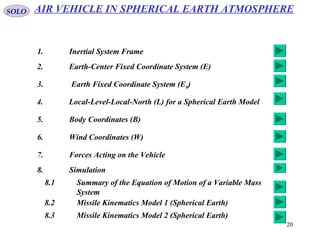

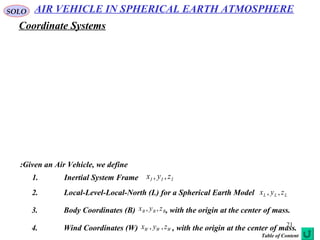

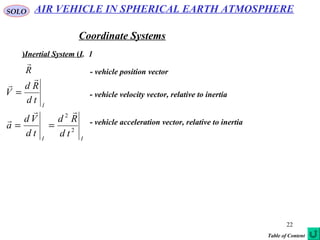

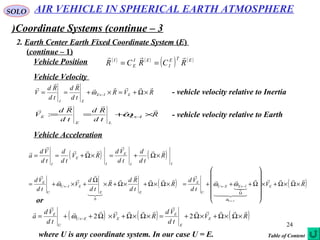

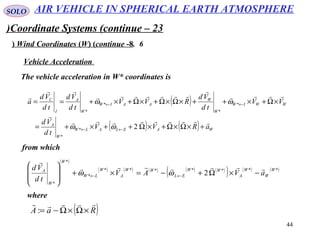

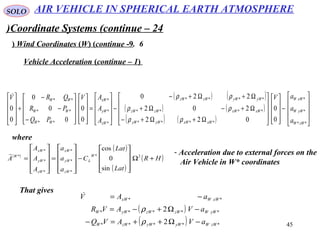

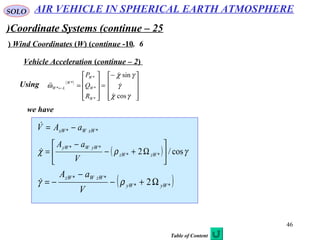

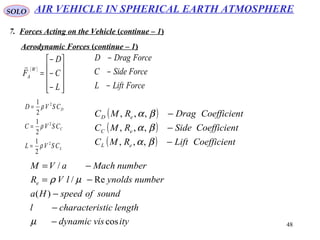

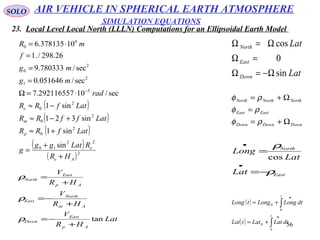

The document outlines the principles of navigation systems for aircraft, detailing the various headings, tracks, and the calculation of deviations from desired flight paths using spherical trigonometry. It also explains the concept of great circles as the shortest distance between two points on Earth and introduces multiple coordinate systems relevant to navigation. Furthermore, it discusses the dynamics of air vehicles within a spherical Earth model and the forces acting on them.

![8

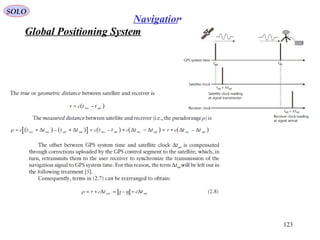

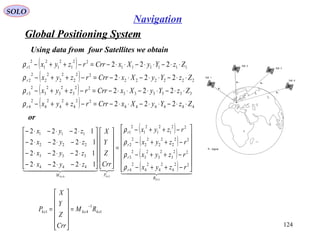

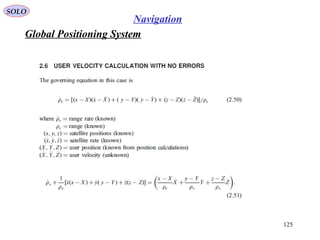

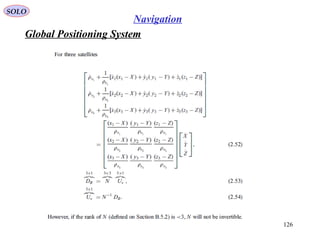

NavigationSOLO

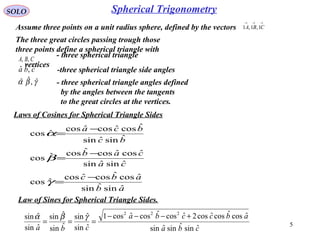

Flight on Earth Great Circles

1

2

111 ,, λφR

222 ,, λφR

The Great Circle Distance between two points 1 and

2 is ρ.

θρ ⋅= a

R – radius

- Latitudeϕ

λ - Longitude

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )212121 cos90sin90sin90cos90cos

/coscos

λλφφφφ

ρθ

−⋅−⋅−+−⋅−=

=

a

From the Law of Cosines for Spherical Triangles

or

( ) ( )212121 coscoscossinsin/cos λλφφφφρ −⋅⋅+⋅=a

( ){ }212121

1

coscoscossinsincos λλφφφφρ −⋅⋅+⋅⋅= −

a

The Initial Heading Angle ψ0 can be obtained using the

Law of Cosines for Spherical Triangles as follows

( )

( )a

a

/sincos

/cossinsin

cos

1

12

0

ρφ

ρφφ

ψ

⋅

⋅−

=

( )[ ]

( )[ ]2

222

22221

coscoscossinsin1cos

coscoscossinsinsinsin

cos

λλφφφφφ

λλφφφφφφ

ψ

−⋅⋅+⋅−⋅

−⋅⋅+⋅⋅−

= −

The Heading Angle ψ from the Present Position (R, ,λ) to Destination Point (Rϕ 2,ϕ2,λ2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-8-320.jpg)

![10

NavigationSOLO

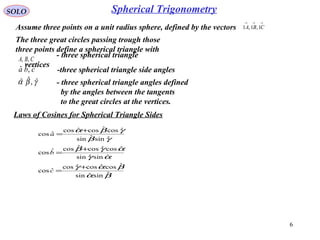

Flight on Earth Great Circles

1

2

111 ,, λφR

222 ,, λφR

If the Aircraft flies with an Heading Error Δψ we want to calculate the Down Range

Error Xd and Cross Range Error Yd, in the Spherical Triangle APB.

R – radius

- Latitudeϕ

λ - Longitude

Using the Law of Cosines for Spherical Triangle APB we have

( ) ( )aaYd /sin

90sin

/sin

sin

ρ

ψ

=

∆

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) 2/sin/sin

/cos/cos/cos

0ˆcos 21

90ˆ

RR

a

aYaX

aYaXa

P

dd

dd

P +

=

⋅

⋅−

==

= ρ

Using the Law of Sines for Spherical Triangle APB we have

( )

( )

⋅= −

aY

a

aX

d

d

/cos

/cos

cos 1 ρ

( )[ ]ψρ ∆⋅⋅= −

sin/sinsin 1

aaYd](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-10-320.jpg)

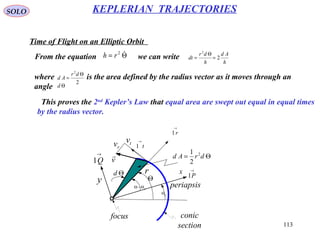

![19

SOLO

4. The Perifocal Coordinate System (Continue)

COORDINATES IN THE SOLAR SYSTEM

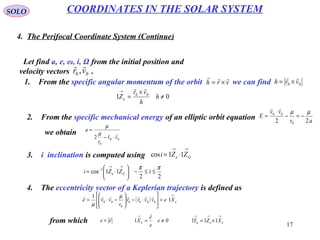

Let find a, e, ω, i, Ω from the initial position and

velocity vectors (continue).00 ,vr

The rotation matrix from the Perifocal Coordinate System Xε , Yε, Zε to the

Geocentric-Equatorial Coordinate System XG, YG, ZG is given by:

[ ] [ ] [ ]

ΩΩ−

ΩΩ

−

−=Ω=

100

0cossin

0sincos

cossin0

sincos0

001

100

0cossin

0sincos

313

ii

iiiCG

ωω

ωω

ωε

Ω−Ω

Ω+Ω−Ω−Ω−

Ω+ΩΩ−Ω

=

iii

iii

iii

cossincossinsin

sincoscoscoscossinsinsincoscoscossin

sinsincoscossinsincossincossincoscos

ωωωωω

ωωωωω](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-19-320.jpg)

![23

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 2)

2. Earth Center Earth Fixed Coordinate –ECEF-System (E(

xE, yE in the equatorial plan with xE pointed to the intersection between the equator

to zero longitude meridian.

The Earth rotates relative to Inertial system I, with the angular velocity

sec/10.292116557.7 5

rad−

=Ω

EIIE zz

11 Ω=Ω=Ω=←ω

( )

Ω

=← 0

0

EC

IEω

Rotation Matrix from I to E

[ ]

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

ΩΩ−

ΩΩ

=Ω=

100

0cossin

0sincos

3 tt

tt

tCE

I

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-23-320.jpg)

![25

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 4)

3.Earth Fixed Coordinate System (E0(

The origin of the system is fixed on the earth at some

given point on the Earth surface (topocentric) of

Longitude Long0 and latitude Lat0.

xE0 is pointed to the geodesic North, yE0 is pointed to the East parallel to Earth

surface, zE0 is pointed down.

[ ] [ ]

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) =

−

−−

−

=−−=

100

0cossin

0sincos

sin0cos

010

cos0sin

2/ 00

00

00

00

3020

0

LongLong

LongLong

LatLat

LatLat

LongLatCE

E π

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

−−−

−

−−

=

00000

00

00000

sinsincoscoscos

0cossin

cossinsincossin

LatLongLatLongLat

LongLong

LatLongLatLongLat

The Angular Velocity of E relative to I is: EIIEIE zz

110 Ω=Ω== ←← ωω or

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( )

Ω−

Ω

=

Ω

−−−

−

−−

=

Ω

=←

0

0

00000

00

00000

00

0

sin

0

cos

0

0

sinsincoscoscos

0cossin

cossinsincossin

0

0

Lat

Lat

LatLongLatLongLat

LongLong

LatLongLatLongLat

CE

E

E

IEω

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE

Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-25-320.jpg)

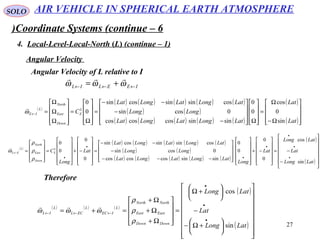

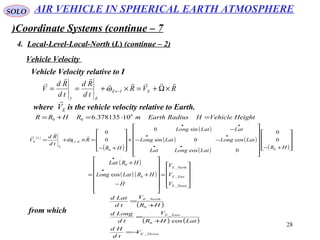

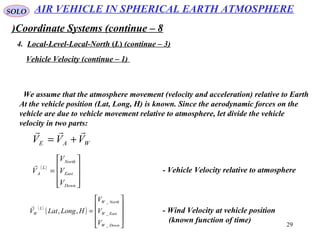

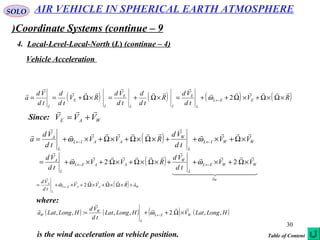

![26

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 5)

4. Local-Level-Local-North (L) or Navigation Frame

The origin of the LLLN coordinate system is located at

the projection of the center of gravity CG of the vehicle

on the Earth surface, with zDown axis pointed down,

xNorth, yEast plan parallel to the local level, with

xNorth pointed to the local North and yEast pointed to

the local East. The vehicle is located at:.

Latitude = Lat, Longitude = Long, Height = H

Rotation Matrix from E to L

[ ] [ ]

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) =

−

−−

−

=−−=

100

0cossin

0sincos

sin0cos

010

cos0sin

2/ 32 LongLong

LongLong

LatLat

LatLat

LongLatCL

E π

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

−−−

−

−−

=

LatLongLatLongLat

LongLong

LatLongLatLongLat

sinsincoscoscos

0cossin

cossinsincossin

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-26-320.jpg)

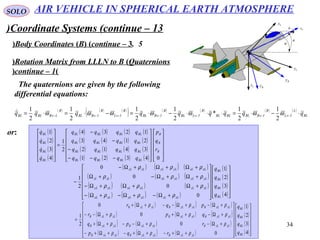

![31

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 10)

5.Body Coordinates (B(

The origin of the Body coordinate system

is located at the instantaneous center of

gravity CG of the vehicle, with xB pointed

to the front of the Air Vehicle, yB pointed

toward the right wing and zB completing

the right-handed Cartesian reference frame.

Rotation Matrix from LLLN to B (Euler Angles(:

[ ] [ ] [ ]

−+

+−

−

==

θφψφψθφψφψθφ

θφψφψθφψφψθφ

θψθψθ

ψθφ

cccssscsscsc

csccssssccss

ssccc

CB

L 321

ψ - azimuth angle

θ - pitch angle

φ - roll angle

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-31-320.jpg)

![32

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 11)

5.Body Coordinates (B( (continue – 1( ψ

θ

φ Bx

Lx

Bz

Ly

Lz

By

Angular Velocity from L to B (Euler Angles(:

( )

[ ] [ ] [ ]

+

+

=

=←

ψ

θφθφ

φ

ω

0

0

0

0

0

0 211

R

Q

P

B

LB

−

−

+

−

+

=

ψθθ

θθ

φφ

φφθ

φφ

φφ

φ

0

0

cos0sin

010

sin0cos

cossin0

sincos0

001

0

0

cossin0

sincos0

001

0

0

[ ]

=

−

−

=

ψ

θ

φ

ψ

θ

φ

θφφ

θφφ

θ

G

coscossin0

cossincos0

sin01

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-32-320.jpg)

![33

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 12)

5.Body Coordinates (B( (continue – 2( ψ

θ

φ Bx

Lx

Bz

Ly

Lz

By

Rotation Matrix from LLLN to B (Quaternions(:

( ) [ ][ ] ( ) [ ][ ] { } { }

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

−−−

−

−

−

−−

−−

−−

=

+×−×−=

321

412

143

234

3412

2143

1234

44 3333

BIBLBL

BLBLBL

BLBLBL

BLBLBL

BLBLBLBL

BLBLBIBL

BLBLBLBL

T

BLBLBLXBLBLXBL

B

L

qqq

qqq

qqq

qqq

qqqq

qqqq

qqqq

qqqIqqIqC

where: ( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

{ }

( )

{ }

( )

( )

( )

=

=

=

=

3

2

1

:&

4

4

3

2

1

4

3

2

1

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

BL

q

q

q

q

q

q

qor

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

( )

−

=

2

sin

2

sin

2

sin

2

cos

2

cos

2

cos4

ϕθψϕθψ

BLq

( )

+

=

2

cos

2

sin

2

sin

2

sin

2

cos

2

cos1

ϕθψϕθψ

BLq

( )

−

=

2

sin

2

cos

2

sin

2

cos

2

sin

2

cos2

ϕθψϕθψ

BLq

( )

+

=

2

sin

2

sin

2

cos

2

cos

2

cos

2

sin3

ϕθψϕθψ

BLq

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-33-320.jpg)

![36

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 15)

6.Wind Coordinates (W(

The origin of the Wind coordinate system

is located at the instantaneous center of

gravity CG of the vehicle, with xW pointed

in the direction of the vehicle velocity vector

relative to air .AV

[ ] [ ]

−

−−=

−

−=−=

αα

βαββα

βαββα

αα

αα

ββ

ββ

αβ

cos0sin

sinsincossincos

cossinsincoscos

cos0sin

010

sin0cos

100

0cossin

0sincos

23

W

BC

The Wind coordinate frame is defined by the following two angles:

α - angle of attack

β - sideslip angle

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-36-320.jpg)

![37

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 16)

6.Wind Coordinates (W( (continue -1(

Rotation Matrix from L (LLLN) to W is:

χ - azimuth angle of the trajectory

γ - pitch angle of the trajectory

Rotation Matrix

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] 32123 ψθφαβ −== B

L

W

B

W

L CCC

The Rotation Matrix from L (LLLN) to W can also be defined by the following

Consecutive rotations:

σ - bank angle of the

trajectory

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]

−+

+−

−

===

γσχσχγσχσχγσ

γσχσχγσχσχγσ

γχγχγ

χγσσ

cccssscsscsc

csccssssccss

ssccc

CC W

L

W

L 321

*

1

We defined also the intermediate wind frame W* by:

[ ] [ ]

−

−

==

γχγχγ

χχ

γχγχγ

χγ

csscs

cs

ssccc

CW

L 032

*

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-37-320.jpg)

![38

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 17)

6.Wind Coordinates (W( (continue -2(

Angular Velocity of W* relative to LLLN is:

Angular Velocities

( )

[ ]

−

=

−

+

=

+

=

=←

γχ

γ

γχ

χγγ

γγ

γ

χ

γγω

cos

sin

0

0

cos0sin

010

sin0cos

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

*

*

*

*

*

W

W

W

W

LW

R

Q

P

Angular Velocity of W relative to LLLN is:

( )

[ ] [ ]

−

−

=

−

−

+

=

+

+

=

=←

χ

γ

σ

γσσ

γσσ

γ

γχ

γ

γχ

σσ

σσ

σ

χ

γγσ

σ

ω

coscossin0

cossincos0

sin01

cos

sin

cossin0

sincos0

001

0

00

0

0

0

0

0 21

W

W

W

W

LW

R

Q

P

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-38-320.jpg)

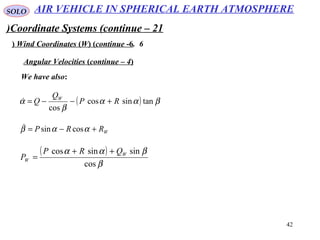

![39

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 18)

6.Wind Coordinates (W( (continue -3(

We have also:

Angular Velocities (continue – 1(

( ) ( )

( )

( )

Ω

Ω

Ω

=

Ω−

Ω

==

Ω

Ω

Ω

= ←←

Down

East

North

W

L

W

L

L

IE

W

L

zW

yW

xW

W

IE C

Lat

Lat

CC ***

*

*

*

*

sin

0

cos

ωω

( ) ( )

( )

( )

=

−

−==

=

•

•

•

←←

Down

East

North

W

L

W

L

L

EL

W

L

zW

yW

xW

W

EL C

LatLong

Lat

LatLong

CC

ρ

ρ

ρ

ω

ρ

ρ

ρ

ω ***

*

*

*

*

sin

cos

( ) ( )

( )

( )

[ ] ( )*

1

sin

0

cos

W

IE

W

L

L

IE

W

L

zW

yW

xW

W

IE

Lat

Lat

CC ←←← =

Ω−

Ω

==

Ω

Ω

Ω

= ωσωω

( ) ( )

( )

( )

[ ] ( )*

1

sin

cos

W

IL

W

L

L

IL

W

L

W

IL

LatLong

Lat

LatLong

CC ←

•

•

•

←← =

+Ω−

−

+Ω

== ωσωω

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-39-320.jpg)

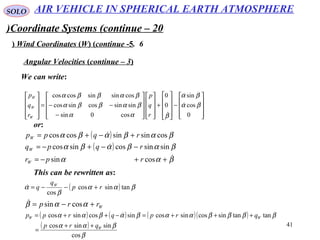

![40

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 19)

6.Wind Coordinates (W( (continue -4(

The Angular Velocity from I to W is:

Angular Velocities (continue – 2(

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

Ω+

Ω+

Ω+

+

=+

=+=

= ←←←←

DownDown

EastEast

NorthNorth

W

L

W

W

W

L

IL

W

L

W

W

W

W

IL

W

LW

W

W

W

W

IW C

R

Q

P

C

R

Q

P

r

q

p

ρ

ρ

ρ

ωωωω

Using the angle of attack α and the sideslip angle β , we can write:

BWBW yz

11 αβω −=←

or:

( ) ( ) ( )

[ ]

−

=

−

=−= ←←←

0

0

0

0

3 αβ

β

ωωω

r

q

p

C

r

q

p

W

B

W

W

W

W

IB

W

IW

W

BW

but also:

( ) ( ) ( )

[ ]

−

=

−

=−= ←←←

0

0

0

0

3 αβ

β

ωωω

R

Q

P

C

R

Q

P

W

B

W

W

W

W

LB

W

LW

W

BW

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-40-320.jpg)

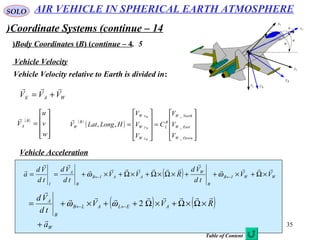

![43

SOLO

Coordinate Systems (continue – 22)

6.Wind Coordinates (W( (continue -7(

The vehicle velocity was decomposed in:

Vehicle Velocity

WAE VVV

+=

( )

=

0

0

V

V

W

A

- vehicle velocity relative to atmosphere

( )

( )

=

=

DownW

EastW

NorthW

W

L

zW

yW

xW

W

W

V

V

V

C

V

V

V

HLongLatV

W

W

W

_

_

_

,,

- wind velocity at velocity position

also

( )

[ ] ( )

[ ]

=

−=−=

0

0

0

011

*

VV

VV

W

A

W

A σσ

( )

( )

=

=

DownW

EastW

NorthW

W

L

zW

yW

xW

W

W

V

V

V

C

V

V

V

HLongLatV

W

W

W

_

_

_

*

*

*

*

*

,,

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-43-320.jpg)

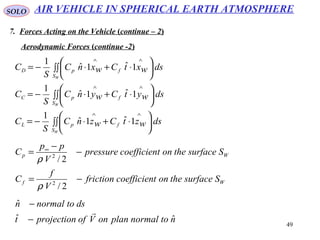

![47

SOLO

Aerodynamic Forces

( )[ ]∫∫ +−= ∞

WS

A dstfnppF

11

ntonormalplanonVofprojectiont

dstonormaln

ˆˆ

ˆ

−

−

( )

airflowingthebyweatedsurfaceVehicleS

SsurfacetheonmNstressforcefrictionf

Ssurfacetheondifferencepressurepp

W

W

W

−

−

−−∞

)/( 2

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE

7. Forces Acting on the Vehicle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-47-320.jpg)

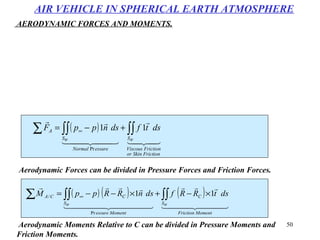

![51

SOLO

( ) ( ) ( )∫∫ −++= ∞

<> iopenS

outflowoutopenflowinflowinopenflow dsnppmVmVT

1:

0

/

0

/ THRUST FORCES

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]∫∫ −×−+×−−×−= ∞

<> iopenS

OoutflowoutopenflowCoutopeninflowinopenflowCiopenCT dsnppRRmVRRmVRRM

1:

0

/

0

/,

THRUST MOMENTS

RELATIVE TO C

( ) ( )∫∫ −+ ∞

> inopenS

inflowinopenflow dsnppmV

1

00

/

( ) ( )∫∫ −+ ∞

< outopenS

outflowoutopenflow dsnppmV

1

0

/

T

outopenR

iopenR

CR

C

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE

Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-51-320.jpg)

![52

SOLO

7. Forces Acting on the Vehicle (continue – 3)

Thrust

( ) ( )

−

−−==

B

B

B

z

y

x

BW

B

W

T

T

T

TCT

αα

βαββα

βαββα

cos0sin

sinsincossincos

cossinsincoscos

**

( )

[ ] ( )

−

==

=

*

*

*

cossin0

sincos0

001

*

1

W

W

W

W

W

W

z

y

x

W

z

y

x

W

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

σσ

σσσ

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE

F-35Thrust Vector Control](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-52-320.jpg)

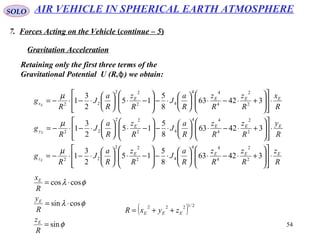

![53

SOLO

7. Forces Acting on the Vehicle (continue – 4)

Gravitation Acceleration

( ) ( )

−

−

−

==

zg

yg

xg

gg

100

0

0

0

010

0

0

0

001

χχ

χχ

γγ

γγ

σσ

σσ cs

sc

cs

sc

cs

scC EW

E

W

( )

gg

−

=

γσ

γσ

γ

cc

cs

s

W

2sec/174.322sec/81.9

0

2

0

0

0

gg ftmg

HR

R

==

+

=

AIR VEHICLE IN SPHERICAL EARTH ATMOSPHERE

The derivation of Gravitation Acceleration assumes an Ellipsoidal Symmetrical Earth.

The Gravitational Potential U (R, ( is given byϕ

( ) ( )

( )

( )φ

φ

µ

φ

,

sin1, 2

RUg

P

R

a

J

R

RU

E

E

n n

n

n

∇=

−⋅−= ∑

∞

=

μ – The Earth Gravitational Constant

a – Mean Equatorial Radius of the Earth

R=[xE

2

+yE

2

+zE

2

]]/2

is the magnitude of

the Geocentric Position Vector

– Geocentric Latitude (sin =zϕ ϕ E/R(

Jn – Coefficients of Zonal Harmonics of the

Earth Potential Function

P (sin ( – Associated Legendre Polynomialsϕ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-53-320.jpg)

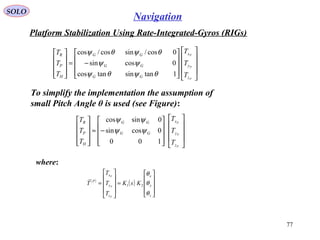

![SOLO

75

Navigation

Platform Stabilization Using Rate-Integrated-Gyros (RIGs(

The Platform is angular isolated from the Aircraft

via, at least, three Gimbals. Those Gimbals are,

from Aircraft to Platform:

- Azimuth (Heading( – Angle ψG

- Pitch – Angle θ

- Roll – Angle ϕ

The Rotation Matrix from Aircraft to Platform is:

[ ] [ ] [ ]

−

−

−

==

100

0cossin

0sincos

cos0sin

010

sin0cos

cossin0

sincos0

001

321 GG

GG

G

P

AC ψψ

ψψ

θθ

θθ

φφ

φφψθφ

We want to apply Moments on the Platform, related to the Pjckoff

Outputs

of the Three RIGs mounted on the Platform

( )

( )

=

=

z

y

x

z

y

x

P

KsK

T

T

T

T

P

P

P

θ

θ

θ

21

The 3 Torque Motors Roll (TR(, Pitch (TP( and Heading (TH(

are located on Gimbal Axes .PA zyx 1,1,1 '

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-75-320.jpg)

![SOLO

76

Navigation

Platform Stabilization Using Rate-Integrated-Gyros (RIGs(

We want to find the relation between and

TR, TP, TH.

PPP zyx TTT ,,

The 3 Torque Motors Roll (TR(, Pitch (TP( and Heading (TH(

are located on Gimbal Axes .PA zyx 1,1,1 '

PAPPPPPP zHyPxRzzyyxx TTTTTTT 111111 '

++=++=

( )

[ ] [ ] [ ]

( )

[ ] [ ]

( )

[ ]

( )

P

Pzy

A

Ax

P

P

P

GHGPGR

z

y

x

P

TTT

T

T

T

T

1

3

1

23

1

123

1

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

,

'

−+

−−+

−−−=

= ψθψφθψ

−

−

=

H

P

R

GG

GG

z

y

x

T

T

T

T

T

T

P

P

P

10sin

0coscossin

0sincoscos

θ

ψθψ

ψθψ

−=

P

P

P

z

y

x

GG

GG

GG

H

P

R

T

T

T

T

T

T

1tansintancos

0cossin

0cos/sincos/cos

θψθψ

ψψ

θψθψ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-76-320.jpg)

![SOLO

79

Navigation

Derivation of the IMU Position and Platform Misalignment Error Equations

Platform Misalignment Error Equations

Define:

(C(Computer Coordinate System

(the computed Platform coordinates(

(P( Platform Coordinate System

(real Platform coordinates(

The rotation from (C( to (P( is defined by

the three small angles ψx, ψy, ψz as

[ ] [ ] [ ]

−

−

−

==

100

0cossin

0sincos

cos0sin

010

sin0cos

cossin0

sincos0

001

321 zz

zz

yy

yy

xx

xxzyx

P

CC ψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψψψψψ

−

−

−

−

=

−

−

−

≈

−

−

−

≈

0

0

0

100

010

001

1

1

1

100

01

01

10

010

01

10

10

001

xy

xz

yz

xy

xz

yz

z

z

y

y

x

x

ψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψ

ψ

ψ

ψ

ψ

ψ

[ ] [ ] [ ]

−

−

−

=×

=×−≈

0

0

0

:&:

xy

xz

yz

z

y

x

P

C IC

ψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψ

ψ

ψ

ψ

ψψ

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-79-320.jpg)

![SOLO

80

Navigation

Derivation of the IMU Position and Platform Misalignment Error Equations

Platform Misalignment Error Equations (continue – 1(

Let find the angular rotation vector from C to P

( )

[ ] [ ] [ ] =

+

+

=←

z

zyy

x

x

P

CP

ψ

ψψψ

ψ

ψω

0

0

0

0

0

0 321

ψ

ψ

ψ

ψ

ψ

ψψψ

ψψψ

ψψψ

ψψ

ψψ

ψ

ψ

ψψ

=

≈

+

−

=

−

−

−

+

−

+

≈

z

y

x

z

zxy

zyx

zxy

xz

yz

y

y

yx

0

0

1

1

1

0

0

10

010

01

0

0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-80-320.jpg)

![SOLO

82

Navigation

Derivation of the IMU Position and Platform Misalignment Error Equations

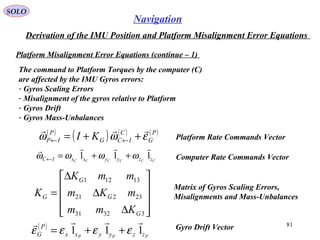

Platform Misalignment Error Equations (continue – 2(

Let find the angular velocity vector of the Platform (P(

relative to the Computer (C(:

ICIPCP ←←← −= ωωω

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )C

IC

P

C

P

IP

P

IC

P

IP

P

CP C ←←←←← −=−= ωωωωω

( ) ( ) ( )

[ ]{ } ( )

[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )P

G

C

ICG

C

IC

C

IC

P

G

C

ICG KIKI εωωψωψεωψ

++×=×−−++= ←←←←

Using we obtain:[ ] ( ) ( )

[ ] ψωωψ

×−=× ←←

C

IC

C

IC

( )

[ ] ( ) ( )P

G

C

ICG

C

IC K εωψωψ

++×−= ←←

or

+

∆

∆

∆

+

−

−

−

−=

z

y

x

z

y

x

G

G

G

z

y

x

xy

xz

yz

z

y

x

C

C

C

CC

CC

CC

Kmm

mKm

mmK

ε

ε

ε

ω

ω

ω

ψ

ψ

ψ

ωω

ωω

ωω

ψ

ψ

ψ

33231

23221

13121

0

0

0

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-82-320.jpg)

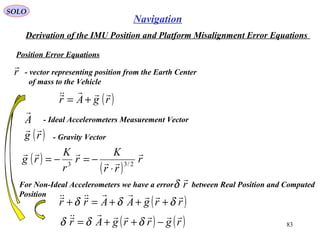

![SOLO

84

Navigation

Derivation of the IMU Position and Platform Misalignment Error Equations

Position Error Equations (continue – 1(

( ) ( )rgrrgAr

−++= δδδ

( ) ( )

( ) ( )[ ]

r

r

K

r

rrrr

K

rgrrg

32/3

+

+⋅+

−=−+

δδ

δ

( )

( ) r

r

K

r

rr

rr

r

K

r

r

K

r

rrr

K

32332/32

31

2

+

⋅

−+−≈+

⋅+

−≈

δ

δ

δ

r

r

K

r

r

r

r

r

r

K

r

r

K

r

r

K

3333

+

⋅+−−≈ δδ

therefore

Ar

r

r

r

r

r

r

K

r

δδδδ =

⋅−+ 33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-84-320.jpg)

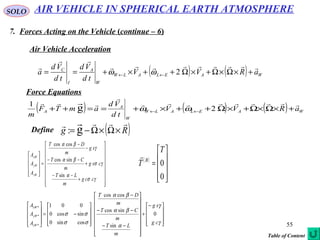

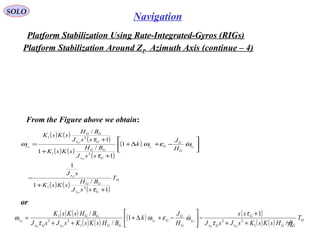

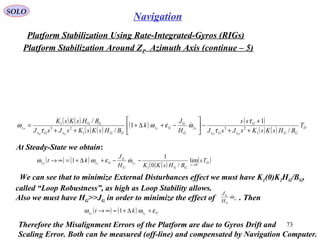

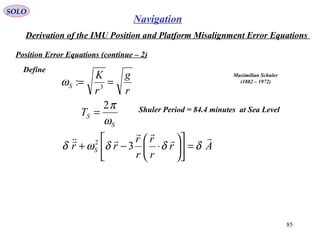

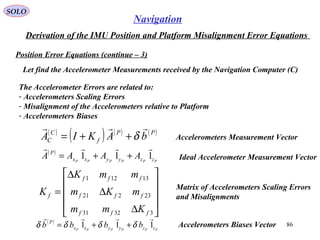

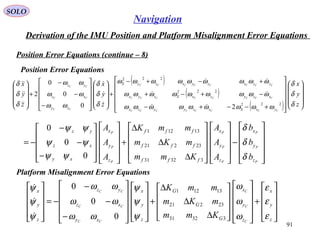

( )PPP

f

PC

P

C

C

C

AIbAKIACAA

×+−++=−= ψδδ

We used the relation ( ) [ ]( ) [ ]( )×+≈×−==

−−

ψψ

IICC P

C

C

P

11

Finally we obtain

( )

[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )PP

f

PC

bAKAA

δψδ ++×−=

[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )PP

f

P

S bAKAr

r

r

r

r

rr

δψδδωδ ++×−=

⋅−+ 32

The Position Error Equation is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-87-320.jpg)

![SOLO

88

Navigation

Derivation of the IMU Position and Platform Misalignment Error Equations

Position Error Equations (continue – 5(

Let compute ( )C

r

δ

( ) ( ) ( )

[ ] ( )CC

IC

CC

rrr

δωδδ ×+= ←

Therefore

( )

( )

( )

( ) ( )

CCCCCC

CCC

C

IC

C

CCC

CCC

CCCCCC

CCC

zzyyxxIC

C

ICzyxICzyx

zyx

C

zyxzyx

C

zyx

C

rzyxzyx

zyxr

zyxzyxr

zyxr

111

111111

111:

111111

111

11

ωωωω

δωδδδωδδδ

δδδδ

δδδδδδδ

δδδδ

αα

ω

++=

×=++×=++

++=

+++++=

++=

←

←←

×= ←

In the same way

( ) ( ) ( )

[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )

[ ] ( ) ( )

( )

[ ] ( ) ( )

[ ] ( )

( )CC

IC

CC

IC

CC

IC

C

IC

C

IC

CC

IC

CC

rr

rrrr

δωδω

δωωωδωδδ

×+×+

×

×++×+=

←←

←←←←

0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-88-320.jpg)

![SOLO

89

Navigation

Derivation of the IMU Position and Platform Misalignment Error Equations

Position Error Equations (continue – 6(

( ) ( ) ( )

[ ] ( )CC

IC

CC

rrr

δωδδ ×+= ←

Therefore

( ) ( ) ( )

[ ] ( ) ( )

[ ] ( )

[ ] ( )

[ ]( ) ( )CC

IC

C

IC

C

IC

CC

IC

CC

rrrr

δωωωδωδδ ××+×+×+= ←←←←2

( ) ( )

[ ] ( ) ( )

[ ] ( )

[ ] ( )

[ ]( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( )

[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )PP

f

P

C

CC

C

S

CC

IC

C

IC

C

IC

CC

IC

C

bAKA

r

r

r

r

r

rrrr

δψ

δδωδωωωδωδ

++×−=

⋅−+××+×+×+ ←←←← 32 2

Together with the Platform Misalignment Error Equations

( )

[ ] ( ) ( )P

G

C

ICG

C

IC K εωψωψ

++×−= ←←](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-89-320.jpg)

![SOLO

90

Navigation

Derivation of the IMU Position and Platform Misalignment Error Equations

Position Error Equations (continue – 7(

CCCCCC zzyyxxIC 111

ωωωω ++=←

( )

[ ]

−

−

−

=×←

0

0

0

CC

CC

CC

xy

xz

yz

C

IC

ωω

ωω

ωω

ω

( )

[ ]

−

−

−

=×←

0

0

0

CC

CC

CC

xy

xz

yz

C

IC

ωω

ωω

ωω

ω

( )

[ ] ( )

[ ]

( )

( )

( )

+−

+−

+−

=

−

−

−

−

−

−

=×× ←←

22

22

22

0

0

0

0

0

0

CCCCCC

CCCCCC

CCCCCC

CC

CC

CC

CC

CC

CC

yxzyzx

zyzxyx

zxyxzy

xy

xz

yz

xy

xz

yz

C

IC

C

IC

ωωωωωω

ωωωωωω

ωωωωωω

ωω

ωω

ωω

ωω

ωω

ωω

ωω

Czrr 1

= ( )

( )

( )

( )

−

=

−

=

⋅−

z

y

x

z

z

y

x

r

r

r

r

r

r

C

C

C

C

δ

δ

δ

δ

δ

δ

δ

δδ

21

0

0

33

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-90-320.jpg)

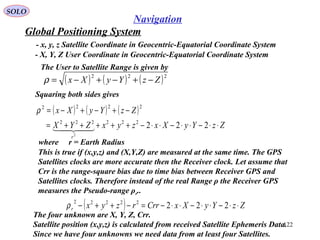

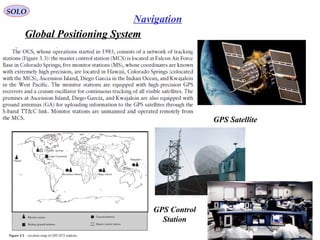

![Global Positioning System

SOLO

110

Navigation

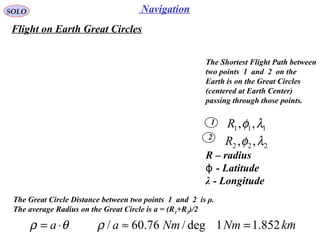

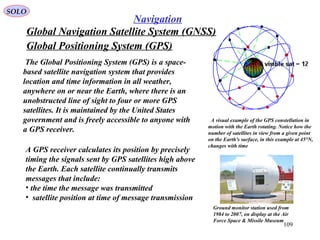

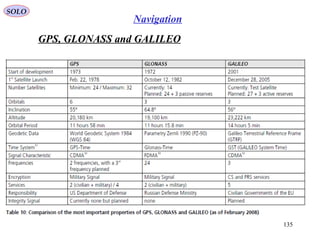

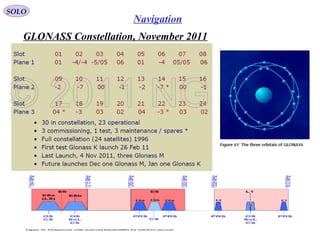

Other satellite navigation systems in use or

various states of development include:

• GLONASS – Russia's global navigation

system. Fully operational worldwide.

• GALILEO – a global system being

developed by the European Union and other

partner countries, planned to be operational

by 2014 (and fully deployed by 2019)

• BEIDOU – People's Republic of China's

regional system, currently limited to Asia and

the West Pacific[123]

• COMPASS – People's Republic of China's

global system, planned to be operational by

2020.

• IRNSS – India's regional navigation

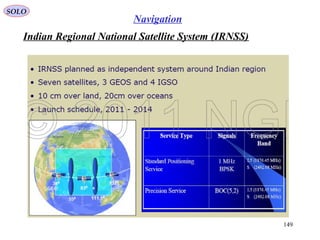

system, planned to be operational by 2012,

covering India and Northern Indian Ocean.

• QZSS – Japanese regional system covering

Asia and Oceania.

Comparison of GPS, GLONASS, Galileo and Compass (medium earth orbit)

satellite navigation system orbits with the International Space Station, Hubble

Space Telescope and Iridium constellation orbits, Geostationary Earth Orbit, and

the nominal size of the Earth.[121]

The Moon's orbit is around 9 times larger (in

radius and length) than geostationary orbit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-110-320.jpg)

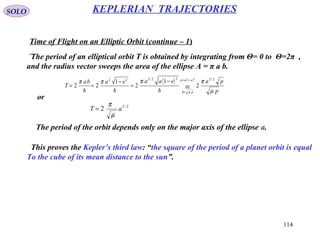

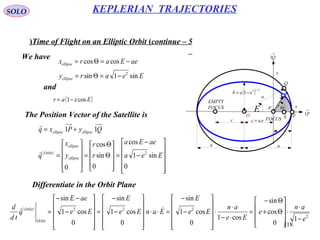

![117

SOLO KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Time of Flight on an Elliptic Orbit (continue – 4)

From

x

y

eac =

a a

( ) 2/12

1 eab −=

rΘ

FOCUS

EMPTY

FOCUS

c

→

P1

→

Q1

a

F

Q

O VS

E

P

Eeary

aeEarx

ellipse

ellipse

sin1sin

coscos

2

−=Θ=

−=Θ=

we have

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]

( )Eea

EeEeaEeaaeEar

cos1

coscos21sin1cos

2/1222/12222

−=

+−=−+−=

Therefore

Θ+

Θ−

=

−

−

=Θ

Θ+

Θ+

=

−

−

=Θ

cos1

sin1

sin

cos1

sin1

sin

cos1

cos

cos

cos1

cos

cos

22

e

e

E

Ee

Ee

e

e

E

Ee

eE

( )( )

Ee

Ee

Ee

eEEe

sin1

cos11

sin1

coscos1

sin

cos1

2

tan

22

−

−+

=

−

+−−

=

Θ

Θ−

=

Θ

From

2

tan

1

1

2

tan

E

e

e

−

+

=

Θ

or

and are always in the same quadrant.2

Θ

2

E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-117-320.jpg)

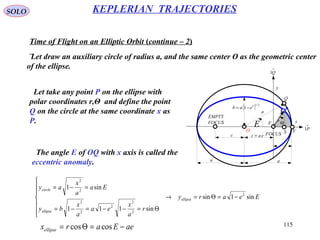

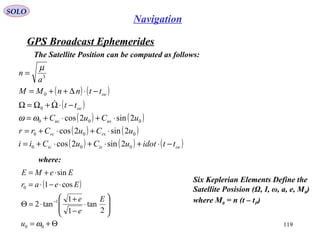

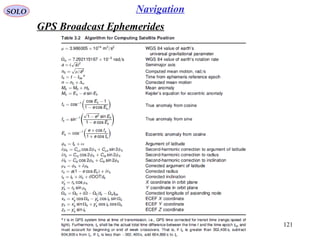

![GPS Broadcast Ephemerides

SOLO

120

Navigation

( )

Θ+=

=

= ωuur

ur

y

x

q ellipse

ellipse

Orbit

0

sin

cos

0

( )

2

1

0

cos

sin

0

e

an

ue

u

y

x

q ellipse

ellipse

Orbit

Orbit

−

⋅

⋅

+

−

=

=

( ) oecoec ttt ⋅+−⋅=Θ ωω

[ ] [ ] [ ]

−−Ω−=

=

0

sin

cos

0

313 ur

ur

iy

x

C

z

y

x

ellipse

ellipse

G

G

ωε

Θ+= ωu](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-120-320.jpg)

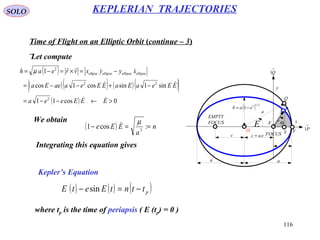

![SOLO

166

Navigation

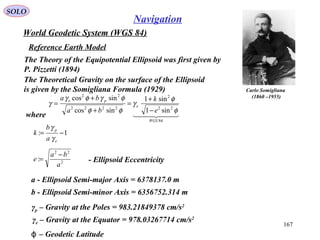

World Geodetic System (WGS 84)

Reference Earth Model

Clairaut's theorem

Clairaut's theorem, published in 1743 by Alexis Claude Clairaut in

his Théorie de la figure de la terre, tirée des principes de

l'hydrostatique,[1]

synthesized physical and geodetic evidence that

the Earth is an oblate rotational ellipsoid. It is a general

mathematical law applying to spheroids of revolution. It was

initially used to relate the gravity at any point on the Earth's

surface to the position of that point, allowing the ellipticity of the

Earth to be calculated from measurements of gravity at different

latitudes.

Clairaut's formula for the acceleration due to gravity g on the surface of a spheroid

at latitude φ, was:

where G is the value of the acceleration of gravity at the equator, m the ratio of

the centrifugal force to gravity at the equator, and f the flattening of a meridian

section of the earth, defined as:

a

ba

f

−

=:

Alexis Claude Clairaut

)1713–1765(

−+= φ2

sin

2

5

1 fmGg](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-166-320.jpg)

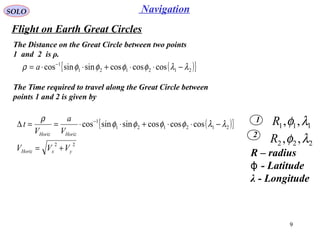

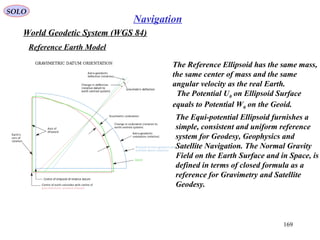

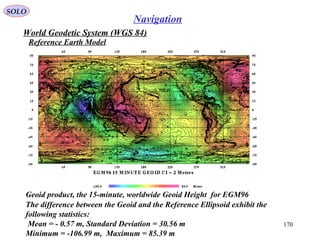

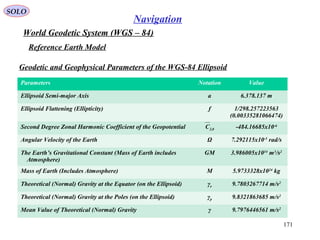

![SOLO

168

Navigation

World Geodetic System (WGS 84)

Reference Earth Model

The coordinate origin of WGS 84 is meant to be located at the

Earth's center of mass; the error is believed to be less than 2 cm.

The WGS 84 meridian of zero longitude is the IERS Reference

Meridian. 5.31 arc seconds or 102.5 meters (336.3 ft) east of the

Greenwich meridian at the latitude of the Royal Observatory.

The WGS 84 datum surface is an oblate spheroid (ellipsoid) with major

(transverse) radius a = 6378137 m at the equator and flattening

f = 1/298.257223563.The polar semi-minor (conjugate) radius b then equals a

times (1−f), or b = 6356752.3142 m.

Presently WGS 84 uses the EGM96 (Earth Gravitational Model 1996) Geoid,

revised in 2004. This Geoid defines the nominal sea level surface by means of a

spherical harmonics series of degree 360 (which provides about 100 km

horizontal resolution).[7]

The deviations of the EGM96 Geoid from the WGS 84

Reference Ellipsoid range from about −105 m to about +85 m.[8]

EGM96 differs

from the original WGS 84 Geoid, referred to as EGM84.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-168-320.jpg)

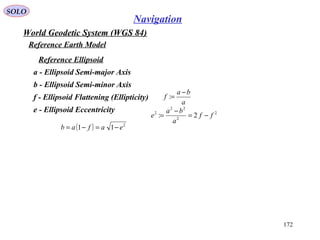

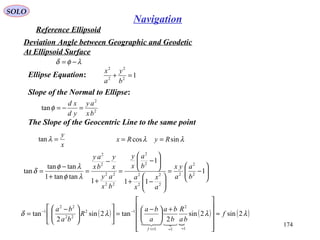

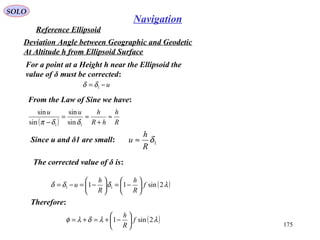

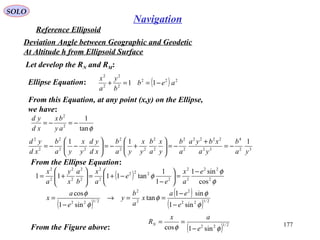

![SOLO

179

Navigation

Reference Ellipsoid

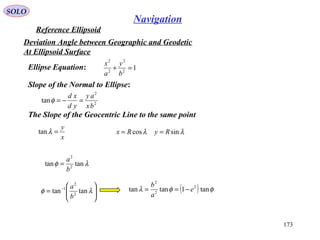

Deviation Angle between Geographic and Geodetic

At Altitude h from Ellipsoid Surface

( )

( ) 2/322

2

sin1

1

:

φe

ea

RM

−

−

=

( ) 2/122

sin1cos φφ e

ax

RN

−

==

a

ba

f

−

=: 2

2

22

2

2: ff

a

ba

e −=

−

=Using

( )

( )[ ]

( ) ( ) [ ] ++−≈

+−++−≈

−−

−

= φφ

φ

2222

2/322

2

sin321sin2

2

3

121

sin21

1

: ffaffffa

ff

fa

RM

( )[ ]

( ) [ ]φφ

φ

222

2/122

sin31sin2

2

3

1

sin21

faffa

ff

a

RN +≈

+−+≈

−−

=

[ ]φ2

sin321 ffaRM +−≈

[ ]φ2

sin31 faRN +≈

We used and we neglect f2

terms

( )

( ) +

−

++=

− !2

1

1

1

1 nn

xn

x

n](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-179-320.jpg)

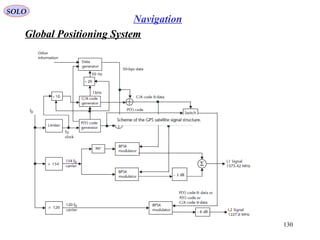

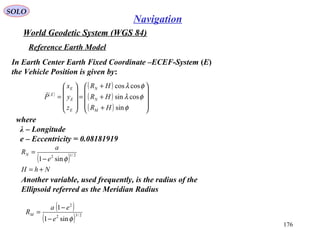

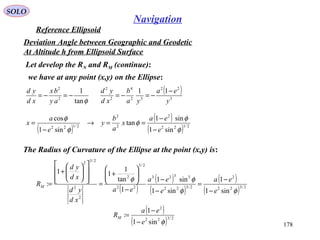

![SOLO

180

Navigation

World Geodetic System (WGS 84)

Reference Earth Model

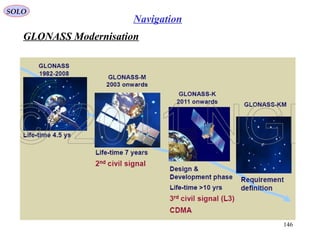

The definition of geodetic latitude (φ) and

longitude (λ) on an ellipsoid. The normal

to the surface does not pass through the

centre

Reference Ellipsoid

Geodetic latitude: the angle between the

normal and the equatorial plane. The

standard notation in English publications is ϕ

Geocentric latitude: the equatorial plane and

the radius from the centre to a point on the

surface. The relation between the geocentric

latitude (ψ) and the geodetic latitude ( ) isϕ

derived in the above references as

The definition of geodetic (or

geographic) and geocentric latitudes

( ) ( )[ ]φφψ tan1tan 21

e−= −](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-navigationsystems-150812122519-lva1-app6892/85/4-navigation-systems-180-320.jpg)