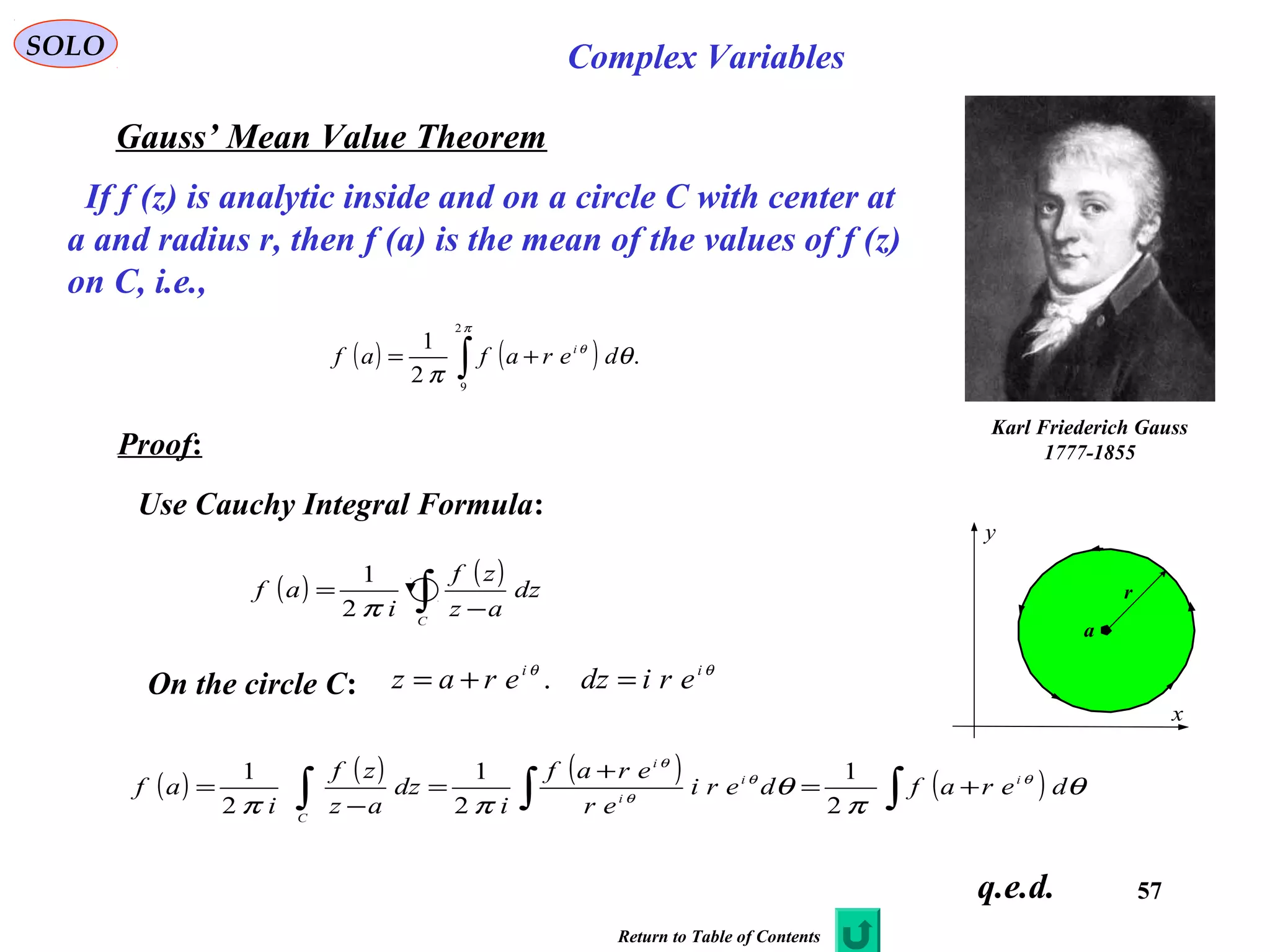

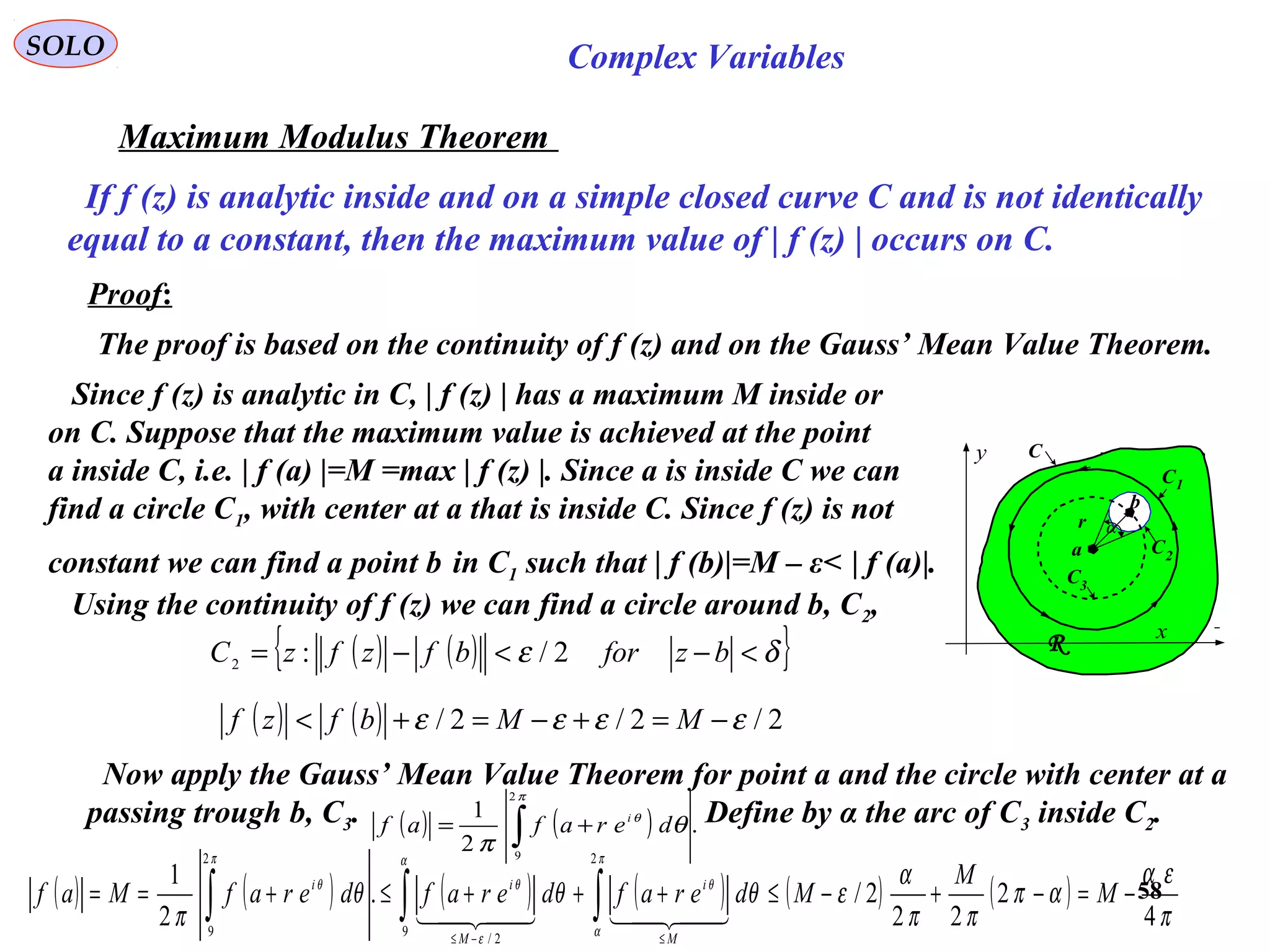

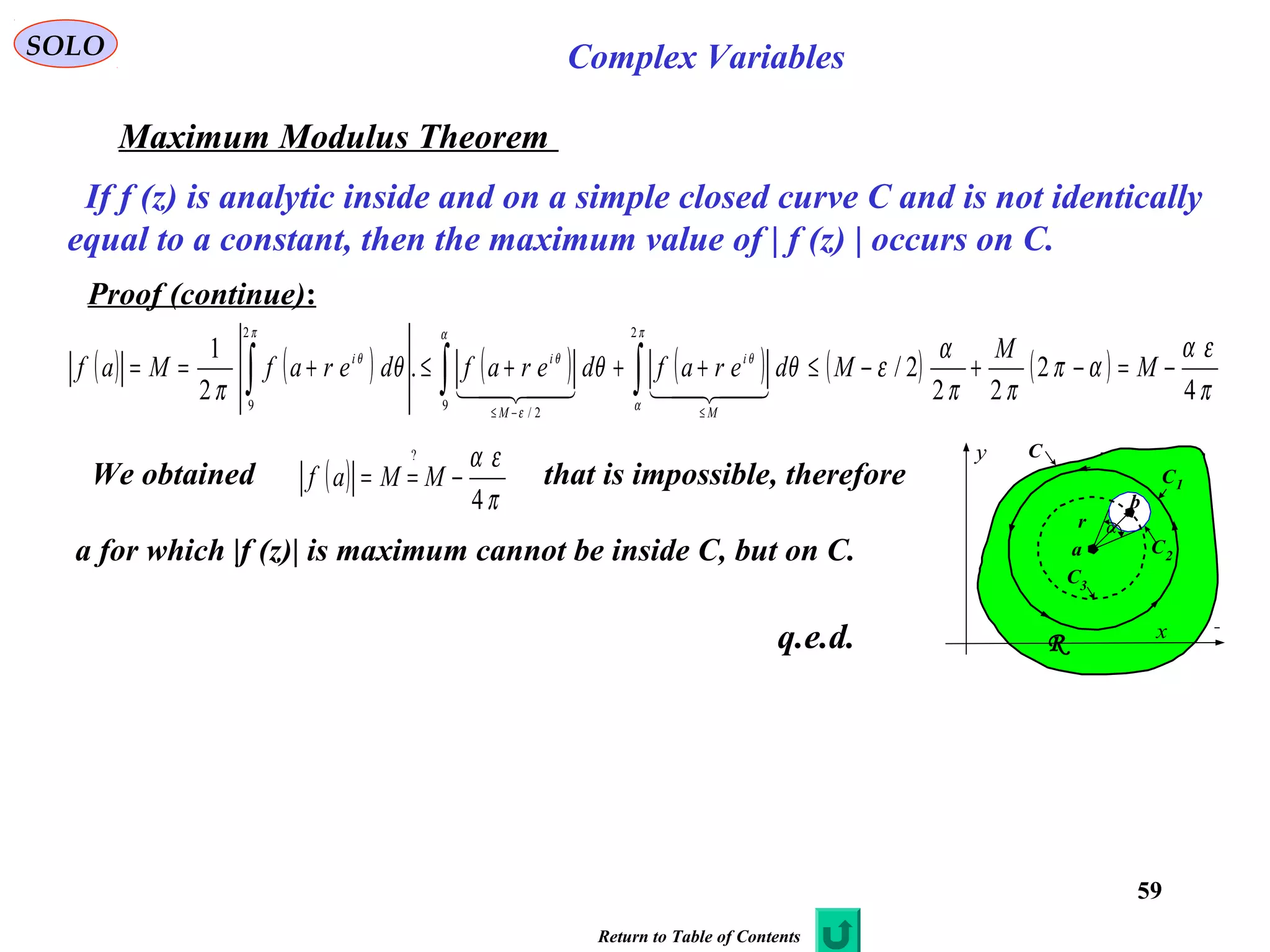

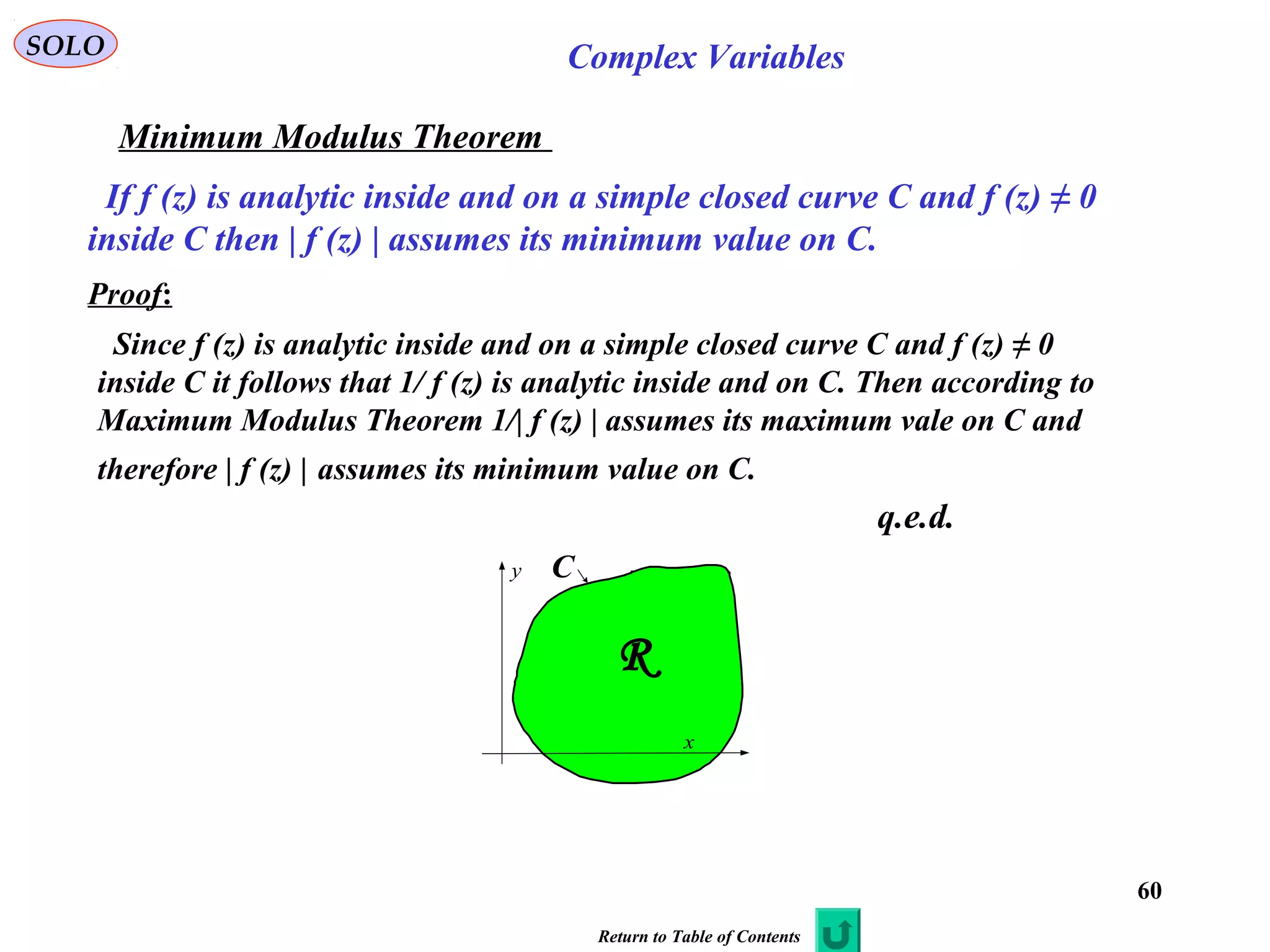

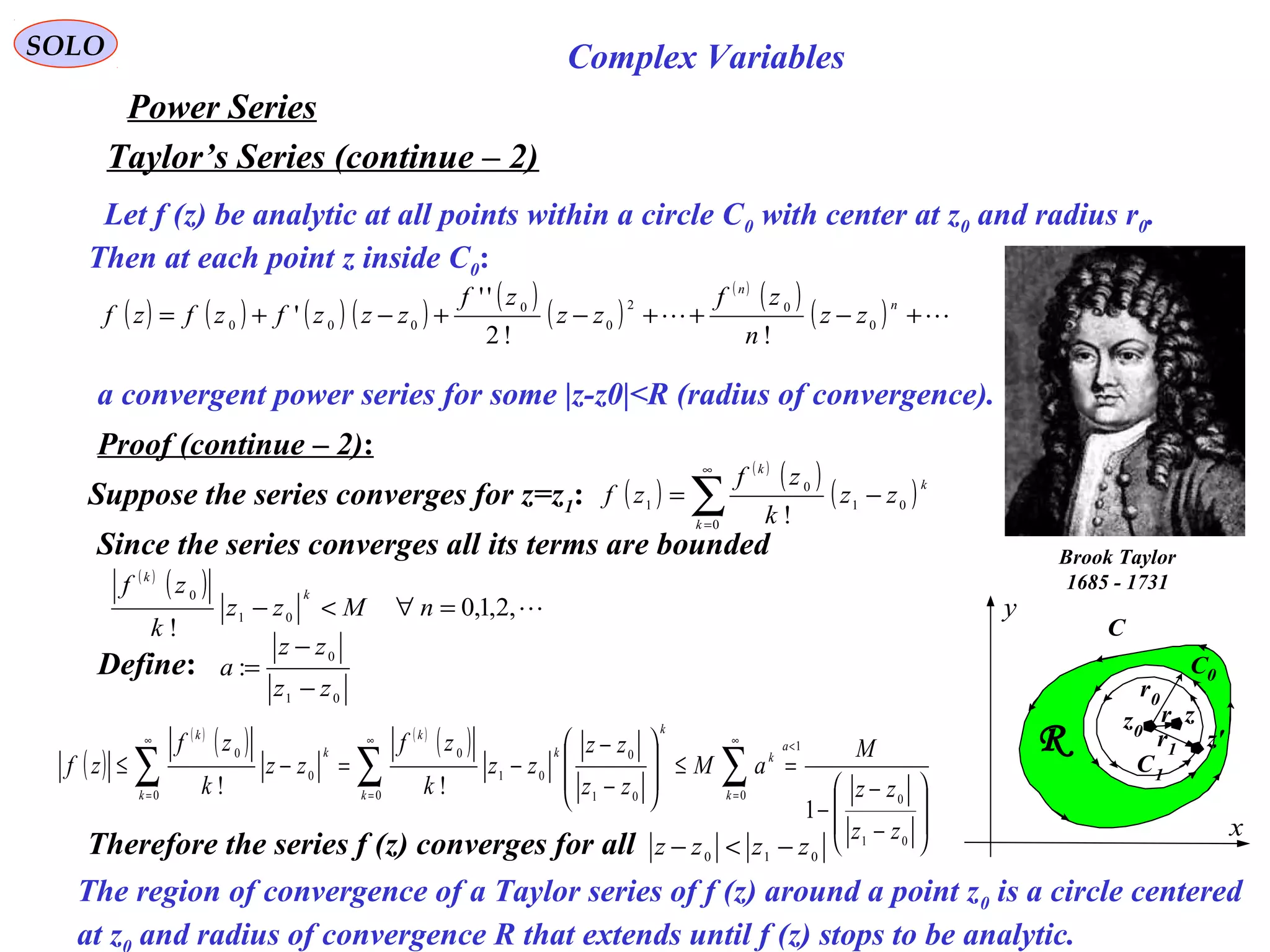

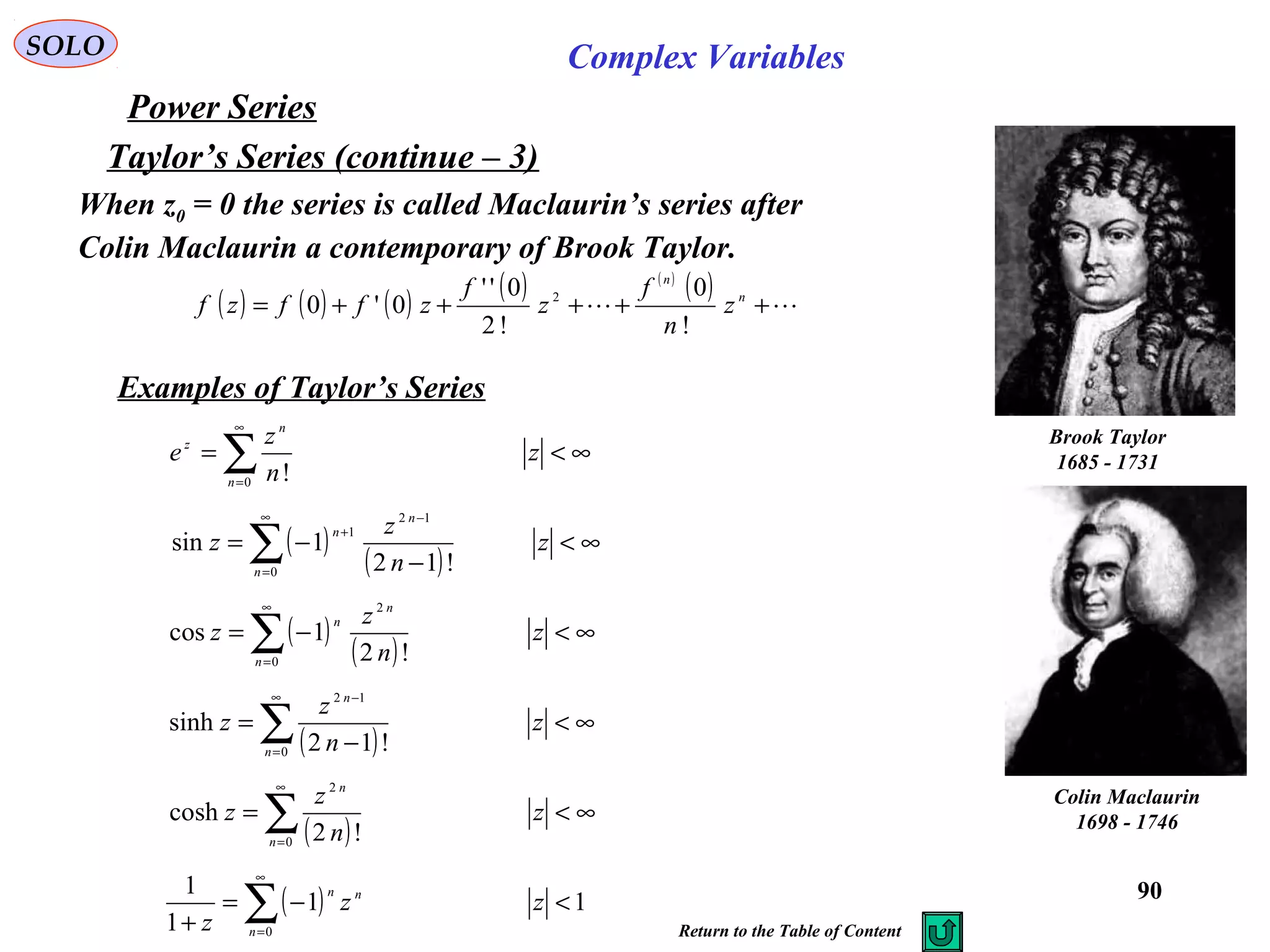

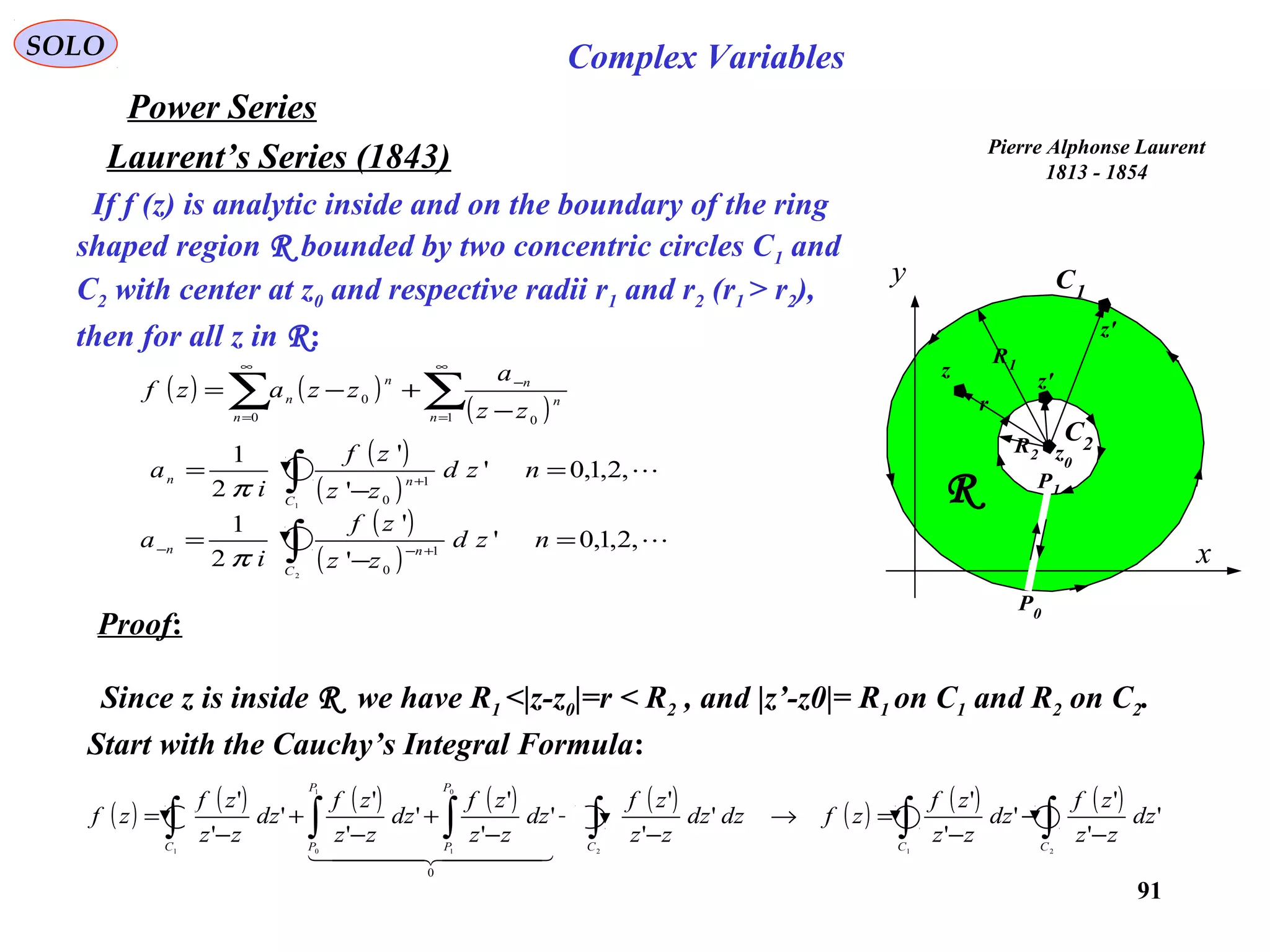

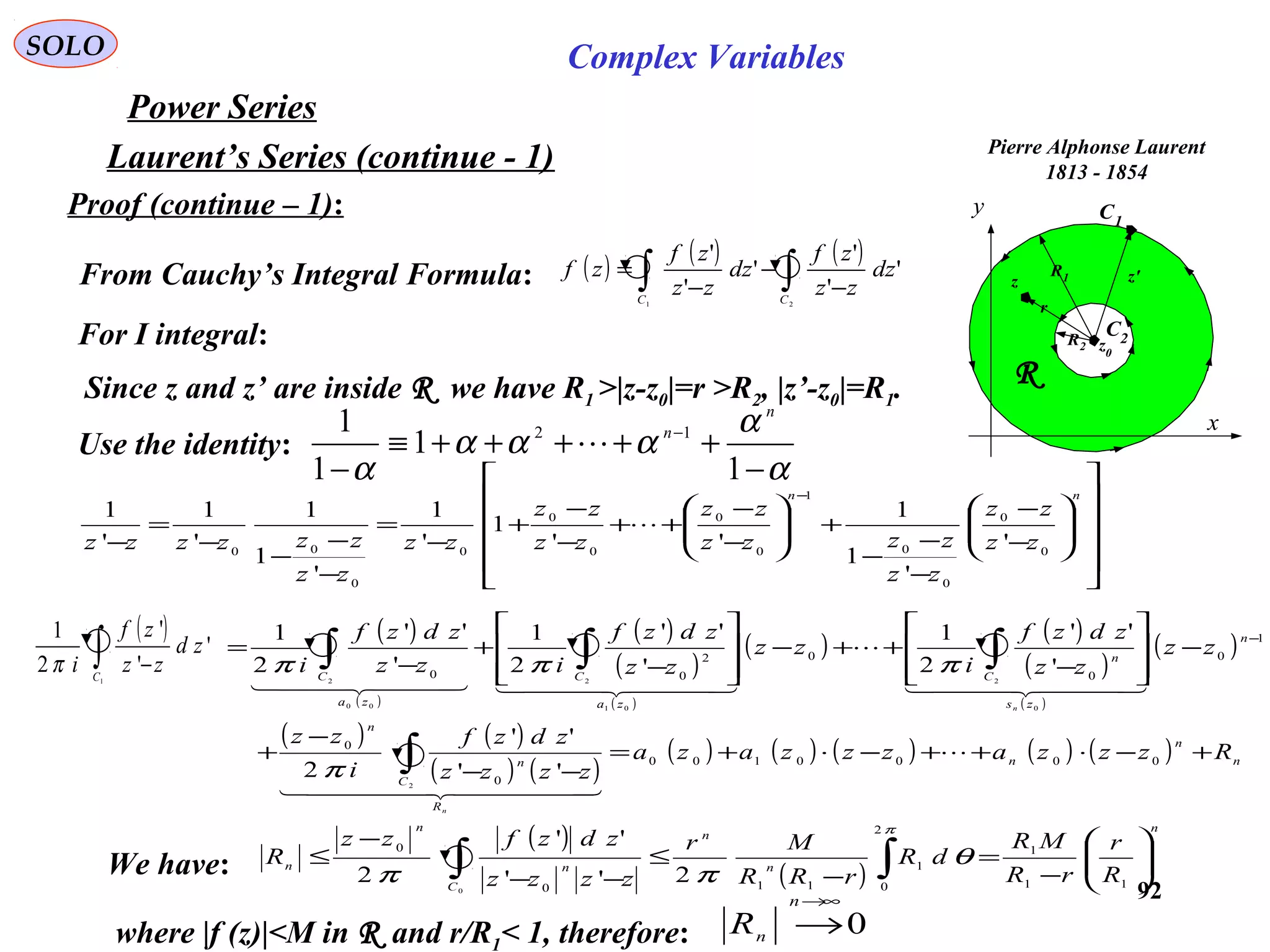

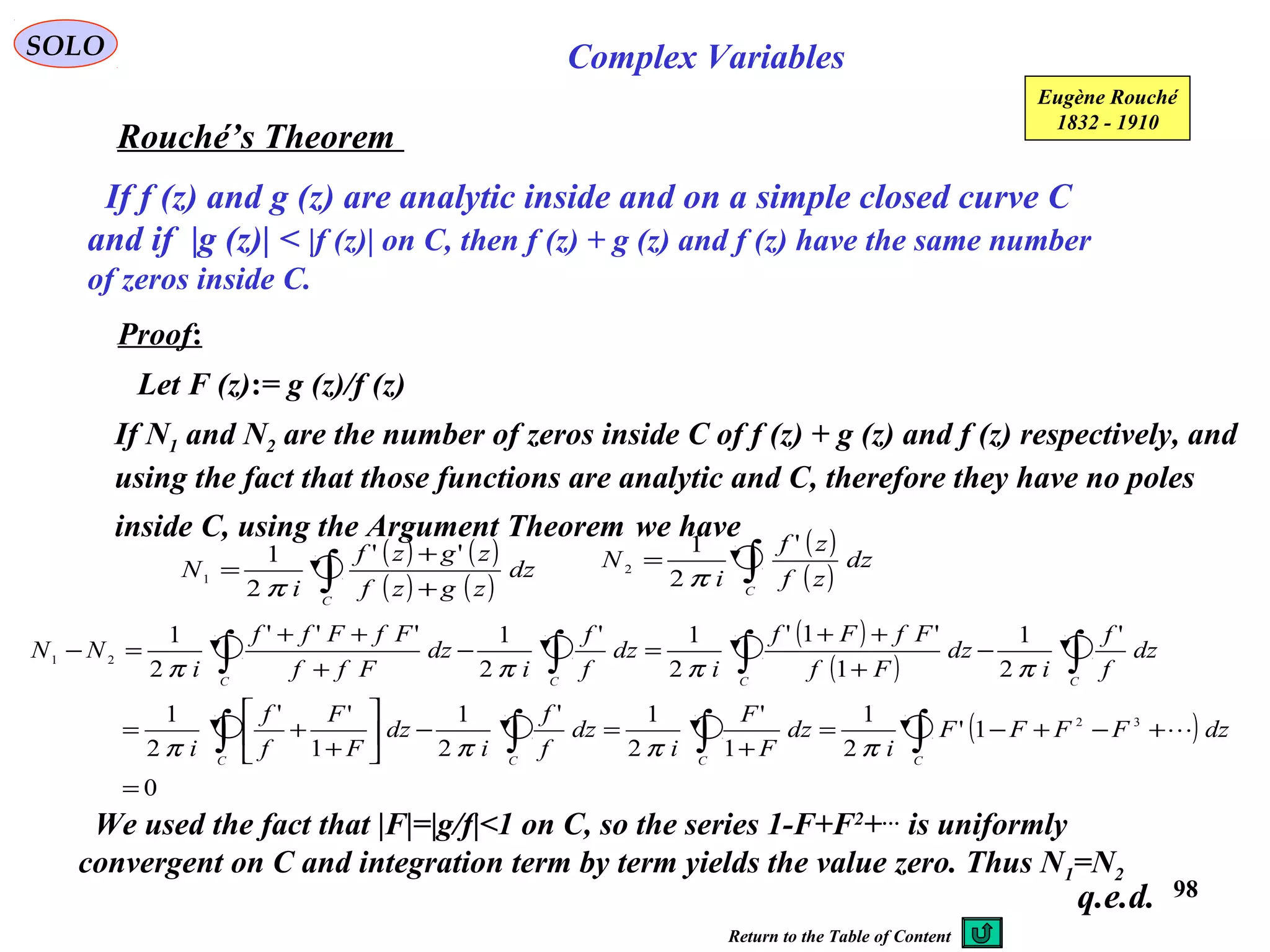

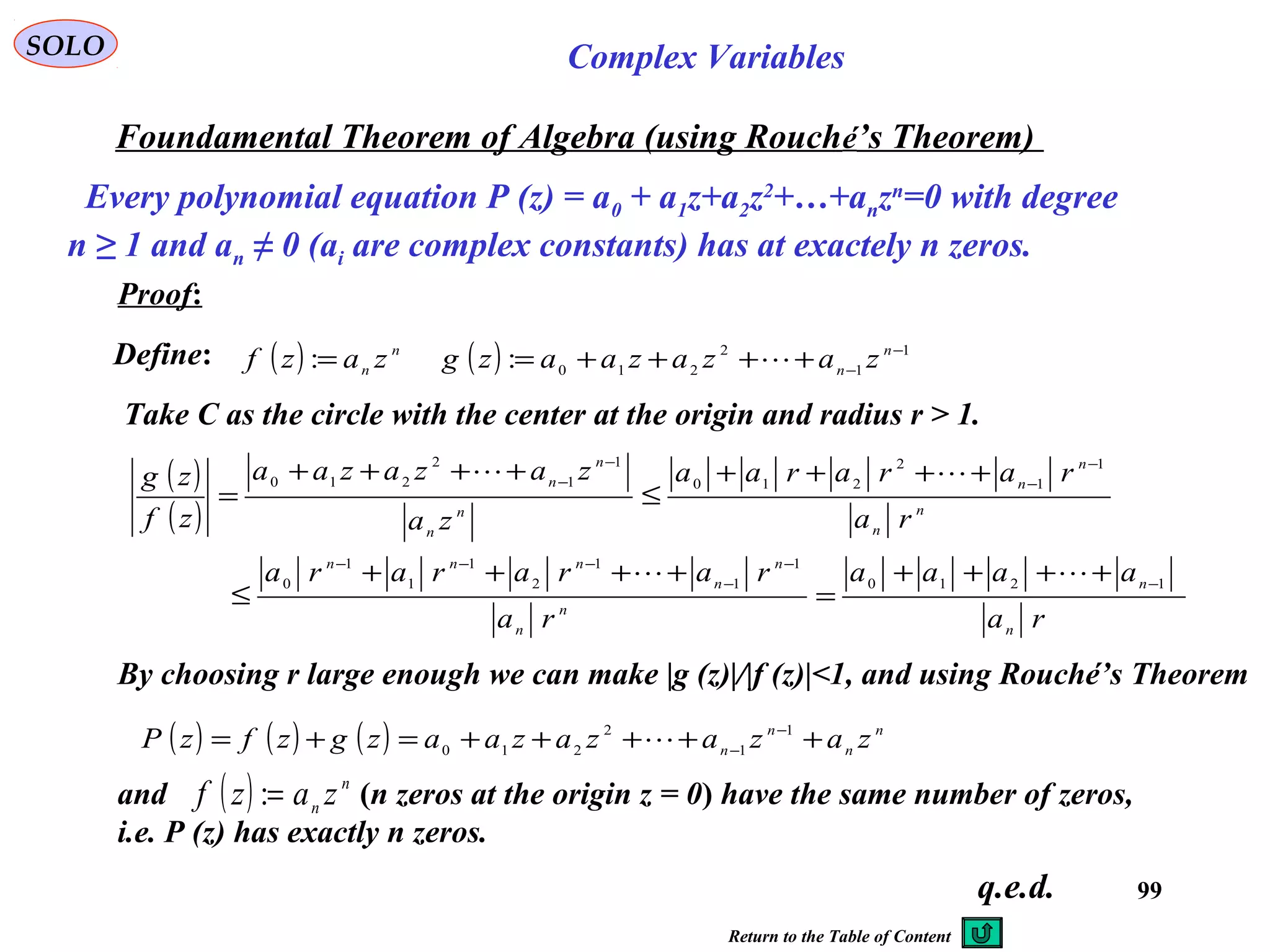

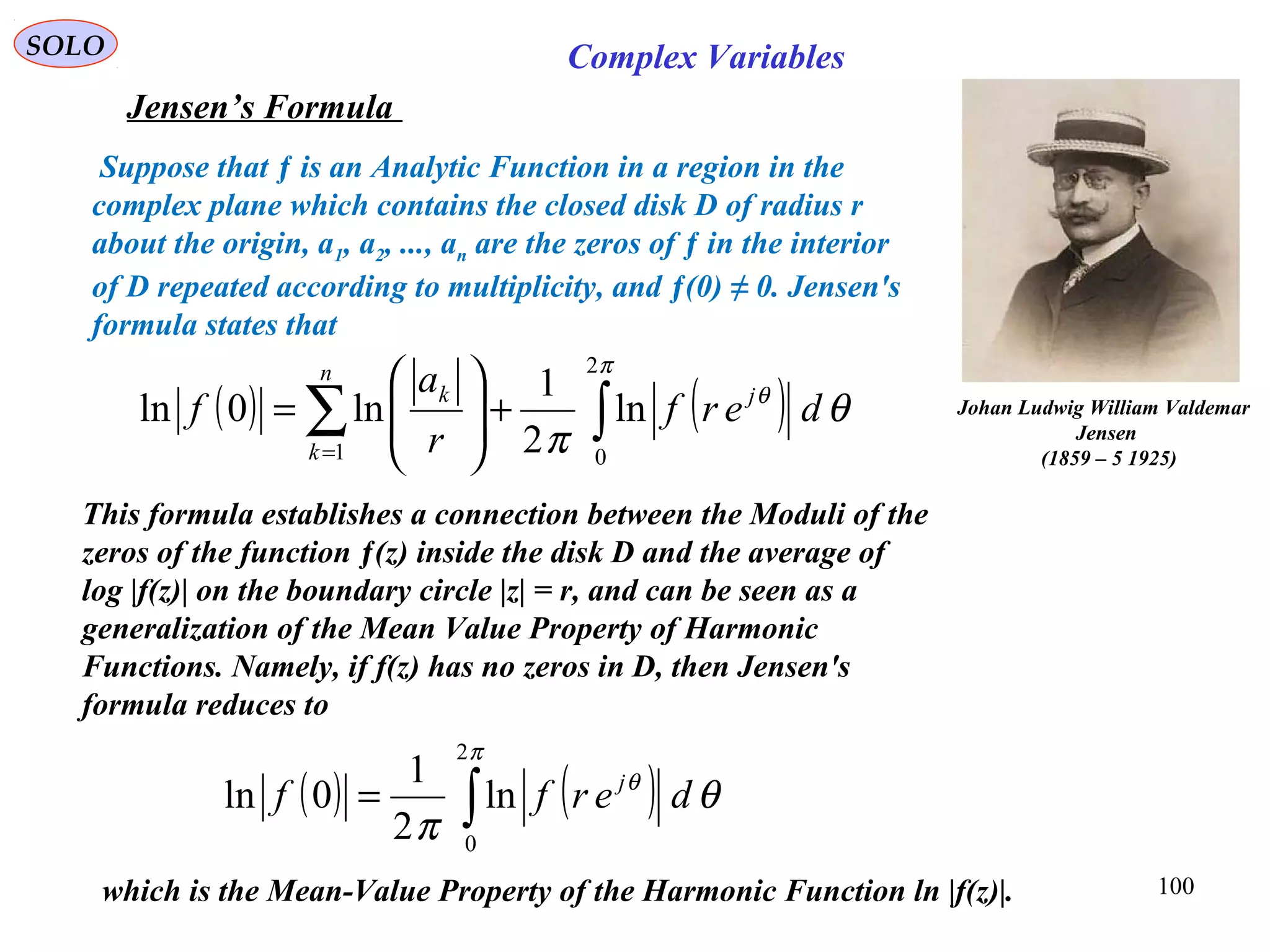

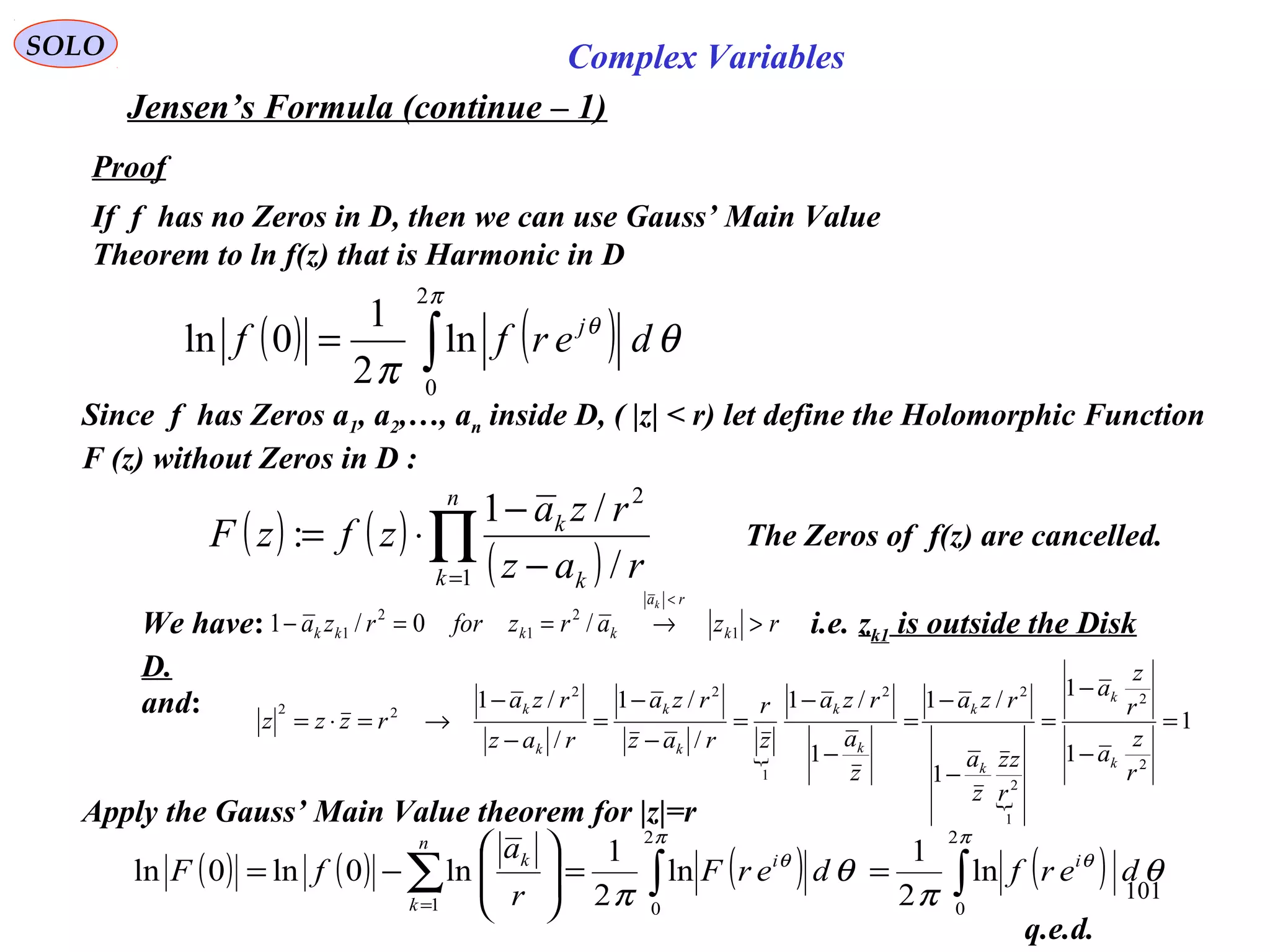

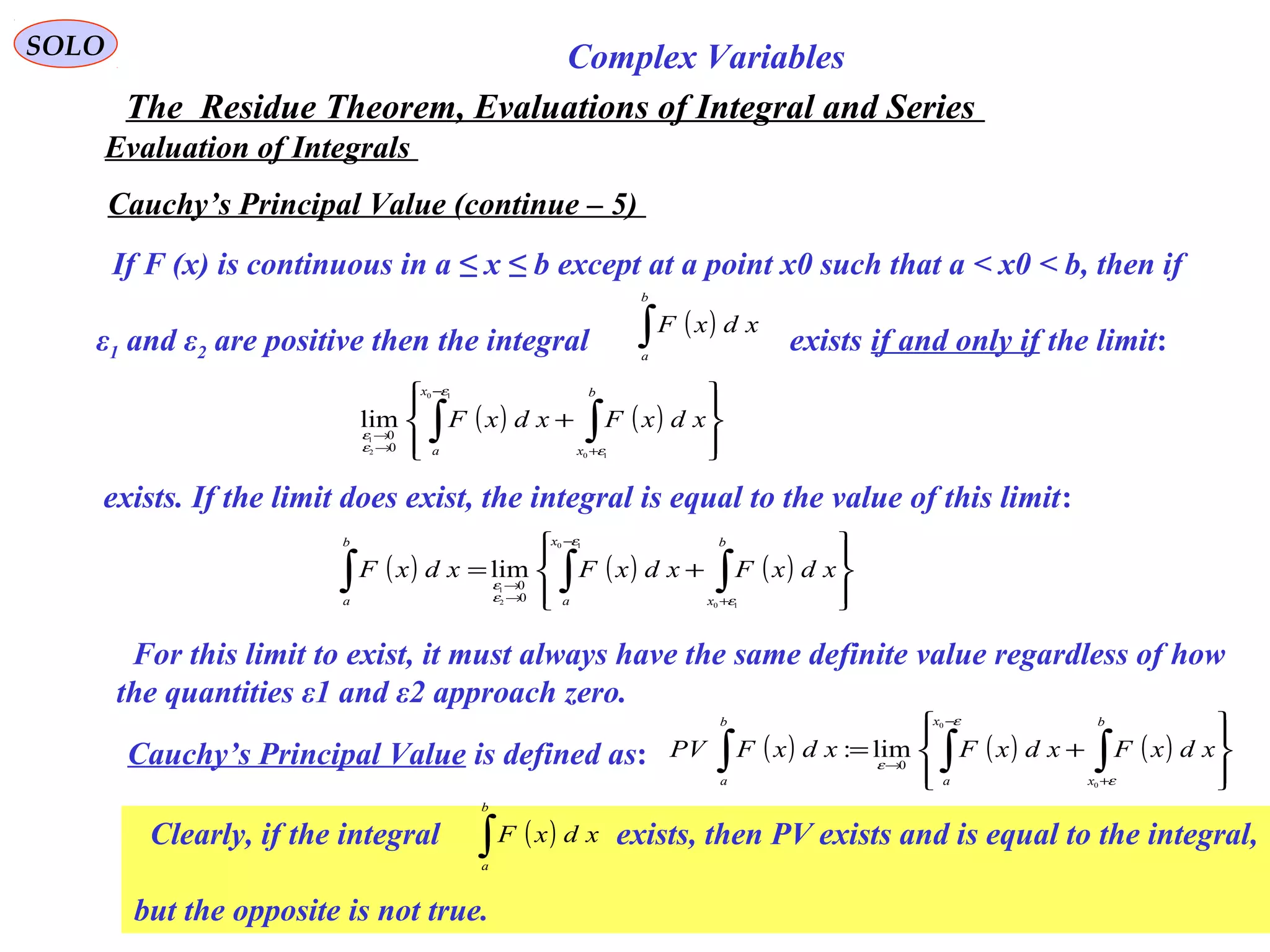

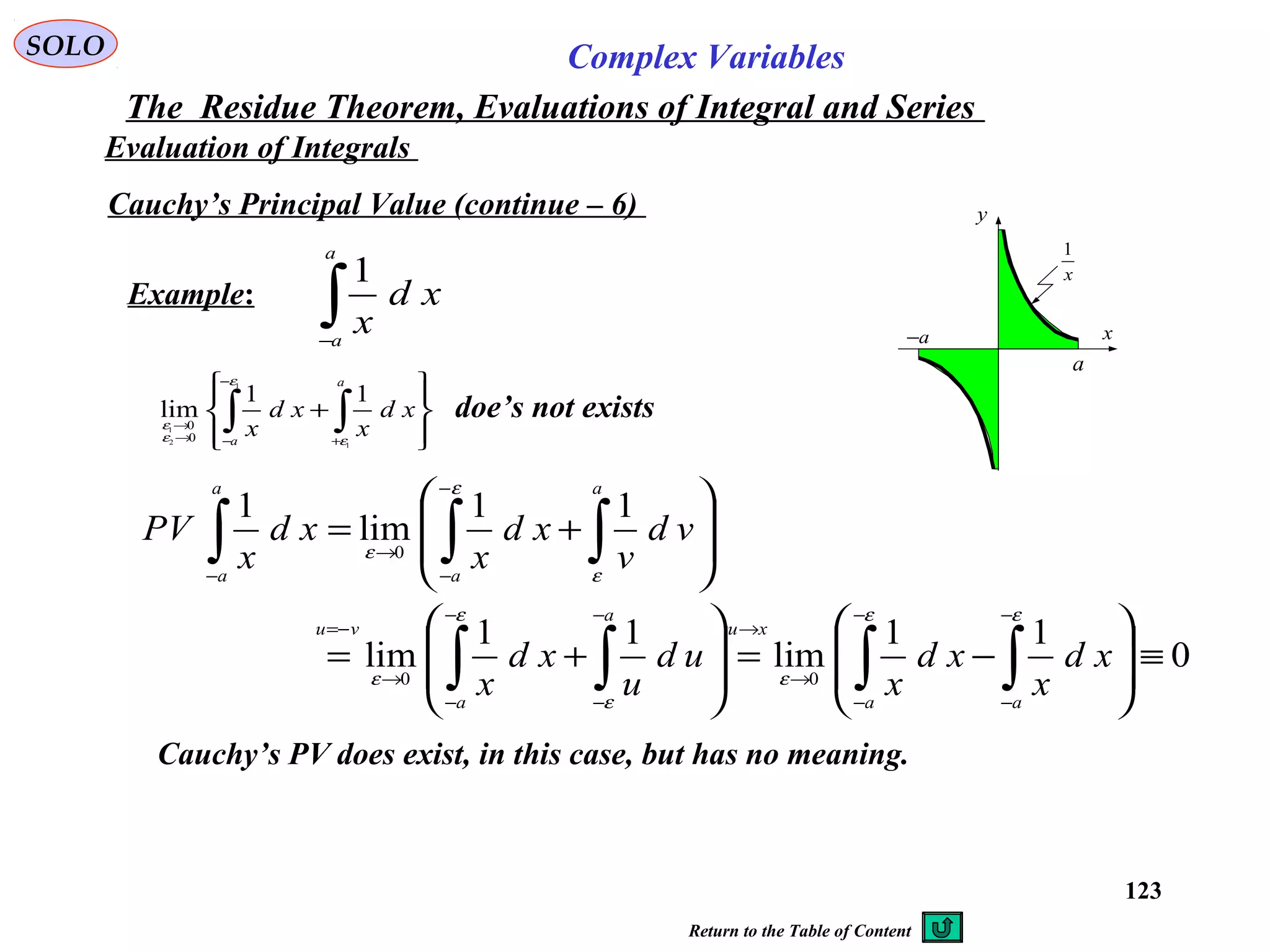

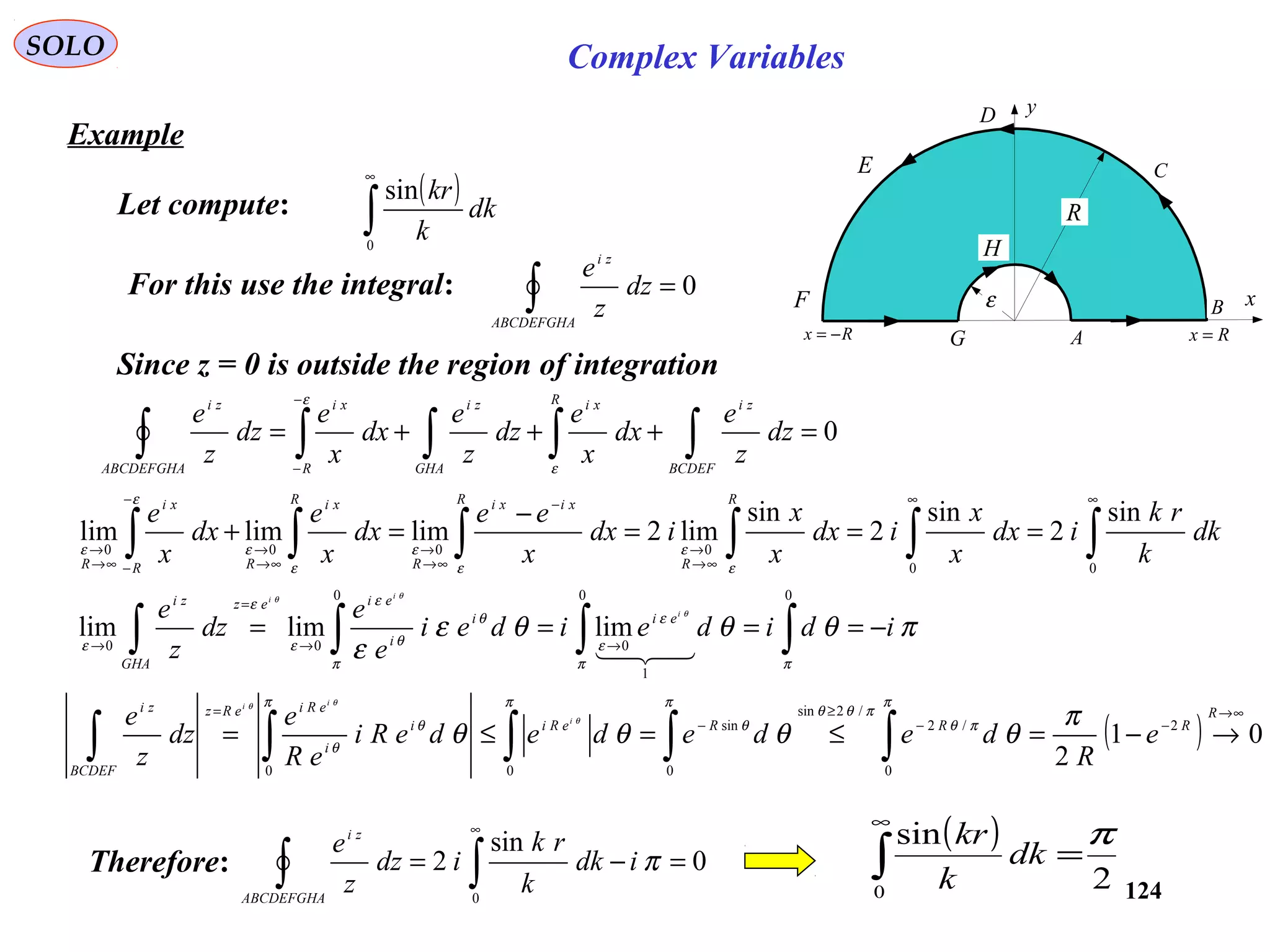

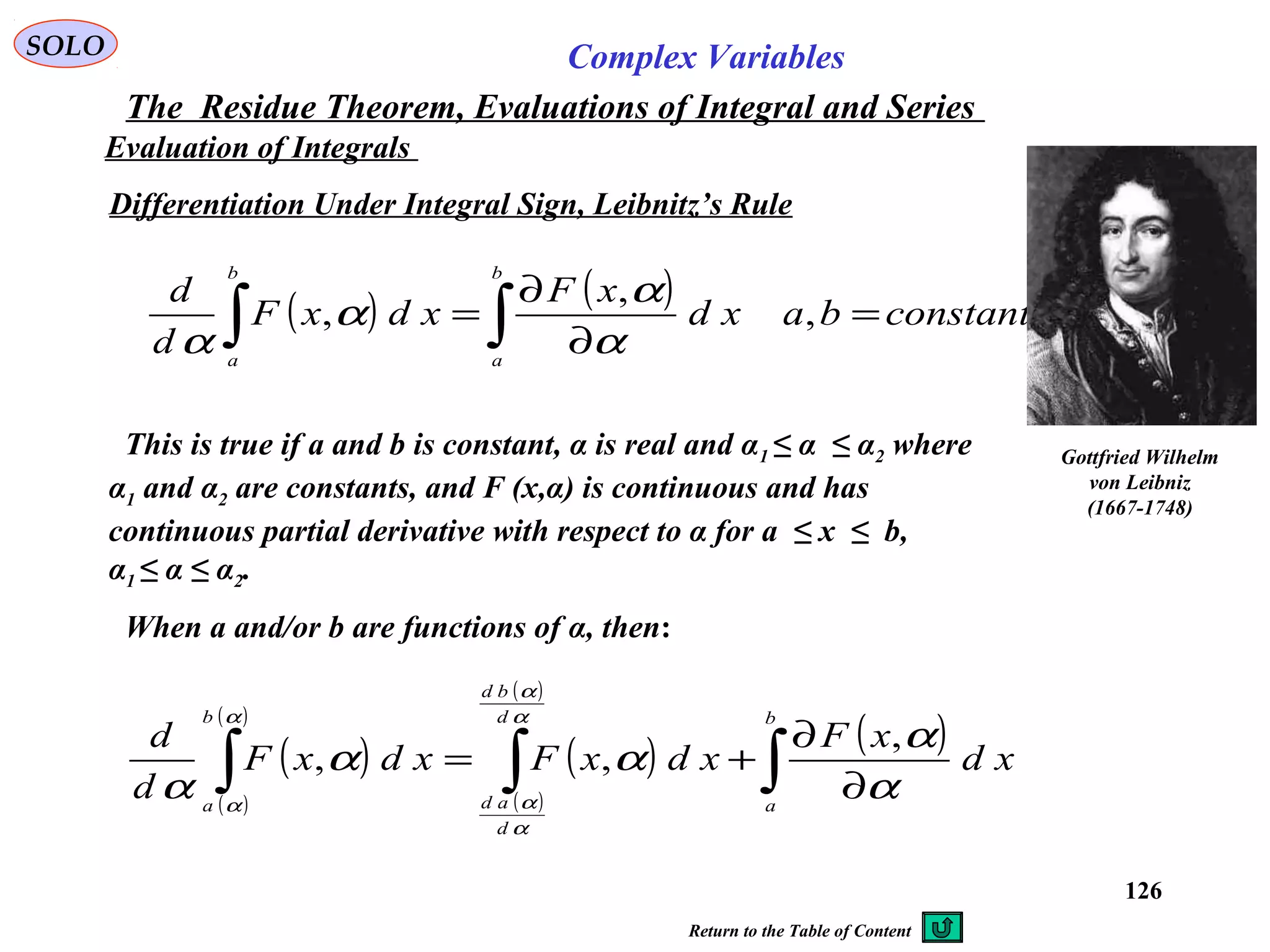

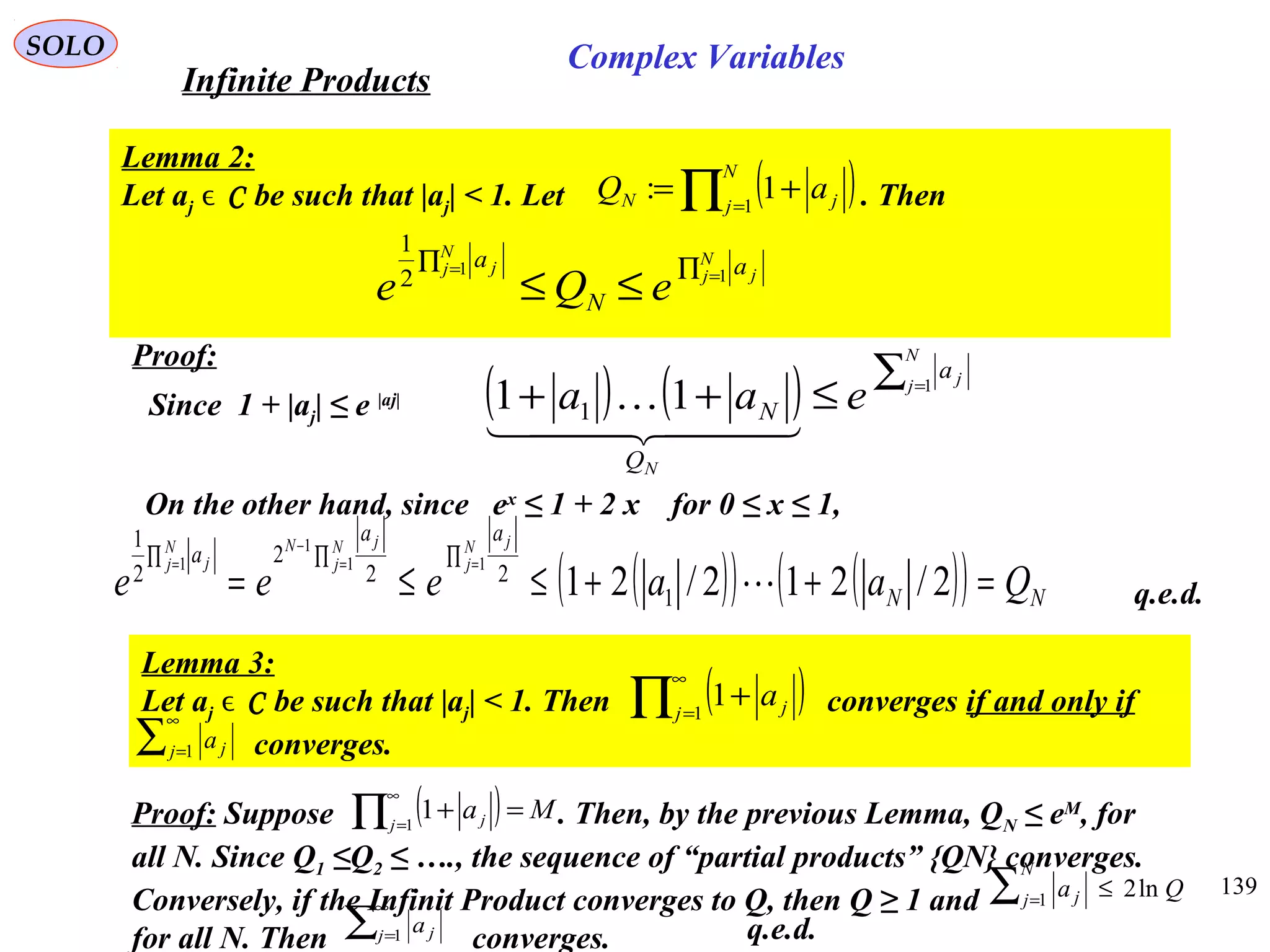

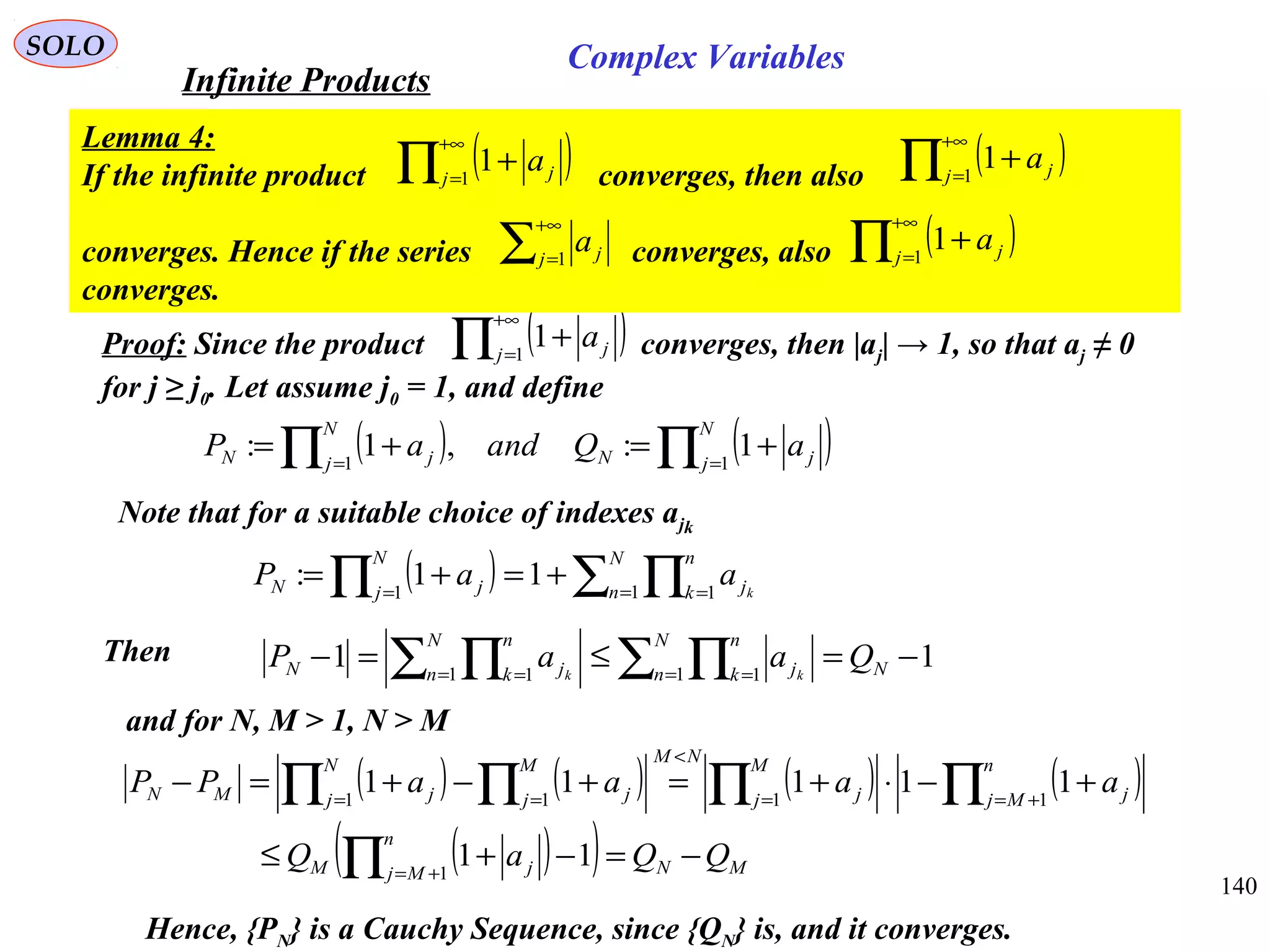

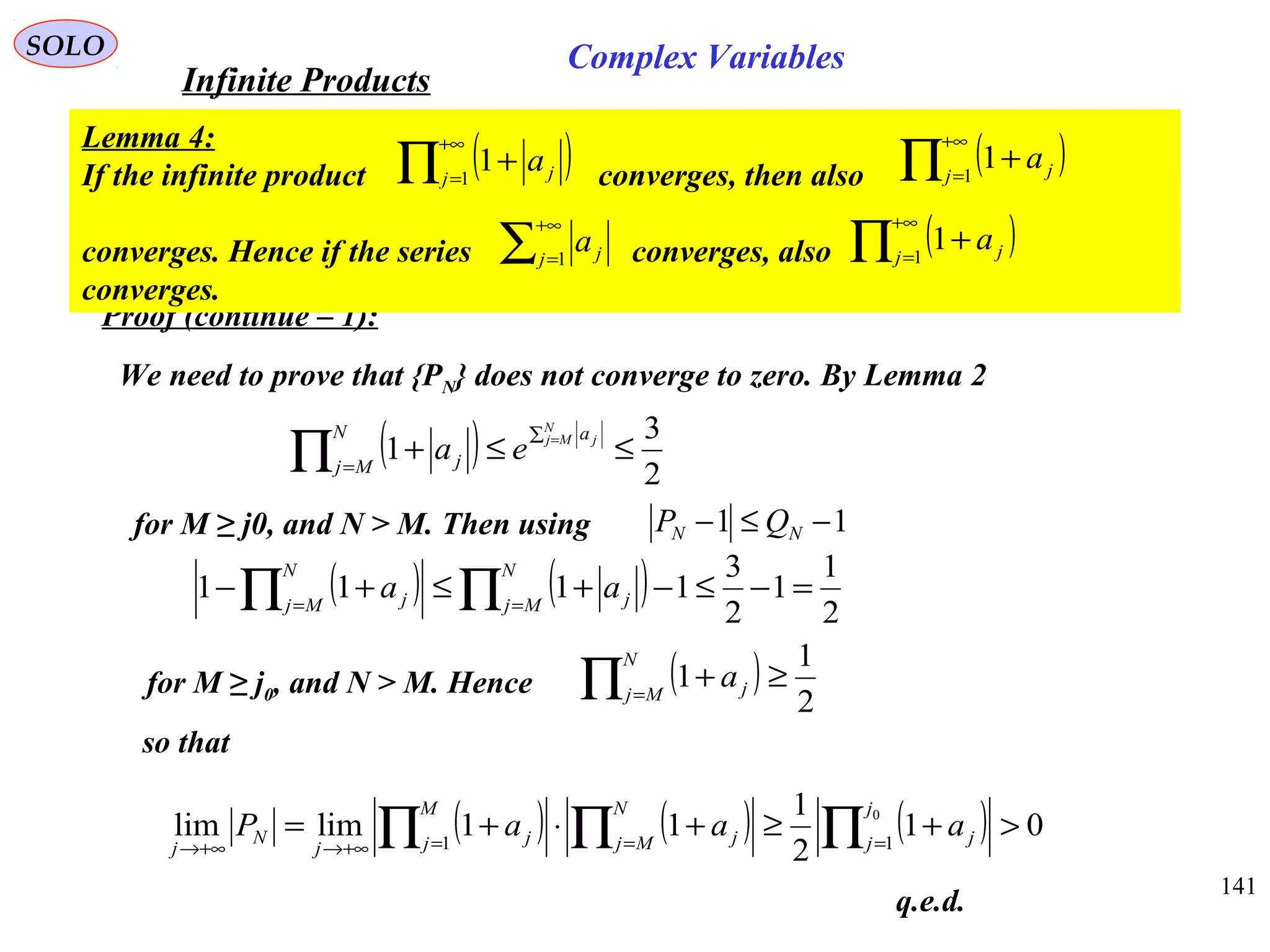

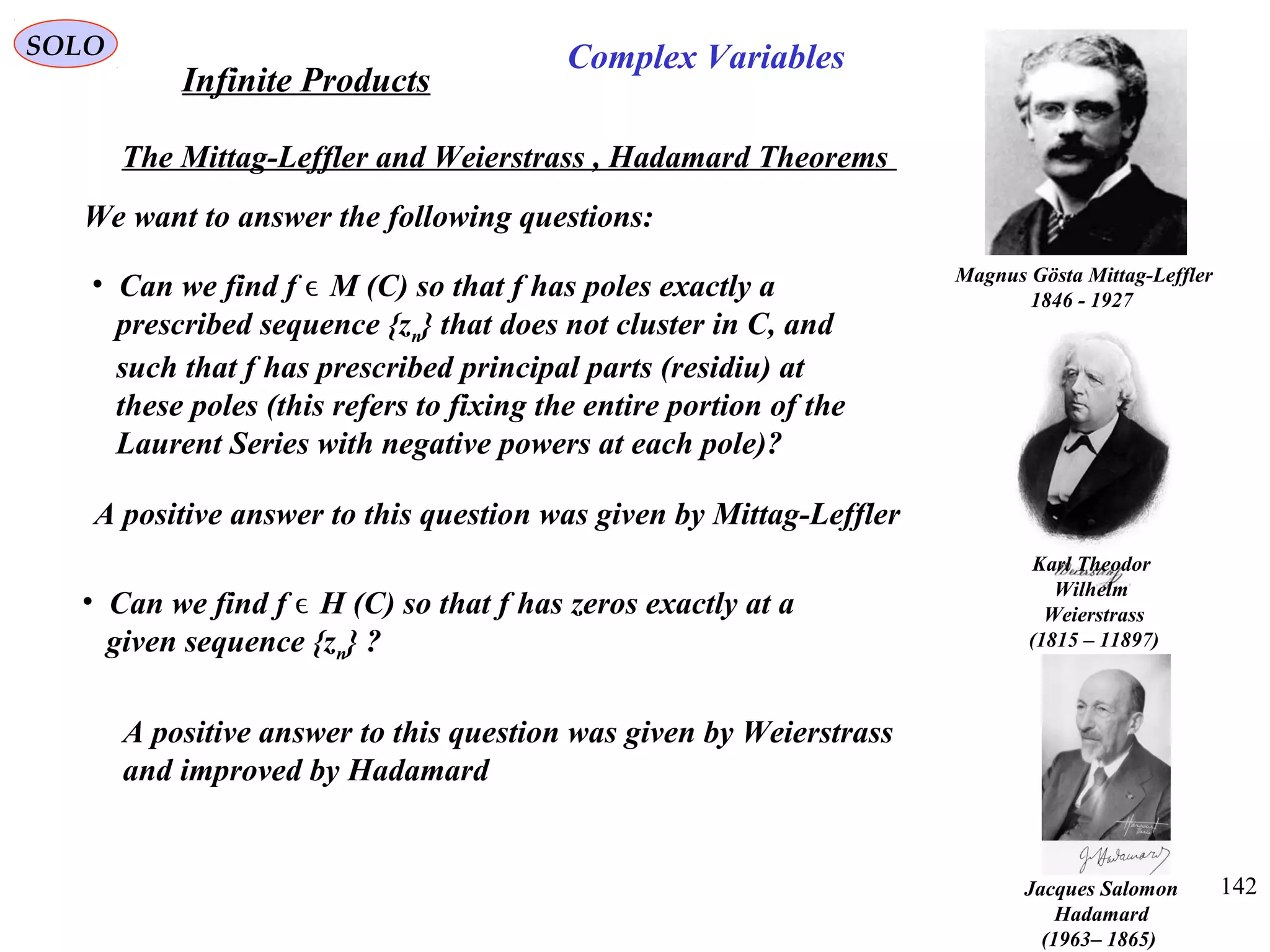

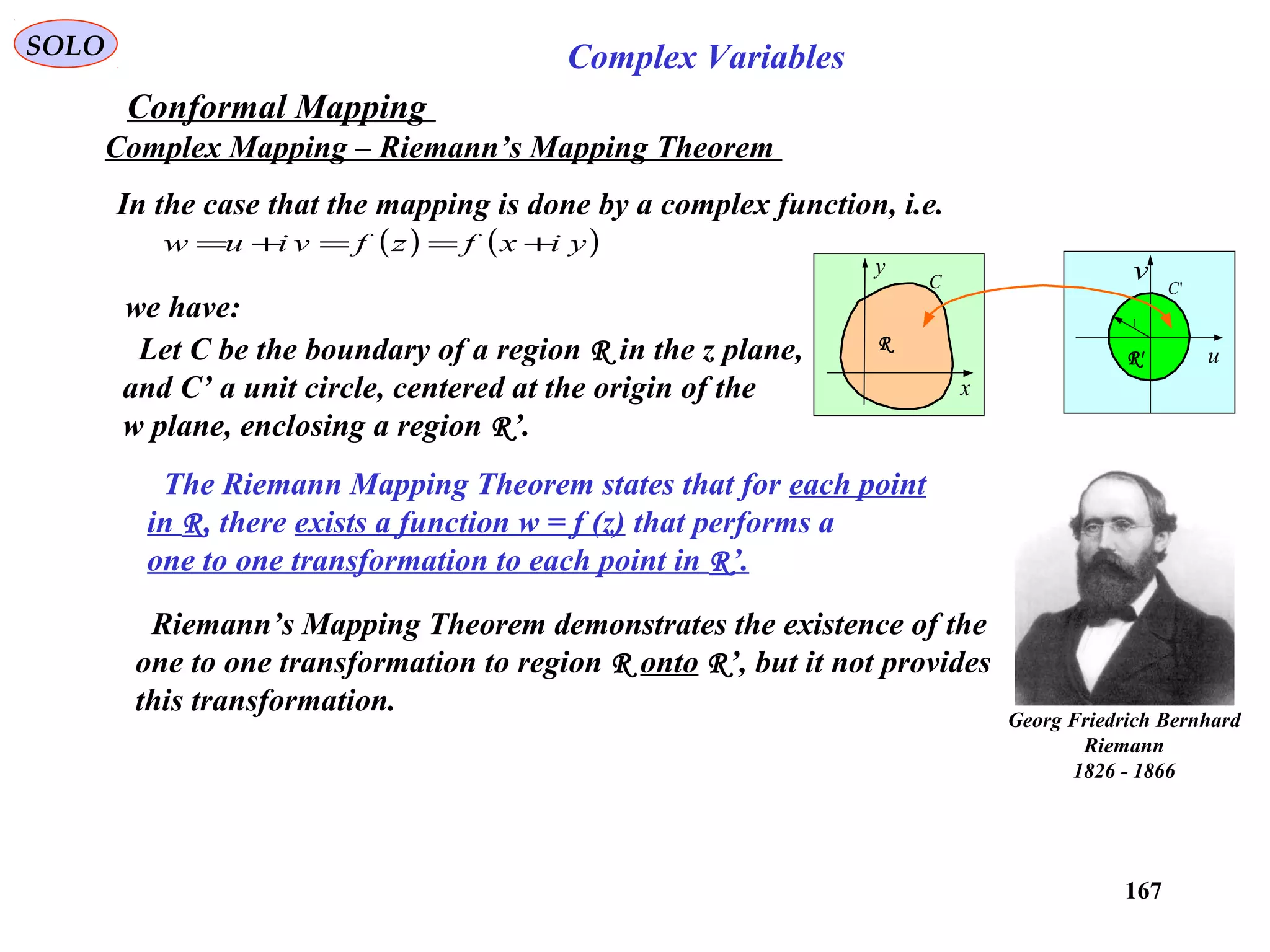

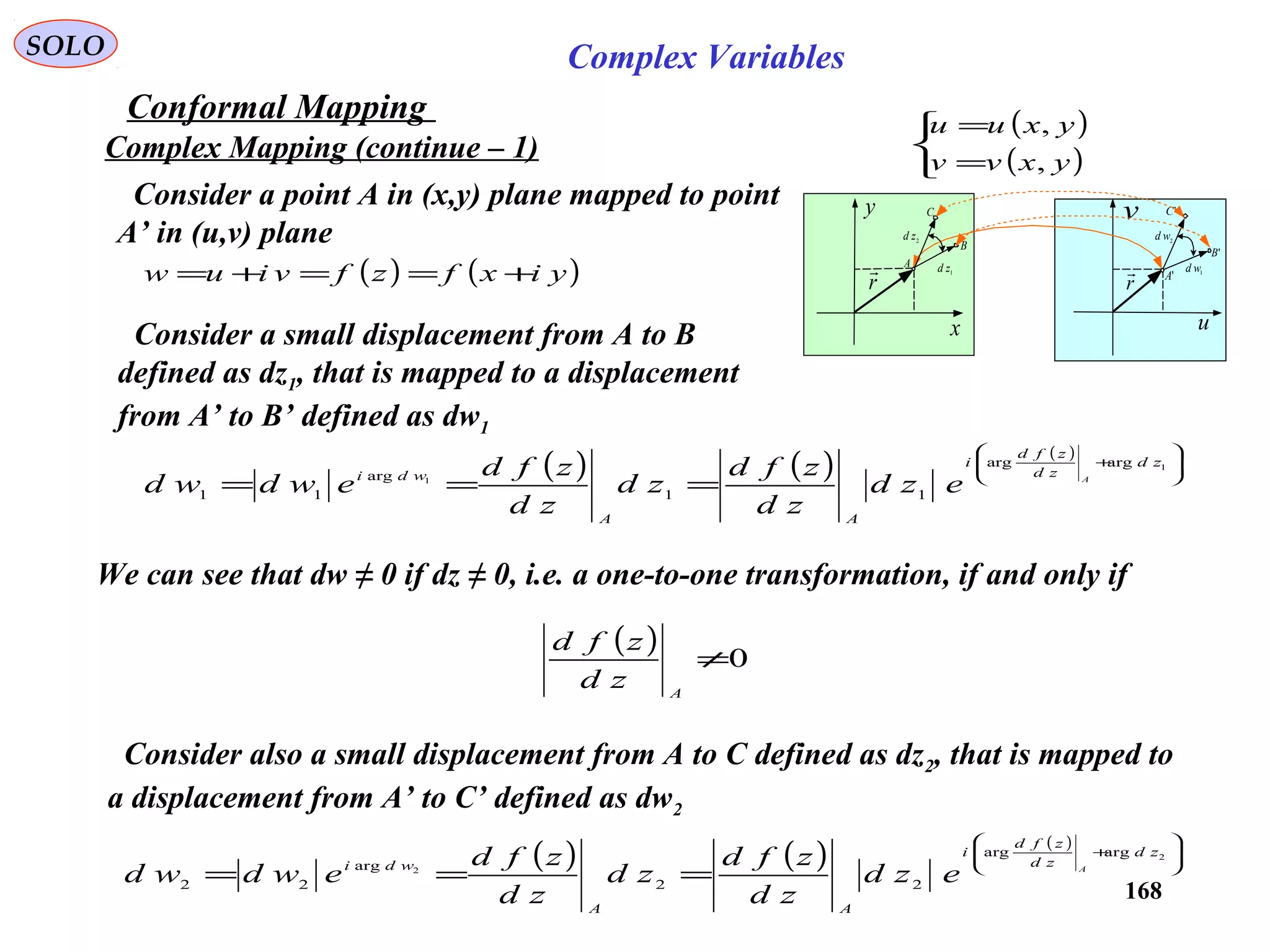

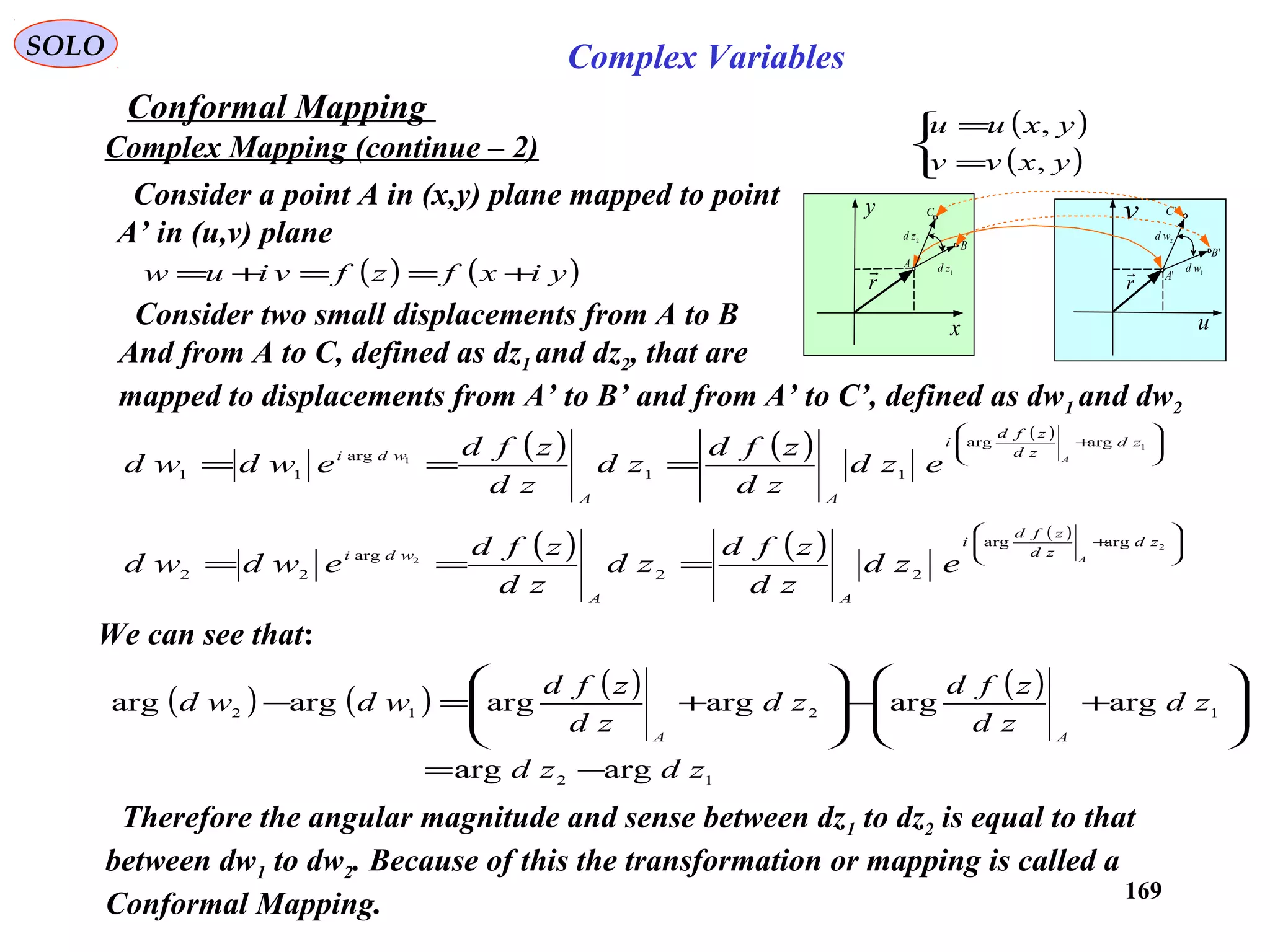

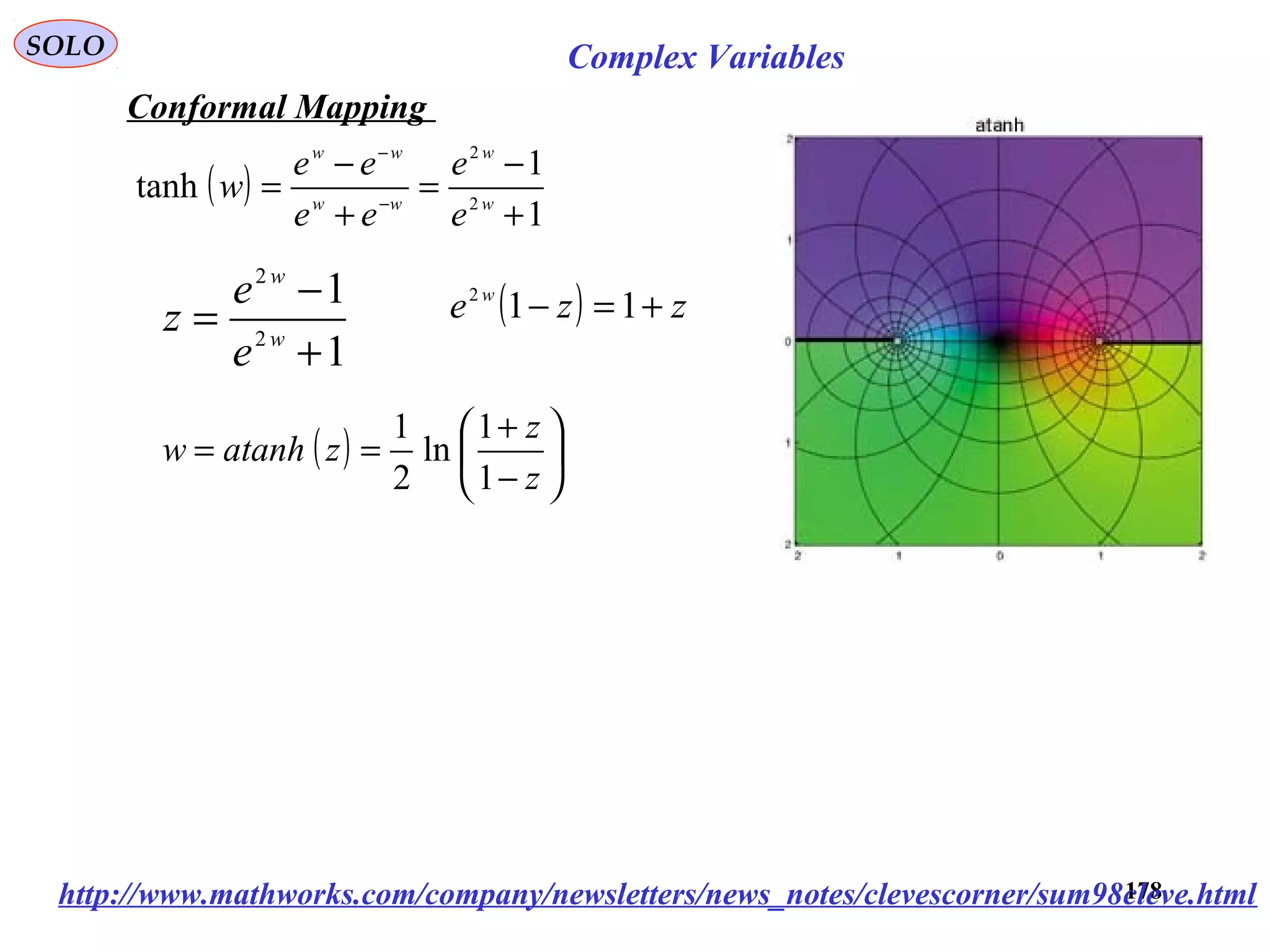

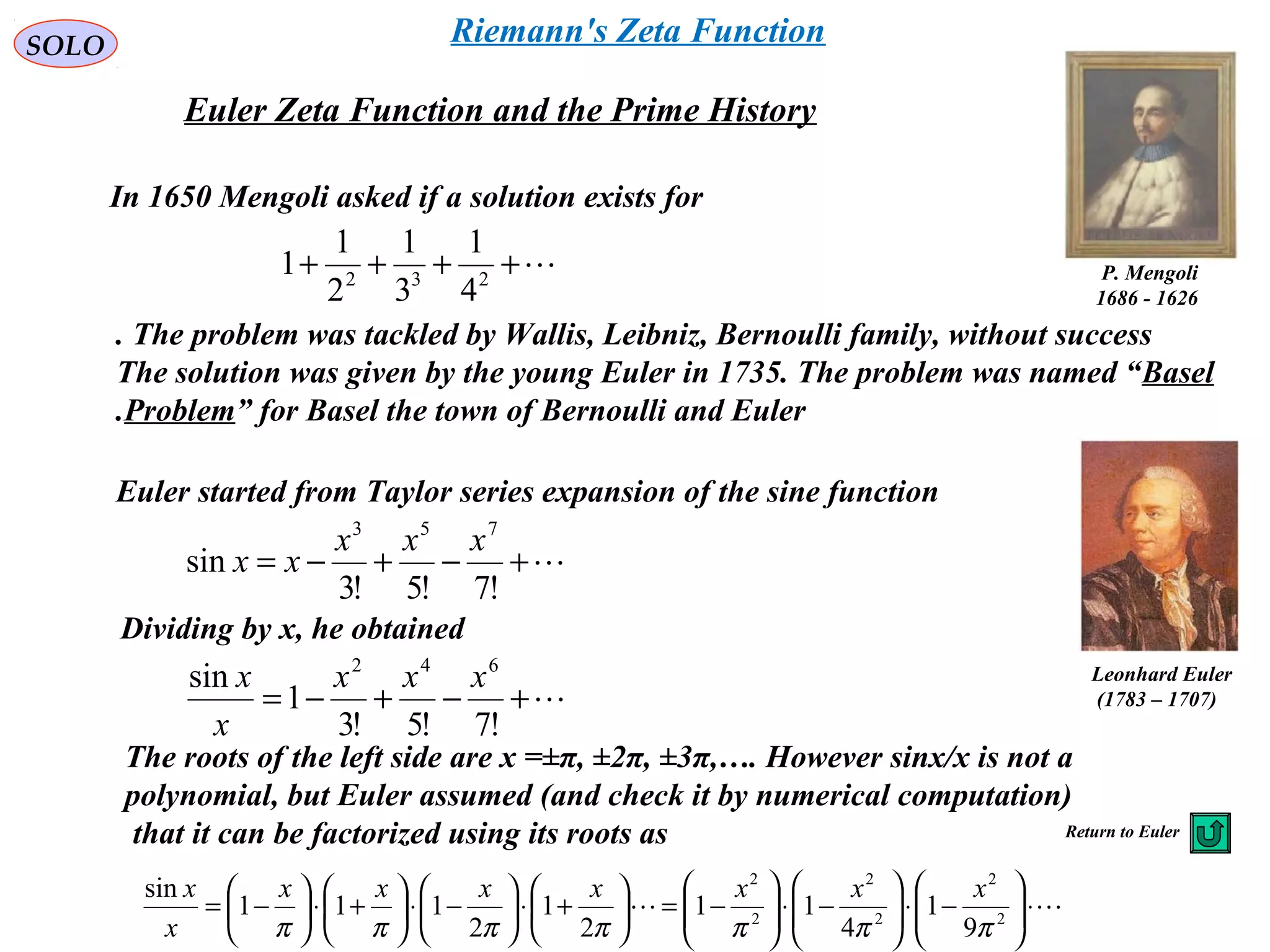

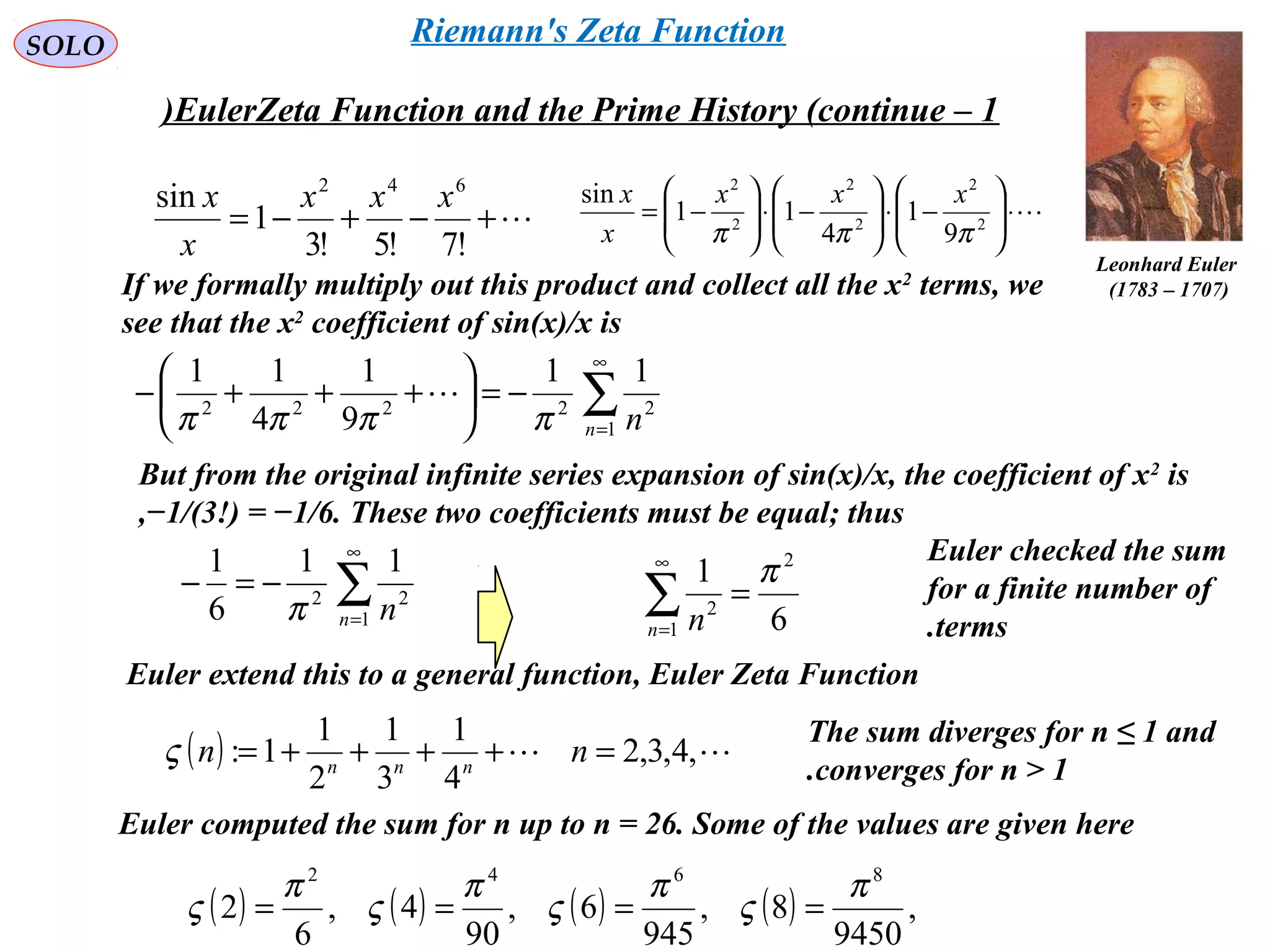

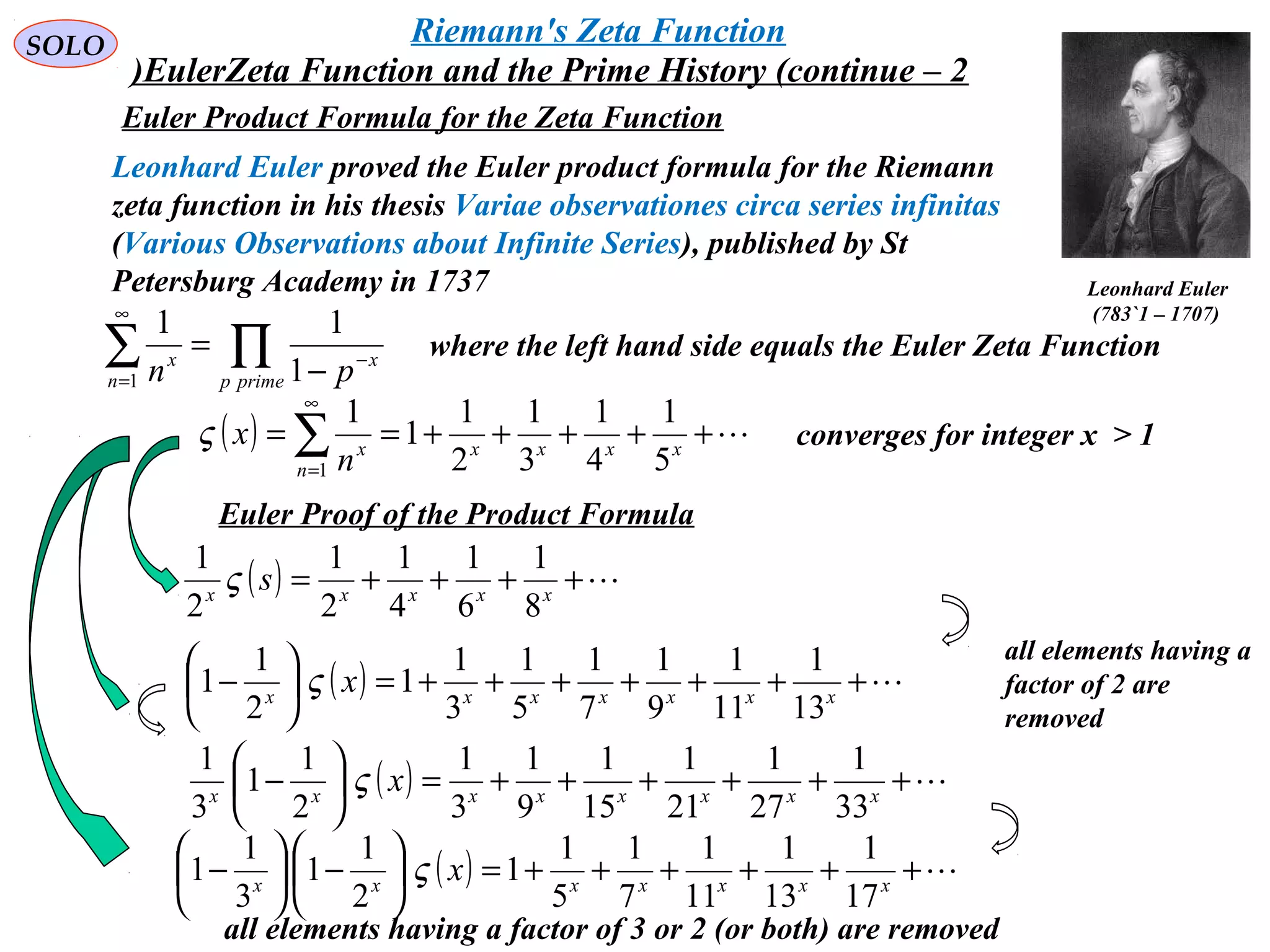

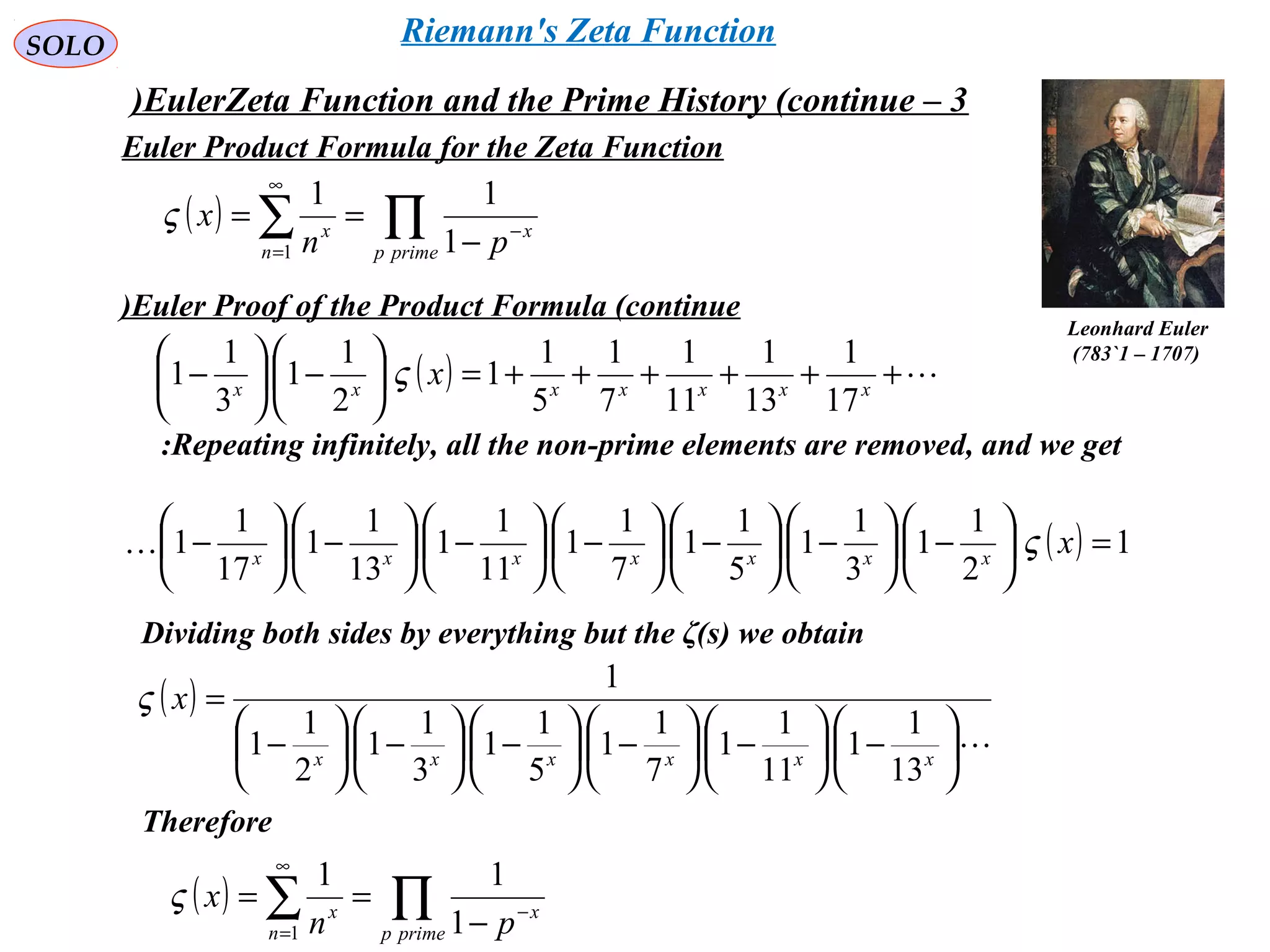

The document is a comprehensive overview of complex variables, covering fundamental definitions, operations, and the historical development of complex numbers. It includes detailed discussions on the axiomatic foundations, significant theorems, and key figures in the history of complex analysis. The document serves as a resource for understanding complex number systems, their properties, and their applications.

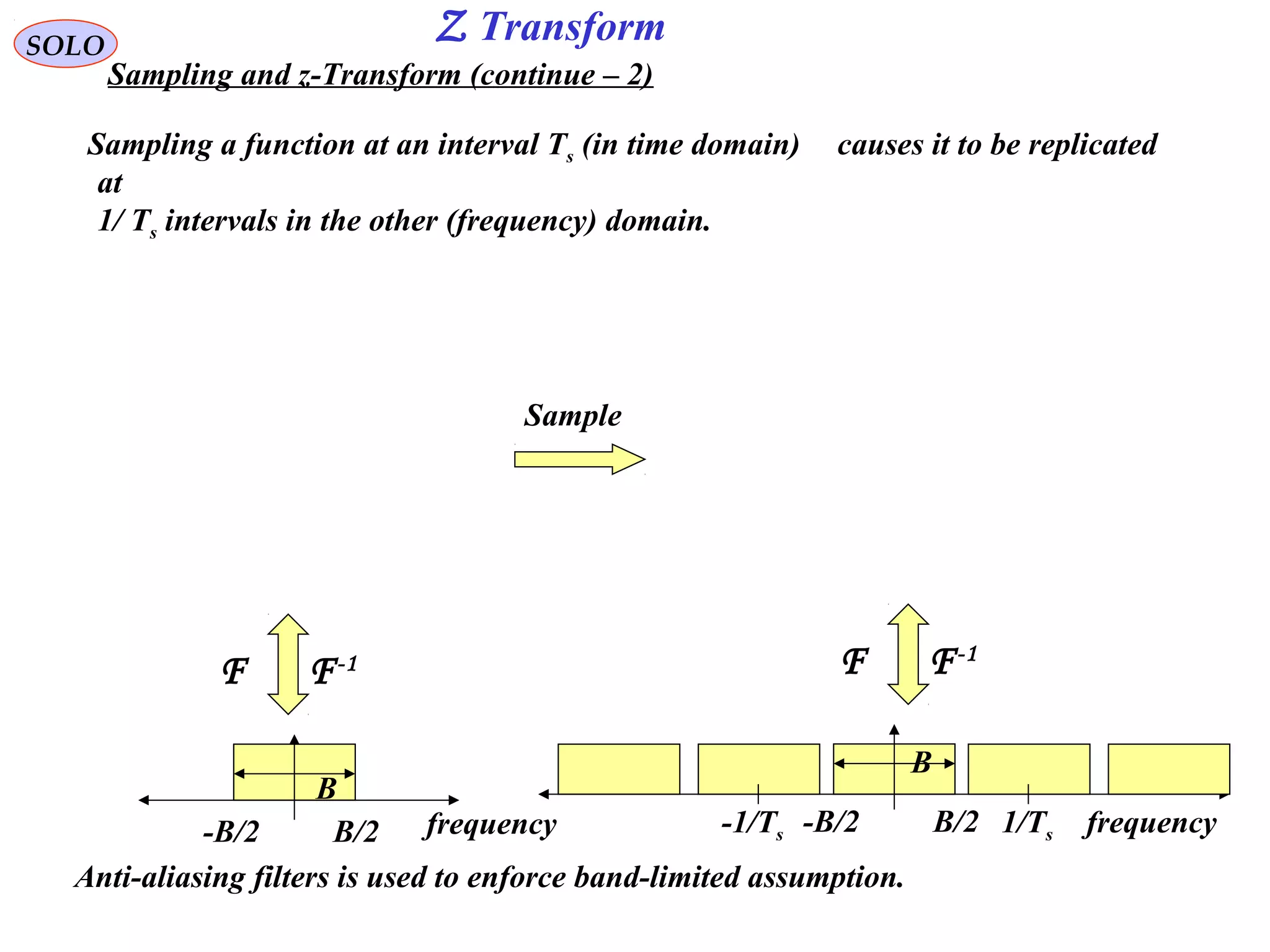

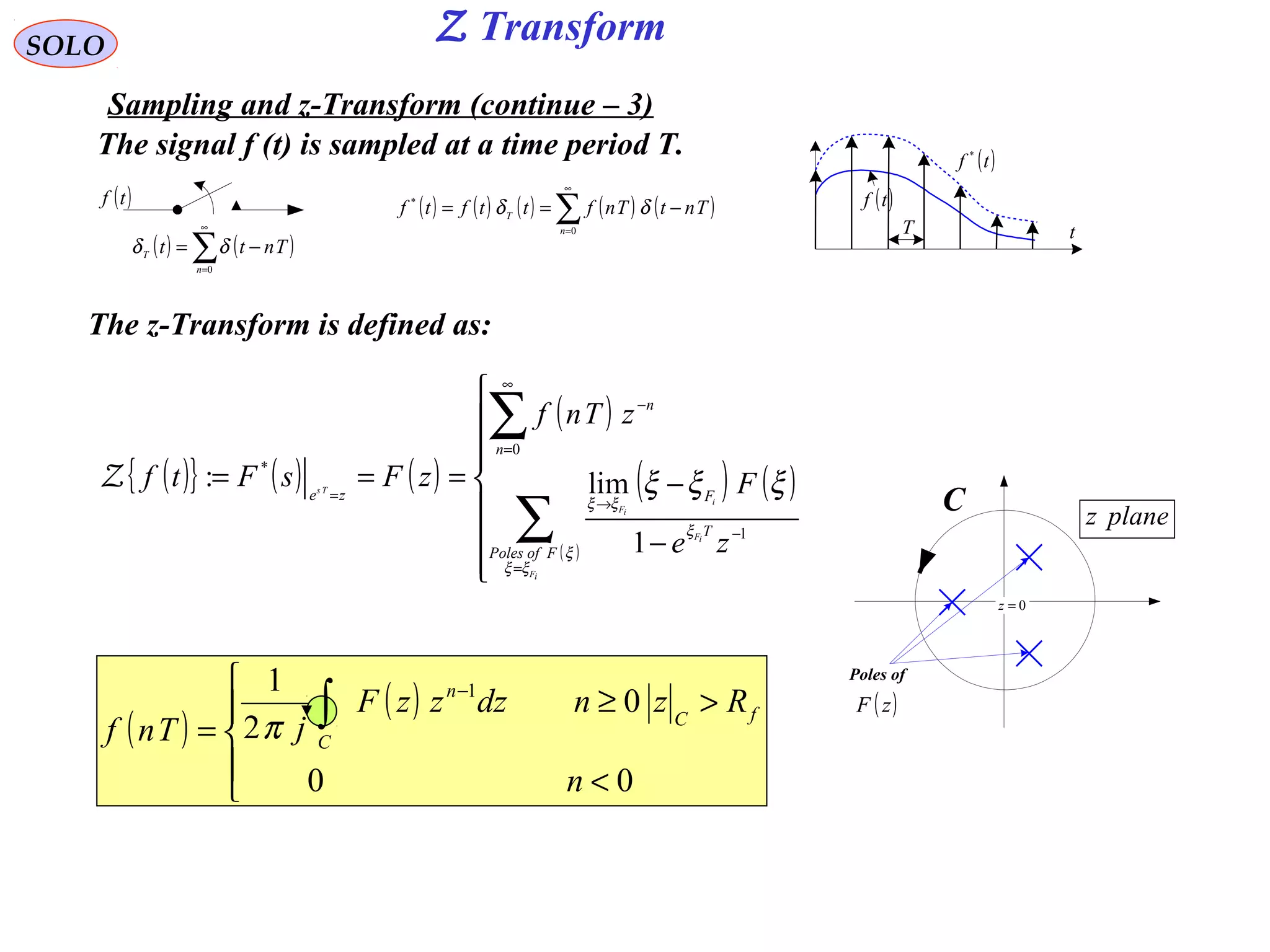

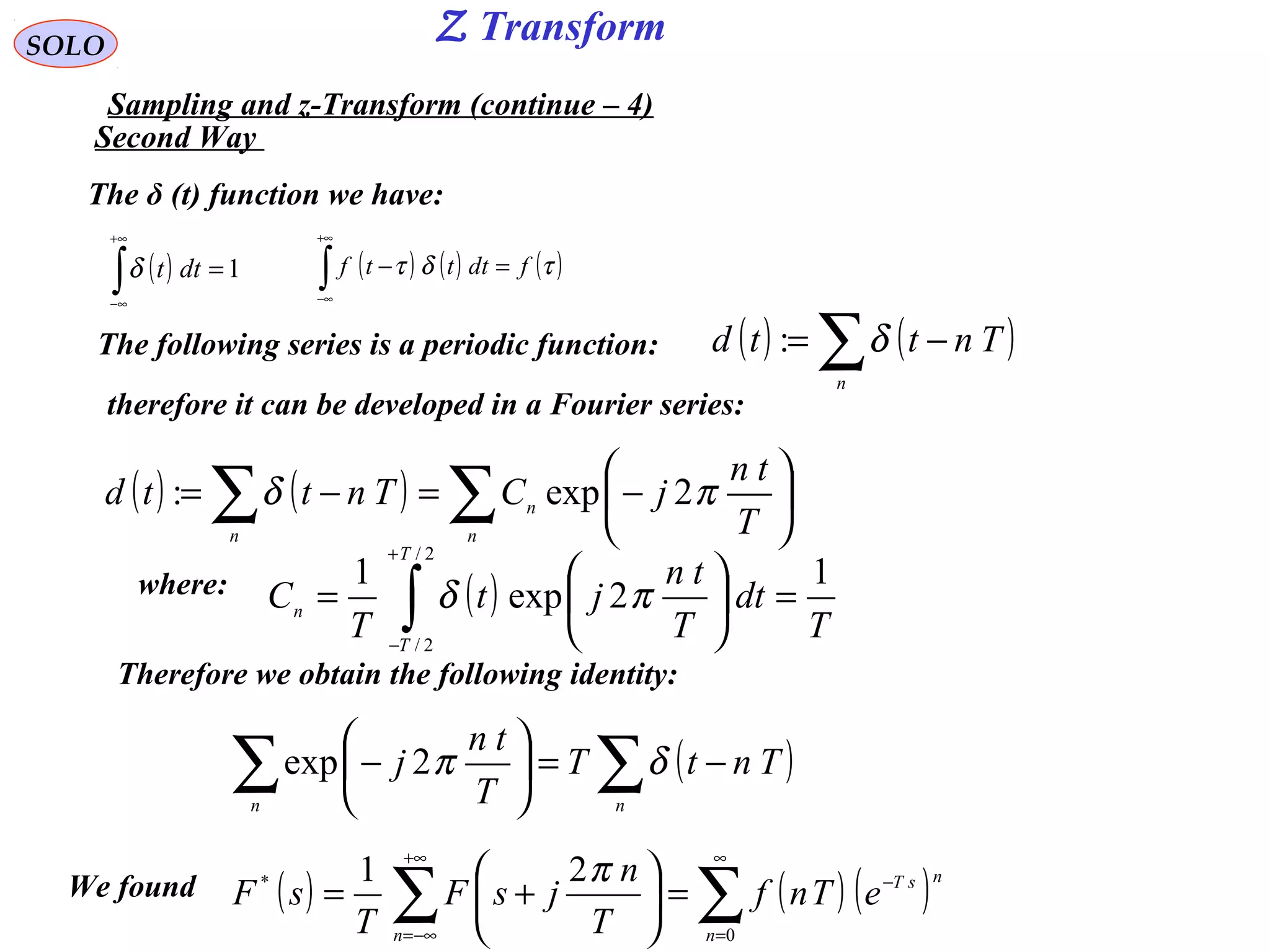

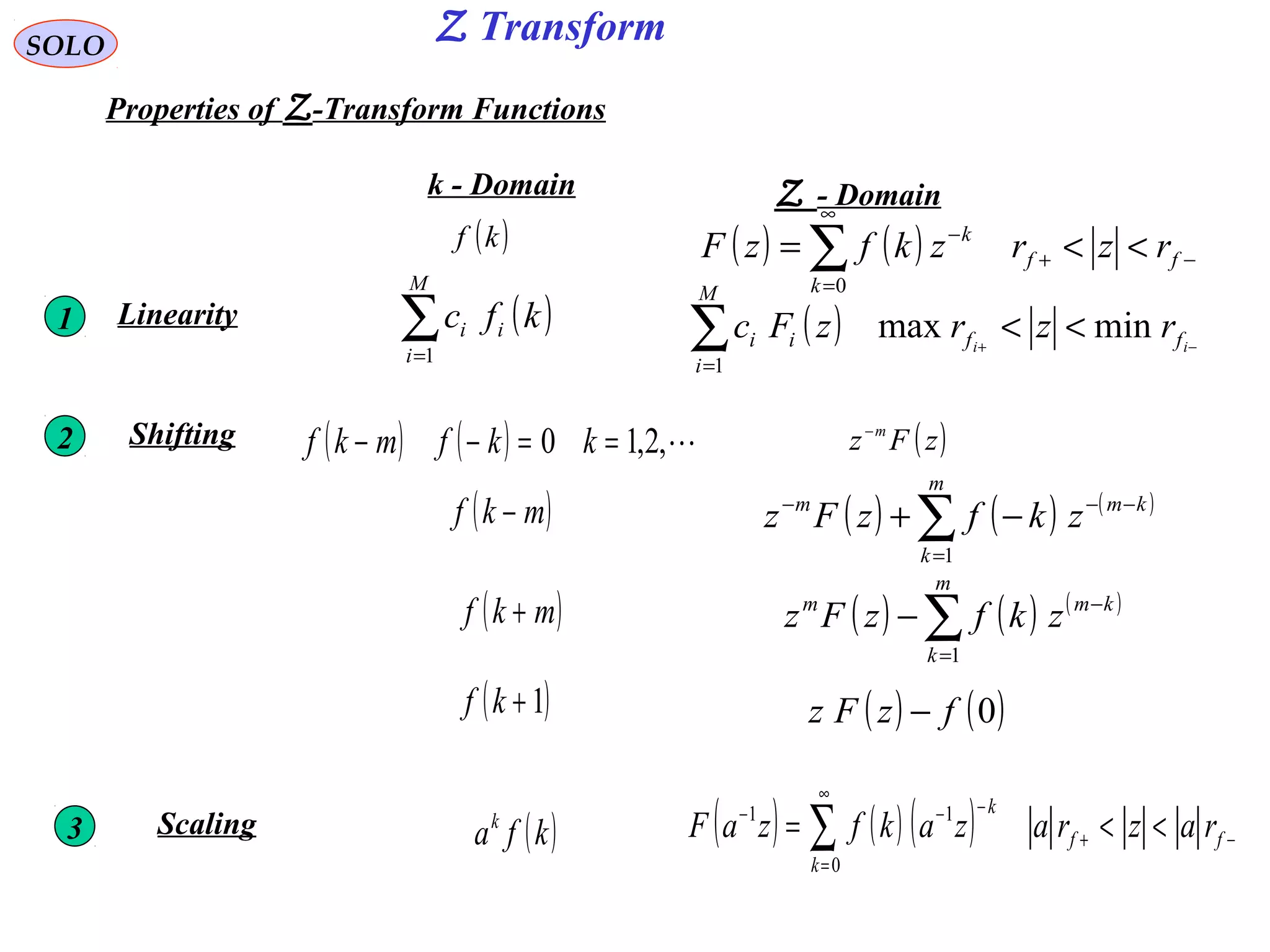

![12

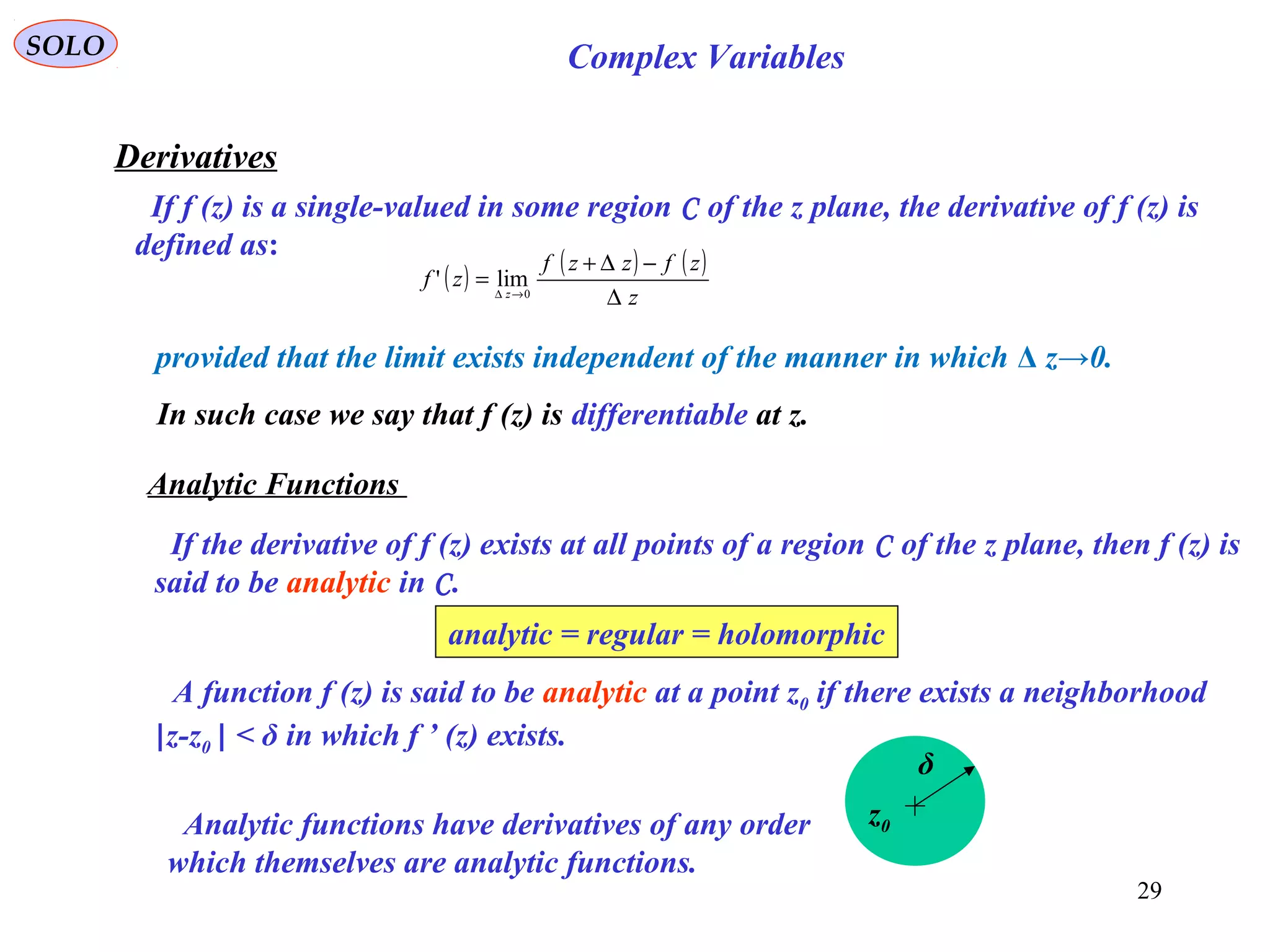

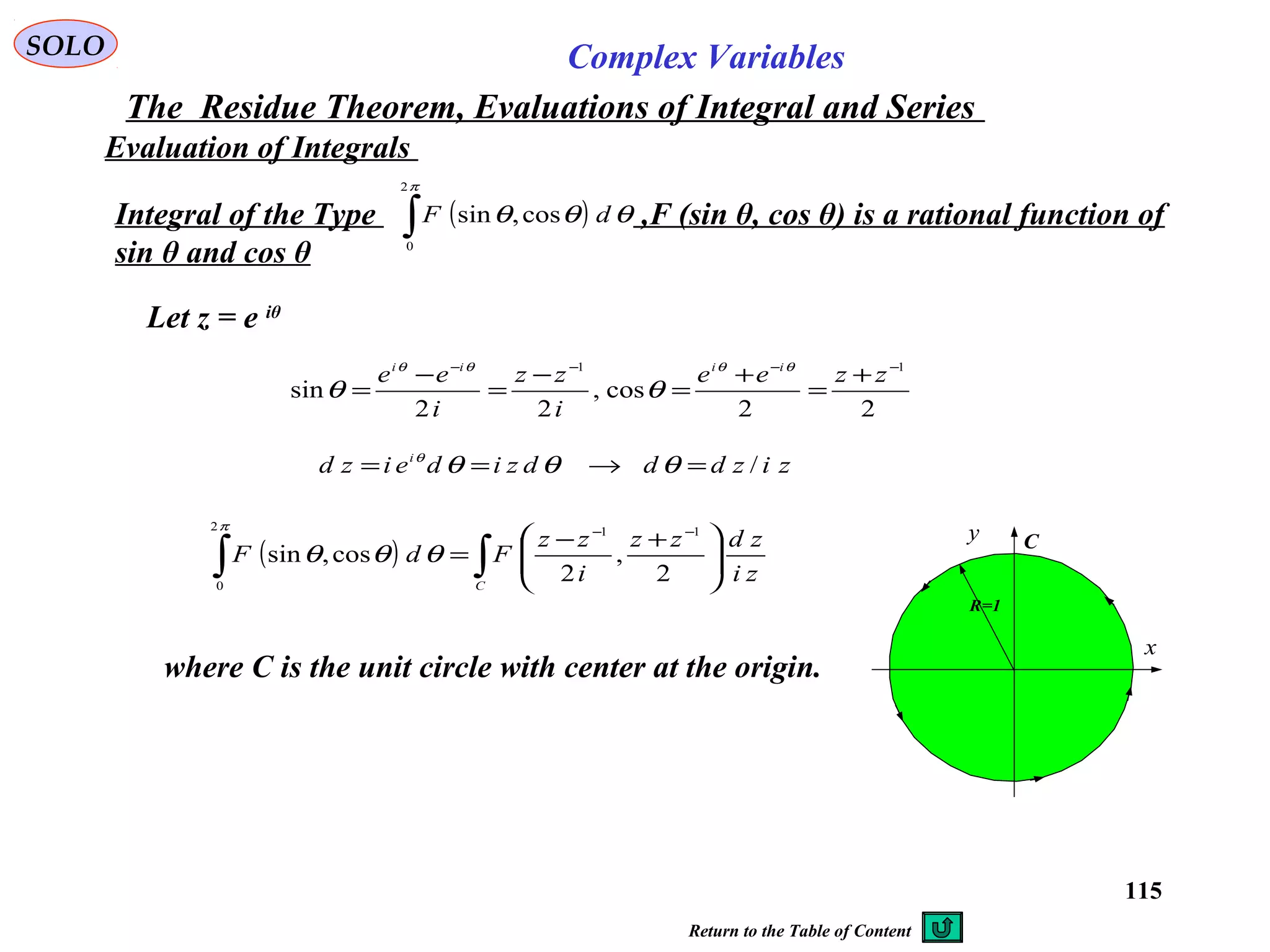

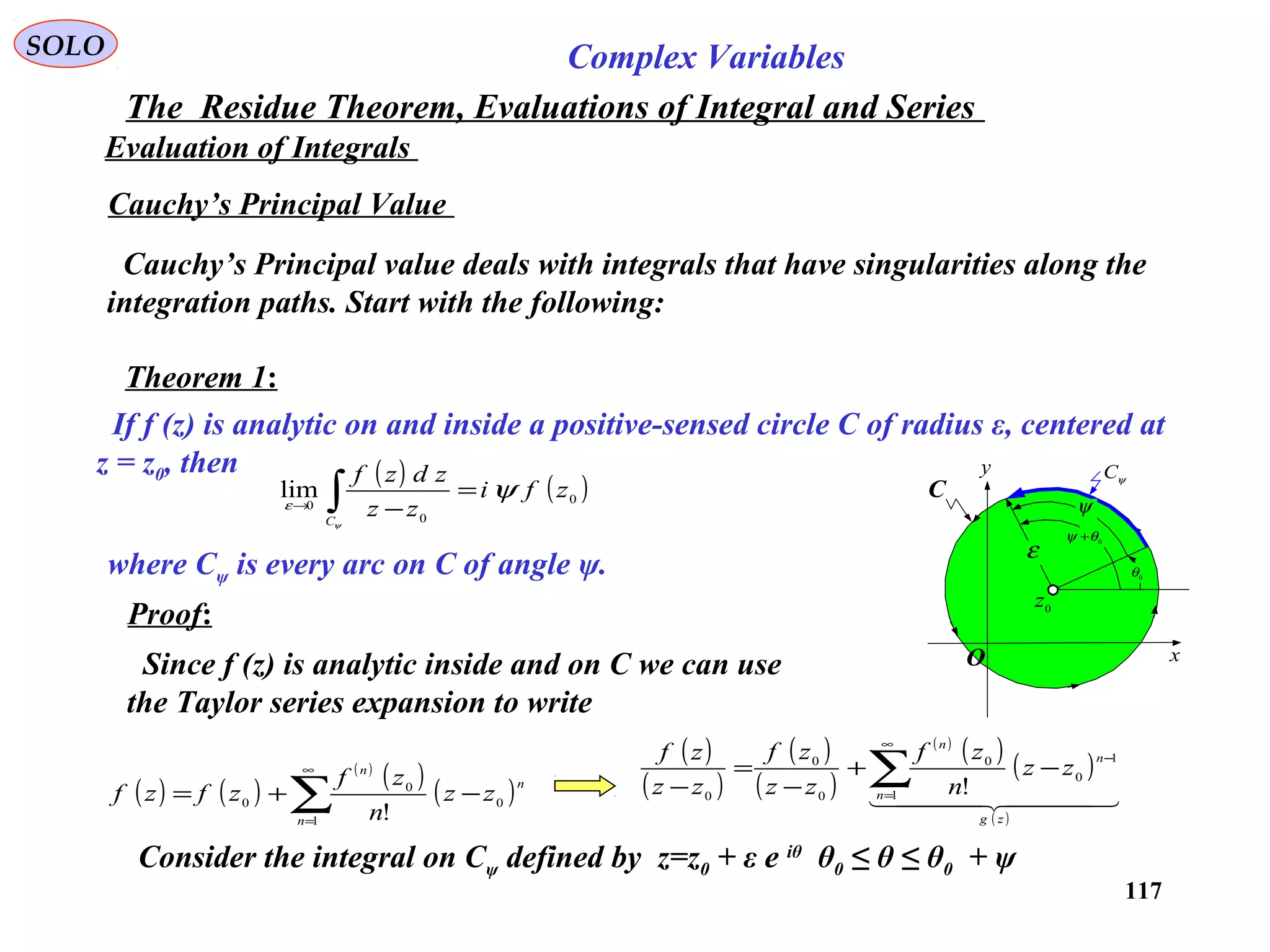

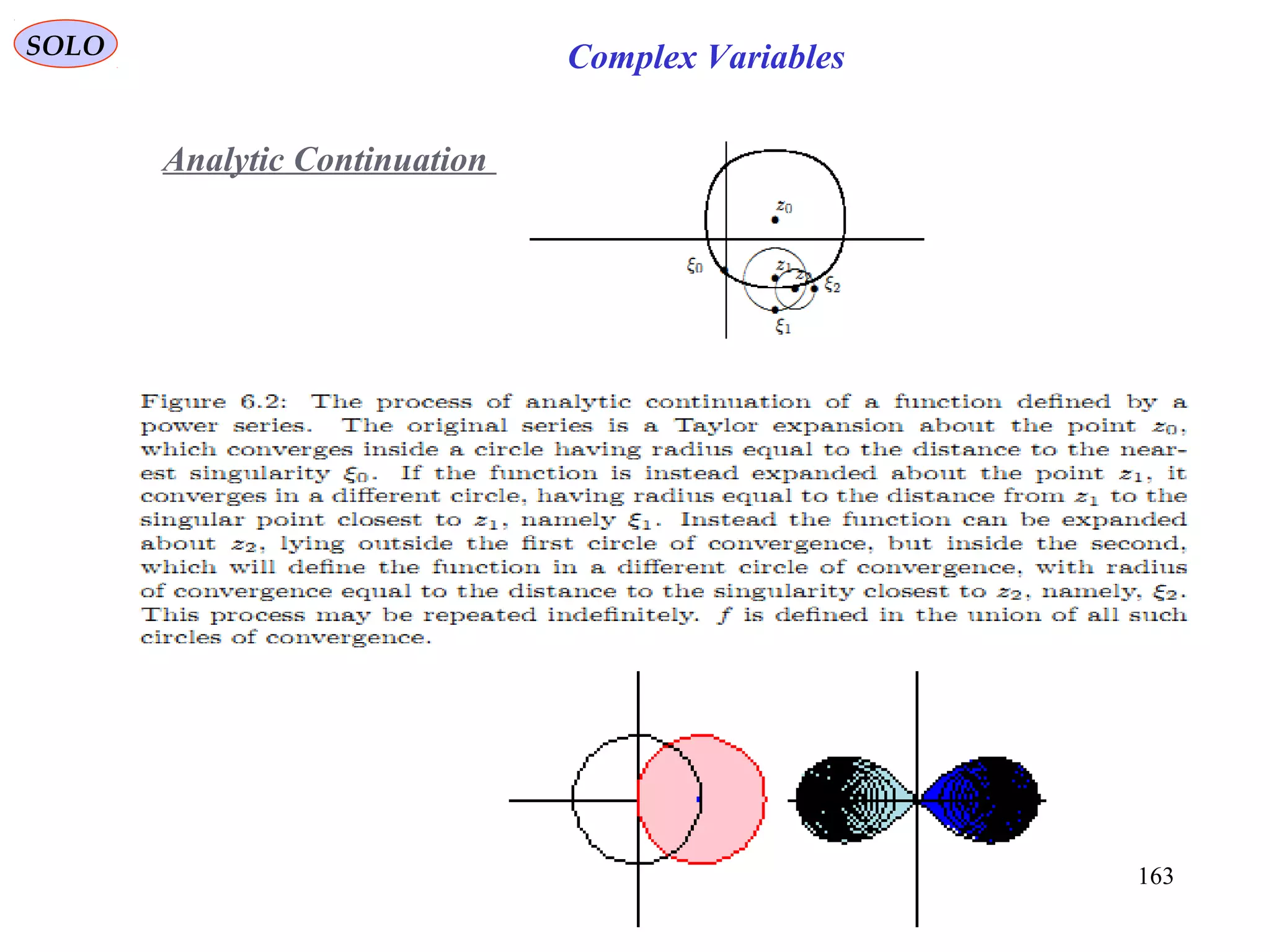

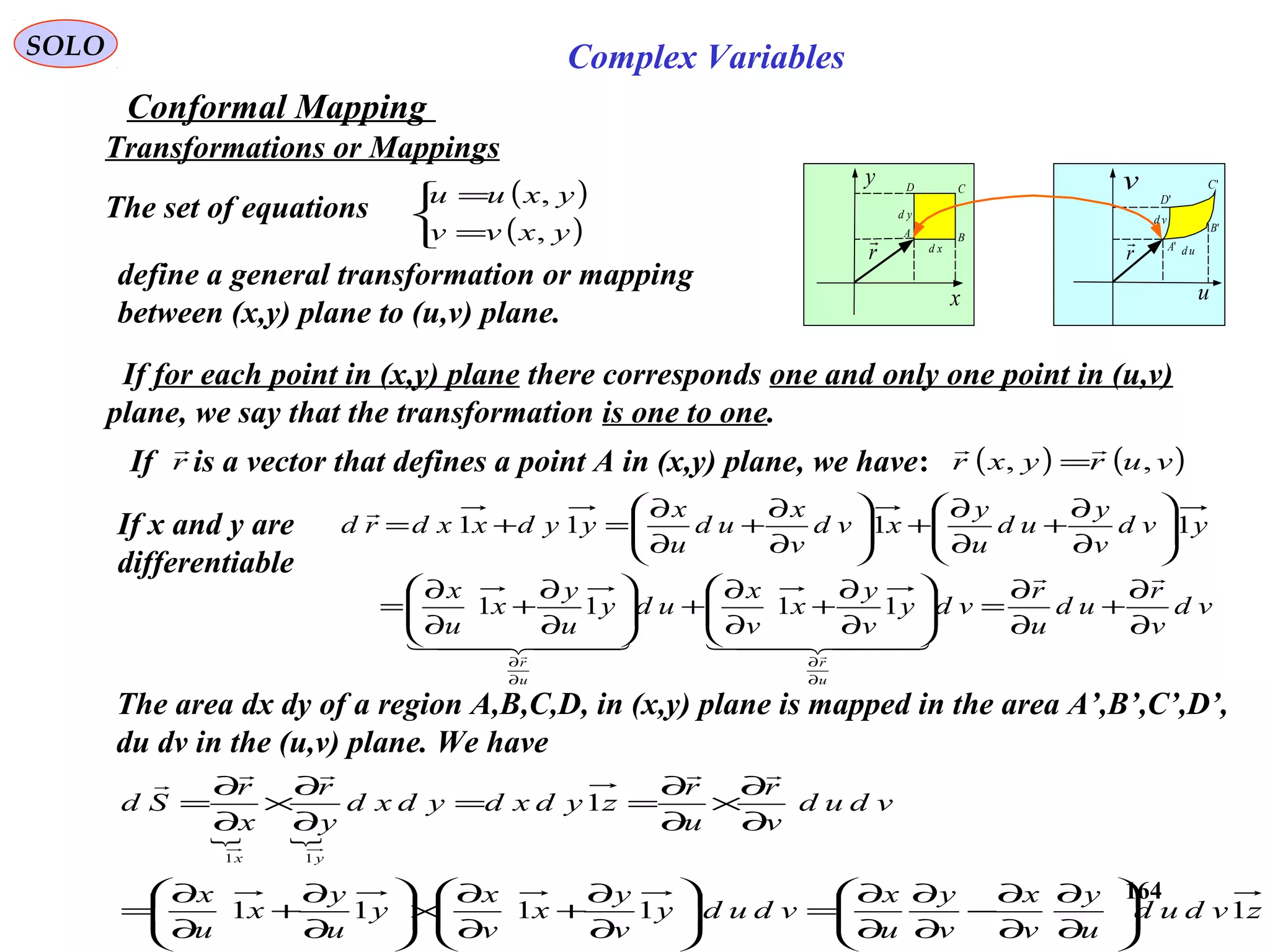

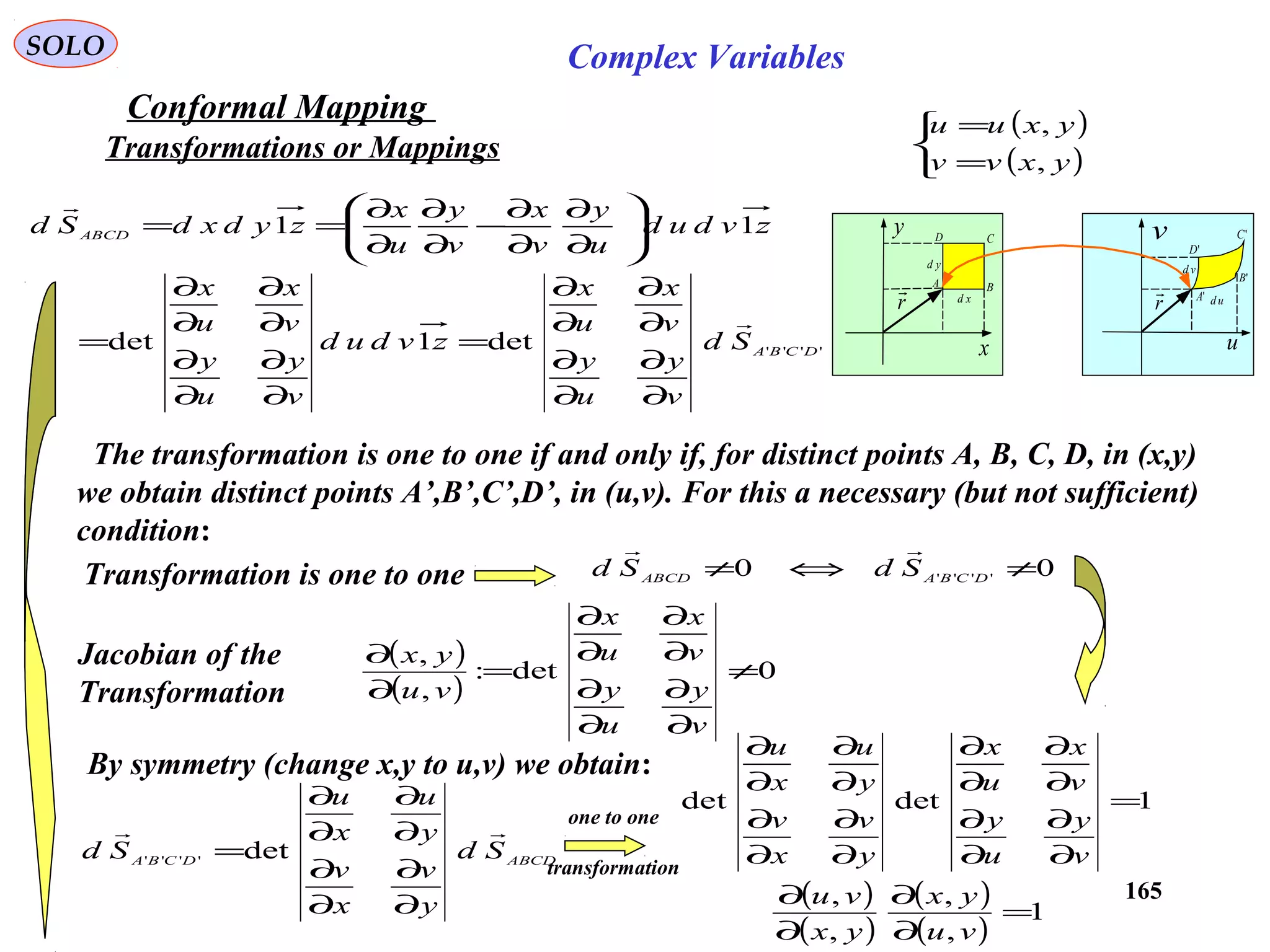

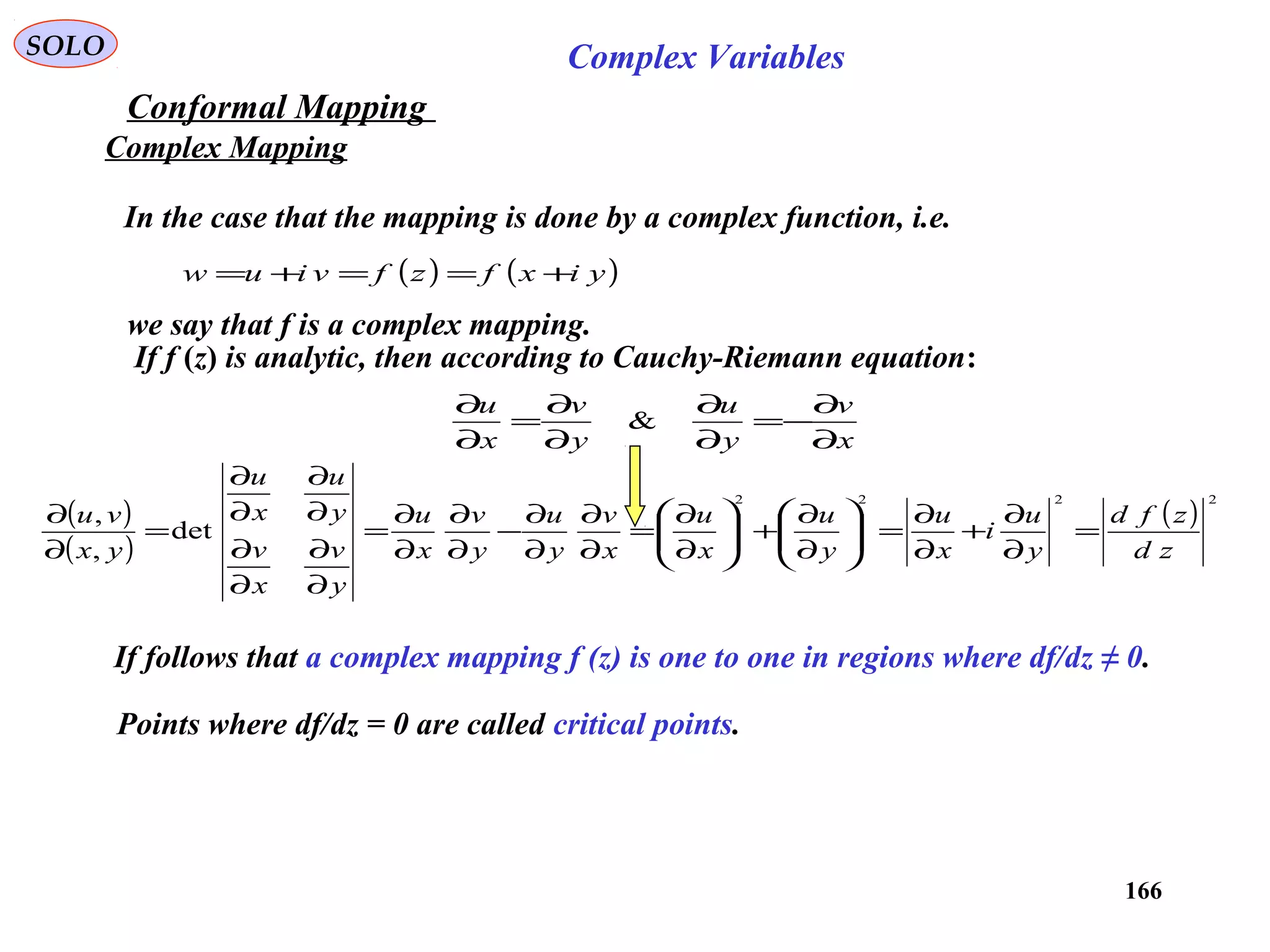

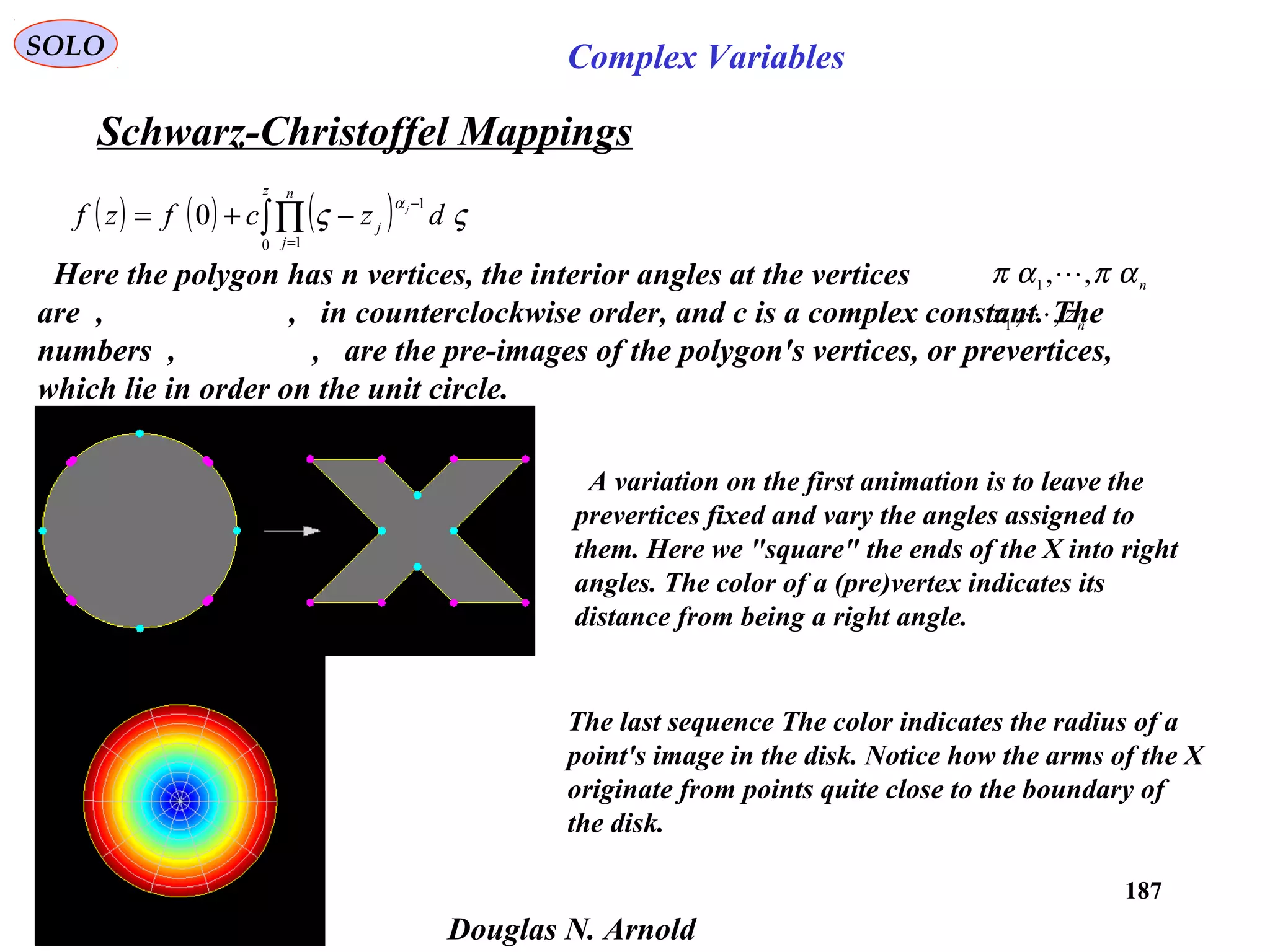

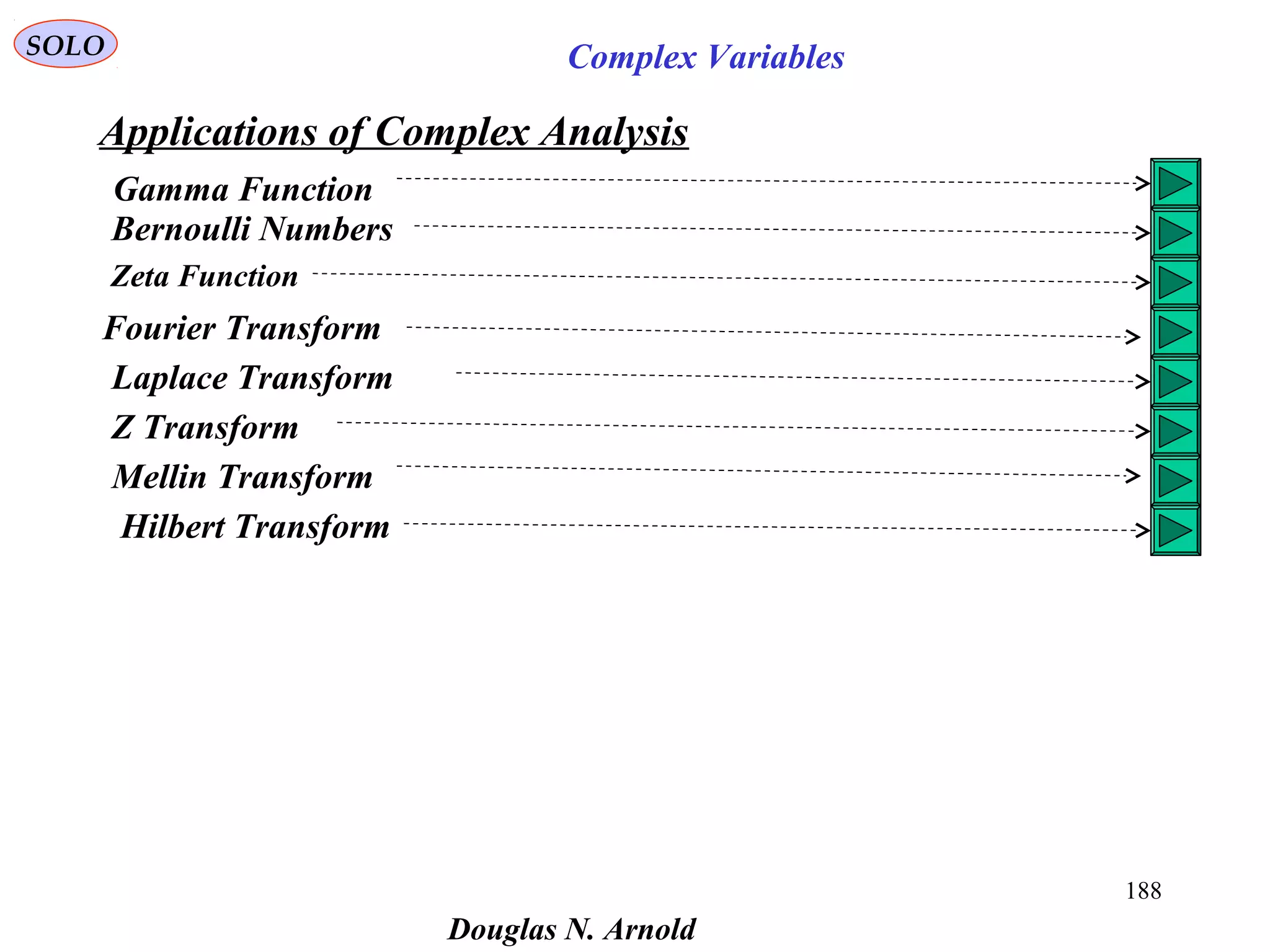

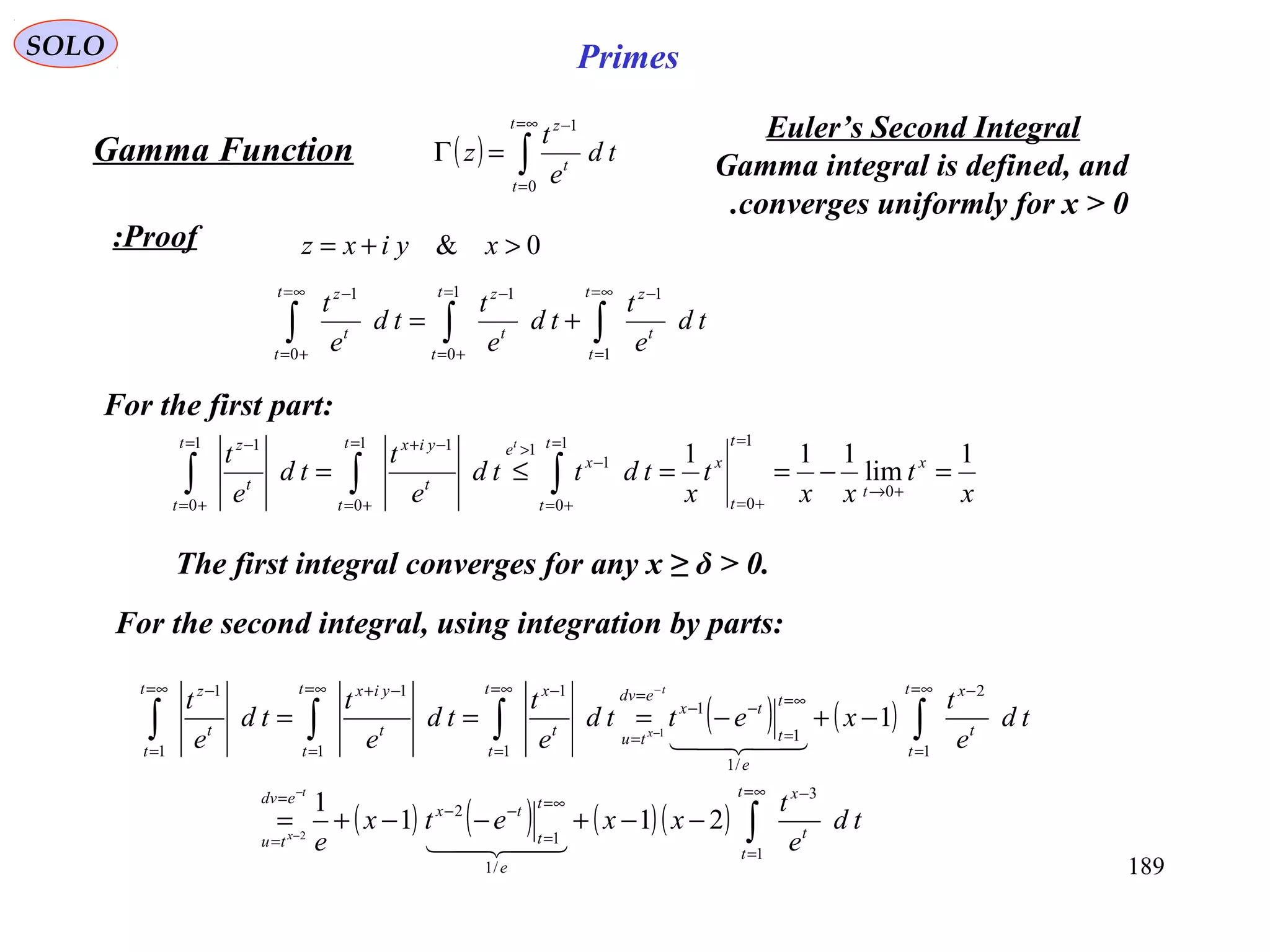

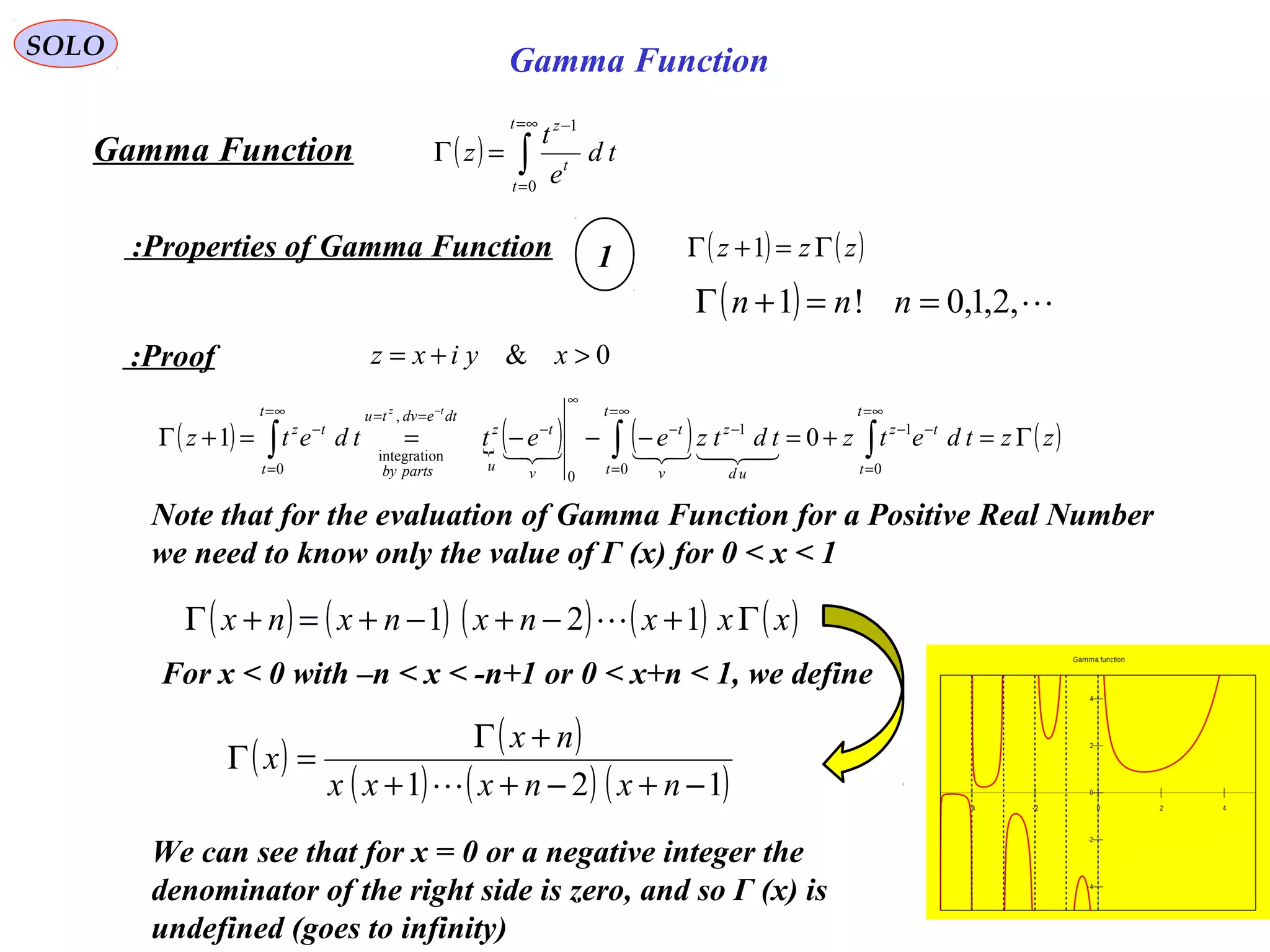

SOLO Complex Variables

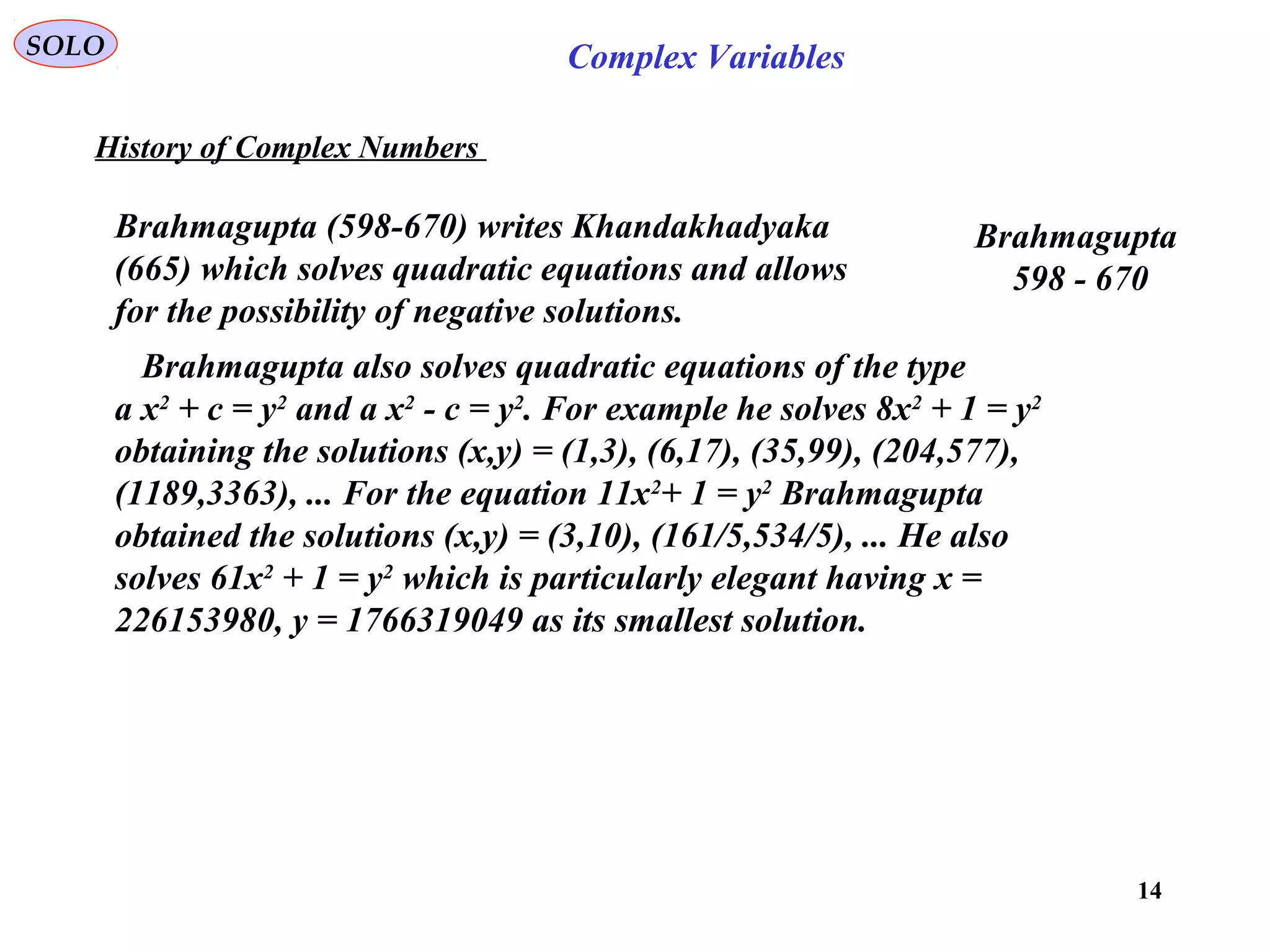

Fundamentals Operations with Complex Numbers z = x + i y

1

,

, 2

−=

==

==+

= i

ArgumentModuluse

partImaginaryypartRealxyix

z i

θρρ θ

θ

ρ i

eyixz =+=

y

x

ρ

θ

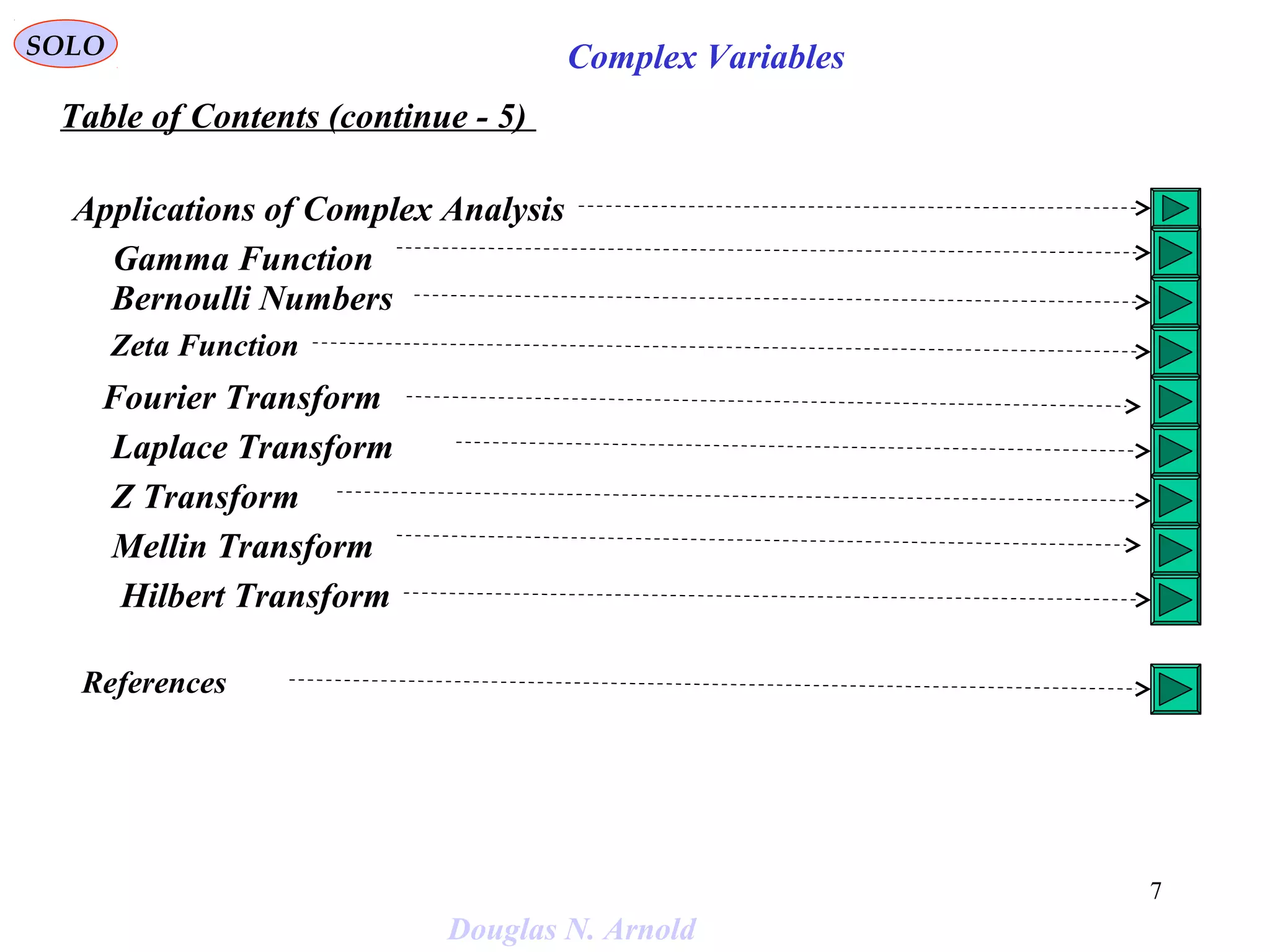

Polar Form of a Complex Number θ

ρ i

eyixz =+=:

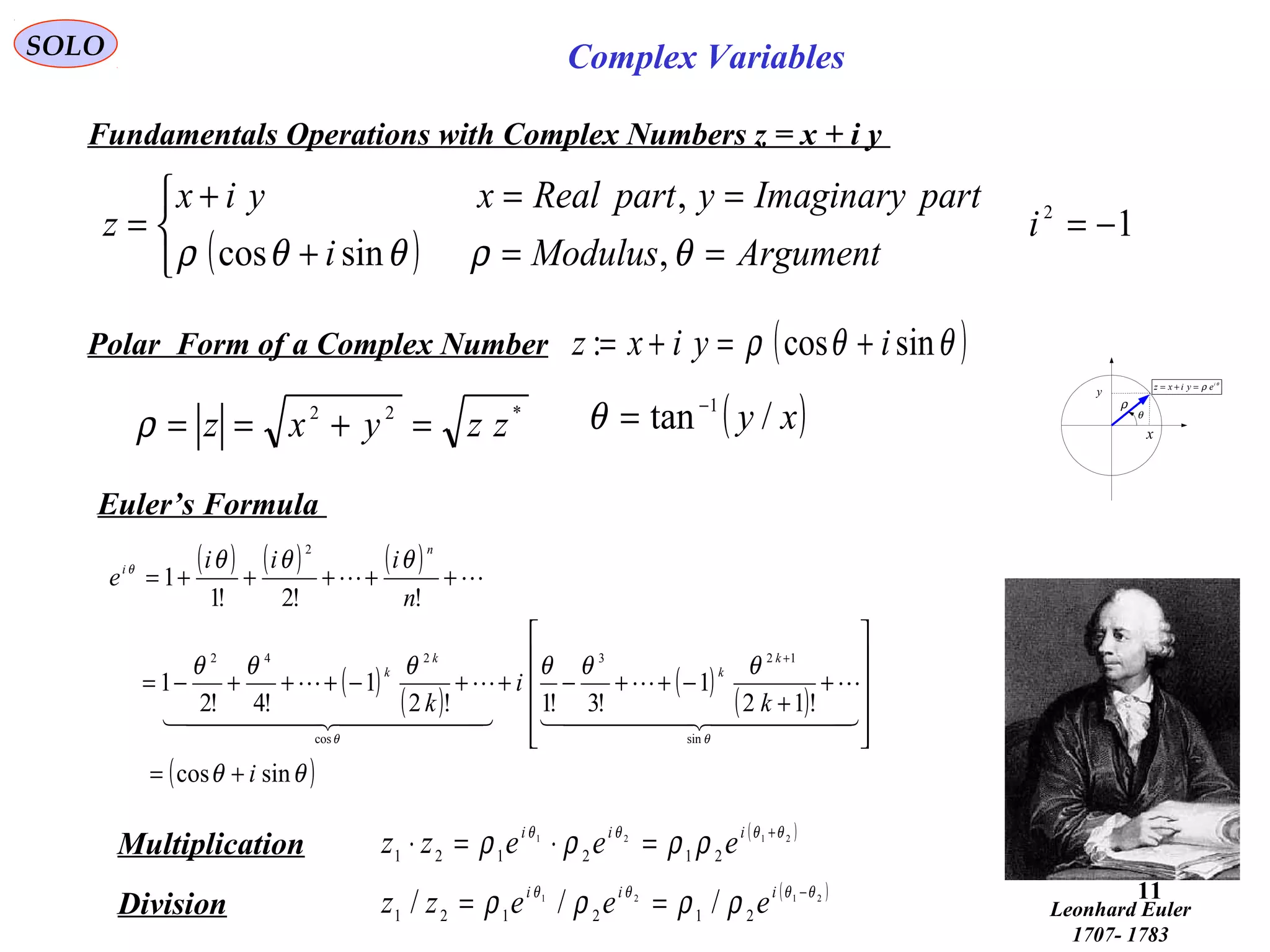

De Moivre Theorem

( )[ ] ( )

( )θθρρ

ρθθρ

θ

θ

nine

eiz

nnin

ninn

sincos

sincos

+==

=+=

Roots of a Complex Number

[ ]

( ) ( )[ ]

1.2.1.0

2

sin

2

cos

sincos

/1

/1/12/1

−=

+

+

+

=

+== +

nk

n

k

i

n

k

iez

n

nnkin

πθπθ

ρ

θθρρ πθ

πki

ez 25

1==

y

x

5

2

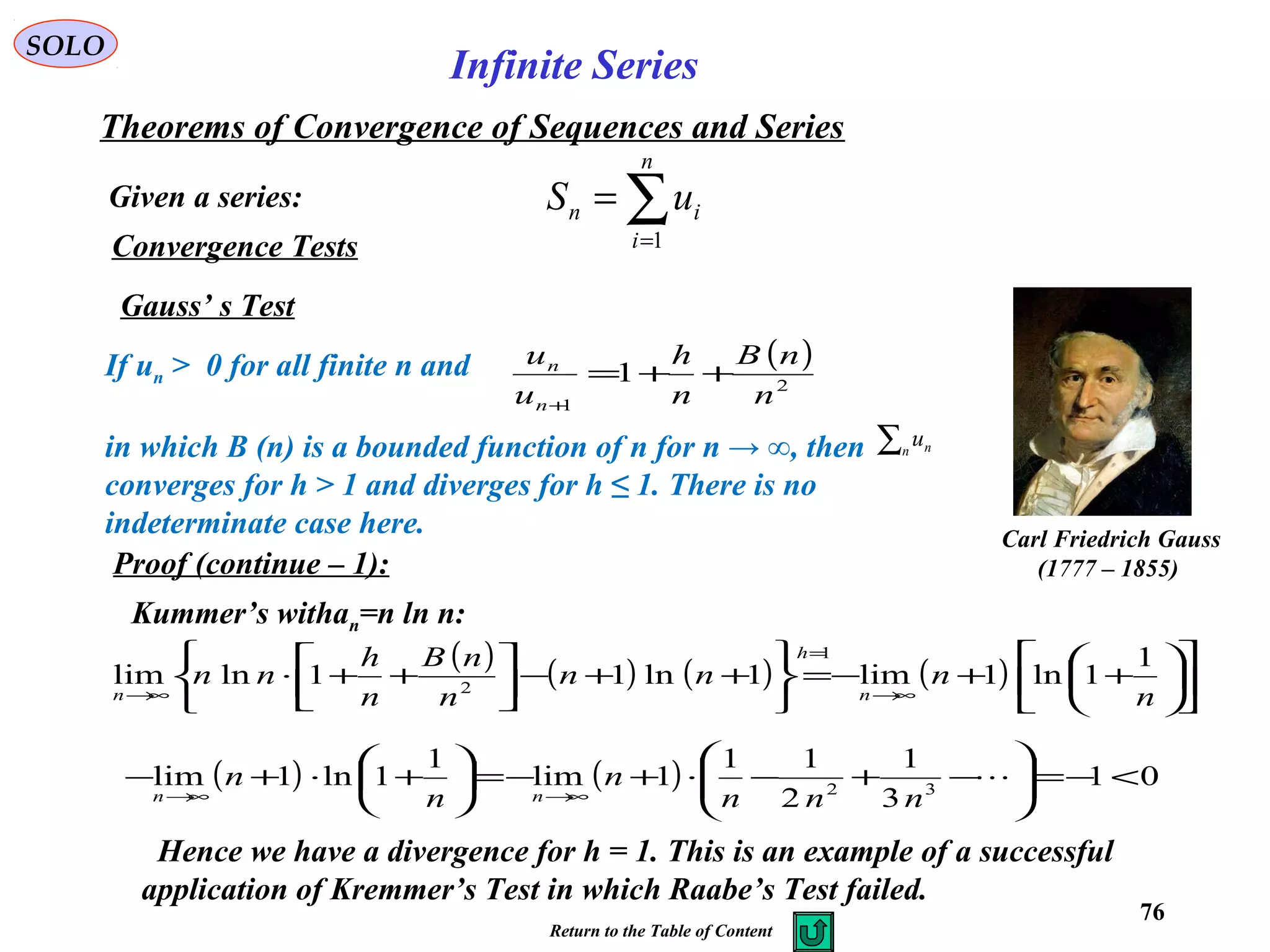

2

π

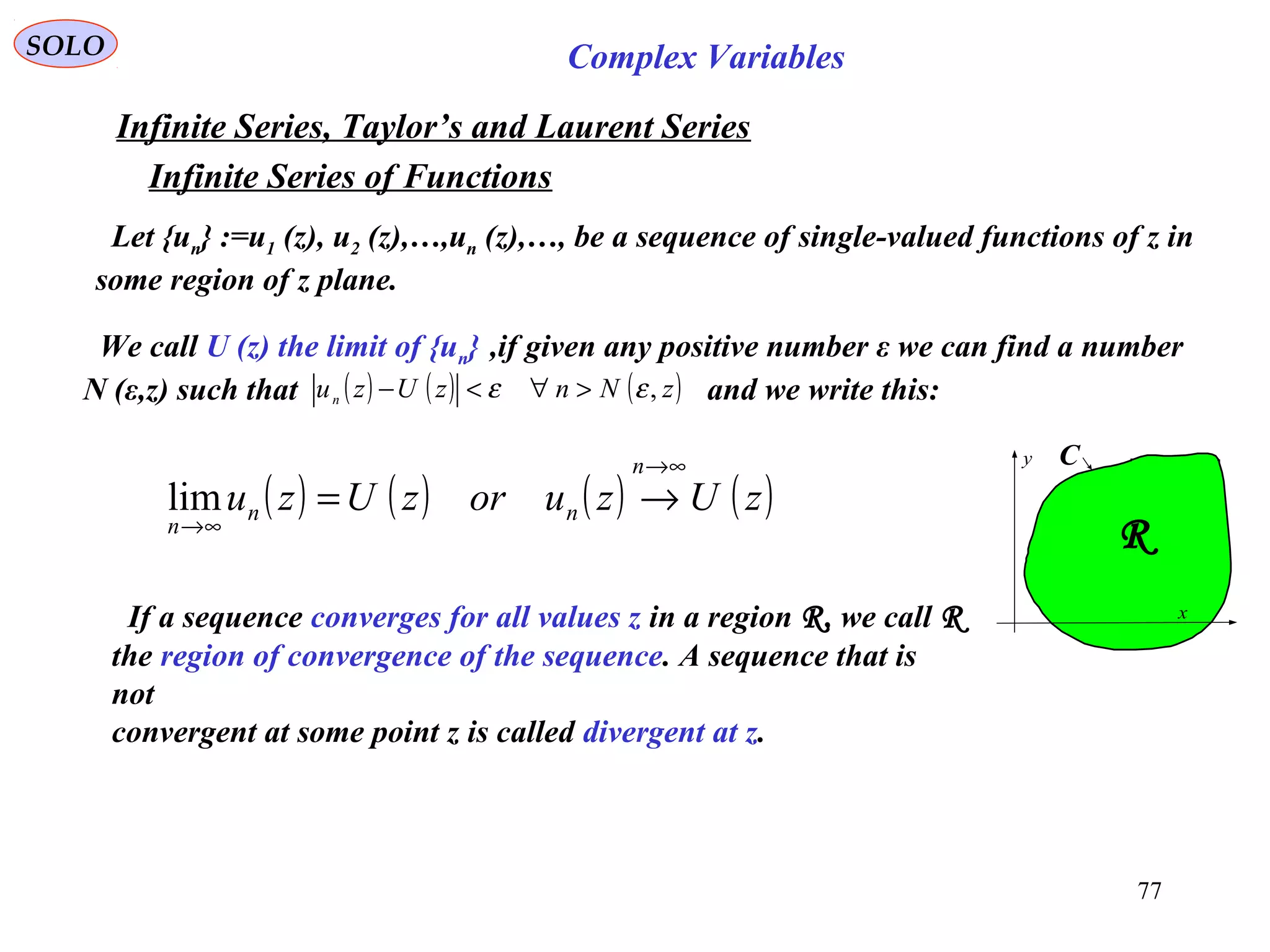

i

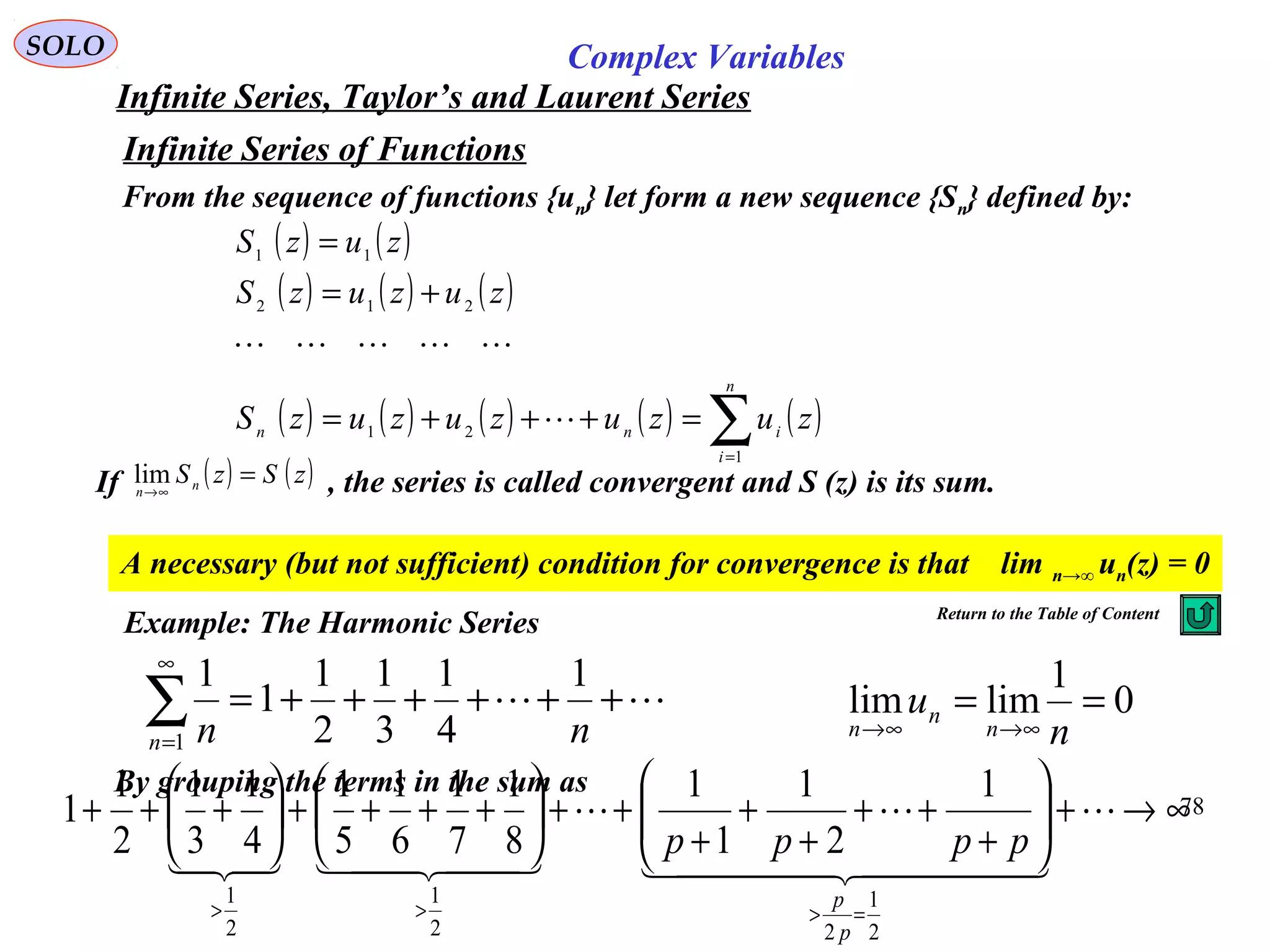

ez =

5

2

2

2

π

i

ez =

5

2

3

3

π

i

ez =

5

2

4

4

π

i

ez =

11

=z

72

72

72

72

72

Abraham De Moivre

1667 - 1754

Return to Table of Contents](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-12-2048.jpg)

![15

SOLO Complex Variables

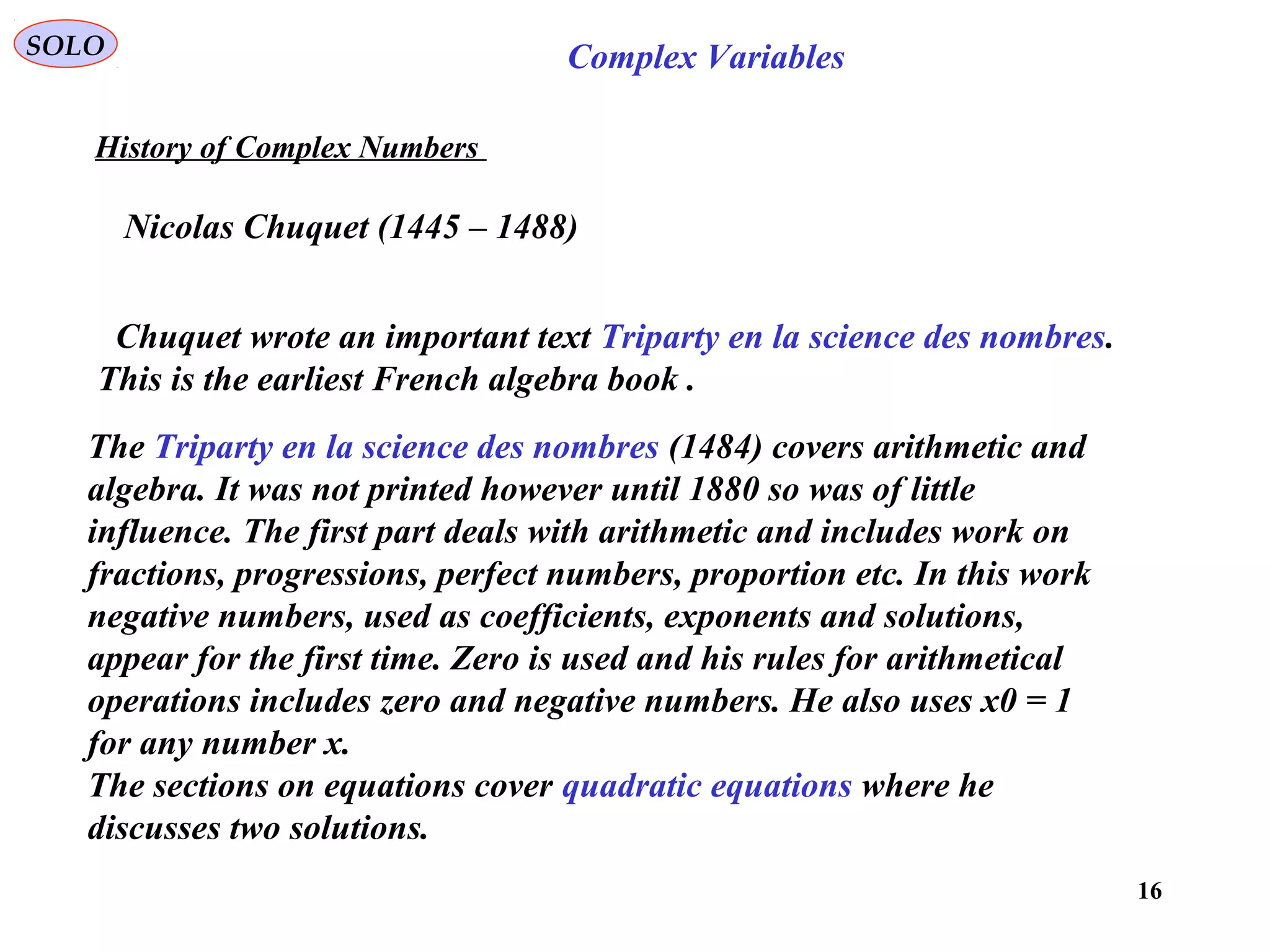

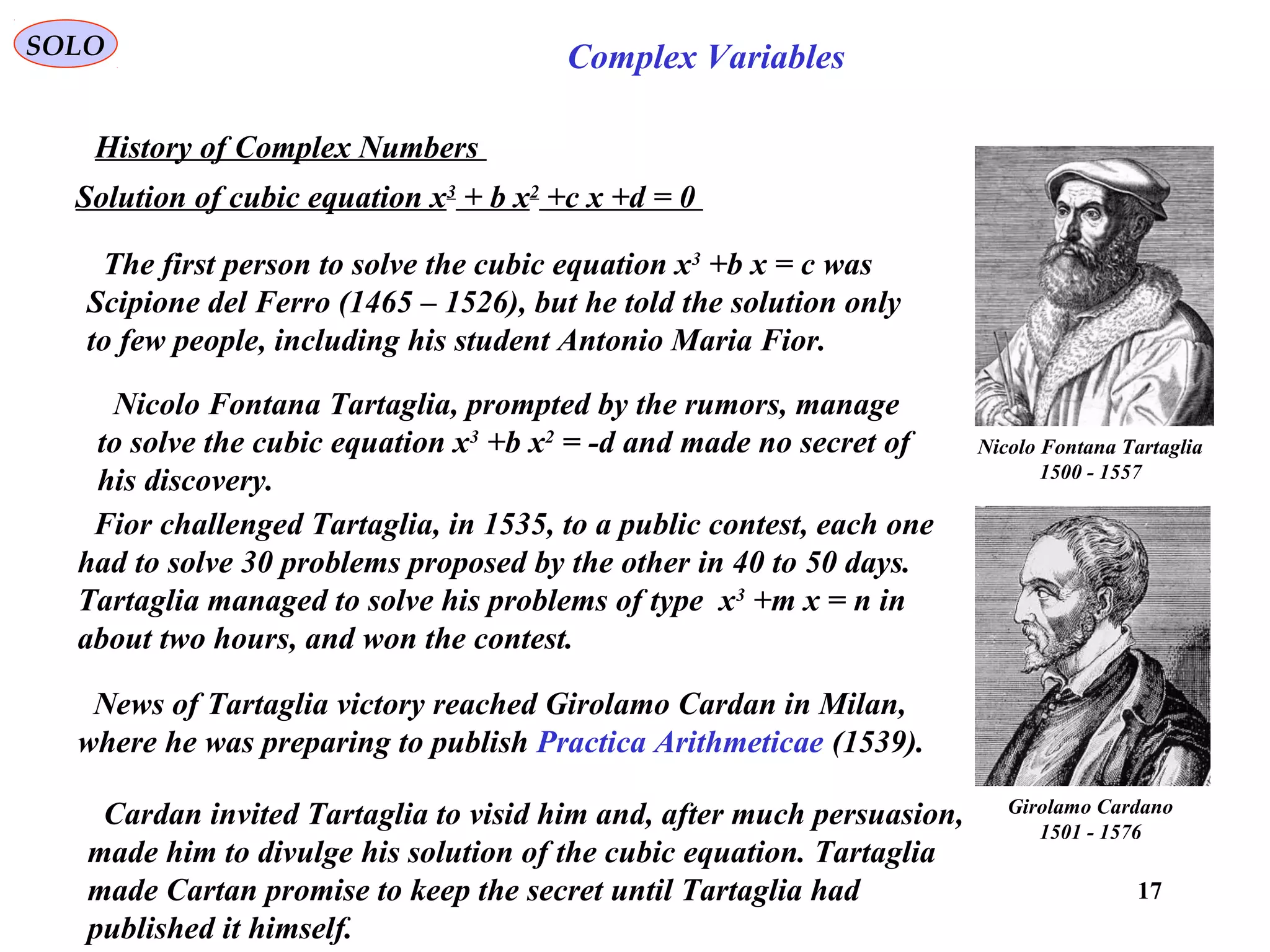

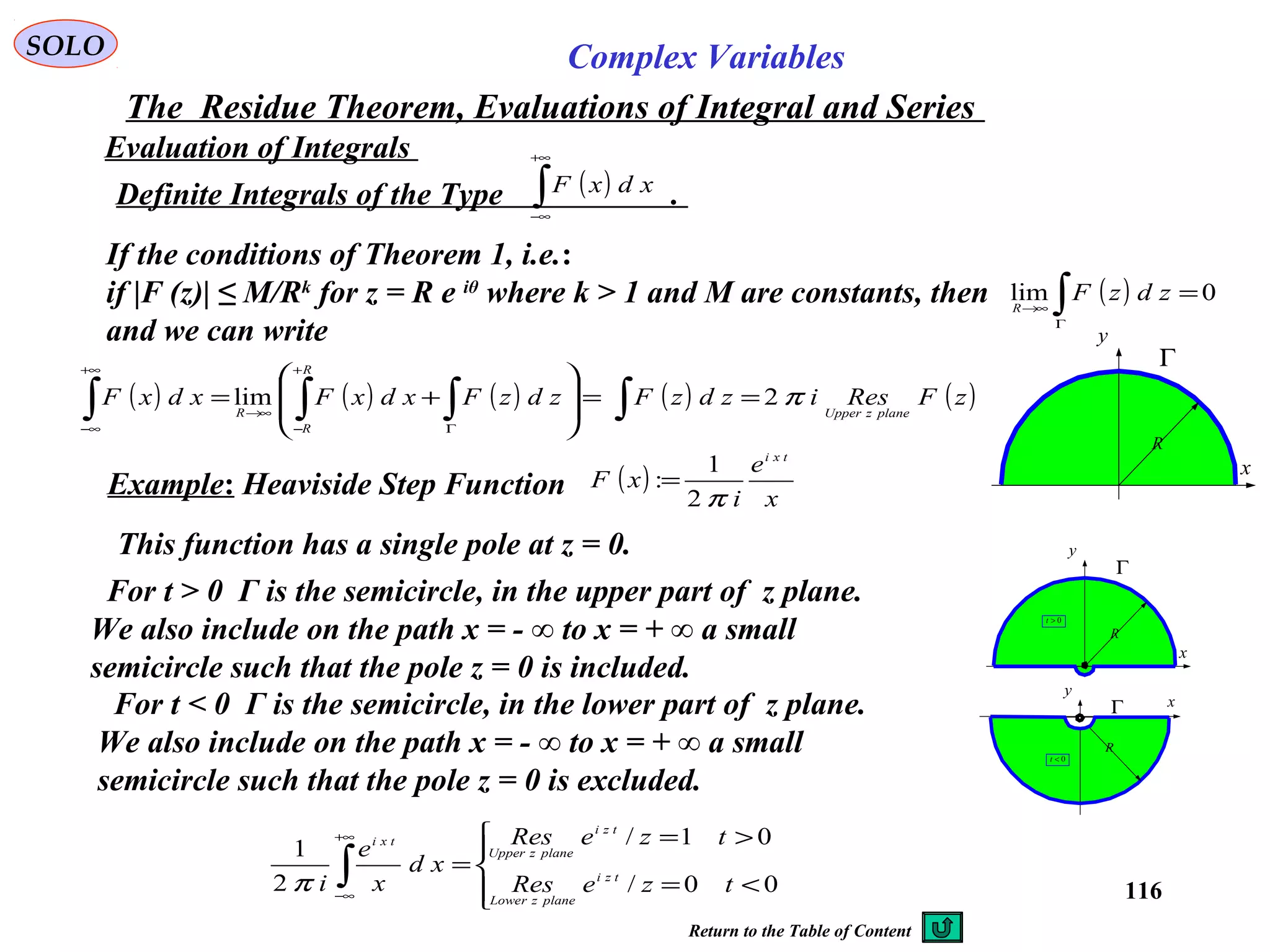

History of Complex Numbers

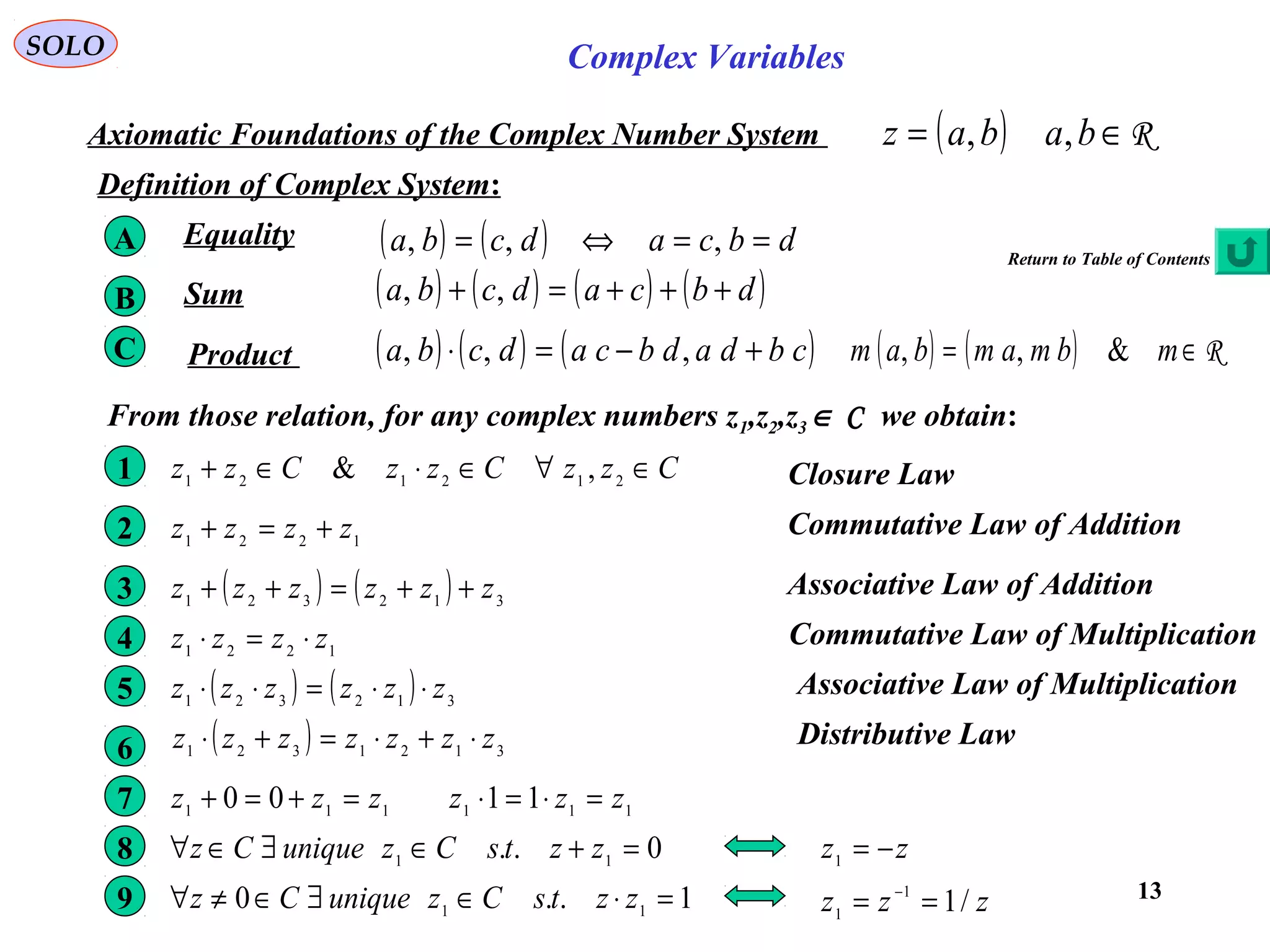

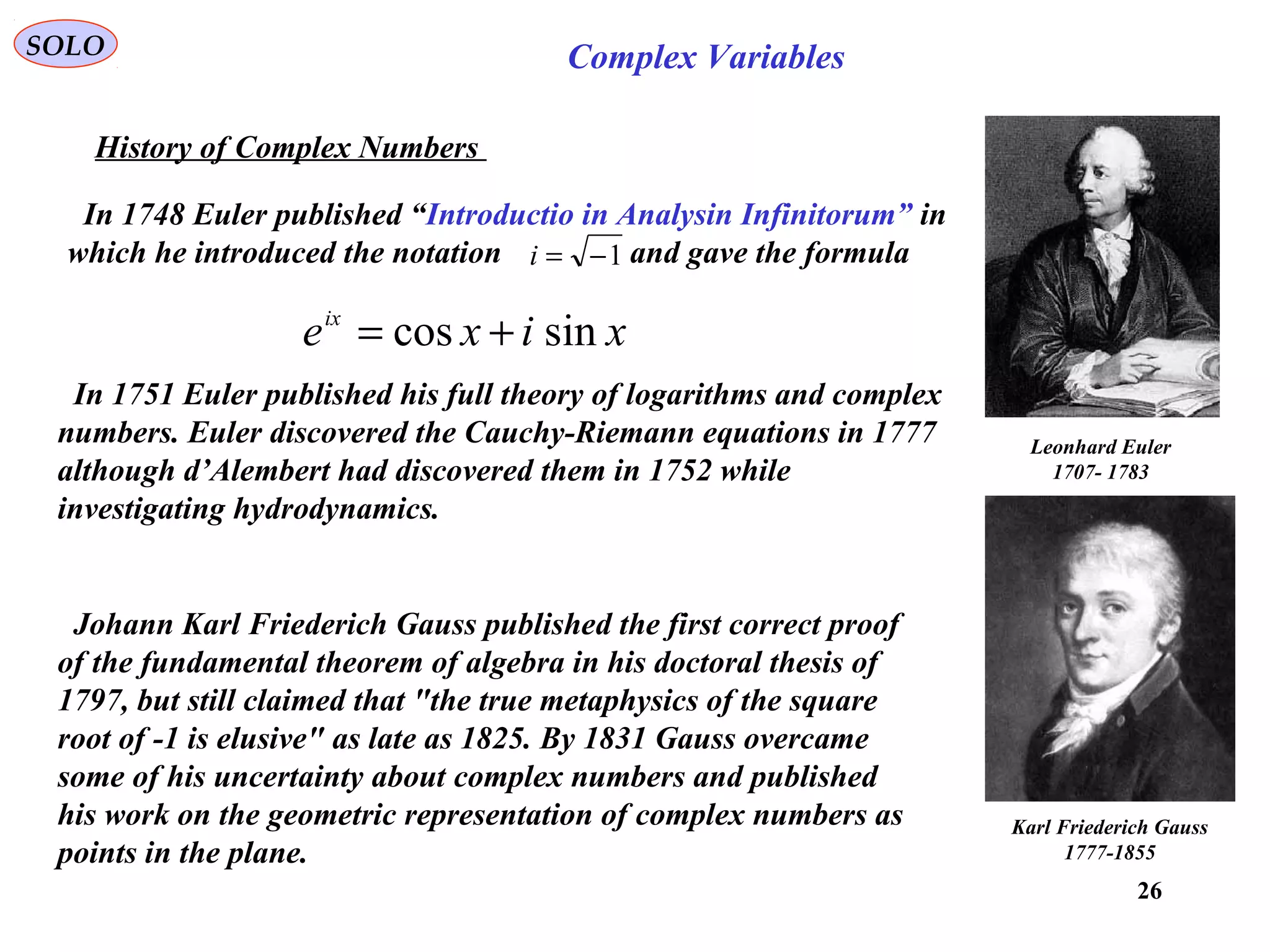

Abraham bar Hiyya Ha-Nasi הנשיא חייא בר אברהם

writes the work Hibbur ha-Meshihah ve-ha-Tishboret

והתשבורת המשיחה חבור , translated in 1145 into Latin as Liber

embadorum, which presents the first complete solution to the

quadratic equation.

Abraham bar Hiyya Ha-Nasi (הנשיא חייא בר אברהם Abraham son of

[Rabbi] Hiyya "the Prince") (1070 - 1136?) was a Spaish Jewish

Mathematician and astronomer, also known as Savasorda (from the

Arabic الشرطة صاحب Sâhib ash-Shurta "Chief of the Guard"). He

lived in Barcelona.

Abraham bar iyya ha-NasiḤ [2]

(1070 – 1136 or 1145)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-15-2048.jpg)

![30

SOLO Complex Variables

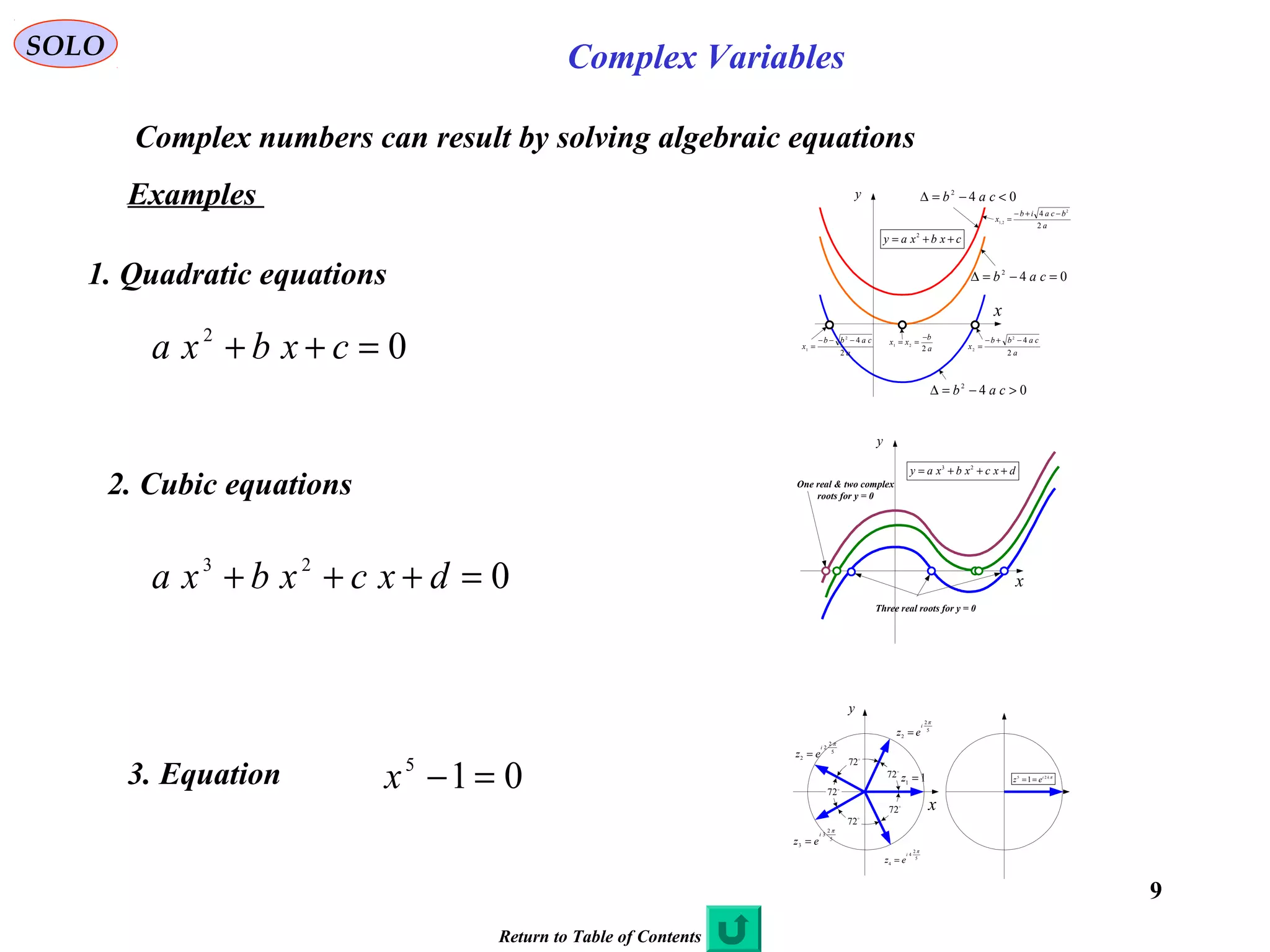

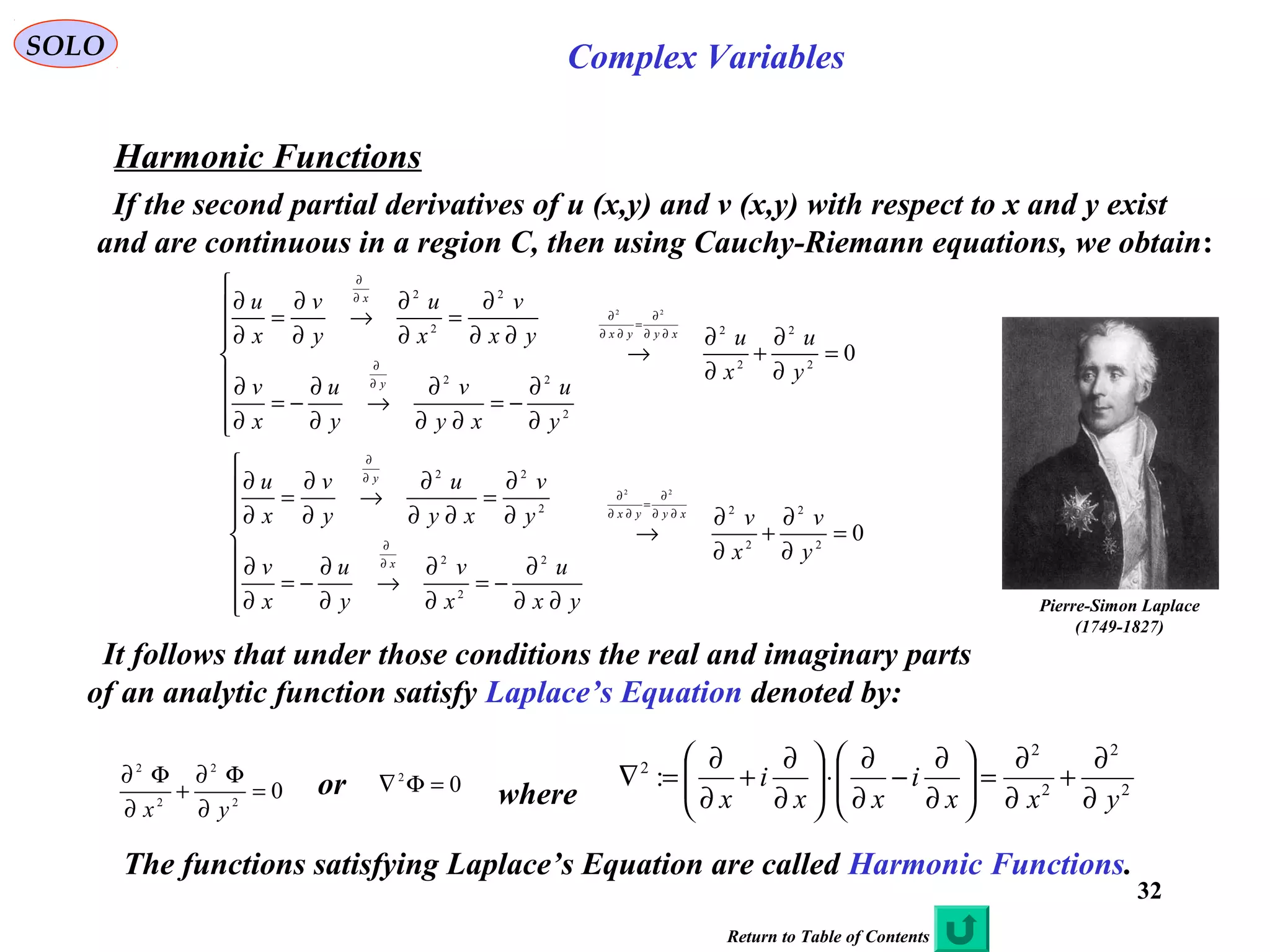

Analytic, Holomorphic, MeromorphicFunctions

Return to Table of Contents

A Meromorphic Function on an open subset D of the complex plane is a

function that is Holomorphic on all D except a set of isolated points, which are

poles for the function. (The terminology comes from the Ancient Greek meros

(μέρος), meaning “part”, as opposed to holos ( λος)ὅ , meaning “whole”.)

The word “Holomorphic" was introduced by two of Cauchy's students, Briot

(1817–1882) and Bouquet (1819–1895), and derives from the Greek λοςὅ

(holos) meaning "entire", and μορφή (morphē) meaning "form" or

"appearance".[2]

Today, the term "holomorphic function" is sometimes preferred to "analytic

function", as the latter is a more general concept. This is also because an

important result in complex analysis is that every holomorphic function is

complex analytic, a fact that does not follow directly from the definitions. The

term "analytic" is however also in wide use.

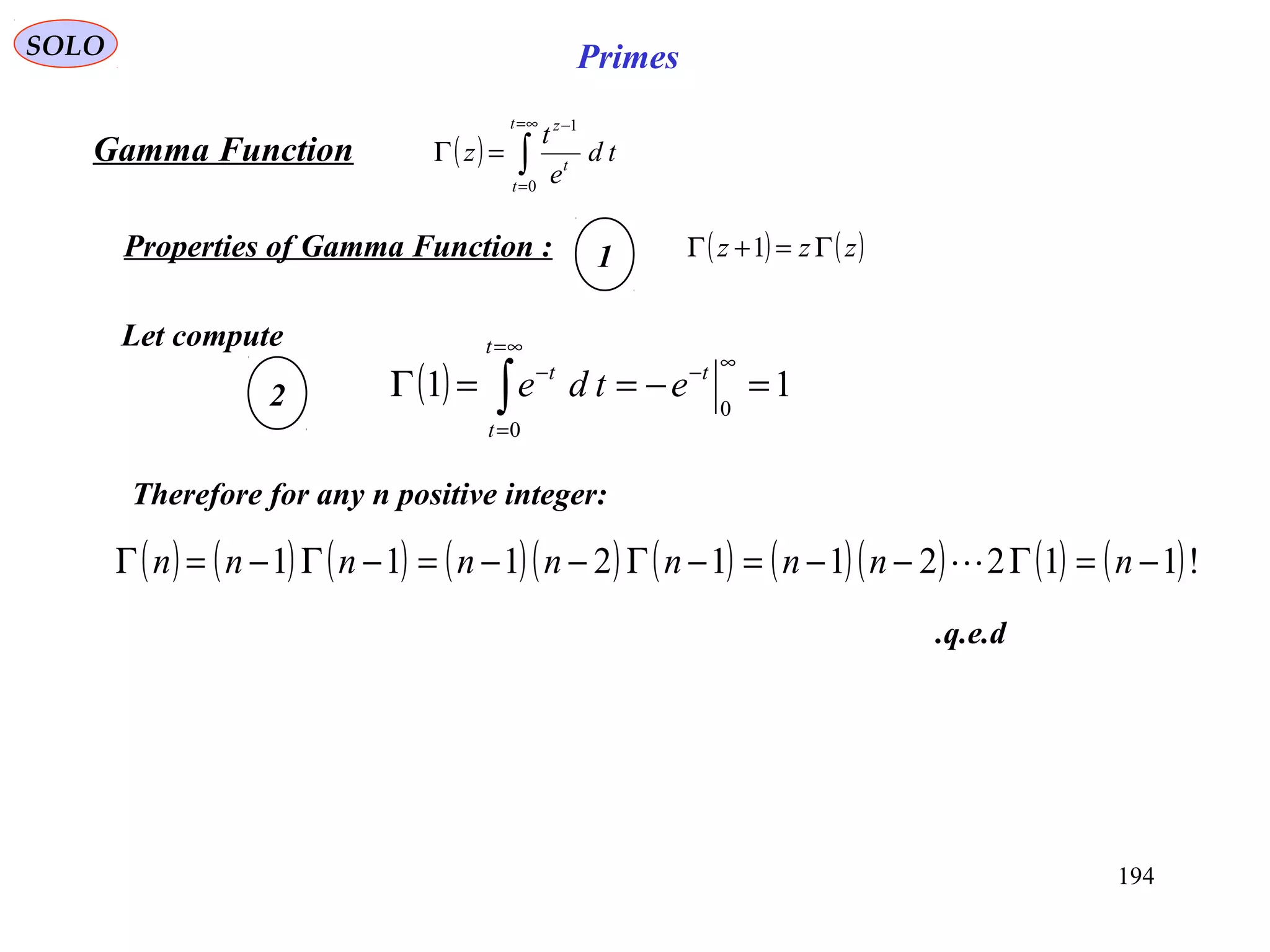

The Gamma Function is Meromorphic in the

whole complex plane

Poles](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-30-2048.jpg)

![34

SOLO Complex Variables

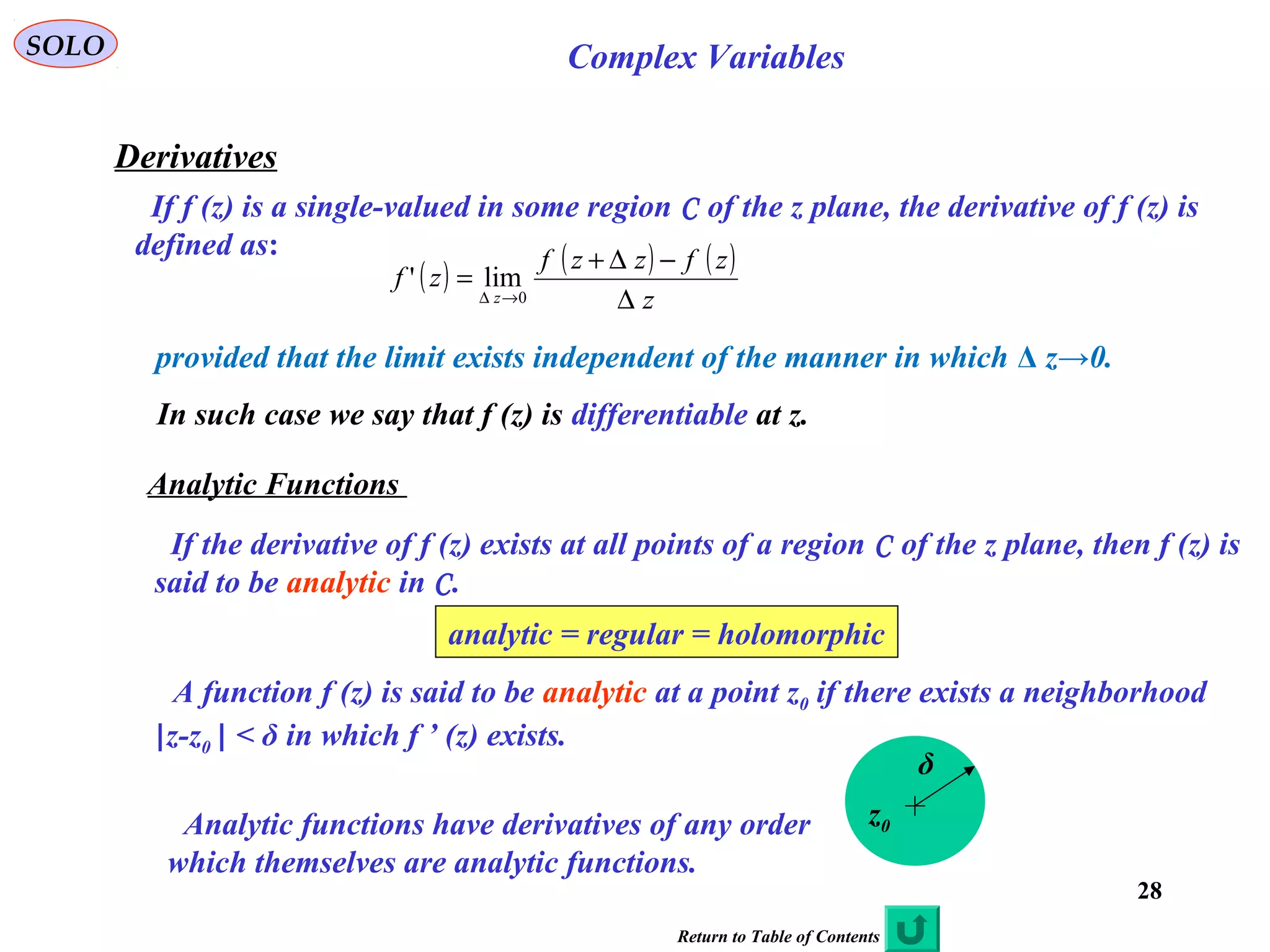

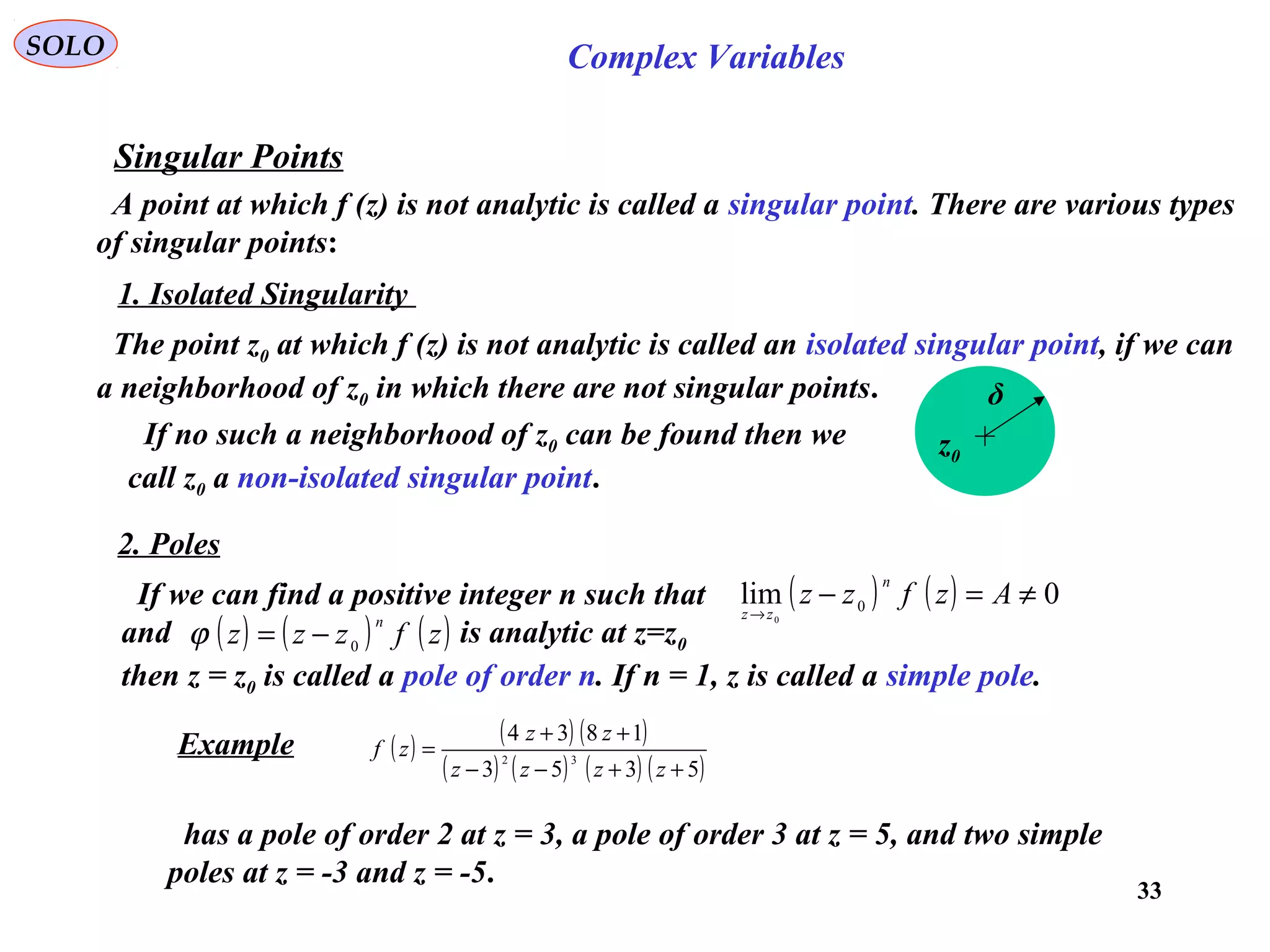

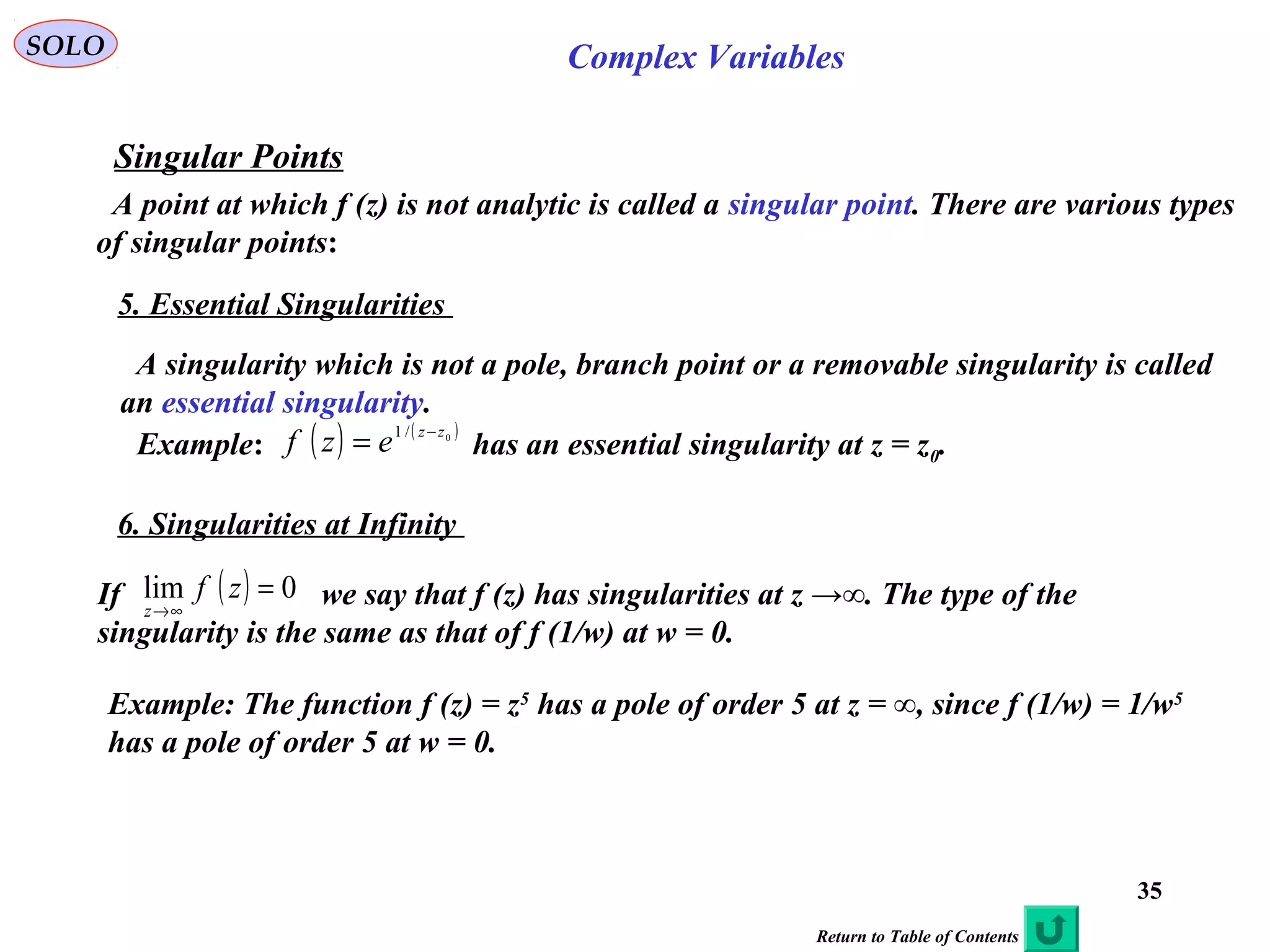

Singular Points

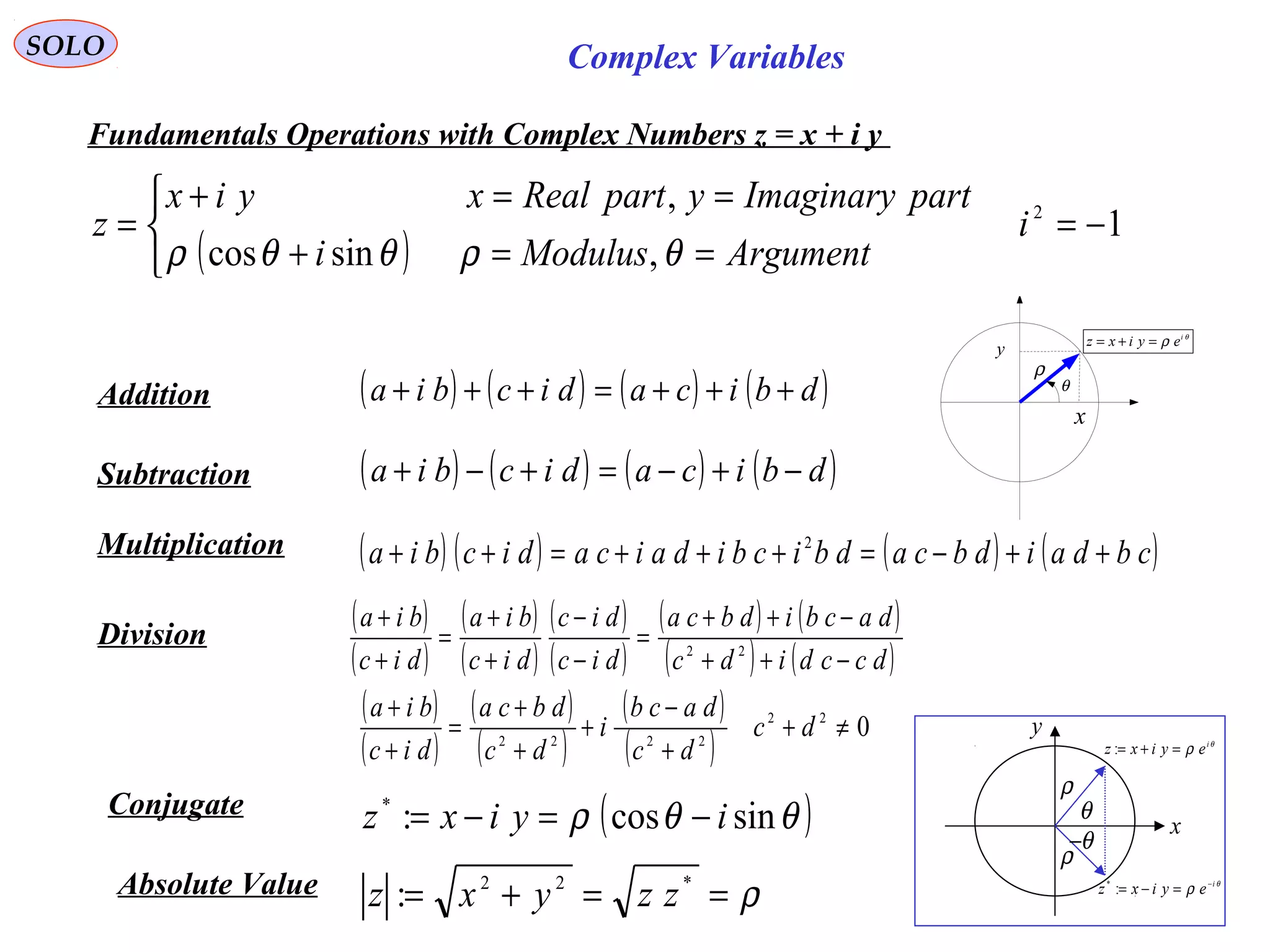

A point at which f (z) is not analytic is called a singular point. There are various types

of singular points:

3. Branch Points

If f (z) is a multiple valued function at z0, then this is a branch point.

Examples:

( ) ( ) n

zzzf

/1

0−= has a branch point at z=z0

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]0201ln zzzzzf −−= has a branch points at z=z01 and z=z02

4. Removable Singularities

The singular point z0 is a removable singularity of f (z) if exists.( )zf

zz 0

lim

→

Examples: The singular point z = 0 of is a removable singularity

z

zsin

1

sin

lim0

=→

z

z

z](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-34-2048.jpg)

![37

SOLO Complex Variables

Complex Line Integrals

Let f (z) be continuous at all points on a curve C of a finite length L.

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑ ==

− ∆=−=

n

i

ii

n

i

iiin zfzzfS

11

1 ξξ

C

1

z

nzb =

2z

0

za =

1−iz

iz

1

ξ

2

ξ

i

ξ

n

ξ

Let subdivide C into n parts by n arbitrary points

z1, z2,…,zn, and call a=z0 and b=zn. On each arc joining

zi-1 to zi choose a point ξi. Define the sum:

Let the number of subdivisions n increase in such a

way that the largest of Δzi approaches zero, then the sum approaches a limit

that is called the line integral (also Riemann-Stieltjes integral).

( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∑ ==∆=

=

→∆∞→

C

b

a

n

i

ii

z

nn

zdzfzdzfzfS

i

1

0

limlim ξ

Properties of Integrals

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )∫∫∫ +=+

CCC

zdzgzdzfzdzgzf ( ) ( ) constantAzdzfAzdzfA

CC

== ∫∫

( ) ( )∫∫ −=

a

b

b

a

zdzfzdzf ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫ +=

b

c

c

a

b

a

zdzfzdzfzdzf

( ) ( ) ( ) CoflengthLandConMzfLMzdzfzdzf

CC

≤≤≤ ∫∫

Return to Table of Contents](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-37-2048.jpg)

![40

SOLO Complex Variables

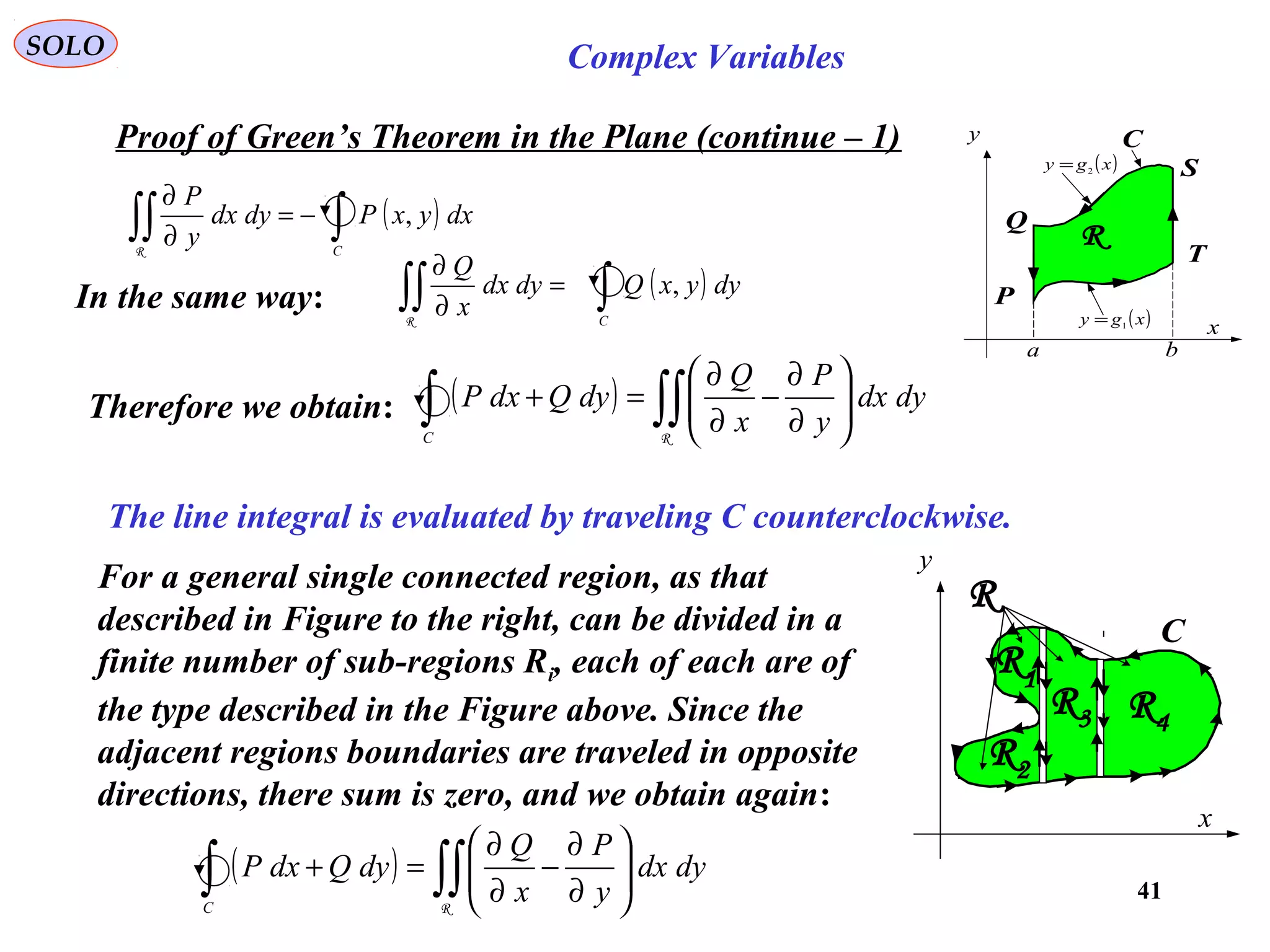

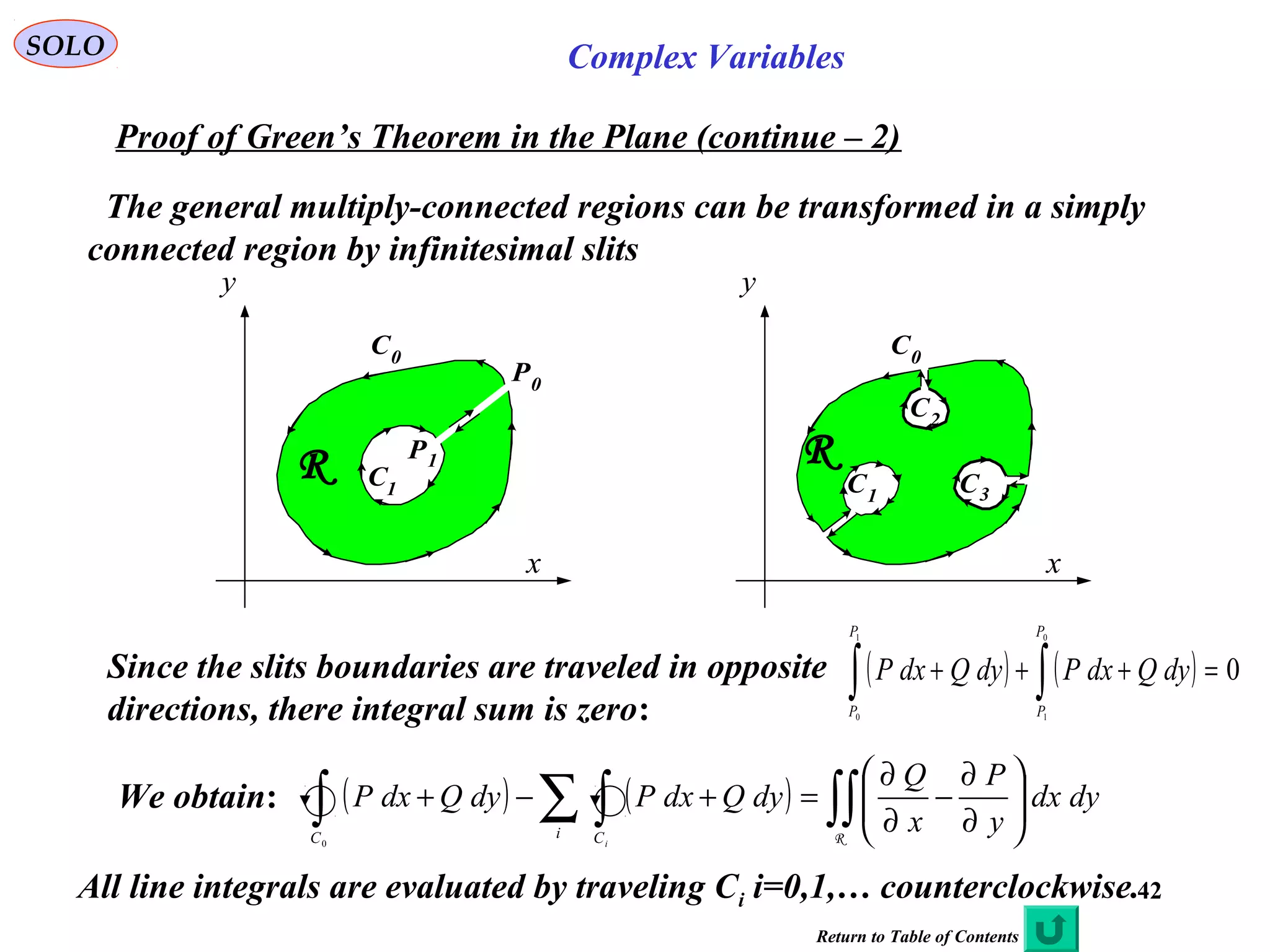

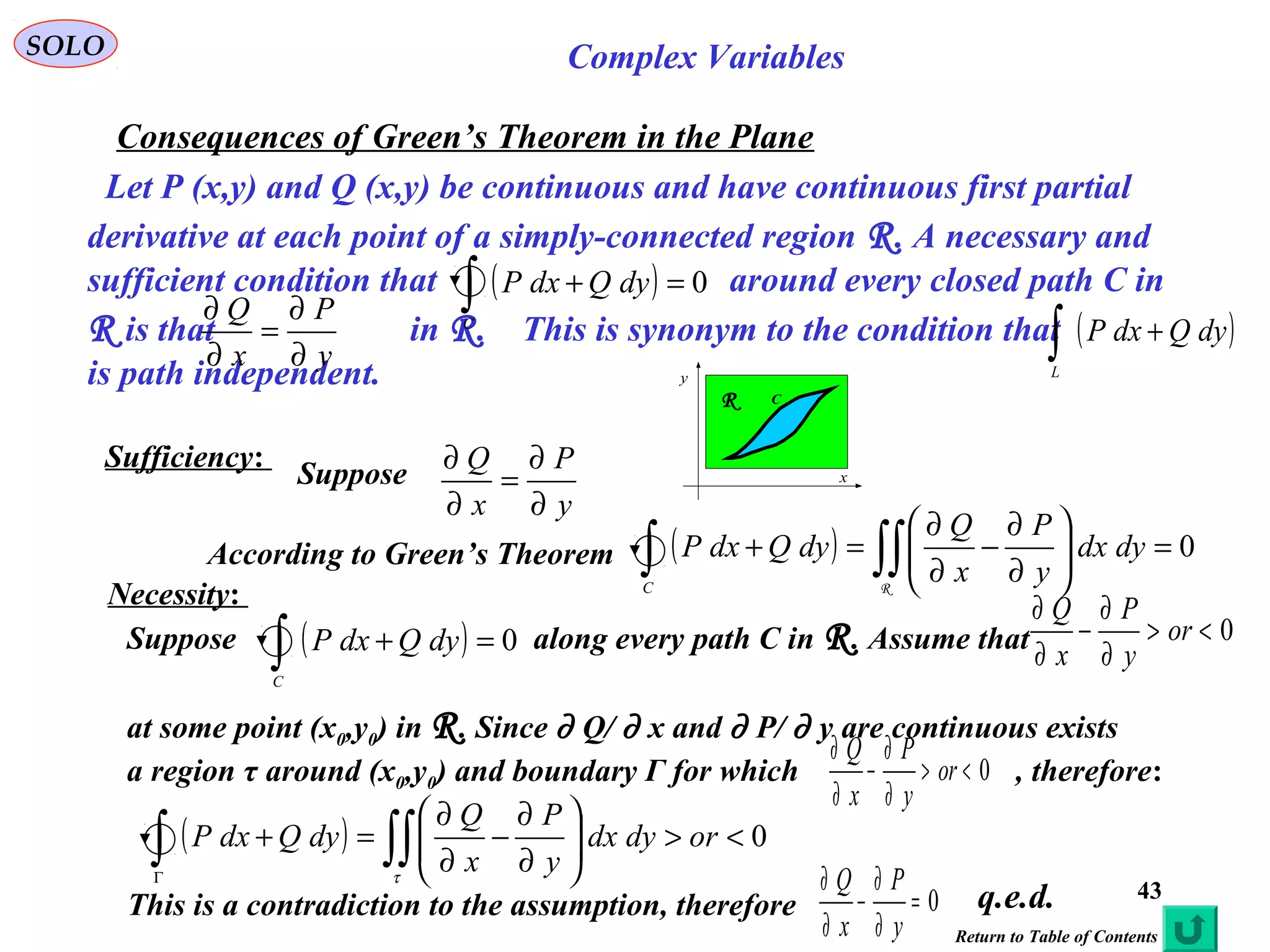

Proof of Green’s Theorem in the Plane C

R

P

T

S

Q

a b

x

y

( )xgy 2=

( )xgy 1=

Start with a region R and the boundary curve C, defined

by S,Q,P,T, where QP and TS are parallel with y axis.

( )

( )

∫ ∫∫∫

=

=

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

b

a

xgy

Xgy

dy

y

P

dxdydx

y

P

2

R

By the fundamental lemma

of integral calculus:

( )

( )

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ]xgxPxgxPyxPdy

y

yxP xgy

xgy

xgy

Xgy

12

,,,

, 2

1

2

−==

∂

∂ =

=

=

=

∫

Therefore: ( )[ ] ( )[ ]∫∫∫∫ −=

∂

∂

b

a

b

a

dxxgxPdxxgxPdydx

y

P

12

,,

R

but: ( )[ ] ( )[ ]∫∫ =

a

bSQ

dxxgxPdxxgxP 22

,, integral along curve SQ

( )[ ] ( )[ ]∫∫ =

b

aPT

dxxgxPdxxgxP 11

,, integral along curve PT

If we add to those integrals: ( ) ( ) 00,, === ∫∫ dxsincedxyxPdxyxP

QPTS

we

obtain:

( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )∫∫∫∫∫∫∫ −=−−−−=

∂

∂

CTSPTQPSQ

dxyxPdxyxPdxxgxPdxyxPdxxgxPdydx

y

P

,,,,, 12

R

Assume that PT is defined by the function y = g1 (x) and

SQ is defined by the function y = g2 (x), both smooth and

y

P

∂

∂

is continuous in R:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-40-2048.jpg)

![47

SOLO Complex Variables

Proof of Cauchy-Goursat Theorem (continue – 2)

C

F

DE

A

B

I

∆

IV

∆

II

∆ III

∆

( ) ( )∫∫ ∆∆

≤

n

dzzfdzzf n

4

For an analytic function f (z) compute ( )

( ) ( )

( )0

0

0

0

':, zf

zz

zfzf

zz −

−

−

=η

( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) 0'''lim,lim 000

0

0

0

00

=−=

−

−

−

= →→

zfzfzf

zz

zfzf

zz zzzz

η

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )0000000

,'&,..,0 zzzzzzzfzfzfzzwheneverzzts −+−+=<−<∃>∀ ηδεηδε

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫∫ ∆∆

←

∆∆

−≤−+−+≤

nnnn

dzzzzzdzzzzzdzzzzfzfdzzf

TheoremIntegralCauchy

0000

0

)00 ,,' ηη

n∆

0z

na

nb

nc

z 0

zz −

0

zzcbaP nnnn

−≥++=

( ) ( ) ( )

2

2

00

2

,

==≤−≤ ∫∫∫ ∆∆∆

nnn

P

PdzPdzzzzzdzzf

nnn

εεεη

But , where Pn the perimeter

of Δn and P the perimeter of Δ are related, by construction, by

( ) δεη <≤−< n

Pzzzz 00

&,

n

n PP 2/=

q.e.d.

( ) ( ) ( ) 0

4

44

0

2

2

=→=≤≤ ∫∫∫ ∆

→

∆∆

dzzfP

P

dzzfdzzf n

nn

n

ε

εε](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-47-2048.jpg)

![48

SOLO Complex Variables

Proof of Cauchy-Goursat Theorem (continue – 3)

n

z1

z

2

z

1−i

z

i

z

1−n

z

n

∆1∆

2∆

3

∆

i

∆

C

O

q.e.d.

For the general case of a simple closed curve C

we take n points on C: z1, z2,…,zn and a point

O inside C. We obtain n triangles Δ1, Δ2,.., Δn,

for each of them we proved Cauchy-Goursat Theorem.

Let define the sum: ( ) ∑= − −

∆=

n

i zz

iin

ii

zzfS

1

1

:

we have: ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 0

1

1

=++= ∫∫∫∫

−

−∆

i

i

i

ii

z

O

O

z

z

z

dzzfdzzfdzzfdzzf

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] ( )

n

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

ii

S

n

i

z

z

i

n

i

z

z

i

n

i

z

z

ii

n

i

z

z

n

i

dzzfdzzfzfdzzfzfzfdzzfdzzf ∑ ∫∑∫∑ ∫∑ ∫∑ ∫ ===== ∆ −−−−

+−=+−===

11111

1111

0

( ) ( ) ( )ε

ε

NnforSdzzfdzzfS n

CC

nn

><−→= ∫∫∞→

2

lim

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] ( )

221

1

111

11

εε

=−≤−≤−≤→−= ∑∑∑ ∫∑∫ =

−

===

−−

n

i

ii

n

i

i

n

i

z

z

in

n

i

z

z

in

zz

L

dzfzfdzzfzfSdzzfzfS

i

i

i

i

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 0

22

=→>=+<+−≤ ∫∫∫ C

nn

CC

dzzfNnforSSdzzfdzzf εε

εε

Since we proved that , we can write:( ) 0=∫∆

dzzf

Return to Table of Contents](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-48-2048.jpg)

![50

SOLO Complex Variables

Cauchy’s Integral Formulas

Augustin Louis Cauchy

)1789-1857(

If f (z) is analytic inside and on a simple closed curve C

and a is any point inside C then

( ) ( )

∫ −

=

C

dz

az

zf

i

af

π2

1

C

x

y

R

a

Γ

Proof:

Let chose a circle Γ with center at a

[ ]{ }πθε θ

2,0,: ∈+==Γ i

eazz

Since f (z)/ (z-a) is analytic in the region defined

between C and the circle Γ we can use:

( ) ( )

∫∫ Γ

−

=

−

zd

az

zf

zd

az

zf

C

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )afidafidei

e

eaf

zd

az

zf i

i

i

πθθε

ε

ε

ππ

θ

θ

θ

ε

21lim

2

0

2

0

0

===

+

=

− ∫∫∫ →

Γ

therefore:

( ) ( )

∫ −

=

C

dz

az

zf

i

af

π2

1

q.e.d.

Cauchy’s Integral Formulas and Related Theorems

Return to Table of Contents](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-50-2048.jpg)

![52

SOLO Complex Variables

Morera’s Theorem (the converse of Cauchy’s theorem)

If f (z) is continuous in a simply-connected region R and if

around every simple closed curve C in R then

f (z) ia analytic in R.

( ) 0=∫C

dzzf

B

x

y

R

A

C1

C2

D1

D2

a

z

Proof:

Since around every closed curve C in R( ) 0=∫C

dzzf

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫∫∫∫∫ =→−=+==

BDAcBDAcBDAcBDAcACBDBDAcACBDDAC

dzzfdzzfdzzfdzzfdzzfdzzfdzzf

2211221122111122

0

The integral is independent on path

between two points, if the path is in R

( ) ( )∫=

z

a

dzzfzF

Let choose a straight path between z and z+Δz

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]∫∫∫

∆+∆+

−

∆

=−

−

∆

=−

∆

−∆+

zz

z

z

a

zz

a

udzfuf

z

zfudufuduf

z

zf

z

zFzzF 11

Since f (z) is continuous ( ) ( ) δε <−≤− zuwheneverzfuf

Therefore

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )zf

zd

zFd

zudzfuf

z

zf

z

zFzzF

zz

z

=→<∆∀=−

∆

≤−

∆

−∆+

∫

∆+

δε

1

C

x

y

R z

Νδz+∆ z

Since F (z) has a derivative in R, it is analytic, and so are its derivatives, i.e. f (z)

Return to Table of Contents

Giacinto Morera

1856 - 1907](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-52-2048.jpg)

![62

SOLO Complex Variables

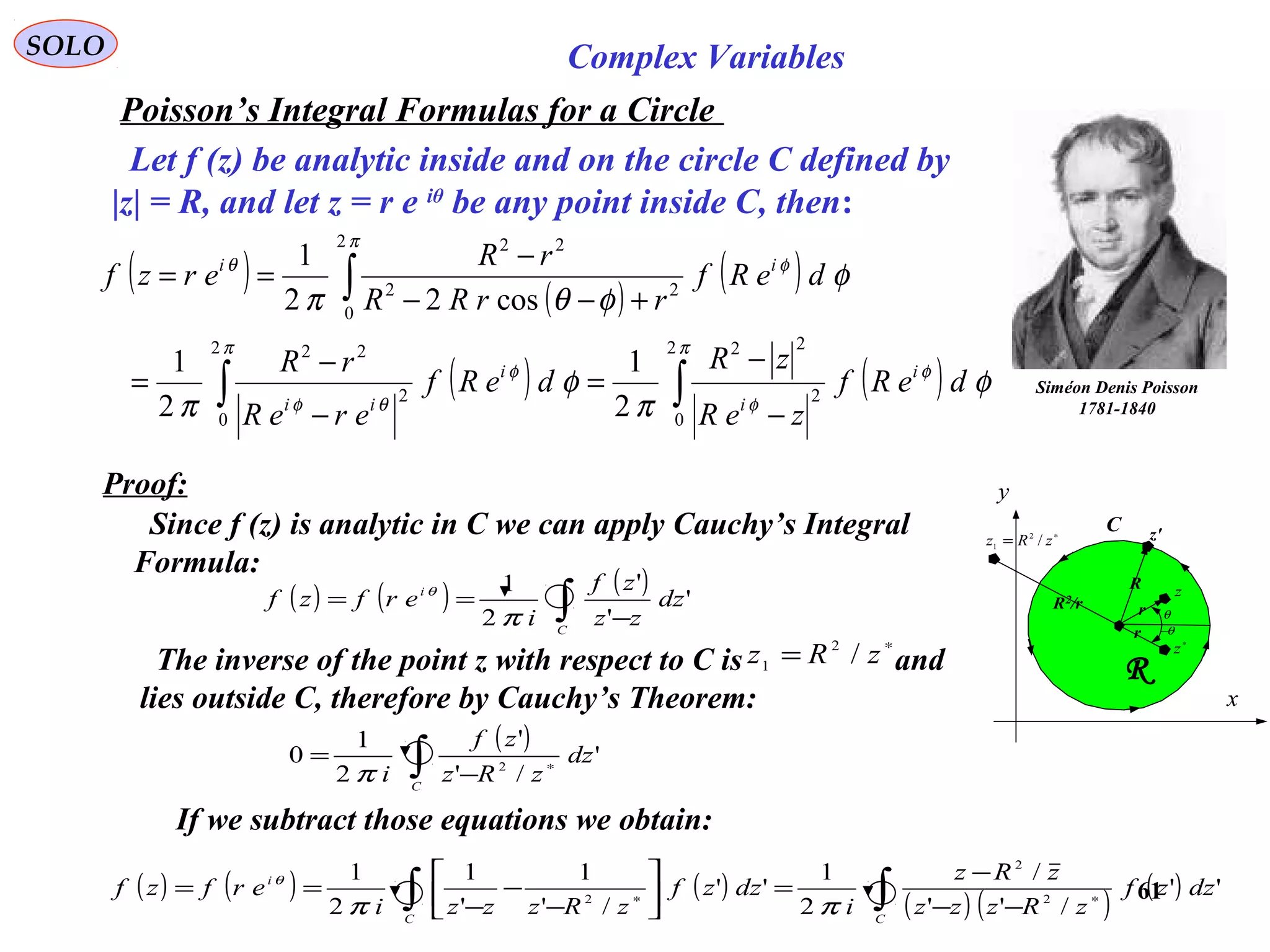

Poisson’s Integral Formulas for a Circle

Siméon Denis Poisson

1781-1840

Proof (continue):

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )[ ] ( )

( ) ( )

( )( ) ( )

( )

( )( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )∫

∫

∫

∫

∫

+−−

−

=

−−

−

=

−−

−

=

−−

−

=

−−

−

==

−−

+

∗

π

φ

π

φ

θφθφ

π

φ

θφθφ

φθ

π

φφ

θφθφ

θθ

θ

φ

φθπ

φ

π

φ

π

φ

π

π

2

0

22

22

2

0

22

2

0

22

2

0

2

2

2

2

cos22

1

2

1

2

1

/

/

2

1

''

/''

/

2

1

deRf

RrRr

rR

deRf

ereRereR

rR

deRf

eRerereR

eRr

deRieRf

erReRereR

erRer

i

dzzf

zRzzz

zRz

i

erfzf

i

i

iiii

i

iiii

i

ii

iiii

ii

C

i

Writing we have:( ) ( ) ( )θθθ

,, rviruerf i

+=

( ) ( )

( )

( )∫ +−−

−

=

π

φφ

φθπ

θ

2

0

22

22

,

cos22

1

, dRu

RrRr

rR

ru

( ) ( )

( )

( )∫ +−−

−

=

π

φφ

φθπ

θ

2

0

22

22

,

cos22

1

, dRv

RrRr

rR

rv

q.e.d.

C

x

y

R

R

z'

rR2/r

θ

∗

z

z

r θ−

∗

= zRz /2

1

Return to Table of Contents](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-62-2048.jpg)

![81

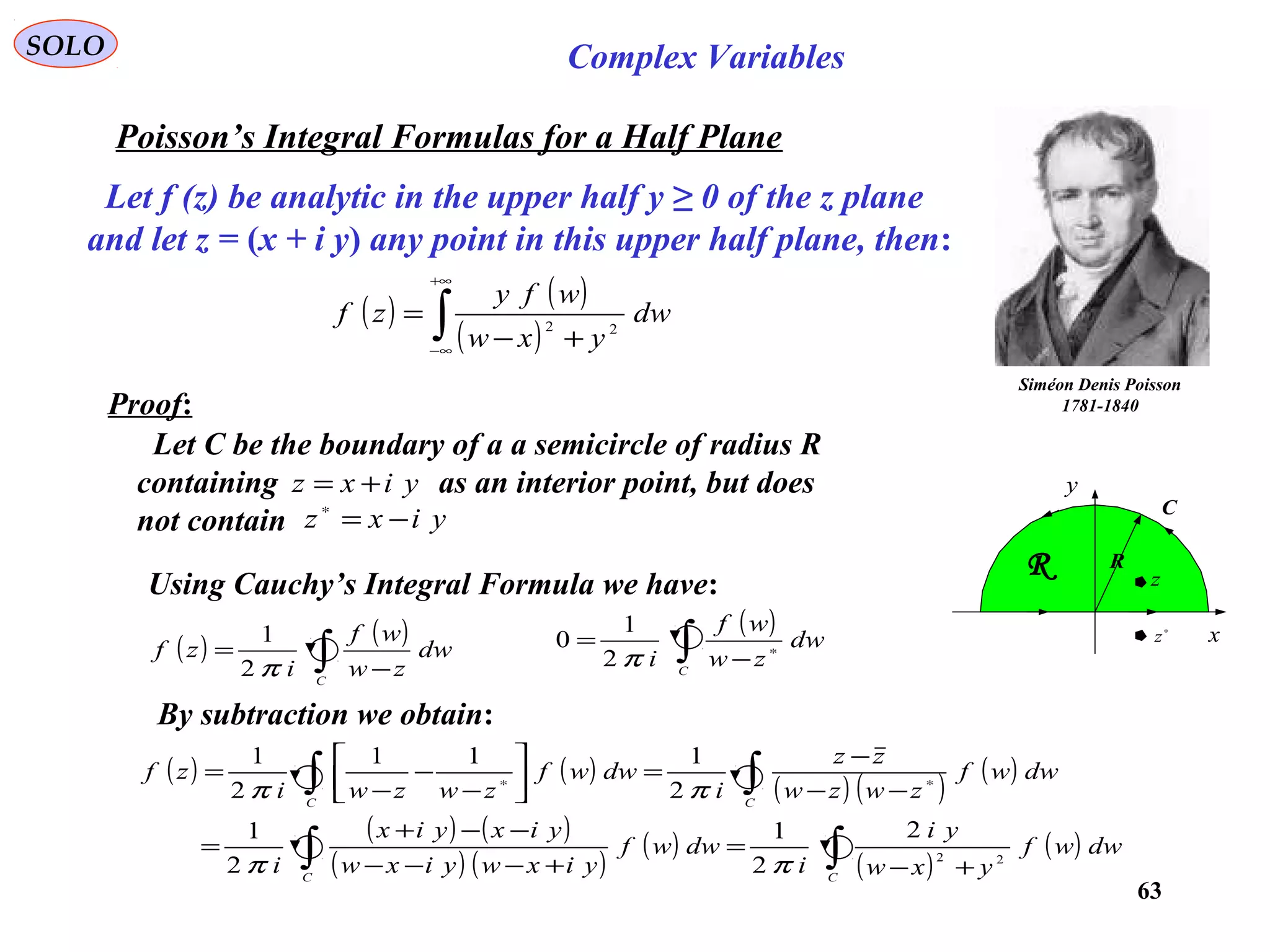

SOLO Complex Variables

Weierstrass M (Majorant) Test

Karl Theodor Wilhelm

Weierstrass

(1815 – 11897)

The most commonly encountered test for Uniform

Convergence is the Weierstrass M Test.

Proof:

Since converges, some number N exists such that for n + 1 ≥ N,

If we can construct a series of numbers , in

which Mi ≥ |ui(x)| for all x in the interval [a,b] and

is convergent, the series ui(x) will be uniformly

convergent in [a,b].

∑

∞

1 iM

∑

∞

1 iM

∑

∞

1 iM

ε<∑

∞

+= 1ni

iM

This follows from our definition of convergence. Then, with |ui(x)| ≤ Mi for

all x in the interval a ≤ x ≤ b, ( ) ε<∑

∞

+= 1ni

i xu

Hence ( ) ( ) ( ) ε<=− ∑

∞

+= 1ni

in xuxsxS

and by definition is uniformly convergent in [a,b]. Since we

specified absolute values in the statement of the Weierstrass M Test, the

series is also Absolutely Convergent. Return to the Table of Content

∑

∞

=1i iu

∑

∞

=1i iu](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-81-2048.jpg)

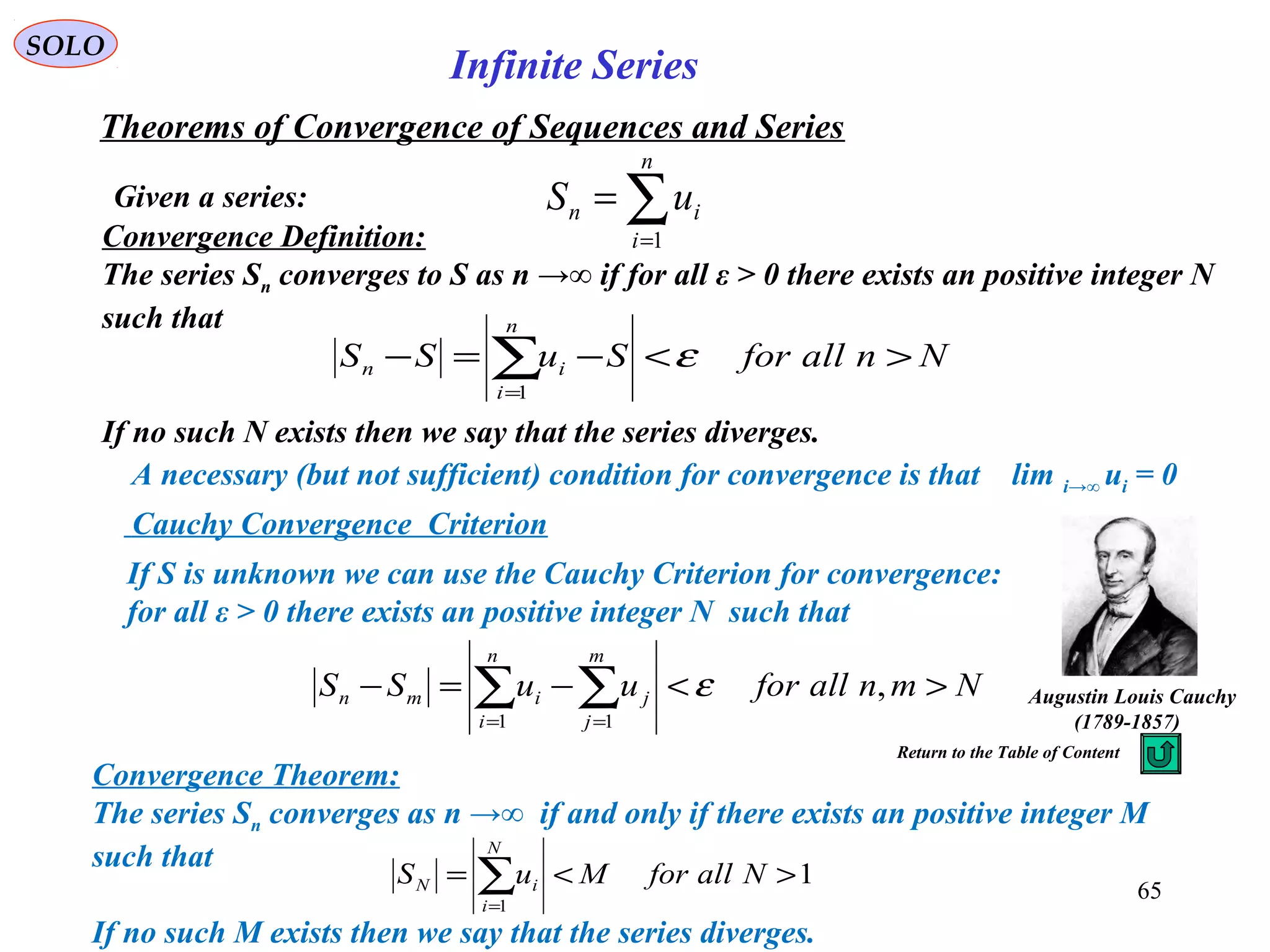

![SOLO Complex Variables

Abel’s Test

Niels Henrik Abel

( 1802 – 1829)

If

and the functions fn(x) are monotonic decreasing |

fn+1(x) ≤ fn(x)| and bounded, 0 ≤ fn(x) ≤ M, for all x in

[a,b], then Converges Uniformly in [a,b].

( ) ( )

convergentAa

xfaxu

n

nnn

,=

=

∑

( )∑n n xu

( ) ( ) [ ] ( ) [ ]bainconvergentuniformlyisxu

xd

d

baincontinuousarexu

xd

d

andxu n nnn ,&, 1∑

∞

=

Return to the Table of Content

Uniformly convergent series have three particular useful properties:

1.If the individual terms un(x) are continuous, the series sum

is also continuous.

2. If the individual terms un(x) are continuous, the series may be integrated term by term.

The sum of the integrals is equal to to the integral of the sum, then

3.The derivative of the series sum f (x) equals the sum of the individual term derivatives

providing the following conditions are satisfied

( ) ( )∑

∞

=

= 1n n xuxf

( ) ( )∑ ∫∫

∞

=

= 1n

b

a

n

b

a

xdxuxdxf

( ) ( )∑

∞

=

= 1n n xu

xd

d

xf

xd

d](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-82-2048.jpg)

![109

SOLO Complex Variables

The Residue Theorem, Evaluations of Integral and Series

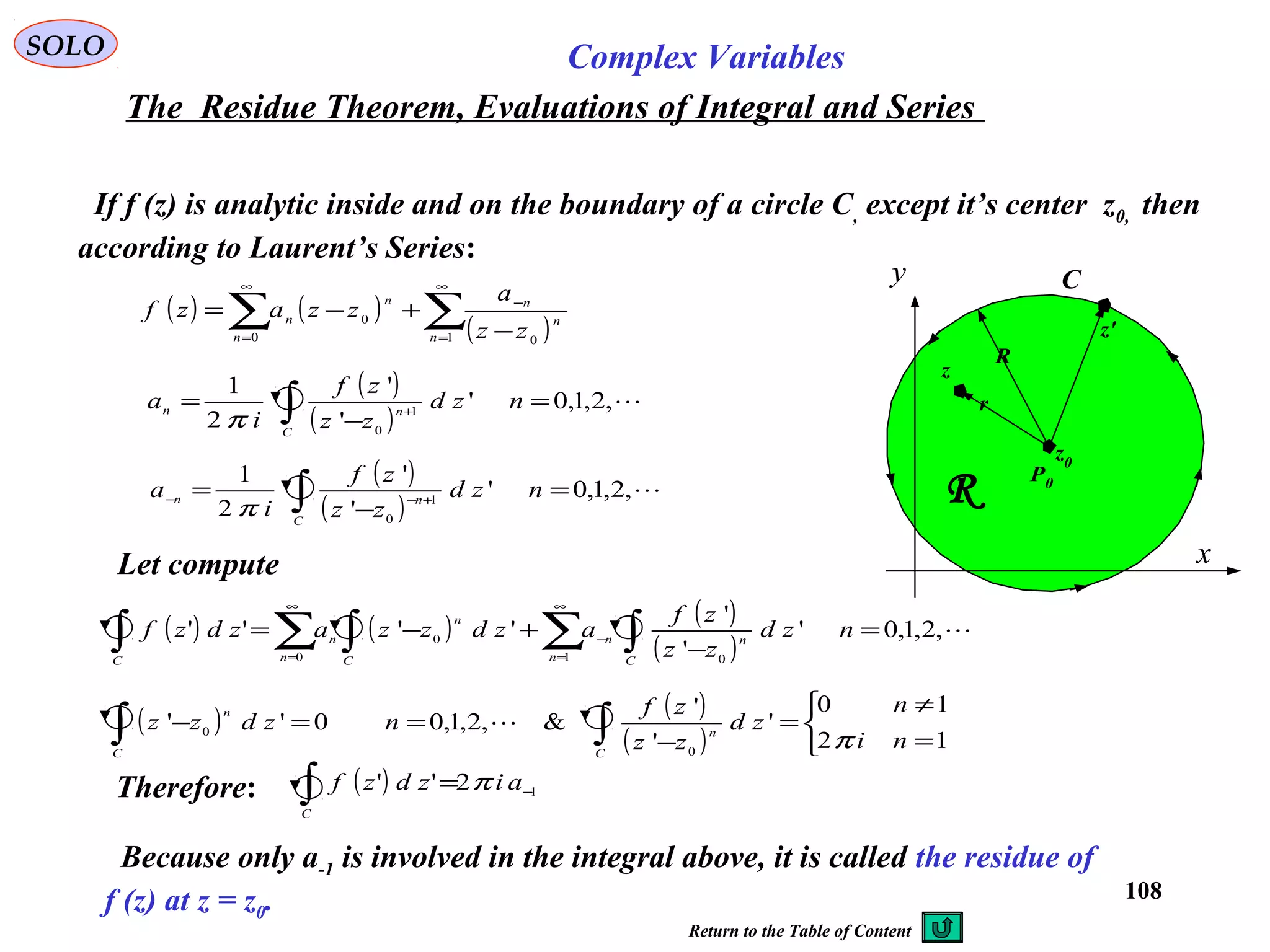

According to residue definition the residue of f (z) at z = z0 can be computed as follows:

C

x

y

R

R

z0

z

z'

r

P0

If z = z0 is a pole of order k, i.e. the Laurent series at

z0 is

Then:

( )∫=−

C

zdzf

i

a ''

2

1

1

π

Calculation of the Residues

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) +−+−++

−

++

−

+

−

= −−− 2

02010

0

2

0

2

0

1

zzazzaa

zz

a

zz

a

zz

a

k

k

( )

( ) ( )[ ]zfzz

zd

d

k

a

k

k

k

zz 01

1

1

!1

1

lim

0

−

−

= −

−

→−

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) +−+−+−+++−+−=−

++

−

−

−

−

−

2

02

1

0100

2

02

1

010

kkk

k

kkk

zzazzazzaazzazzazfzz

and:

If z = z0 is a pole of order k=1, then:

( ) ( )[ ]zfzza

zz 01

0

lim −=

→−

( ) ( )

( )∑∑ =

−

∞

= −

+−=

k

n

n

n

n

n

n

zz

a

zzazf

1 00

0

Return to the Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-109-2048.jpg)

![119

SOLO Complex Variables

The Residue Theorem, Evaluations of Integral and Series

Evaluation of Integrals

Cauchy’s Principal Value (continue – 2)

Theorem 2:

If F (z) is analytic on and inside a positive-sensed circle C of radius ε, except at the

center of C, z = z0, that is a simple pole of F (z), then

C

x

y ψC

0

z

0

θ

0

θψ +

ψ

ε

O

( ) ( )[ ]0

0

lim zFResizdzF

C

ψ

ψ

ε

=∫→

where Cψ is every arc on C of angle ψ.

Proof:

Since f (z) is analytic inside and on C by using Theorem 1 we obtain the

desired result.

The function:

( )

( ) ( )

( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]

=−=

≠−

=

→

000

00

0

lim zzzFzzzFRes

zzzFzz

zf

zz](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-119-2048.jpg)

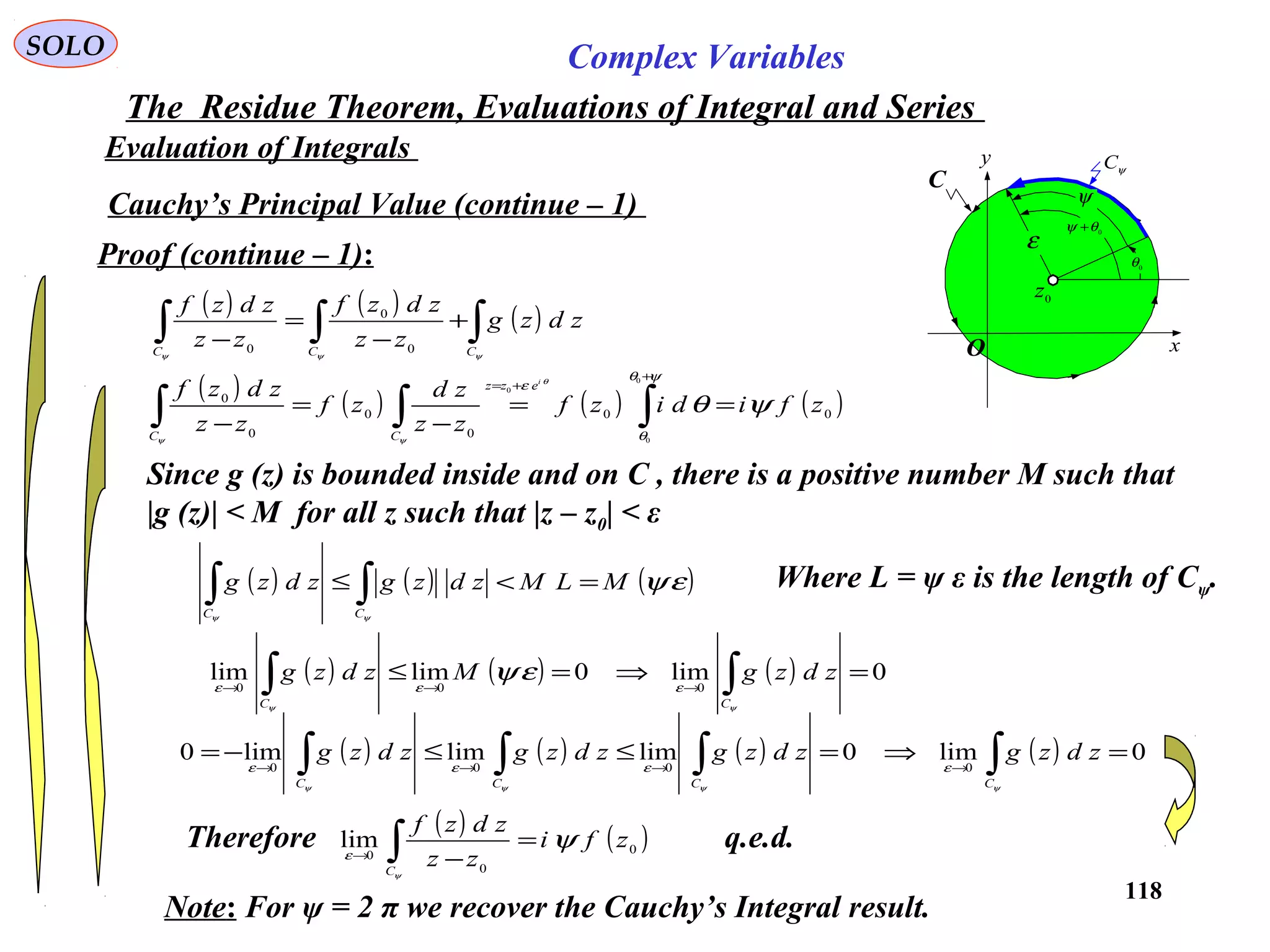

![120

SOLO Complex Variables

The Residue Theorem, Evaluations of Integral and Series

Evaluation of Integrals

Cauchy’s Principal Value (continue – 3)

Theorem 3:

If F (z) is analytic on and inside a positive-sensed curve C, except at the interior poles

zint1, zint2,…, zint n and the simple poles on the curve C, zcont1, zcont2,…, zcont m,

then

Proof:

x

y

1intz

2intz

n

zint

1+scontext

z

2cz

ck

z

1c

ε

2c

ε

0

C

2+scontext

z

1in tcont

z

2intcontz

mcontext

z

scontz int

scontint

ε

mcontext

ε

2intcont

ε

2+scontext

ε

1+scontext

ε

2in tcontCz

2+scontext

Cz

1+scontext

Cz

1in tcont

Cz

mcontext

Cz

scont

Cz in t

∑=

+=

m

k

kcontCCC

1

0

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

+=++ ∑∑∑ ∫∑ ∫∫ ==+==

s

k

kcont

n

j

j

m

sk C

s

k CC

zFReszFResizdzFzdzFzdzF

kextcontkcont

1

int

1

int

11

2

int0

π

( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

+= ∑∑∫ ==

m

k

kcont

n

j

j

C

zFReszFResizdzF

11

int

2

1

2π

Let encircle the simple poles zcont k on the C contour by

semicircles Ccont k of radiuses ε cont k such that,

randomly, zcont int 1,…, zcont int s, are inside the

integration contour, and zcont ext s+1,…,zcont ext m are

outside the integration contour. We have:

where](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-120-2048.jpg)

![121

SOLO Complex Variables

The Residue Theorem, Evaluations of Integral and Series

Evaluation of Integrals

Cauchy’s Principal Value (continue – 4)

Proof (continue – 1):

x

y

1intz

2intz

n

zint

1+scontext

z

2cz

ck

z

1c

ε

2cε

0

C

2+scontext

z

1intcont

z

2intcontz

mcontext

z

scontz int

scontin t

ε

mcontext

ε

2in tcont

ε

2+scontext

ε

1+scontext

ε

2intcontCz

2+scontext

Cz

1+scontext

Cz

1intcont

Cz

mcontext

Cz

scont

Cz int

( ) ( )[ ]

= ∑∑ ∫ ==

→

s

k

kcont

s

k C

zFResizdzF

kcont

kcont

1

int

1

0

int

int

lim πε

The integrals along the semicircles Ccont k of the

singularities zcont ext s+1,…,zcont ext m that are

outside the integration contour, are in the negative

direction, and we have, according to Theorem 2:

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

+== ∑∑∫∫ ==

→

∑

m

k

kcont

n

j

j

CC

zFReszFResizdzFzdzF

c

11

int

0 2

1

2lim

0

π

ε

therefore:

Since the integrals along the semicircles Ccont k of the

singularities zcont int 1,…, zcont int s, that are inside the

integration contour, are in the positive direction we have,

according to Theorem 2:

( ) ( )[ ]

−= ∑∑ ∫ +=+=

→

m

sk

kextcont

m

sk C

zFResizdzF

kextcont

kcont

11

0int

lim πε

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

+=++ ∑∑∑ ∫∑ ∫∫ ==+==

s

k

kcont

n

j

j

m

sk C

s

k CC

zFReszFResizdzFzdzFzdzF

kextcontkcont

1

int

1

int

11

2

int0

π

Note: This result is independent on the way that we encircled the simple poles on

the curve C.

q.e.d.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-121-2048.jpg)

![125

SOLO

Example 2

0,

1

21

2

1

>∫−

RRxd

x

R

R

kLet compute: for k integer and positive

x

y

R

ε

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

Rx =Rx −=

This integral has a singularity on the path of

integration on x = 0:

Complex Variables

( )

( ) ( )[ ]

>

≤<

=+−−+−−=

−−=

+=

−−−−

→

→

−

−

−

−

→

→

−

−→

→

−

∫∫∫

1

100

lim

lim

11

lim

1

1

2

1

2

1

1

1

1

0

0

11

0

0

0

0

2

1

2

2

1

1

2

1

2

2

1

12

1

2

1

kdefinednot

k

kRkRkk

xkxkxd

x

xd

x

xd

x

kkkk

R

k

R

k

R

k

R

k

R

R

k

εε

ε

ε

ε

ε

ε

ε

ε

ε

ε

ε

Let compute:

( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

>

≤<

=

−

−

−+−−+−−=

−+−=

++=

−

−

−−−−

→

−

−

−

−

→

−

−

→

−

∫∫∫∫∫

oddk

k

e

k

kRkRkk

xk

eR

deRi

xkxd

x

zd

z

xd

x

xd

x

ki

k

kkkk

R

k

kik

i

R

k

R

k

C

k

R

k

R

R

k

&10

100

1

1

lim

lim

111

lim

1

2

1

11

2

1

1

1

0

1

0

1

00

2

2

1

1

2

1

2

1

π

ε

ε

π

θ

θ

ε

ε

εε

ε

ε

ε

εε

θ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-125-2048.jpg)

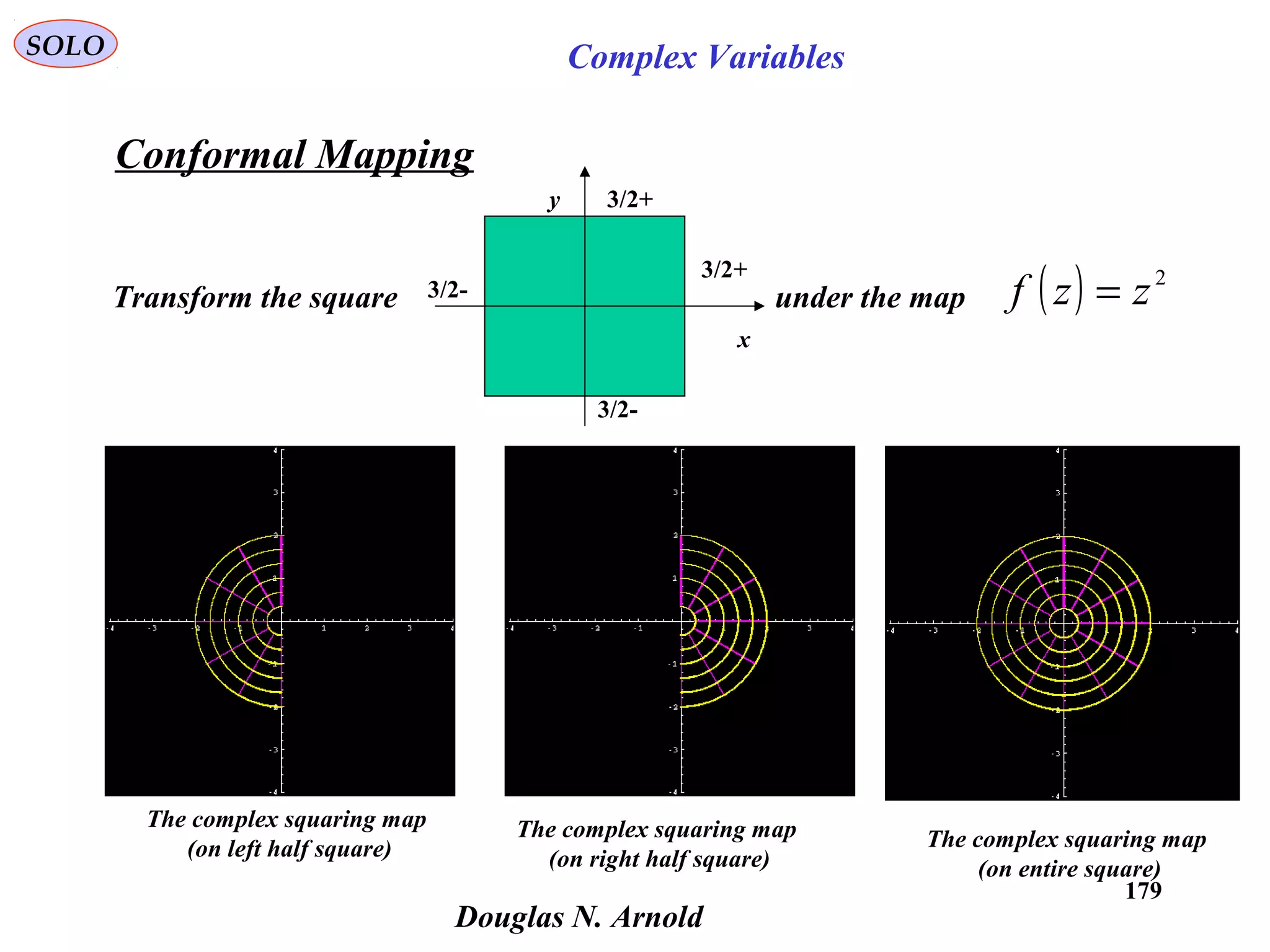

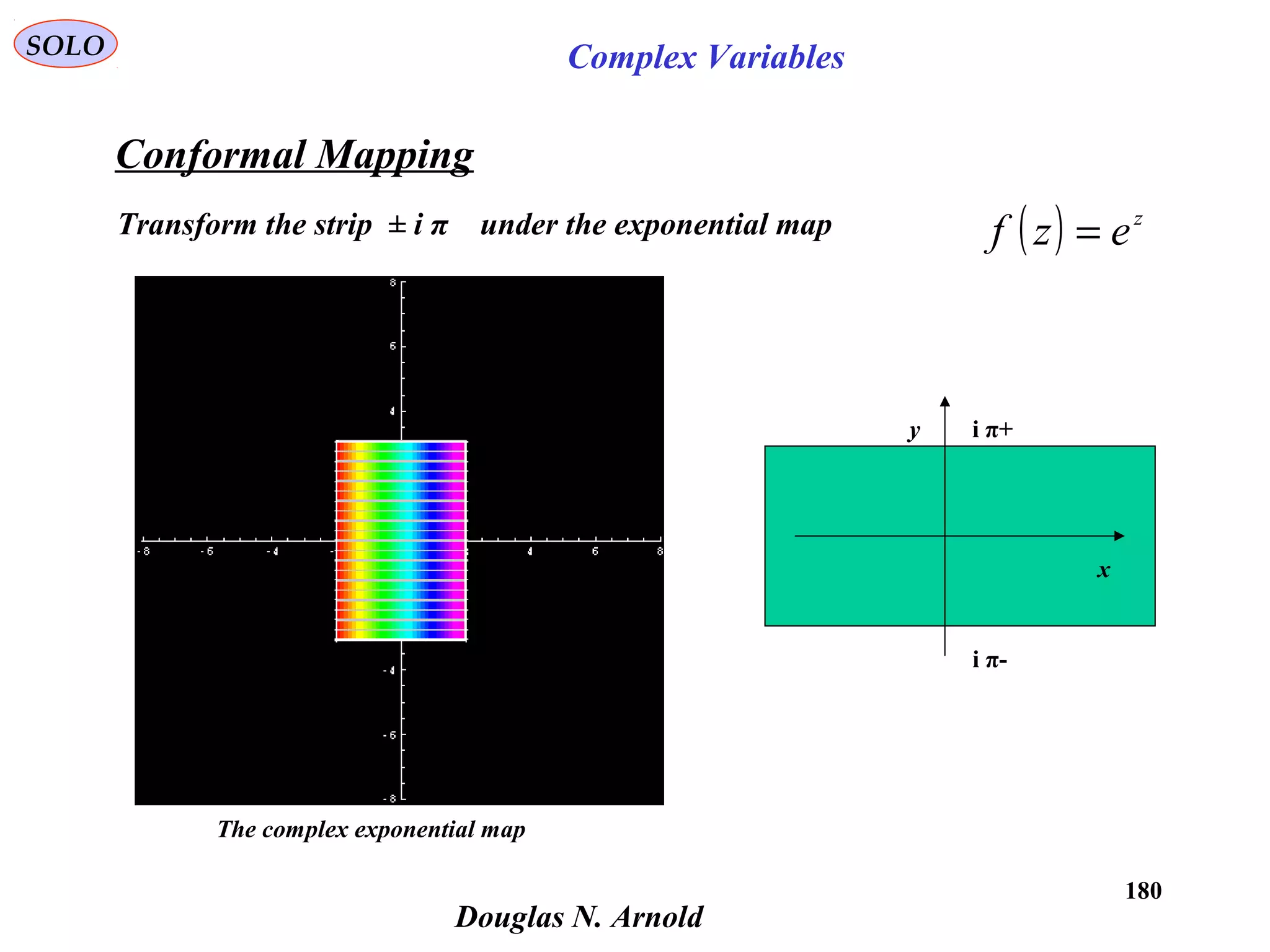

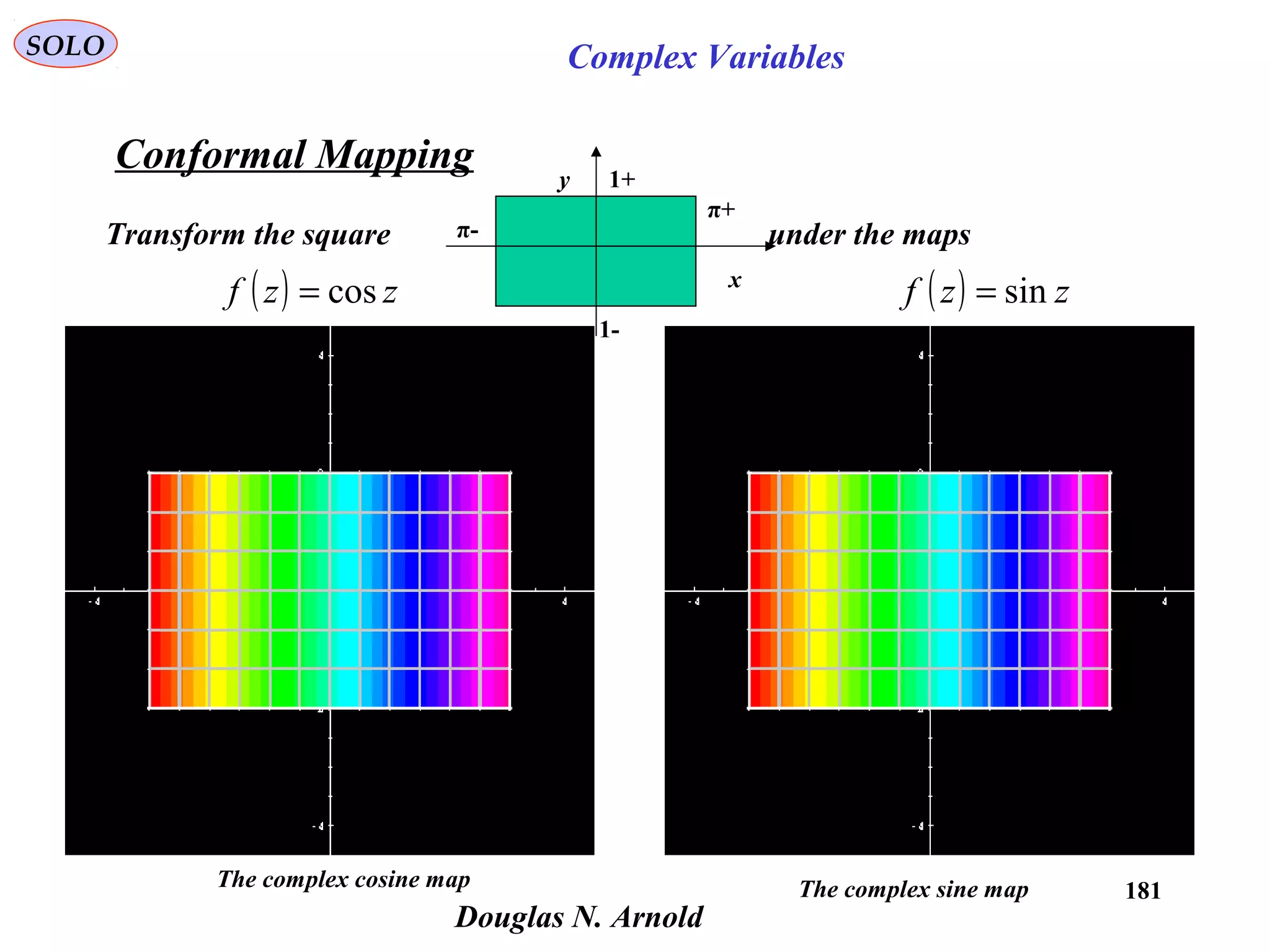

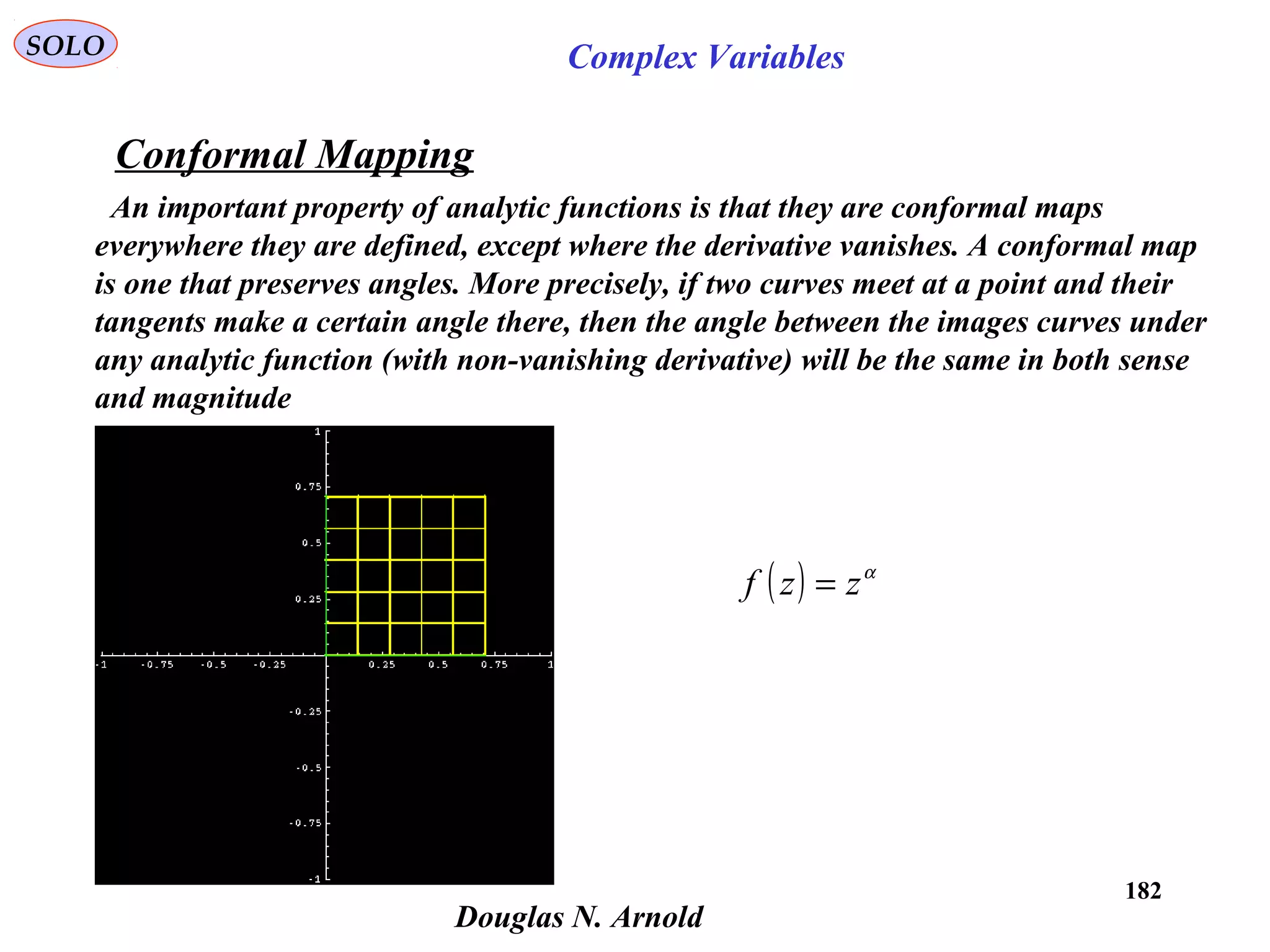

![170

SOLO Complex Variables

Conformal Mapping

( ) ( )[ ] RzRzzzf ≤−±=

2/122

ln

( )

( )

( ) ( )( ) z

Rzz

RzzR

Rzz

Rzz

R

Rzz

w

R

w 2222

2/1222

2/122

2/122

2

2/122

2

=

+−

−

+−±=

−±

+−±=+

Define ( ) ( ) RzRzzzgw ≤−±==

2/122

+=

w

R

w

2

1

z

2

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

−++=

+

++=+

w

w

R

w

w

R

wwiww

2

1

wwiww

R

wwiww

2

1

yix

argsinargcosargsinargcos

argsinargcos

argsinargcos

22

2

( ) ( )

−=

+=

w

R

ww

2

1

y

w

R

ww

2

1

x

22

argsin&argcos](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-170-2048.jpg)

![171

SOLO Complex Variables

Conformal Mapping

( ) ( )[ ] RzRzzzf ≤−±=

2/122

ln

Define ( ) ( ) RzRzzzgw ≤−±==

2/122

( ) ( )

−=

+=

w

R

ww

2

1

y

w

R

ww

2

1

x

22

argsin&argcos

From those equations we have:

( ) ( )

2

2

2

2

2

22

4

1

4

1

argsinargcos

R

w

R

w

w

R

w

w

y

w

x

=

−−

+=

−

4

1

w

R

w

y

w

R

w

x

=

−

+

+

2

2

2

2

x

y

( )warg

wln

( ) ( )wiwzf argln +=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-171-2048.jpg)

![172

SOLO Complex Variables

Conformal Mapping

( ) 2/tt

eex −

+=

0122

=+− tt

exe

( ) ( ) 2/cosh tt

eet −

+=

( ) ( )[ ]2/12

1ln −±= xxxacosh

http://www.mathworks.com/company/newsletters/news_notes/clevescorner/sum98cleve.html](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-172-2048.jpg)

![173

SOLO Complex Variables

Conformal Mapping

( ) ( )[ ]2/122

ln Rzzzf +±=

( )

( )

( ) ( )( ) z

Rzz

RzzR

Rzz

Rzz

R

Rzz

w

R

w 2222

2/1222

2/122

2/122

2

2/122

2

=

−−

+

−+±=

+±

−−±=−

Define ( ) ( ) 2/122

Rzzzgw +±==

−=

w

R

w

2

1

z

2

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

+−+=

+

−+=+

w

w

R

w

w

R

wwiww

2

1

wwiww

R

wwiww

2

1

yix

argsinargcosargsinargcos

argsinargcos

argsinargcos

22

2

( ) ( )

+=

−=

w

R

ww

2

1

y

w

R

ww

2

1

x

22

argsin&argcos](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-173-2048.jpg)

![174

SOLO Complex Variables

Conformal Mapping

( ) ( )[ ]2/122

ln Rzzzf +±=

Define ( ) ( ) 2/122

Rzzzgw +±==

( ) ( )

+=

−=

w

R

ww

2

1

y

w

R

ww

2

1

x

22

argsin&argcos

From those equations we have:

( ) ( )

2

2

2

2

2

22

4

1

4

1

argsinargcos

R

w

R

w

w

R

w

w

y

w

x

−=

+−

−=

−

4

1

w

R

w

y

w

R

w

x

=

+

+

−

2

2

2

2

x

y( )warg

wln

( ) ( )wiwzf argln +=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-174-2048.jpg)

![175

SOLO Complex Variables

Conformal Mapping

http://www.mathworks.com/company/newsletters/news_notes/clevescorner/sum98cleve.html

( ) 2/tt

eex −

−=

0122

=−− tt

exe

( ) ( ) 2/sinh tt

eet −

−=

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]2/12

1ln +±== zzzasinh:zf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-175-2048.jpg)

![176

SOLO Complex Variables

Conformal Mapping

dz

dz

kviuw

+

−

=+= ln

( )

( )

ku

e

ydx

ydx

dz

dz /2

22

222

=

++

+−

=

+

−

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) dx

dyx

ydxydx

ydxydx

e

e

k

u

ku

ku

21

1

coth

222

2222

2222

/2

/2

−

++

=

−+−+−

++++−

=

−

+

=

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )kudkudykudx /sinh/1/coth/coth 222222

=−=++

kvikukviku

ee

dz

dz

ee

dz

dz //// −

∗

∗

=

+

−

→=

+

−

dyi

dyx

i

dzdz

dzz

i

dz

dz

dz

dz

dz

dz

dz

dz

i

ee

ee

i

k

u

ctg kvikvi

kvikvi

2

2222

//

//

−+

=

−

−

=

+

−

−

+

−

+

−

+

+

−

=

−

+

=

∗

∗

∗

∗

∗

∗

−

−

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )kvdkvctgdkvctgdyx /sin/1// 222222

=+=++

kviku

ee

dz

dz //

=

+

−](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-176-2048.jpg)

![177

SOLO Complex Variables

Conformal Mapping

dz

dz

kviuw

+

−

=+= ln

( )[ ] ( )kudykudx /sinh//coth 2222

=++

( )[ ] ( )kvdkvctgdyx /sin// 2222

=++

dd−

x

y

( )[ ] ( )kvdkvctgdyx /sin// 2222

=++

( )[ ] ( )kudykudx /sinh//coth 2222

=++

1v

2

v

3v

3

u

2u

1

u

We have two families of orthogonal circles.

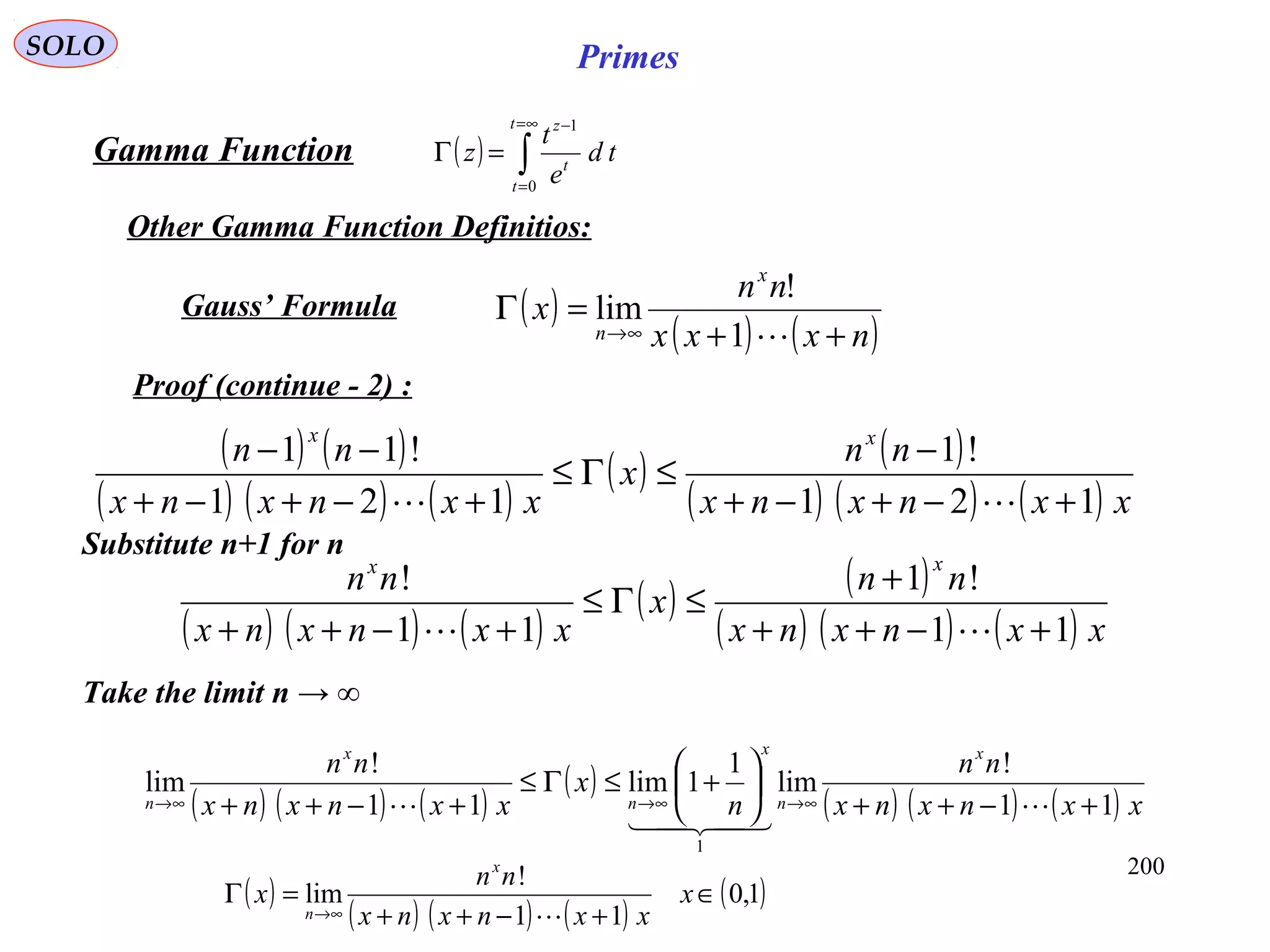

All those circle passe through (-d,0) and (d,0)

v

u](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-177-2048.jpg)

![190

SOLO Primes

( ) ∫

∞=

=

−

=Γ

t

t

t

z

td

e

t

z

0

1

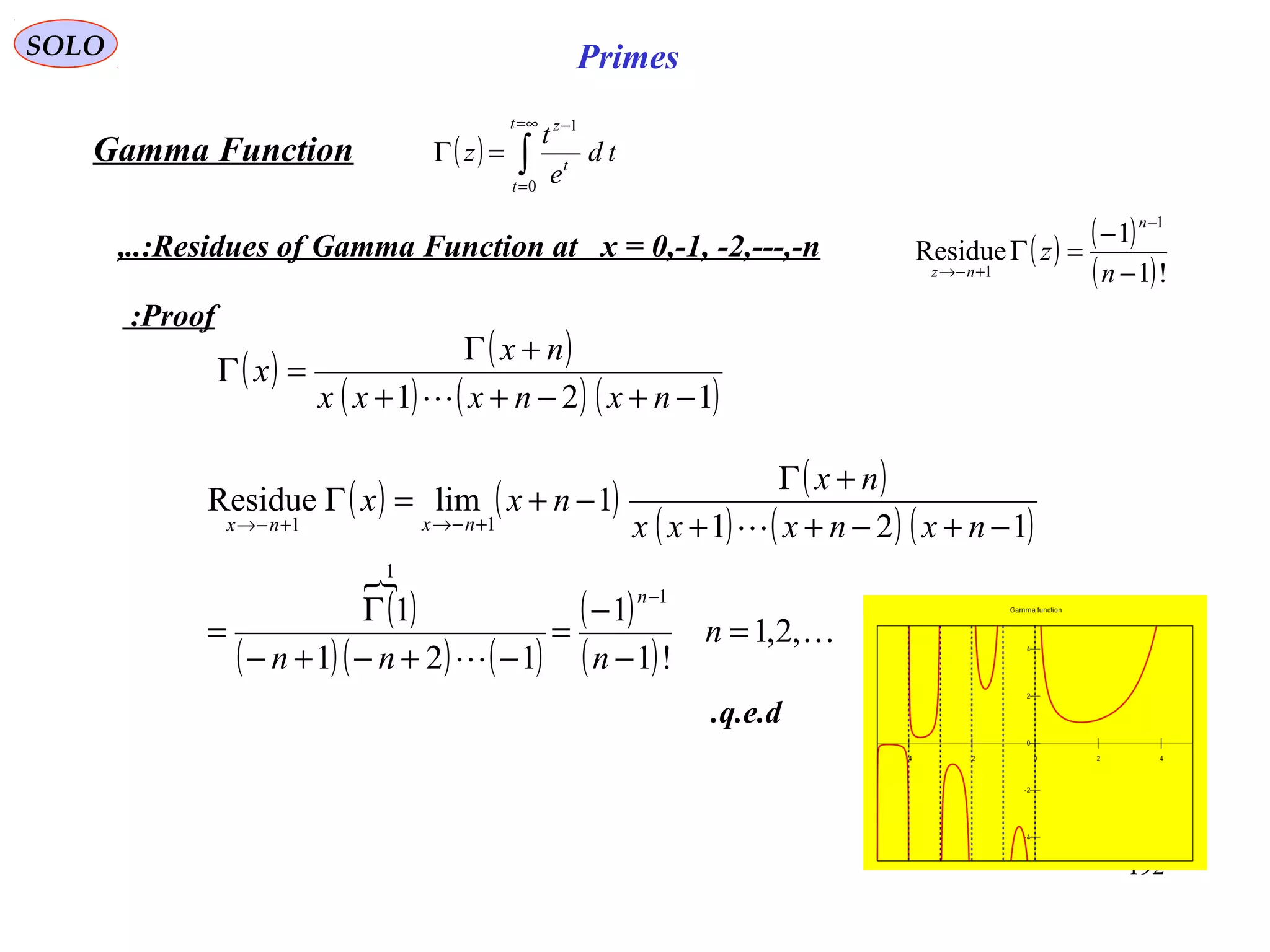

Proof (continue):

Gamma Function

0& >+= xyixz

For the second integral, using integration by parts:

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )( ) ∫

∫∫∫∫

∞=

=

−

∞=

=

−−

=

=

∞=

=

−

∞=

=

−−

=

=

∞=

=

−∞=

=

−+∞=

=

−

−−+−−+=

−+−===

−

−

−

−

t

t

t

x

e

t

t

tx

edv

tu

t

t

t

x

e

t

t

tx

edv

tu

t

t

t

xt

t

t

yixt

t

t

z

td

e

t

xxetx

e

td

e

t

xettd

e

t

td

e

t

td

e

t

t

x

t

x

1

3

/1

1

2

1

2

/1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

211

1

1

2

1

After [x] (the integer defined such that x-[x] < 1) such integration the power of t in

the integrand becomes x-[x]-1 < 0. and we have:

( )( ) [ ]( ) [ ]( ) ( )( ) [ ]( ) ∞<−−−<−−− ∫∫

∞=

=

∞=

=

−−

t

t

t

t

t

txx

td

e

xxxxtd

et

xxxx

11

1

1

21

1

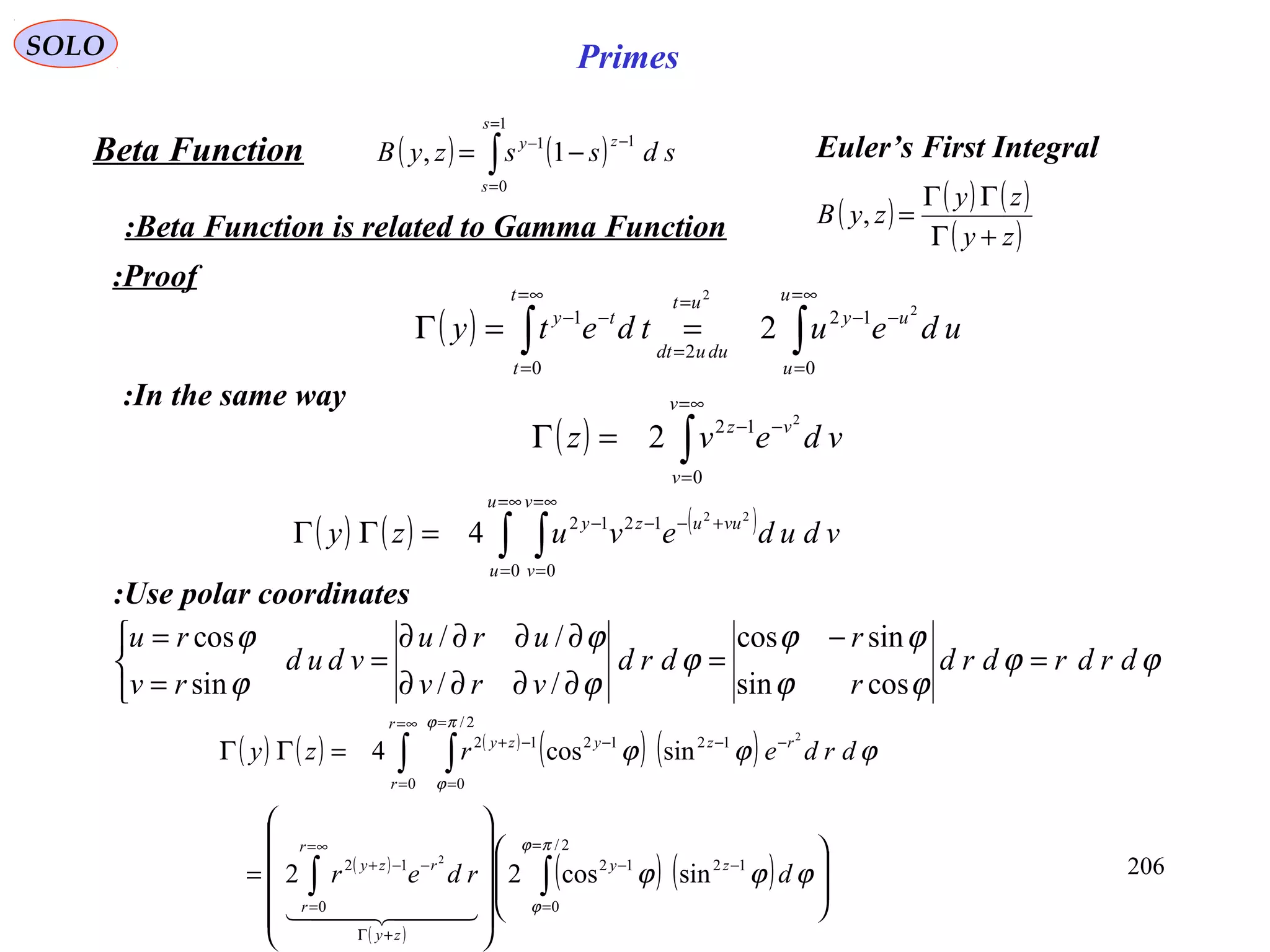

21

Therefore the Gamma integral is defined, and converges uniformly for x > 0.

Gamma integral is defined, and

converges uniformly for x > 0.

q.e.d.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-190-2048.jpg)

![195

SOLO Primes

Second definition identical to First

( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )bayxallyfxfyxf ,,1,011 ∈∈−+≤−+ λλλλλ

Convex Function:

A Function f (x) is called Convex in an interval (a,b) if for every x,y (a,b) we haveϵ

A Function f (x), defined for x > 0, is called Convex, if the corresponding function

( ) ( ) ( )

y

xfyxf

y

−+

=φ

defined for all y > -x, y ≠ 0, is monotonic Increasing throughout the range of

definition.

If 0 < x1 < x < x2, are given by choosing y1 = x1 – x < 0, y2 = x2 – x > 0, we express

the condition of convexity as

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

xx

xfxf

y

xx

xfxf

y

−

−

=≤

−

−

=

2

2

2

1

1

1 φφ

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )xxxfxfxxxfxf −−≥−− 1221

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

( )

λλ −

−

−

+

−

−

≤

1

12

1

2

12

2

1

xx

xx

xf

xx

xx

xfxf

One other equivalent definition:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-195-2048.jpg)

![196

SOLO Primes

( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )1,0ln1ln1ln ∈−+≤−+ λλλλλ yfxfyxf

Logarithmic Convex Function :

A Function f (x)>0 is called logarithmic-convex or simply log-convex if ln (f (x) )

is convex or

This is equivalent to ( )[ ] ( ) ( )( )λλ

λλ

−

≤−+

1

ln1ln yfxfyxf

Since the logarithm is a momotonic increasing function we obtain

( )[ ] ( ) ( )( )

( ) yxyfxfyxf <∈≤−+

−

,1,01

1

λλλ

λλ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-196-2048.jpg)

![197

SOLO Primes

( ) ∫

∞=

=

−

=Γ

t

t

t

z

td

e

t

z

0

1

Proof :

Gamma Function

0& >+= xyixz

( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )1,0ln1ln1ln ∈Γ−+Γ≤−+Γ λλλλλ baba

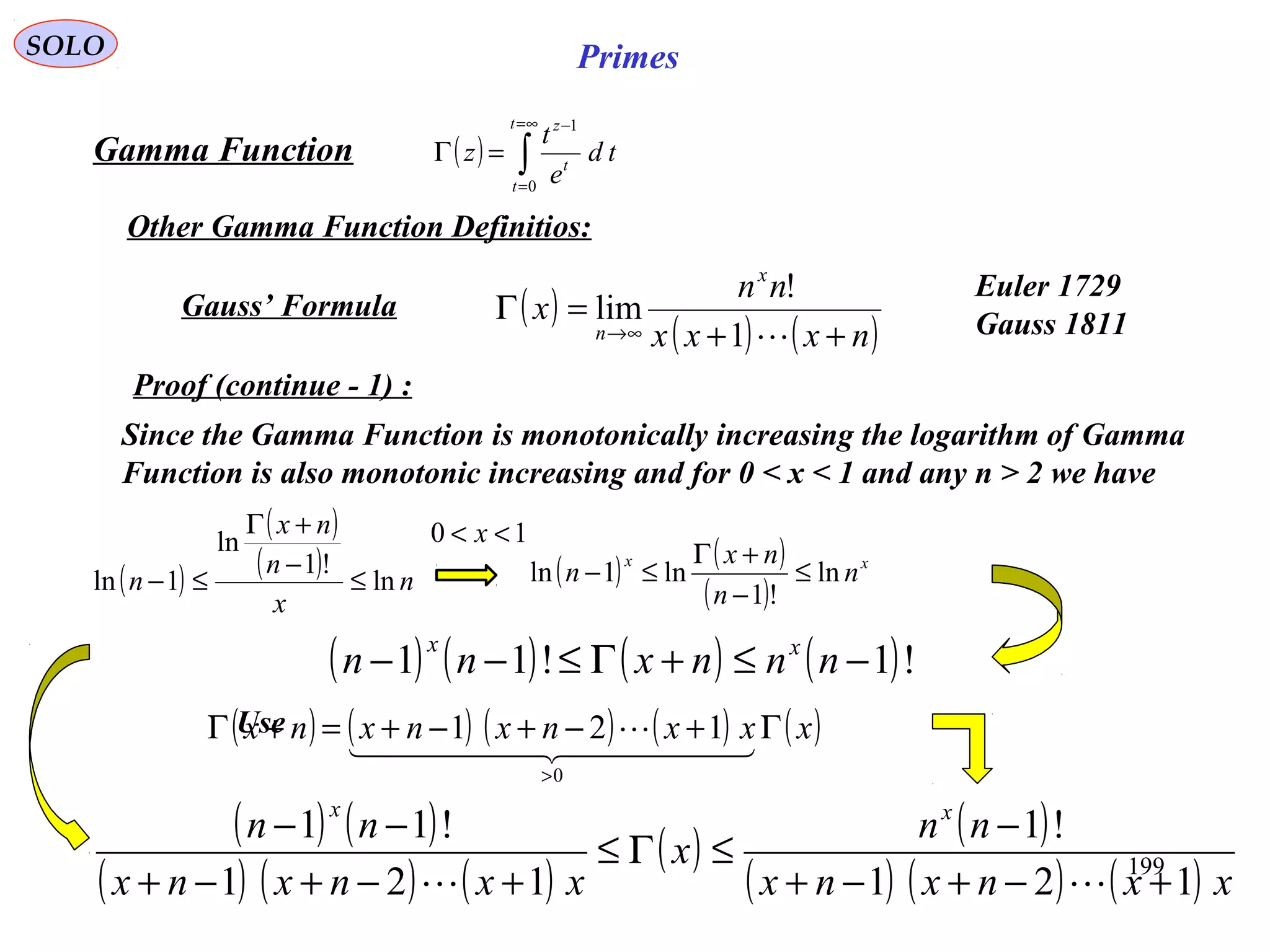

Properties of Gamma Function :

3

Gamma is a

Log Convex

Function

( )[ ] ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) λλ

λλ

λλλλ

λλ

−

−∞

−−

∞

−−

∞

−−−−−

∞

−−−+

ΓΓ=

≤

==−+Γ

∫∫

∫∫

1

1

0

1

0

1

0

111

0

11

1

badtetdtet

dtetetdtetba

tbta

InequalityHolder

tbtatba

q.e.d.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-197-2048.jpg)

![198

SOLO Primes

( ) ∫

∞=

=

−

=Γ

t

t

t

z

td

e

t

z

0

1

Proof :

Gamma Function

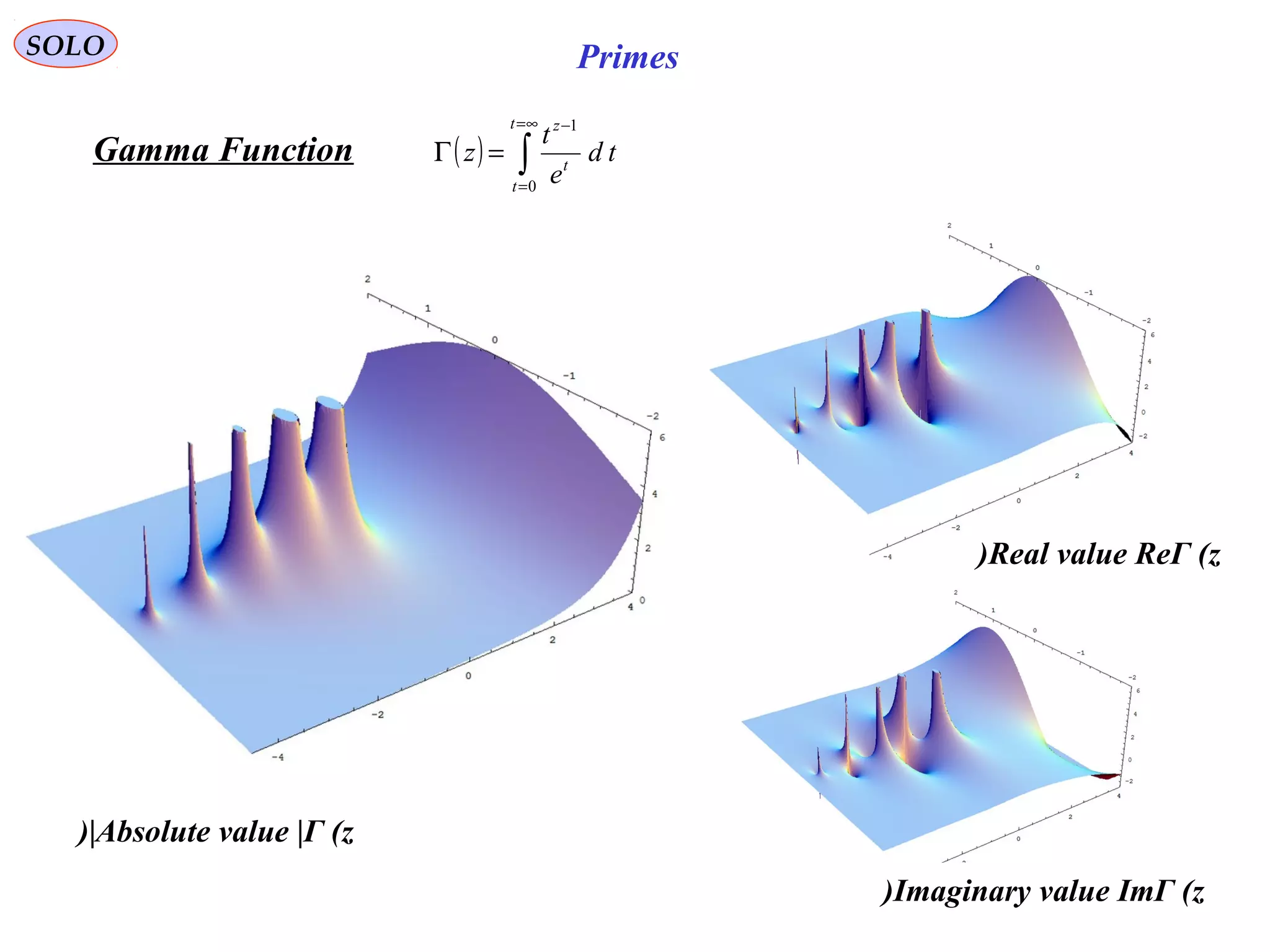

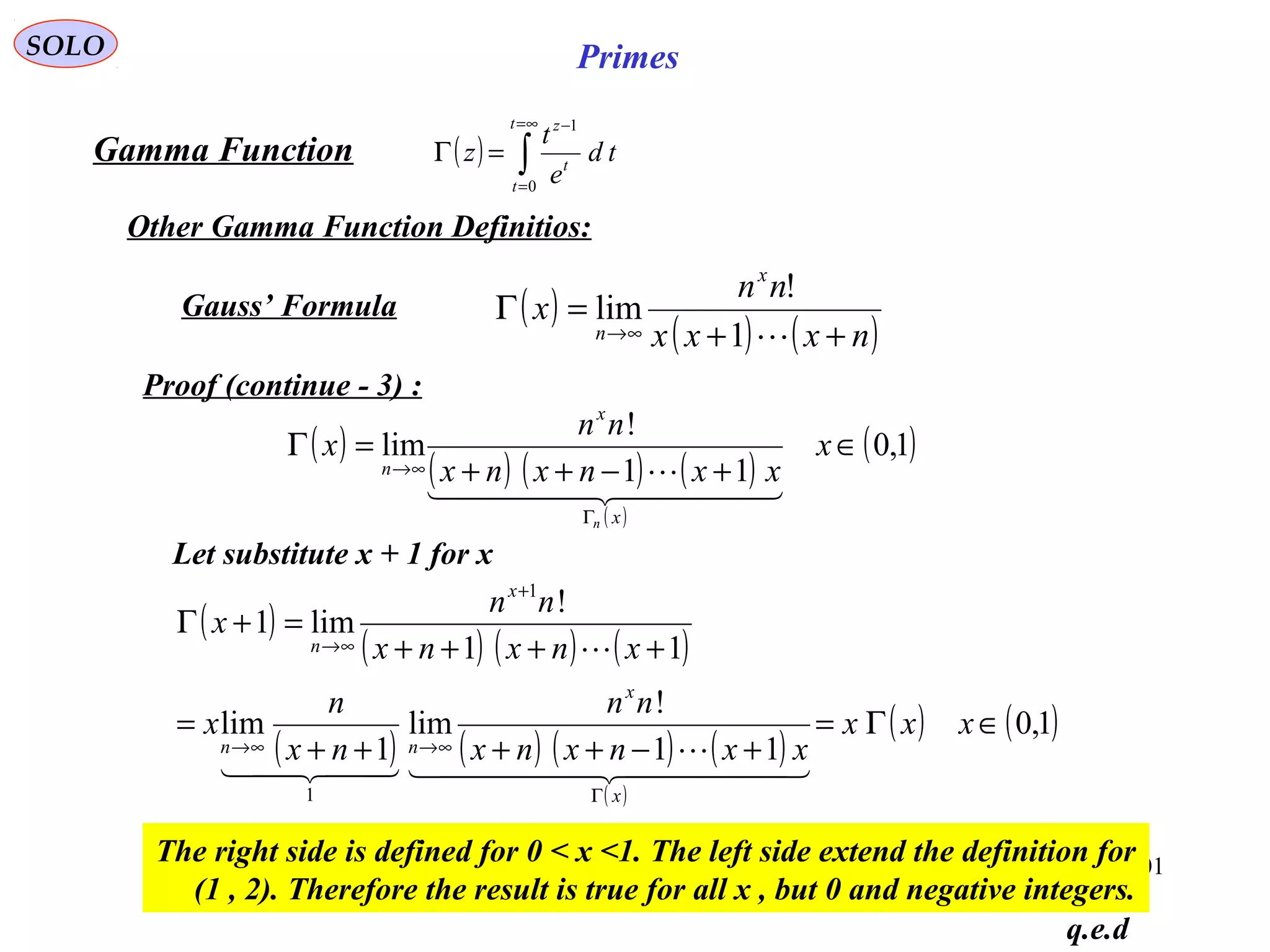

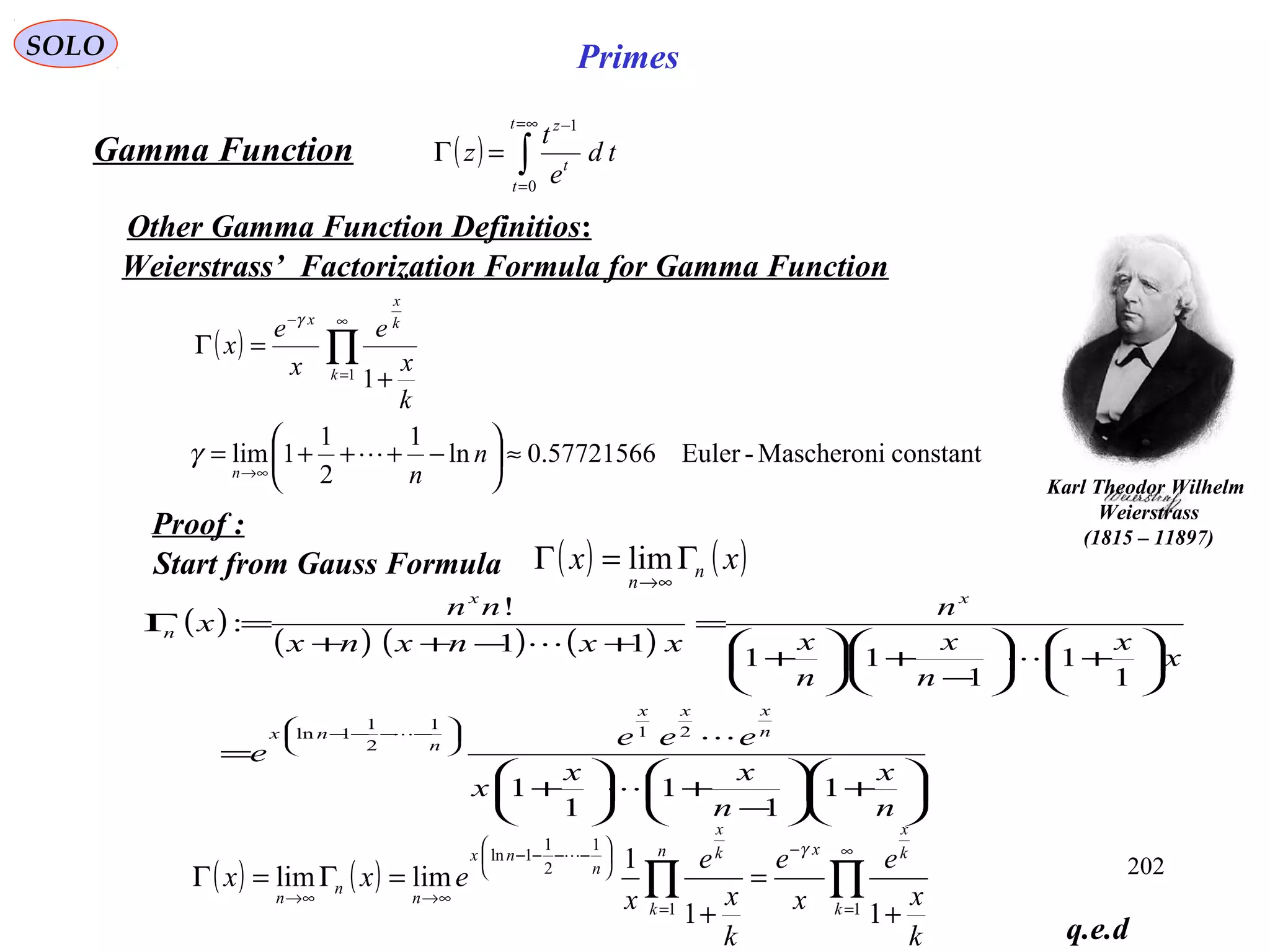

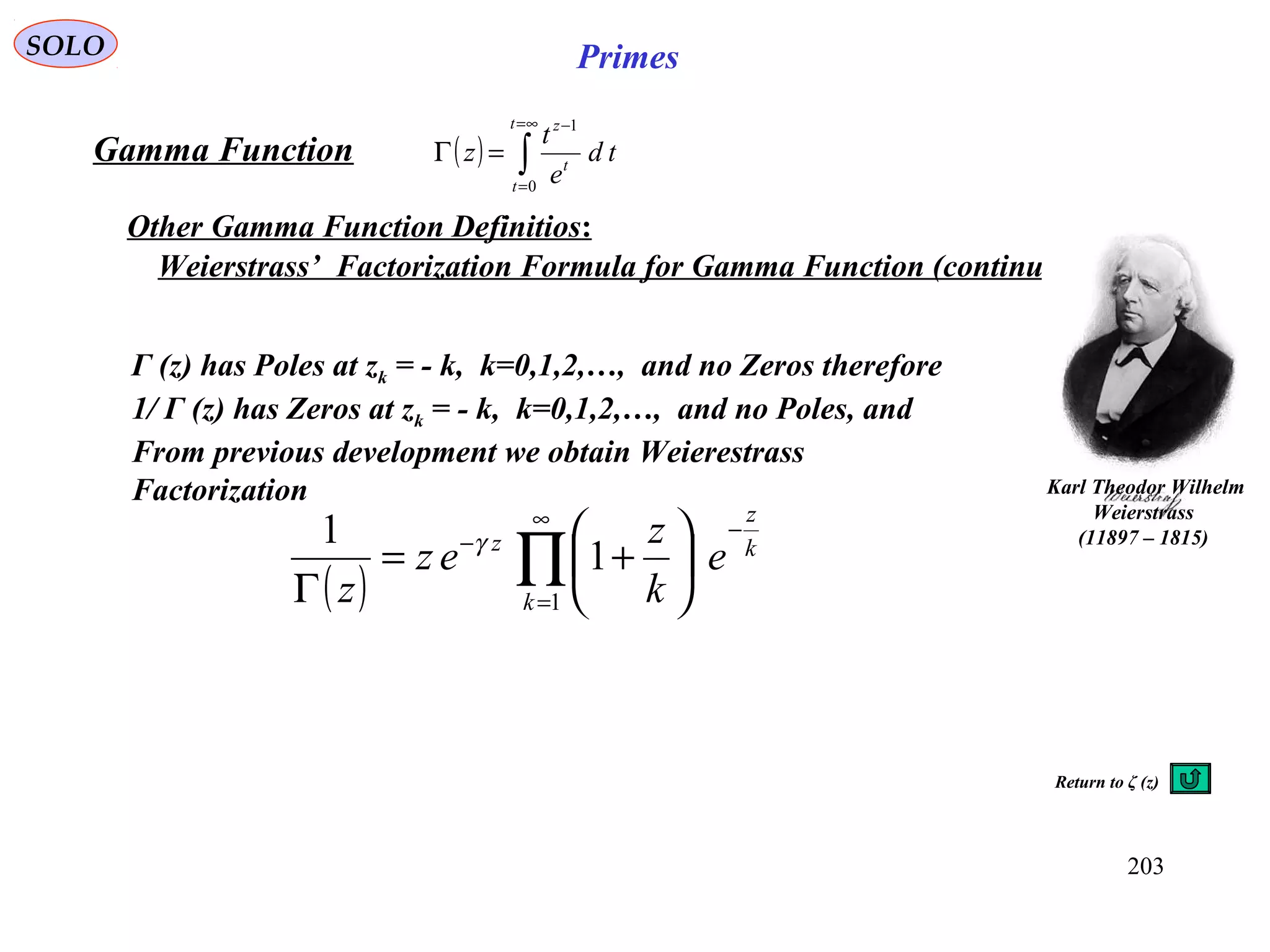

Other Gamma Function Definitios:

( )

( ) ( )nxxx

nn

x

x

n ++

=Γ

∞→ 1

!

limGauss’ Formula

Since the Gamma Function is monotonically increasing the logarithm of Gamma

Function is also monotonic increasing and for 0 < x < 1 and any n > 2 we have

( ) ( )

( ) nnx

nnx

−+

Γ−+Γ lnln

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )

( )

( ) ( )[ ] [ ] ( )[ ]

( )

−

−

−

−−

≤

−−+Γ

≤

−

−−−

!1

!

ln

!2

!1

ln

1

!1ln!ln!1lnln

1

!1ln!2ln

n

n

n

n

nn

x

nnxnn

( )

( )

( ) n

x

n

nx

n ln

!1

ln

1ln ≤

−

+Γ

≤−

( ) ( )

( )

1

1

ln1ln −=←

≤

−+−

Γ−+−Γ x

nn

nn ( ) ( )

( ) nn

nnx

−+

Γ−+Γ

≤

→=

1

ln1ln1

Carl Friedrich Gauss

(1777 – 1855)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-198-2048.jpg)

![212

SOLO Primes

Proof (continue - 3)

( ) ∫

∞=

=

−

=Γ

t

t

t

z

td

e

t

z

0

1

Gamma Function

Other Gamma Function Properties:

yi

y

iy

y

eiud

u

u

eud

u

u ππ

π −

∞ −

−

∞ −

=

+

−

+ ∫∫ 2

11 0

2

0

We obtain

Multiply both sides by yi

e π+

( ) iud

u

u

ee

y

iyiy

πππ

2

10

=

+

− ∫

∞ −

−

( ) ( )yee

i

ud

u

u

iyiy

y

π

π

π ππ

sin

2

10

=

−

=

+ −

∞ −

∫Rearranging we obtain

Since both sides of this equation are Holomorphic (analytic) in x (0,1) we canϵ

extend the result for all analytic parts of z C (complex planeϵ).

( ) ( )

( )[ ] ( )

( )1,0

sin1sin11

1

0

1

0

1

∈=

−

=

+

=

+

=−ΓΓ ∫∫

∞=

=

−−=∞=

=

−

x

xx

ud

u

u

ud

u

u

xx

u

u

yxyu

u

x

π

π

π

π

Substituting y = 1 – x we obtain

( ) ( )

( )z

zz

π

π

sin

1 =−ΓΓ Euler

Reflection Formula](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-212-2048.jpg)

![233

SOLO

Proof (continue – 2): 0& >+= xyixz

( ) ∫∫∫

∞=

=

−=

+=

−∞=

=

−

−

+

−

=

−

=

++Γ

t

t

t

zt

t

t

zt

t

t

z

zz

td

e

t

td

e

t

td

e

t

z

φ

φ

ln2

1ln2

0

1

0

1

1112

1

1

1

In the second integral we have

This integral converges only for x > 1, therefore we proved that

φln21 2/

≥≥− tforee tt

since RatioGoldeneforee ttt

==

+

≥≥−− φ

2

51

01 2/2/

( ) ( )( ) ∫∫∫∫

∞=

=

−

∞

=

−−

=

=

∞=

=

−∞=

=

−+=∞=

=

−

−−−−=≤

−

=

−

−

−

t

t

t

x

termfinite

t

tx

tu

dtedv

t

t

t

xt

t

t

xiyxzt

t

t

z

td

e

t

xettd

e

t

td

e

t

td

e

t

x

t

φ

φ

φφφ ln2

2/

2

ln2

2/1

ln2

2/

1

ln2

1

ln2

1

122

11

1

2/

( ) [ ]

( )( ) [ ]( ) [ ]( ) ∞<−−−−−= ∫∑∫

∞=

=

−−

−

∞=

=

−

finite

t

t

txx

xx

t

t

t

x

td

et

xxxxtermsfinitetd

e

t

φφ ln2

2/1

ln2

2/

1

1

212

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 1Re

12

1

1

1

0

1

>=∞<

−

=Γ=

++Γ ∫

∞=

=

−

zxfortd

e

t

zzz

t

t

t

z

zz

ς

( ) ( ) ( ) 1Re

10

1

>=∞<

−

=Γ ∫

∞=

=

−

zxfordt

e

t

zz

t

t

t

z

ς

After [x] (the integer defined such that x-[x] < 1) such integration the power of t in

the integrand becomes x-[x]-1 < 0. and we have:

q.e.d.

Riemann's Zeta Function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-233-2048.jpg)

![235

SOLO

Proof (continue – 1)

The first integral can be written as

εi−∞

εi+∞

y

x

εε i+

εε i−

2ε

( ) ( )[ ] ( )

∫∫∫∫

∞=

+=

−

−

−=+=

∞=

−

−−

=

∞=

−

−−

→

−=−=

−∞=

−

→ −

=

−

=

−

−

=

−

−

− t

t

t

z

zi

et

t

t

z

zi

t

t

it

ziiti

i

z

td

e

t

etd

e

t

etd

e

eit

d

e

i

0

110 1

1

1

0

0 1

0 111

lim

1

lim ππ

ε

ε

π

ε

ελεελ

ελ

λε

π

ε

λ

λ

The second integral can be written as

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) 0

1

2

lim2

1

2

lim

2

1

2

lim

1

lim

2

0

20

2

0

2

1

0

2

0

2

1

0

21

0

→

−

=

−

−

≤

−

−

=

−

−

∫∫

∫∫

=

=

→

=

=

−+

→

=

=

−+

→

=+=

−=

−

→

πθ

θ

εε

πθ

θ

θ

ε

θ

ε

πθ

θ

θ

ε

θ

ε

ελεελ

εελ

λε

θ

ε

θε

ε

θε

ε

λ

λ

θθ

θ

θ

d

e

dei

e

e

dei

e

e

d

e

ii

i

i

e

x

i

e

iyxi

i

e

iyxie

originaroundCircle

i

i

z

( )

( ) ( )

( )

00

1sin2

1

0

0

1

itoreturnsandzeroencirclesiatstartspaththe

d

e

i

zz

z

i

i

z

+∞−∞

−

−

Γ

= ∫

+∞=

−∞=

−λ

λ

λ

λ

λ

π

ς

Riemann's Zeta Function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-235-2048.jpg)

![236

SOLO

Proof (continue – 2)

The third integral can be written as

εi−∞

εi+∞

y

x

εε i+

εε i−

2ε

( ) ( )[ ] ( )

∫∫∫∫

∞=

+=

−−=∞=

+=

−

−

∞=

=

+

−

→

+=+∞=

+=

−

→ −

−=

−

=

−

+

=

−

−

− t

t

t

z

zi

et

t

t

z

zi

t

t

it

ziiti

i

z

td

e

t

etd

e

t

etd

e

eit

d

e

i

0

11

0

1

1

1

0

1

0 111

lim

1

lim ππ

ε

ε

π

ε

ελελ

εελ

λε

π

ε

λ

λ

Therefore

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ∫∫∫∫

∞=

+=

−∞=

+=

−−∞=

+=

−

−

+∞=

−∞=

−

−

−=

−

−

−=

−

−=

−

−

t

t

t

zt

t

t

zzizit

t

t

z

zizi

i

i

z

td

e

t

zitd

e

t

i

ee

itd

e

t

eed

e 0

1

0

1

0

10

0

1

1

sin2

12

2

11

πλ

λ ππ

ππ

λ

λ

λ

But we found that ( ) ( ) ( ) 1Re

10

1

>=∞<

−

=Γ ∫

∞=

=

−

zxfordt

e

t

zz

t

t

t

z

ς

( )

( ) ( )

( )

00

1sin2

1

0

0

1

itoreturnsandzeroencirclesiatstartspaththe

d

e

i

zz

z

i

i

z

+∞−∞

−

−

Γ

= ∫

+∞=

−∞=

−λ

λ

λ

λ

λ

π

ς

Therefore ( )

( ) ( )

( )

∫

+∞=

−∞=

−

−

−

Γ

=

0

0

1

1sin2

1

i

i

z

d

e

i

zz

z

λ

λ

λ

λ

λ

π

ς

The right hand is analytic for any z ≠ 1. Since it equals Zeta Function in the half

plane x > 1, it is the Analytic Continuation of Zeta to the complax plane for any z ≠ 1.

( )

( ) ( )

( )

∫

+∞=

−∞=

−

−

−

Γ

=

0

0

1

1sin2

1

i

i

z

d

e

i

zz

z

λ

λ

λ

λ

λ

π

ς q.e.d.

Riemann's Zeta Function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-236-2048.jpg)

![238

SOLO

Proof (continue)

( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞=

−∞=

−

−

−=

−

−

0

0

1

1

2

sin22

1

i

i

z

z

z

z

id

e

λ

λ

λ

ς

π

πλ

λ

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ∑∑∑∫

∞

=

−

−−

∞

=

−

∞

=

−

+∞

−∞

−

+−=+−=

−

−

1

1

11

1

1

1

1

0

0

1

1

22222

1 n

z

zzz

n

z

n

z

i

i

z

n

iiiniiniid

e

πππππλ

λ

λ

( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )

[ ] ( ) ( )

[ ]

−=−=−=−−=+− −−−−

2

sin22/2/lnln11 z

eeieeiiiiiii izizizizzzzz πππ

( )z

nn

z

−=∑

∞

=

−

1

1

1

1

ς

( ) ( ) ( )z

z

id

e

z

i

i

z

−

−=

−

−

∫

+∞

−∞

−

1

2

sin22

1

0

0

1

ς

π

πλ

λ

λ

q.e.d.

Riemann's Zeta Function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-238-2048.jpg)

![242

SOLO

Proof

Start from

use

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )z

z

zzz

z

−

=Γ 1

2

sin22sin2 ς

π

πςπ

( ) ( )

( )z

zz

π

π

sin

1 =−ΓΓ

( ) ( )

( )z

zz

−Γ

=Γ

1

sin

π

π

−Γ

Γ

=

2

1

2

2

sin

zz

z π

π

z

z

→

2

( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( )z

z

zz

z

z

z

−

−ΓΓ

=

−Γ

1

2

sin

2/12/

1

2

1

1

ς

π

πς

or

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )z

z

zzz zzz

−

−Γ

−Γ=Γ −−−

1

2/1

1

122/ 2/12/12/

ςππςπ

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )[ ] ( )

( )

z

z

z

z

zzzz

−

−−−

−−Γ=Γ

1

2/12/

12/12/

ηη

ςπςπ

Riemann's Zeta Function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-242-2048.jpg)

![243

SOLO

Proof (continue)

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )[ ] ( )

( )

z

z

z

z

zzzz

−

−−−

−−Γ=Γ

1

2/12/

12/12/

ηη

ςπςπ

or

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )z

z

zzz zzz

−

−Γ

−Γ=Γ −−−

1

2/1

1

122/ 2/12/12/

ςππςπ

( )

+

Γ

Γ=Γ −−

2

1

2

2 12/1 zz

z z

π

( ) ( )2/1

2

1

21 2/1

z

z

z z

−Γ

−

Γ=−Γ −−

π z

z

−

↓

1

( )

( )

−

Γ=

−Γ

−Γ

2

1

2/1

1

122/1 z

z

zz

π

therefore

q.e.d.

( ) ( ) ( )

( )z

z

zz zz

−

−

Γ=Γ −−−

1

2

1

2/ 2/12/

ςπςπ

Use Legendre

Duplication Formula: ( ) ( ) 0Re2

22

1

12

>Γ=

+ΓΓ −

zzzz z

π

2/z

z

↓

Riemann's Zeta Function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-243-2048.jpg)

![246

SOLO

Zeta Function Values and the Bernoulli Numbers

We found

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )

( )

2/1

12

2/1

1

2/1

!12

!121

224212531

121221

12531

21

2/1

π

ππ

⋅

−

−⋅−

=

⋅

−⋅⋅−⋅⋅

−⋅⋅⋅−

=

−⋅⋅

−

=+−Γ

−

−

m

m

mm

m

m

m

mm

mmmmm

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

,3,2,1

2/1!2

!121

21 2

2/112

=

+−Γ

−−

=−

−

mB

mm

m

m m

mm

π

ςTherefore

Finally

( ) ( )

( )

,2,1,0

1

1 1

=

+

−−=− +

n

n

B

n nn

ς

( ) ,3,2,1

2

1

21 2 ==− mB

m

m mς

We also found The two expressions

Agree.

Riemann Zeta Function

Riemann's Zeta Function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-246-2048.jpg)

![Fourier Transform

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−== dttjtftfF ωω exp:F

SOLO

Jean Baptiste Joseph

Fourier

1768 - 1830

F (ω) is known as Fourier Integral or Fourier Transform

and is in general complex

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]ωφωωωω jAFjFF expImRe =+=

Using the identities

( ) ( )t

d

tj δ

π

ω

ω =∫

+∞

∞− 2

exp

we can find the Inverse Fourier Transform ( ) ( ){ }ωFtf -1

F=

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]00

2

1

2

exp

2

expexp

2

exp

++−=−=−=

−=

∫∫ ∫

∫ ∫∫

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

tftfdtfd

d

tjf

d

tjdjf

d

tjF

ττδττ

π

ω

τωτ

π

ω

ωττωτ

π

ω

ωω

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

==

π

ω

ωωω

2

exp:

d

tjFFtf -1

F

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]00

2

1

++−=−∫

+∞

∞−

tftfdtf ττδτ

If f (t) is continuous at t, i.e. f (t-0) = f (t+0)

This is true if (sufficient not necessary)

f (t) and f ’ (t) are piecewise continue in every finite interval1

2 and converge, i.e. f (t) is absolute integrable in (-∞,∞)( )∫

+∞

∞−

dttf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-249-2048.jpg)

![Fourier TransformSOLO

( )tf

-1

F

F

( )ωFProperties of Fourier Transform

Linearity1

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )ωαωαωαααα 221122112211 exp: FFdttjtftftftf +=−+=+ ∫

+∞

∞−

F

Symmetry2

( )tF

-1

F

F

( )ωπ −f2

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ){ }tFdttjtFf

dt

tjtFf

d

tjFtf

t

F=−=−⇒=⇒= ∫∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

↔

+∞

∞−

ωωπ

π

ωω

π

ω

ωω

ω

exp2

2

exp

2

exp

Proof:

Conjugate Functions3

( )tf *

-1

F

F

( )ω−*

F

Proof:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ){ }tf

d

tjF

d

tjFtf ****

2

exp

2

exp 1-

F=−=−= ∫∫

+∞

∞−

→−

+∞

∞−

π

ω

ωω

π

ω

ωω

ωω](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-250-2048.jpg)

![Fourier TransformSOLO

( )tf

-1

F

F

( )ωFProperties of Fourier Transform

Modulation9

Shifting: for any a real8

Proof:

( ) ttf 0cos ω -1

F

F

( ) ( )[ ]00

2

1

ωωωω −++ FF

Proof:

( ) ( )[ ]tjtjt 000 expexp

2

1

cos ωωω −+=

( )atf −

-1

F

F ( ) ( )ωω ajF −exp ( ) ( )tajtf exp

-1

F

F ( )aF −ω

( ){ } ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( )ωωττωτω

τ

Fajdajfdttjatfatf

at

−=+−=−−=− ∫∫

+∞

∞−

=−

+∞

∞−

expexpexp:F

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( )aFdttajtfdttjtajtftajtf −=−−=−= ∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

ωωω expexpexp:expF

use shifting property with a=±ω0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-255-2048.jpg)

![( )atf −

-1

F

F ( ) ( )ωω ajF −exp

Fourier TransformSOLO

( )tf

-1

F

F

( )ωFProperties of Fourier Transform (Summary)

Linearity1

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )ωαωαωαααα 221122112211 exp: FFdttjtftftftf +=−+=+ ∫

+∞

∞−

F

Symmetry2

( )tF

-1

F

F

( )ωπ −f2

Conjugate Functions3 ( )tf *

-1

F

F

( )ω−*

F

Scaling4 ( )taf

-1

F

F

a

F

a

ω1

Derivatives5 ( ) ( )tftj

n

−

-1

F

F ( )ω

ω

F

d

d

n

n

( )tf

td

d

n

n

-1

F

F

( ) ( )ωω Fj

n

Convolution6

( ) ( )tftf 21

-1

F

F ( ) ( )ωω 21

* FF( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−= τττ dtfftftf 2121

:*

-1

F

F ( ) ( )ωω 21

FF

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

= ωωω

π

dFFdttftf 2

*

12

*

1

2

1

Parseval’s Formula7

Shifting: for any a real8

( ) ( )tajtf exp

-1

F

F ( )aF −ω

Modulation9 ( ) ttf 0

cos ω -1

F

F

( ) ( )[ ]00

2

1

ωωωω −++ FF

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

−=−= ωωω

π

ωωω

π

dFFdFFdttftf 212121

2

1

2

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-256-2048.jpg)

![( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−== dttjtftfF νπνπ 2exp:2 F

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

∞

=

−

+∞

−∞=

=

+=

0

* 21

n

nsT

n

eTnf

T

n

jsF

T

sF

π

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

== ννπνπνπ dtjFFtf 2exp2:2-1

F

SOLO

Sampling and z-Transform (continue – 5)

We found

Using the definition of the Fourier Transform and it’s inverse:

we obtain ( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

= ννπνπ dTnjFTnf 2exp2

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑∫∑

∞

=

+∞

∞−

∞

=

−=−=

0

111

0

*

exp2exp2exp

nn

n

sTndTnjFsTTnfsF ννπνπ

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]∫ ∑

+∞

∞−

+∞

−∞=

−−== 111

*

2exp22 νννπνπνπ dTnjFjsF

n

( ) ( ) ∑∫ ∑

+∞

−∞=

+∞

∞−

+∞

−∞=

−=

−−==

nn T

n

F

T

d

T

n

T

FjsF νπνννδνπνπ 2

11

22 111

*

We recovered (with –n instead of n) ( ) ∑

+∞

−∞=

+=

n T

n

jsF

T

sF

π21*

Second Way (continue)

Making use of the identity: with 1/T instead of T

and ν - ν 1 instead of t we obtain: ( )[ ] ∑∑

−−=−−

nn T

n

T

Tnj 11

1

2exp ννδννπ

( )∑∑ −=

−

nn

TntT

T

tn

j δπ2exp

Z Transform](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-267-2048.jpg)

![Z TransformSOLO

Table of Z-Transform Functions

Z - Domain

k - Domain

( )kf ( ) ( ) f

k

k

RzzkfzF >= ∑

∞

=

−

0

1

( )mkf + ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]110 11

−−−−− +−−

mfzfzfzFz mm

2

( )mkf − ( )zFz m−

3

( ) ( ) ( )kfkfkf −+=∆ 1: ( ) ( ) ( )01 fzzFz −−4

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )kfkfkfkf ++−+=∆ 122:2

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )1021

2

fzfzzzFz −−−−5

( )kf3

∆ ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )2130331 23

fzfzzfzzzzFz −−−+−−−6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-271-2048.jpg)

![277

SOLO

Let compute the integrals:

s

R

θ

1C

2C

s

*

s

*

s−

complex

plane

complex

plane

along C1, assuming R → ∞ we have

( )θjRszsz exp

1

*

11

≈

+

≈

−

( ) ( ) ( )∫∫

+

−

−

=

+

+

−

=

CC

dzzF

szszj

dzzF

szszj

sF

*

11

2

1

*

11

2

1

ππ

( ) θθ djRjzd exp=

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) 0exp2

2

1

lim

*

11

2

1

2

2

1

1

∞

−

→∞

=∞==

+

+

−

= ∫∫

atanalyticF

R

C

FdjRFj

j

dzzF

szszj

I

π

π

θθ

ππ

( ) 0

*

11

2

1

1

3 =

+

−

−

= ∫C

dzzF

szszj

I

π

along C2, assuming R → ∞ we have

( )

( )( )

( ) ( )

( )

( )∫∫∫

∞

∞−

=

−=

+=

∞

∞−

−+

−

=

+−

+−

=

+

+

−

=

j

j

vjz

js

js

j

jC

vdvjF

v

vj

zdzF

szsz

ssz

j

dzzF

szszj

I 22

*

2

1

*

*2

2

1

*

11

2

1

2

ωσ

ω

πππ ωσ

ωσ

( )

( )( )

( )

( )

( )∫∫∫

∞

∞−

=

−=

+=

∞

∞−

−+

=

+−

+

=

+

−

−

=

j

j

vjz

js

js

j

jC

vdvjF

v

dzzF

szsz

ss

j

dzzF

szszj

I 22

*

4

1

*

*

2

1

*

11

2

1

2

ωσ

σ

πππ ωσ

ωσ

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

( )∫∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

−+

=

−+

−

=

j

j

j

j

vdvjF

v

vdvjF

v

vj

sF 2222

11

ωσ

σ

πωσ

ω

π

Hilbert Transform](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-277-2048.jpg)

![278

SOLO

Let write

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( )∫∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

−+

=∞+

−+

−

=

j

j

j

j

vdvjF

v

FvdvjF

v

vj

sF 2222

11

ωσ

σ

πωσ

ω

π

( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]ωσωσωσ jFjjFjF +++=+ ImRe

( ){ } ( )[ ] ( )

( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ]( )

( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ]( )∫

∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

+

−+

=

+

−+

−

=+++

j

j

j

j

vdjFjjF

v

vdjFjjF

v

vj

jFjjF

νν

ωσ

σ

π

νν

ωσ

ω

π

ωσωσ

ImRe

1

ImRe

1

ImRe

22

22

We obtain

By equaling the real and imaginary parts we obtain

( )[ ] ( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )

( )[ ]∫∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

−+

=

−+

−

=+

j

j

j

j

vdvjF

v

vdvjF

v

v

jF Re

1

Im

1

Re 2222

ωσ

σ

πωσ

ω

π

ωσ

( )[ ] ( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )

( )[ ]∫∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

−+

=

−+

−

=+

j

j

j

j

vdvjF

v

vdvjF

v

v

jF Im

1

Re

1

Im 2222

ωσ

σ

πωσ

ω

π

ωσ

From those relation we can see that if F (s) is analytic in the right half plane,

then it is enough to know it’s value on the imaginary axis to compute F (s) in

the entire right half plane.

Hilbert Transform](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-278-2048.jpg)

![279

SOLO

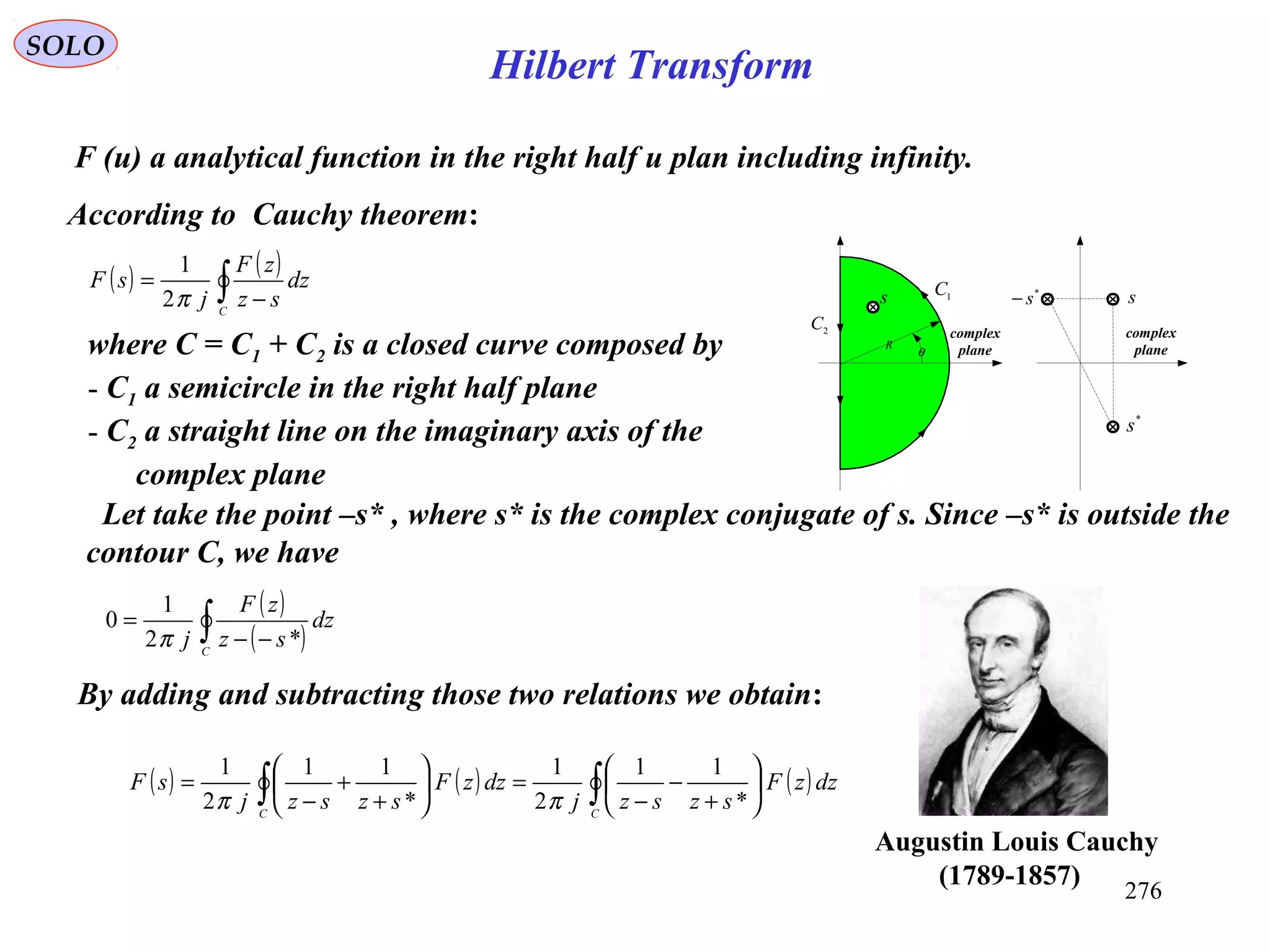

We are interested in cases when σ = 0, i.e. points on the imaginary axis. In this

case:

( )[ ] ( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )

( )[ ]∫∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

−+

=

−+

−

=+

j

j

j

j

vdvjF

v

vdvjF

v

v

jF Re

1

Im

1

Re 2222

ωσ

σ

πωσ

ω

π

ωσ

( )[ ] ( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )

( )[ ]∫∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

−+

=

−+

−

=+

j

j

j

j

vdvjF

v

vdvjF

v

v

jF Im

1

Re

1

Im 2222

ωσ

σ

πωσ

ω

π

ωσ

It seams that we have a singular point ν = ω, on the path of integration, but we

will see how this can be taken care.

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )∫

∞

∞−

−

=

j

j

vd

v

vjF

jF

ωπ

ω

Im1

Re

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )∫

∞

∞−

−

=

j

j

vd

v

vjF

jF

ωπ

ω

Re1

Im

Hilbert Transform](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-279-2048.jpg)

![281

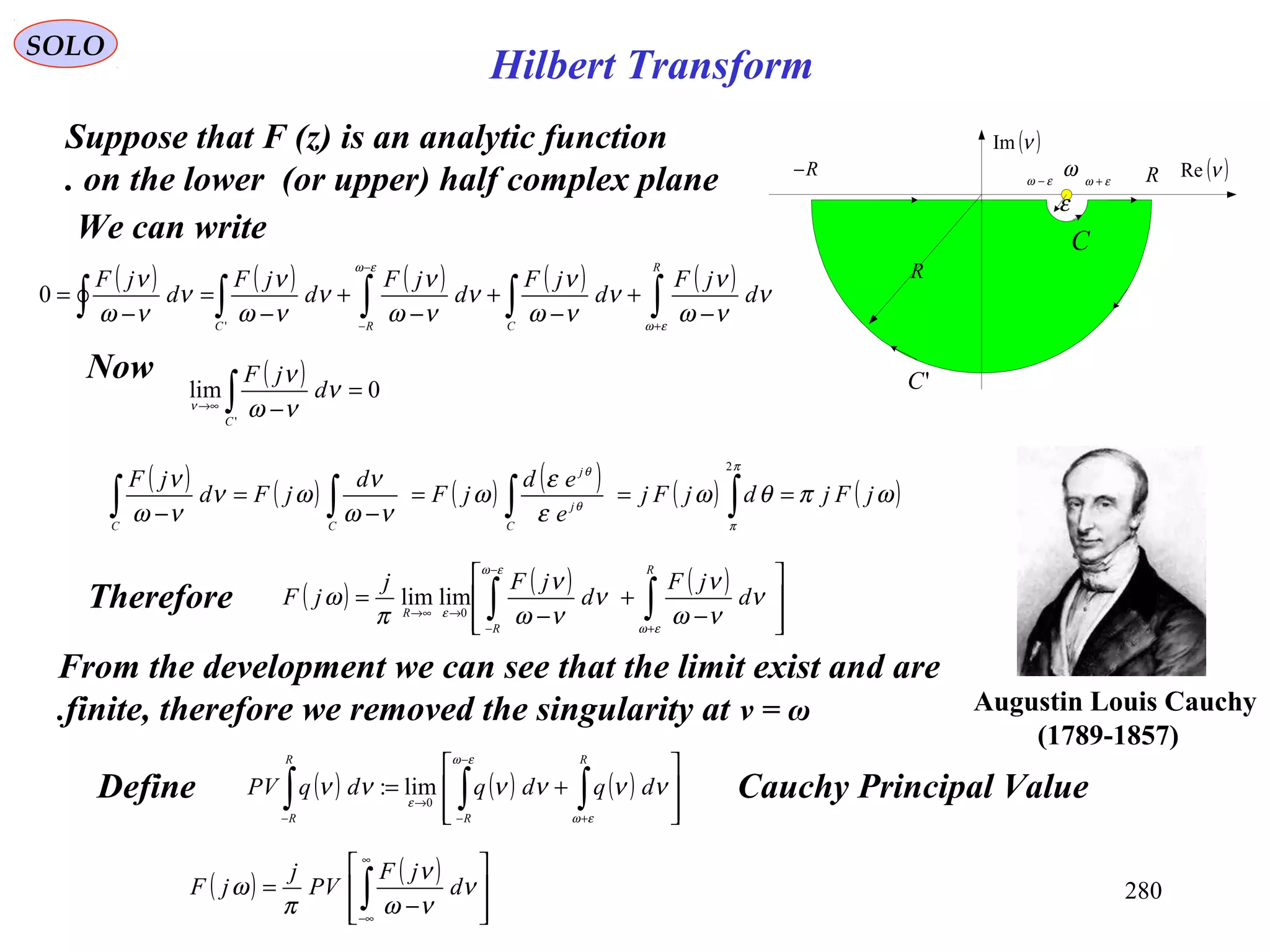

SOLO

Suppose that F (z) is an analytic function

on the lower (or upper) half complex plane.

We can write

( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

−

+

−

−=+= ∫∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

ν

νωπ

ν

νωπ

ωωω d

vjF

PV

j

d

vjF

PVjFjjFjF

ReIm1

ImRe

Comparing real and imaginary parts we obtain

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ]{ }

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ]{ }ων

νωπ

ω

ων

νωπ

ω

jFd

vjF

PVjF

jFd

vjF

PVjF

Re

Re1

Im

Im

Im1

Re

H

H

=

−

=

−=

−

−=

∫

∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

Where H stands for Hilbert Transform.

( ) ( )

−

= ∫

∞

∞−

ν

νω

ν

π

ω d

jF

PV

j

jF

( )νRe

( )νIm

ω εω +εω −

R

RR−

'C

C

ε

David Hilbert

1862 - 1943

Return to Table of Contents

Hilbert Transform](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-281-2048.jpg)

![282

SOLO

References

[2] Churchill, R.V., “Complex Variables and Applications”, McGraw-Hill, Kõgakusha’

1960

[3] Spiegel, M.R., “Complex Variables with an introduction to Conformal Mapping

and its applications”, Schaum’s Outline Series, McGraw-Hill, 1964

[4] Hauser, A.A., “Complex Variables with Physical Applications”, Simon & Schuster,

1971

[5] Fisher, S.D., “Complex Variables”, Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole Mathematics Series,

1986

Complex Variables

[6] Tristan, N., “Visual Complex Analysis”, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1997

[1] E.C. Titchmarsh, “The Theory of Functions”, Oxford University Press, 2nd

Ed., 1939

http://www.ima.umn.edu/~arnold/complex.html](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexvariables-140921180830-phpapp02/75/Mathematics-and-History-of-Complex-Variables-282-2048.jpg)