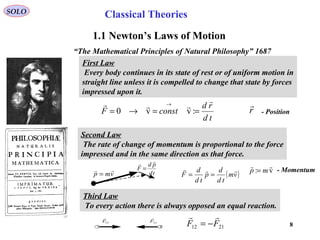

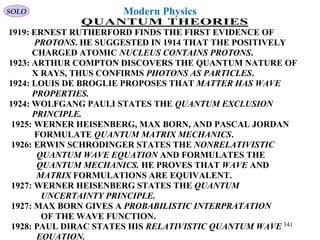

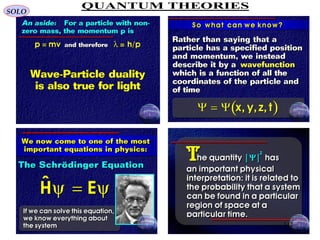

The document is a comprehensive overview of quantum mechanics, spanning its historical development, fundamental principles, and key theories. It discusses significant milestones in the field, including the discovery of the electron, the development of the Schrödinger equation, and interpretations of quantum mechanics like the Copenhagen interpretation. The author expresses a desire to share their findings and invites feedback on their presentation.

![22

MAXWELL’s EQUATIONS

SOLO

Magnetic Field IntensityH

[ ]1−

⋅mA

Electric DisplacementD

[ ]2−

⋅⋅ msA

Electric Field IntensityE

[ ]1−

⋅mV

Magnetic InductionB

[ ]2−

⋅⋅ msV

Electric Current DensityeJ

[ ]2−

⋅mA

Free Electric Charge Distributioneρ [ ]3−

⋅⋅ msA

1. AMPÈRE’S CIRCUIT LAW (A) 1821 eJ

t

D

H

+

∂

∂

=×∇

2. FARADAY’S INDUCTION LAW (F) 1831

t

B

E

∂

∂

−=×∇

3. GAUSS’ LAW – ELECTRIC (GE) ~ 1830

eD ρ=⋅∇

4. GAUSS’ LAW – MAGNETIC (GM) 0=⋅∇ B

André-Marie Ampère

1775-1836

Michael Faraday

1791-1867

Karl Friederich Gauss

1777-1855

James Clerk Maxwell

(1831-1879)

1865

Electromagnetism

MAXWELL UNIFIED ELECTRICITY AND MAGNETISM

Classical Theories](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-22-320.jpg)

![40

Physical Laws of RadiometrySOLO

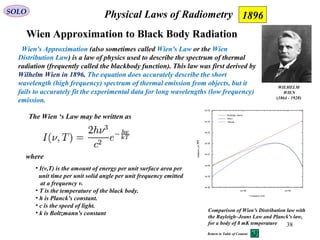

Rayleigh–Jeans Law

Comparison of Rayleigh–Jeans law with

Wien approximation and Planck's law, for

a body of 8 mK temperature

In 1900, the British physicist Lord Rayleigh derived

the λ−4

dependence of the Rayleigh–Jeans law based on

classical physical arguments.[3]

A more complete

derivation, which included the proportionality constant,

was presented by Rayleigh and Sir James Jeans in

1905. The Rayleigh–Jeans law revealed an important

error in physics theory of the time. The law predicted

an energy output that diverges towards infinity as

wavelength approaches zero (as frequency tends to

infinity) and measurements of energy output at short

wavelengths disagreed with this prediction.

John William Strutt,

3rd Baron Rayleigh

1842- 1919

James Hopwood Jeans

1877 - 1946

Rayleigh considered the radiation inside a cubic

cavity of length L and temperature T whose walls

are perfect reflectors as a series of standing

electromagnetic waves. At the walls of the cube, the

parallel component of the electric field and the

orthogonal component of the magnetic field must

vanish. Analogous to the wave function of a

particle in a box, one finds that the fields are

superpositions of periodic functions. The three

wavelengths λ1, λ2 and λ3, in the three directions

orthogonal to the walls can be: ,2,1,,

2

=== i

i

i

nzyxi

n

Lλ

1900 1905](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-40-320.jpg)

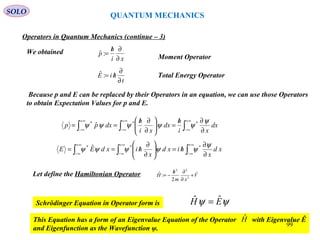

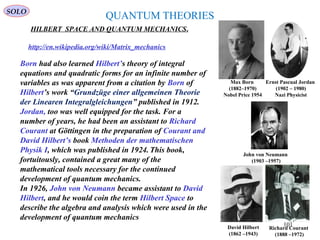

![QUANTUM THEORIES

Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, and Pascal Jordan formulate Quantum

Matrix Mechanics.

QUANTUM MATRIX MECHANICS.

Werner Karl Heisenberg

(1901 – 1976)

Nobel Price 1932

Max Born

(1882–1970)

Nobel Price 1954

Ernst Pascual Jordan

(1902 – 1980)

Nazi Physicist

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matrix_mechanics

1925

Matrix mechanics was the first conceptually autonomous and

logically consistent formulation of quantum mechanics. It extended the

Bohr Model by describing how the quantum jumps occur. It did so by

interpreting the physical properties of particles as matrices that evolve

in time. It is equivalent to the Schrödinger wave formulation of

quantum mechanics, and is the basis of Dirac's bra-ket notation for the

wave function.

SOLO

In 1928, Einstein nominated Heisenberg, Born, and Jordan for the

Nobel Prize in Physics, but Heisenberg alone won the 1932 Prize "for

the creation of quantum mechanics, the application of which has led to

the discovery of the allotropic forms of hydrogen",[47]

while

Schrödinger and Dirac shared the 1933 Prize "for the discovery of new

productive forms of atomic theory".[47]

On 25 November 1933, Born

received a letter from Heisenberg in which he said he had been delayed

in writing due to a "bad conscience" that he alone had received the

Prize "for work done in Gottingen in collaboration — you, Jordan and

I."[48]

Heisenberg went on to say that Born and Jordan's contribution

to quantum mechanics cannot be changed by "a wrong decision from

the outside." 78

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-78-320.jpg)

![Spin

In quantum mechanics and particle physics, Spin is an intrinsic form of angular

momentum carried by elementary particles, composite particles (hadrons), and

atomic nuclei. Spin is a solely quantum-mechanical phenomenon; it does not have a

counterpart in classical mechanics (despite the term spin being reminiscent of

classical phenomena such as a planet spinning on its axis).[

Spin is one of two types of angular momentum in quantum mechanics, the other

being orbital angular momentum. Orbital angular momentum is the quantum-

mechanical counterpart to the classical notion of angular momentum: it arises

when a particle executes a rotating or twisting trajectory (such as when an electron

orbits a nucleus).The existence of spin angular momentum is inferred from

experiments, such as the Stern–Gerlach experiment, in which particles are observed

to possess angular momentum that cannot be accounted for by orbital angular

momentum alone.[

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spin_(physics)

In some ways, spin is like a vector quantity; it has a definite “magnitude”; and it has

a "direction" (but quantization makes this "direction" different from the direction

of an ordinary vector). All elementary particles of a given kind have the same

magnitude of spin angular momentum, which is indicated by assigning the particle a

spin quantum number.[2]

However, in a technical sense, spins are not strictly vectors,

and they are instead described as a related quantity: a Spinor. In particular, unlike a

Euclidean vector, a spin when rotated by 360 degrees can have its sign reversed

QUANTUM MECHANICS

80](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-80-320.jpg)

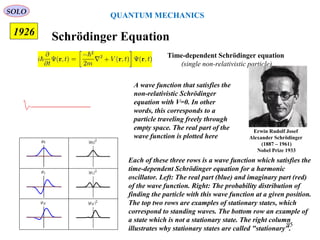

![ERWIN SCHRÖDINGER STAES THE NONRELATIVISTIC

QUANTUM WAVE EQUATION AND FORMULATES THE

QUANTUM MECHANICS. HE PROVES THAT WAVE AND

MATRIX FORMULATIONS ARE EQUIVALENT

1926

In January 1926, Schrödinger published in Annalen der Physik the paper

"Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem" [“Quantization as an Eigenvalue Problem”]

on wave mechanics and presented what is now known as the Schrödinger equation. In

this paper, he gave a "derivation" of the wave equation for time-independent systems

and showed that it gave the correct energy eigenvalues for a hydrogen-like atom. This

paper has been universally celebrated as one of the most important achievements of the

twentieth century and created a revolution in quantum mechanics and indeed of all

physics and chemistry. A second paper was submitted just four weeks later that solved

the quantum harmonic oscillator, rigid rotor, and diatomic molecule problems and

gave a new derivation of the Schrödinger equation. A third paper in May showed the

equivalence of his approach to that of Heisenberg.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erwin_Schr%C3%B6dinger

QUANTUM MECHANICS

Erwin Rudolf Josef

Alexander Schrödinger

(1887 – 1961)

Nobel Prize 1933

SOLO

81](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-81-320.jpg)

![MAX BORN GIVES A PROBABILISTIC INTERPRATATION

OF THE WAVE FUNCTION.

1926

Max Born

(1882–1970)

Nobel Price 1954

Max Born wrote in 1926 a short paper on collisions between particles,

about the same time as Schrödinger paper “Quantization as an

Eigenvalue Problem”. Born rejected the Schrödinger Wave Field

approach. He had been influenced by a suggestion made by Einstein

that, for photons, the Wave Field acts as strange kind of ‘phantom’ Field

‘guiding’ the photon particles on paths which could therefore be

determined by Wave Interference Effects.

Max Born reasoned that the Square of the Amplitude of the Waveform in some specific region

of configuration space is related to the Probability of finding the associated quantum particle in

that region of configuration space.

Since Probability is a real number, and the integral of all Probabilities over all regions of

configuration space, the Wave Function must satisfy

1*

=∫

+∞

∞−

dVψψ Condition of Normalization of the Wave Function

Therefore the probability of finding the particle

between a and b is given by

[ ] ( ) ( )∫=≤≤

b

a

xdxxbXaP ψψ *

Einstein rejected this interpretation. In a 1926 letter to Max Born, Einstein

wrote: "I, at any rate, am convinced that He [God] does not throw dice."[

QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

82

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-82-320.jpg)

![ERWIN SCHRÖDINGER STAES THE NONRELATIVISTIC

QUANTUM WAVE EQUATION AND FORMULATES THE

QUANTUM MECHANICS. HE PROVES THAT WAVE AND

MATRIX FORMULATIONS ARE EQUIVALENT

1926

Following Max Planck's quantization of light (see black body radiation),

Albert Einstein interpreted Planck's quanta to be photons, particles of light,

and proposed that the energy of a photon is proportional to its frequency, one

of the first signs of wave–particle duality. Since energy and momentum are

related in the same way as frequency and wavenumber in special relativity, it

followed that the momentum p of a photon is proportional to its wavenumber k.

c

k

h

hwherekh

h

p

c πν

λ

π

πλ

νλ 22

:,

2

:

/=

===//==

Louis de Broglie hypothesized that this is true for all particles, even particles such as electrons. He

showed that, assuming that the matter waves propagate along with their particle counterparts,

electrons form standing waves, meaning that only certain discrete rotational frequencies about the

nucleus of an atom are allowed.[7]

These quantized orbits correspond to discrete energy levels, and

de Broglie reproduced the Bohr model formula for the energy levels. The Bohr model was based on

the assumed quantization of angular momentum:

hn

h

nL /==

π2

According to de Broglie the electron is described by a wave and a whole number of wavelengths

must fit along the circumference of the electron's orbit: n λ = 2 π r

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schr%C3%B6dinger_equation

Historical Background and Development

QUANTUM MECHANICS

Erwin Rudolf Josef

Alexander Schrödinger

(1887 – 1961)

Nobel Prize 1933

SOLO

91](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-91-320.jpg)

![105

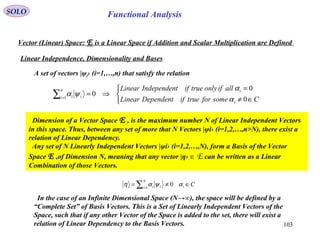

Functional AnalysisSOLO

Inner Product Using Dirac Notation

If E is a complex Linear Space, for the Inner Product (bracket) < | >

between the elements (a complex number) is defined by:

E∈∀ 321 ,, ψψψ

*

1221 || >>=<< ψψψψ1 Commutative Law

Using to we can show that:1 4

If E is an Inner Product Space, than we can induce the Norm: [ ] 2/1

111 , ><= ψψψ

2 Distributive Law><+>>=<+< 3121321 ||| ψψψψψψψ

3 C∈><>=< αψψαψψα 2121 ||

4

00|&0| 11111 =⇔>=<≥>< ψψψψψ

( ) ( ) ( )

><+><=><+><=>+<=>+< 1312

1

*

31

*

21

2

*

321

1

132 |||||| ψψψψψψψψψψψψψψ

( ) ( ) ( )

><=><=><=>< 21

*

1

*

12

*

3

*

12

1

21 |||| ψψαψψαψψαψαψ

( ) ( )

*

1

1

111

2

11 |000|0|0|00|0| ><=>=<⇒><+><=>+>=<< ψψψψψψ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-105-320.jpg)

![107

Functional Analysis

SOLO

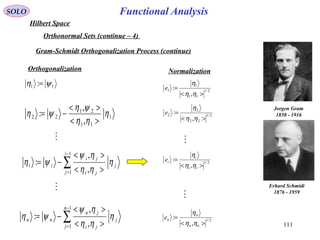

Hilbert Space

A Complete Space E is a Metric Space (in our case ) in which every

Cauchy Sequence converge to a limit inside E.

( ) 2121, ψψψψρ −=

David Hilbert

1862 - 1943

A Linear Space E is called a Hilbert Space if E is an Inner Product Space that is

complete with respect to the Norm induced by the Inner Product ||ψ1||=[< ψ1, ψ1>]1/2

.

Equivalently, a Hilbert Space is a Banach Space (Complete Metric Space) whose

Norm is induced by the Inner Product ||ψ1||=[< ψ1, ψ1>]1/2

.

Orthogonal Vectors in a Hilbert Space:

Two Vectors |η› and |ψ› are Orthogonal if 0|| == ηψψη

Theorem: Given a Set of Linearly Independent Vectors in a Hilbert

Space |ψi› (i=1,…,n) and any Vector |ψm› Orthogonal to all |ψi›,

than it is also Linearly Independent.

Proof: Suppose that the Vector |ψm› is Linearly Dependent on |ψi› (i=1,…,n)

∑=

=≠

n

i iim 1

0 ψαψ

But ∑=

==≠

n

i imimm 1

0

00

ψψαψψ

We obtain a inconsistency, therefore |ψm› is Linearly Independent on |ψi› (i=1,…,n)

Therefore in a Hilbert Space, of Finite or Infinite Dimension, by finding the Maximum

Set of Orthogonal Vectors we find a Basis that “Complete” covers the Space.

q.e.d.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-107-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

The condition that the probability of finding the particle somewhere to be unity, we deduce that

should be normalized to unity.( )tr,

Ψ

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )( )

∫ ∫∫

∫ ∫∫∫

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

⋅−//

∞+

∞−

−//−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

⋅−//−

+∞

∞−

⋅−//

ΦΦ

/

=

ΦΦ

/

=ΨΨ=

rpphitpEpEhi

rptpEhirptpEhi

erdetptppdpd

h

etppdetppdrd

h

trtrrd

'/3'/*33

3

/3''/*33

3

*3

,,''

2

1

,,''

2

1

,,1

π

π

Use

( )

( )( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( )( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )''''

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1 '/'/'/'/3

3

ppppppppezd

h

eyd

h

exd

h

erd

h

zzyyxx

zpphiypphixpphirpphi zzyyxx

−=−−−=

/

/

/

=

/ ∫∫∫∫

∞+

∞−

−//

∞+

∞−

−//∞+

∞−

−//

∞+

∞−

⋅−//

δδδδ

ππππ

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( )∫ ∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

−//−

−ΦΦ=ΨΨ ',,'',, '/*33*3

ppetptppdpdtrtrrd tpEpEhi

δ

Finally we obtain

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 1,,',, *3*3

=ΦΦ=ΨΨ ∫∫

+∞

∞−

tptppdtrtrrd

Return to Conservation

of Probability

Conservation of Probability

130](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-130-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

Conservation of Probability

SOLO

Since at any time t, the Probability of finding the particle somewhere is unity, and the

Probability of the particle being in the Momentum Space is unity we have

( ) ( ) ( ) 1,,, 3*3

=ΨΨ= ∫∫ rdtrtrrdtrP

( ) ( ) ( ) 1,,, 3*3

=ΦΦ=Π ∫∫ pdtptppdtp

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 0,,,,, 3**3

=

Ψ

∂

∂

Ψ+ΨΨ

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

∫∫ rdtr

t

trtrtr

t

rdtrP

t

Use Schrödinger equation : ( ) ( ) ctrV

m

h

tr

t

hi <<Ψ

−∇

/

=Ψ

∂

∂

/− v,

2

, 2

2

( ) ( ) ctrV

m

h

tr

t

hi

VV

<<Ψ

−∇

/

=Ψ

∂

∂

/

=

v,

2

, *2

2

*

*

and its conjugate:

Let consider a finite Region T in the Position Space:

Since: ( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( )trVtrtrtrVtrtrV ,,,,,, ****

ΨΨ=ΨΨ=ΨΨ

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) rdtrV

m

h

trtrtrV

m

h

hi

rdtrP

t

32

2

**2

2

3

,

2

,,,

2

1

, ∫∫ ΤΤ

Ψ

−∇

/

Ψ−ΨΨ

−∇

/

/

=

∂

∂

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]∫

∫∫

Ψ∇Ψ−ΨΨ∇⋅∇

/

=

Ψ∇Ψ−ΨΨ∇

/

=

∂

∂

T

TT

rdtrtrtrtr

im

h

rdtrtrtrtr

im

h

rdtrP

t

3**

32**23

,,,,

2

,,,,

2

,

131](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-131-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

Conservation of Probability

SOLO

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ∫∫∫ ⋅∇−=ΨΨ∇−Ψ∇Ψ⋅∇

/

−=

∂

∂

TTT

rdjrdtrtrtrtr

im

h

rdtrP

t

33**3

,,,,

2

,

where

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )[ ]trtr

m

h

trtrtrtr

im

h

j

,,Im

,,,,

2

:

*

**

Ψ∇Ψ

/

=

ΨΨ∇−Ψ∇Ψ

/

=

Since in the Equation above we have any time independent Spatial Volume T we can write

( ) ( ) 0,, =⋅∇+

∂

∂

trjtrP

t

Therefore is the Probability Current Density.( )trj ,

132

( ) ( ) ( ) rdtrtrrdtrP 3*3

,,,

ΨΨ= ( )trP ,

- Position Probability Density](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-132-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

Conservation of Probability

SOLO

The Probability Current Density is( )trj ,

133

Return to Table of Content

Connection with classical mechanics

The wave function can also be written in the complex exponential (polar) form

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) R∈=Ψ /

trStrRetrRtr htrSi

,,,,, /,

The Probability is defined as ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )trRtrtrtrP ,,,:, 2*

=ΨΨ=

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

∇

/

−∇−

∇

/

+∇

/

=

∇

/

−∇−

∇

/

+∇

/

=

∇−∇

/

=Ψ∇Ψ−Ψ∇Ψ

/

=

/−/−////−

/−///−

SR

h

i

RRSR

h

i

RR

im

h

SeR

h

i

ReeRSeR

h

i

ReeR

im

h

eReReReR

im

h

im

h

j

hSihSihSihSihSihSi

hSihSihSihSi

2

2

22

:

//////

////**

Therefore

m

S

j

∇

= ρ:

Define

m

Sj ∇

==

ρ

:v Probability Current Velocity

( ) ( ) ( )( ) 0,v,, =⋅∇+

∂

∂

trtrtrP

t

ρWe have Conservation of Probability](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-133-320.jpg)

![[ ] ABBABA −=:,

Commutator of two Operators A and B

[ ] [ ]ABBA ,, −=

[ ] [ ] [ ]CABACBA ,,, +=+

[ ] [ ] [ ]CABCBACBA ,,, +=

[ ][ ] [ ][ ] [ ][ ] 0,,,,,, =++ BACACBCBA

General Commutator Properties

If A B = B A we say that the two Operators A and B Commute, and then [A,B] = 0 .

In general A B ≠ B A and we say that A and B don’t commute.

Theorem: A and B Commute if and only if they have the same Eigenfunctions ψi

nibBaA iiiiii ,,1& === ψψψψ

Using Expansion Theorem any Vector

[ ] ( ) ( ) 0||,

0

11

=−Ψ=−Ψ=Ψ−Ψ=Ψ ∑∑ == iiiiii

n

i i

n

i iii abbaABBAABBABA ψψψψψψ

∑=

Ψ=Ψ

n

i ii1

ψψ

Proof: If A and B have the same Eigenfunctions ψi then

Therefore A and B Commute.

QUANTUM MECHANICS

Antisymmetry

Associativity

Jacobi Identity

SOLO

150](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-150-320.jpg)

![[ ] ABBABA −=:,

Commutator of two Operators A and B

Theorem: A and B Commute if and only if they have the same Eigenfunctions ψn

iii aA ψψ =Suppose that A have a complete set of Eigenfunctions

Proof (continue - 1): If A and B Commute, then they have the same Eigenfunctions ψn

then ( ) ( )ii

aA

i

ABBA

i BaABBA

iii

ψψψ

ψψ ==

==

Therefore Bψi and ψi are both Eigenfunctions of A, having the Eigenvalue ai, but this is

possible only if they differ by a constant which will call bi

iii bB ψψ =

Assume first that A has non-degenerate Eigenvalues ai

Therefore A and B have the same Eigenfunctions ψi , if ai are non-degenerate Eigenvalues. .

Now assume that A has a degenerate Eigenvalue ai, of degree α, with corresponding linearly

independent Eigenfunctions ψir (r=1,2,…,α). Since A B Commute (B ψi) is an Eigenfunction

of A belonging to the degenerated Eigenvalue ai. It follows that (B ψi) can be expanded in terms

of the linearly independent functions ψi1 , ψi2 ,…, ψiα

∑ =

=

α

ψψ 1s isisir cB

QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

151](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-151-320.jpg)

![[ ] ABBABA −=:,

Commutator of two Operators A and B

Theorem: A and B Commute if and only if they have the same Eigenfunctions ψi

Proof (continue - 2): If A and B Commute, then they have the same Eigenfunctions ψi

Therefore A and B have the same Eigenfunctions , even if ai are degenerate Eigenvalues. .

{ } nsrrss isrsir ccB ,,1,1 ==∑=

α

ψψ

Let form a linear combination of the functions ψir with α constants dr (r=1,2,…,α) to be

defined ∑ ∑∑ = ==

=

α αα

ψψ 1 11 r s isrsrr irr cddB

If we can find constants biβ (β=1,..,α) such that αβ

α

,,2,11

==∑ =

sdbcd sis rsr

Then and is an

Eigenfunction of B and by its structure, is also an Eigenfunction of A. To find α

Eigenfunctions and Eigenvalues we must solve

( ) ∑∑ ∑∑ == ==

==

α

β

α αα

ψψψ 11 11 s issis isr rsrr irr dbcddB ∑ =

α

ψ1r irrd

{ }( ) 0,,2,1

1

1

=

−⇒==∑ =

α

α

α

α

d

d

Ibcsdbcd iissis isr

We find α Eigenvectors (d1,…,dα)T

and Eigenvalues biβ of Matrix {cis}.

Now assume that A has a degenerate Eigenvalue ai, of degree α, , then

since AB Commute, (Bψir)is an Eigenfunction of A, and

( )αψψ ,,1 == raA iriir

QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

152](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-152-320.jpg)

![[ ] ABBABA −=:,

Commutator of two Operators A and B

Examples

xhipBxA x ∂∂/−=== /&

[ ] ( ) ( ) ψψ

ψ

ψψ hix

xx

xhixppxpx xxx /=

∂

∂

−

∂

∂

/−=−=,

In the same way [ ] [ ] ψψψψ hipzhipy zy /=/= ,&,

[ ] [ ] [ ] hipzhipyhipx zyx /=/=/= ,&,&,

1

3

t

hiEBtA

∂

∂

/=== &

[ ] ( ) ψψ

ψ

ψψ hit

tt

thitp

t

hitEt x /−=

∂

∂

−

∂

∂

/=

−

∂

∂

/=,

Since this is true for all State Vectors ψ

[ ] hiEt /−=,

QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

[ ] ( )[ ] ( ) ψψψψψ hirhirrhipr

I

/=∇/=∇−∇/−=

, [ ] hipr /=

,

∇/−=== hipBrA

&2

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] 0,,&0,,&0,, ====== yxzxzy pzpzpypypxpxalso

153

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-153-320.jpg)

![ΨΨ=ΨΨ= ||&|| BBAA

Heisenberg Uncertainty Relations

Consider two Observable A and B, and a given Normalized State |Ψ›.

We define the Uncertainties ∆A and ∆B (Observable Variances) as

1| =ΨΨ

( )[ ] ( )[ ] 2/122/12

:&: BBBAAA −=∆−=∆

( ) ( ) 222222

2 AAAAAAAAA −=+−=−=∆ ( ) 222

BBB −=∆

Define

0

~

&0

~

:

~

&:

~

==

−=−=

BA

BBBAAA

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]

000

,,,,,,,

~

,

~

BABABABABBABBABBAABA +−−=−−−=−−=

Define the Linear but no Hermitian Operator

BiAC

constBiAC

~~

:

~~

:

*

*

λ

λλλ

−=

==+=

Werner Karl Heisenberg

(1901 – 1976)

Nobel Price 1932

1927

The Expectations (Observables Main Values) of A and B are given by:

QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

154](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-154-320.jpg)

![Heisenberg Uncertainty Relations (continue – 1)

Define the Real and Nonnegative Function of λ

0||| ****

≥ΨΨ=ΨΨ=

Real

CCCCCC

( )( ) ( ) [ ]BAiBAABBAiBABiABiACC

~

,

~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 222222*

λλλλλλ −+=−−+=−+=

( ) [ ] [ ]

( ) ( ) [ ] 0,

~

,

~~~~

,

~~~

222

222222

≥−∆+∆=

−+=−+=

BAiBA

BAiBABAiBAf

λλ

λλλλλ

Since f (λ) is Real → i λ ‹[A,B]› is Real → ‹[A,B]› is Purely Imaginary → ‹[A,B]› 2

≤0

f (λ) has a nonnegative minimum for

[ ]

( )20

,

2 B

BAi

∆

=λ

( ) ( ) ( )

[ ]

( )

0

,

4

1

min 2

2

2

0 ≥

∆

+∆==

B

BA

Aff λλ ( ) ( ) [ ] 0,

4

1 222

≥−≥∆∆ BABA

QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

155](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-155-320.jpg)

![Heisenberg Uncertainty Relations (continue – 2)

Since ∆A and ∆B are real and positive, we found

[ ]BABA ,

2

1

≥∆⋅∆

and

Therefore

2

&

2

&

2

h

pz

h

py

h

px zyx

/

≥∆⋅∆

/

≥∆⋅∆

/

≥∆⋅∆

2

h

Et

/

≥∆⋅∆

Heisenberg Uncertainty

Relation for Simultaneous

Position & Momentum

Measurements

Heisenberg Uncertainty

Relation for Simultaneous

Time & Energy

Measurements

1 [ ] [ ] [ ] hipzhipyhipx zyx /=/=/= ,&,&,

2 [ ] hiEt /−=,

QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

156](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-156-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

The Schrödinger and Heisenberg Pictures (continue – 2)

Werner Karl Heisenberg

(1901 – 1976)

Nobel Price 1932

Erwin Rudolf Josef

Alexander Schrödinger

(1887 – 1961)

Nobel Prize 1933

( ) ( )UtAUtA S

H

H =

( ) ( )tttU S

H

H ψψ 0,=

( ) ( )00 ,ˆ, ttUHttU

t

hi =

∂

∂

/

( ) ( ) ( )

H

HHHHH

t

A

HAAHhitA

td

d

∂

∂

++−/=

− ˆˆ1

We obtained

UHUH H

H

ˆ:ˆ =

( )U

t

tA

U

t

A SH

H

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

:

Using the Commutator definition , we obtain[ ] HHHHHH AHHAHA ˆˆ:ˆ, −=

( ) ( ) [ ]

H

HHH

t

A

HAhitA

td

d

∂

∂

+/=

− ˆ,

1

This is Heisenberg Equation of Motion for the Operator AH.

SOLO

169

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-169-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )trtprA

t

trtrtprHtprAtprAtprHtr

h

i

tA

td

d

,ˆ|,ˆ,ˆ|,ˆ,ˆ|,ˆ,ˆˆ,ˆ,ˆ,ˆ,ˆ,ˆ,ˆˆ|,ˆ

ψψψψ

∂

∂

+−

/

=

or

( ) [ ] ψψψψ |||ˆ,|

1

A

t

HA

hi

tA

td

d

∂

∂

+

/

=

where Commutator of H and A.[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )tprAtprHtprHtprAHA ,ˆ,ˆ,ˆ,ˆˆ,ˆ,ˆˆ,ˆ,ˆ:,

−=

We obtain

The previous equation can be written (shorthand notation) as

( ) [ ] A

t

HA

hi

tA

td

d

∂

∂

+

/

= ˆ,

1

Transition from Quantum Mechanics to Classical Mechanics.

171](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-171-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

( )

( )

∂

∂

−=

∂

∂

=

r

tprH

td

pd

p

tprH

td

rd

,,

,,

In Classical Mechanics the Equation of Motion of a Particle of mass m can be described

Using Hamilton-Jacobi Canonical Equations

Transition from Quantum Mechanics to Classical Mechanics.

where is the Hamiltonian( ) ( )trV

m

pp

tprH ,

2

:,,

+

⋅

=

To see this

( )

( ) ( )

=

∂

∂

−=

∂

∂

−=

==

∂

∂

=

=

F

r

trV

r

tprH

td

pd

m

p

p

tprH

td

rd mp

,,,

v

,, v

For any differentiable function we have( )tprA ,,

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

t

tprA

r

tprH

p

tprA

p

tprH

r

tprA

t

tprA

td

pd

p

tprA

td

rd

r

tprA

tprA

td

d

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

∂

∂

−

∂

∂

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

=

,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,

,,

Define Poisson Brackets{ } ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

r

tprH

p

tprA

p

tprH

r

tprA

HA

∂

∂

∂

∂

−

∂

∂

∂

∂

=

,,,,,,,,

:,

( ) { } ( )

t

tprA

HAtprA

td

d

∂

∂

+=

,,

,,,

Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi

(1804-1851)

William Rowan Hamilton

(1805-1855)

Siméon Denis

Poisson

1781-1840

172We see that to go from Classical to Quantum we must replace the Poisson Brackets { }with

the Commutator [ ] multiplied by .( )hi //1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-172-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

We obtained

Let compute ( ) [ ] ( )

[ ] [ ] [ ]

( )[ ]trVr

him

p

r

hi

trV

m

p

r

hi

r

t

Hr

hi

tr

td

d CBCACBA

,,

1

2

,

1

,

2

,

1ˆ,

1 2,,,2

0

/

+

/

=

+

/

=

∂

∂

+

/

=

+=+

[ ]

[ ] [ ] [ ]

[ ] [ ] p

m

prpppr

him

ppr

himm

p

r

hi hihi

CABCBABCA

1

,,

2

1

,

2

1

2

,

1 ,,,2

=+

/

=⋅

/

=

/ ////

+=

( )[ ] ( ) ( ) 0,,

1

,,

1

=−

/

=

/

rtrVtrVr

hi

trVr

hi

Therefore ( ) ptr

td

d

m

=

( ) [ ] A

t

HA

hi

tA

td

d

∂

∂

+

/

= ˆ,

1

Transition from Quantum Mechanics to Classical Mechanics.

173](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-173-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

In the same way ( ) [ ] ( )

[ ] [ ] [ ]

( )[ ]trVp

him

pp

p

hi

trV

m

p

p

hi

p

t

Hp

hi

tp

td

d CBCACBA

,,

1

2

,

1

,

2

,

1ˆ,

1 ,,,2

0

/

+

⋅

/

=

+

/

=

∂

∂

+

/

=

+=+

[ ]

[ ] [ ] [ ]

[ ] [ ] 0,,

2

1

,

2

1

00

,,,

=+

/

=⋅

/

+=

pppppp

him

ppp

him

CABCBABCA

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )( ) ( )∫∫ ∇+∇−=∇/−

/

=

/

ψψψψ trVrdtrVrdtrVhi

hi

trVp

hi

,,,,

1

,,

1 *3*3

( )( ) ( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( ) FtrVtrVrdtrVrdtrVrdtrVrd

=∇−=∇−=∇+∇−∇−= ∫∫∫∫ ,,,,, *3*3*3*3

ψψψψψψψψ

Therefore ( ) ( ) FtrVtp

td

d

=∇−= ,

Transition from Quantum Mechanics to Classical Mechanics.

174](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-174-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

Time Independent Hamiltonian

Transition from Quantum Mechanics to Classical Mechanics.

Assume a Time Independent Hamiltonian H

=

∂

∂

0

ˆ

t

H

than choosing in the equationHA ˆ=

( ) [ ] A

t

HA

hi

tA

td

d

∂

∂

+

/

= ˆ,

1

we obtain

( ) [ ] 0ˆˆ,ˆˆ

0

0

=

∂

∂

+

/

=

H

t

HH

h

i

tH

td

d

Since the Total Energy is a Constant of Motion. This is the analogue to

Conservation of Energy in Classical Mechanics.

EH ˆˆ =

( ) ( ) ( )prErV

m

pp

prH

,

2

:, =+

⋅

=

( ) ( ) { } ( ) 0

,

,,,

0

0

=

∂

∂

+==

t

prH

HHprH

td

d

prE

td

d

176](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-176-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

Virial Theorem

Transition from Quantum Mechanics to Classical Mechanics.

Assume a Time Independent Operator in the equation( ) prprA ˆˆ,

⋅=

( ) [ ]

0

ˆ,

1

A

t

HA

hi

tA

td

d

∂

∂

+

/

=

Assume also a Time Independent Hamiltonian, whose Eigenfunctions are given using

( ) ( ) ( )trEtrprH HnnHn ,,,ˆ

Ψ=Ψ

Schrödinger Equation for |ψ(t)› is ( ) ( ) ( )trprH

h

i

tr

t

HH ,,ˆ,

ψψ

/

−=

∂

∂

( ) ( ) HEertr htEi

HH == /−

,0,, /

ψψ

Using those Eigenfunction we can calculate

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑∫∑∫ === −

n

HnHn

n

tEi

Hn

tEi

HnHH rprArrderprAerrdAA 0,,0,0,,0,|| *3*3

ψψψψψψ

We can see that if A is not an explicit function of time then <A> is Time Independent

( ) 0=tA

td

d

177](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-177-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

Virial Theorem

Transition from Quantum Mechanics to Classical Mechanics.

Assume a Time Independent Operator in the equation

[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]rVpr

m

pp

prrV

m

pp

prHpr

,ˆˆ

2

ˆˆ

,ˆˆˆ

2

ˆˆ

,ˆˆˆ,ˆˆ ⋅+

⋅

⋅=

+

⋅

⋅=⋅

[ ] [ ]( ) [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] m

pp

hipprpprpppprppr

m

pprppppr

mm

pp

pr

hihi

ˆˆ

ˆˆ,ˆˆ,ˆˆˆˆˆˆ,ˆˆ,ˆˆ

2

1ˆ,ˆˆˆˆˆ,ˆˆ

2

1

2

ˆˆ

,ˆˆ

00

⋅

/=

+⋅+⋅

+=⋅⋅+⋅⋅=

⋅

⋅

//

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )rVrhirVhirprVrrVprrVpr

∇/−=∇/−=+=⋅ ,ˆ,,ˆˆ,ˆ,ˆ,ˆ,ˆˆ

0

( ) prprA ˆˆ,

⋅=

( ) [ ]

0ˆ,

1

0

=

∂

∂

+

/

= A

t

HA

hi

tA

td

d

We obtain

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )( ) ( )( ) ( )( )∫∫∫ ∇/−=∇−∇/−=∇/−=∇/− ψψψψψψ rVrdhirVrdrVrdhirVhirVhi

*3*3*3

,,

[ ] ( ) 0ˆ

2

ˆˆ

2ˆ,ˆˆ =∇⋅/−

⋅

/=⋅ rVrhi

m

pp

hiHpr

T

where we used

( )rVrT

∇⋅=2 Virial Theorem 178

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-178-320.jpg)

![08/13/15 187

SOLO

Non-relativistic Schrödinger Equation in an Electromagnetic Field

Electromagnetic Field

In Quantum Mechanics an electron, with no external electromagnetic field presented, is

expressed by a wave function ψ that satisfies the Schrödinger Equation:

( ) ( ) ( )rtprH

t

rt

hi

,,

,

ψ

ψ

=

∂

∂

/

( ) ( ) ( )rV

m

rtp

prH

+=

2

,

:,

2

where Hamiltonian

and is Canonical Momentum, and is represented by the differential operatorp

∇/−= hipˆ - Momentum Operator ( - del Operator)∇

The Schrödinger Equation:

( ) ( ) ( )rtVrt

m

h

t

rt

hi

,,

2

, 2

2

ψψ

ψ

+∇

/

−=

∂

∂

/

AB

t

A

c

E

×∇=∇−

∂

∂

−= ,

1

ϕIf an external Electromagnetic Field :

is presented, we must replace

BE

,

ϕeVVA

c

e

pp +→−→ &

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )rtrterVrt

c

rtA

h

ei

m

h

t

rt

hi

,,,

,

2

,

2

2

ψϕψ

ψ

++

/

−∇

/

−=

∂

∂

/

Schrödinger Equation in

an Electromagnetic Field

( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( )rterV

m

rtA

c

e

rtp

prH

,

2

,,

:,

2

ϕ++

−

=

to obtain Non-relativistic Hamiltonian in

an Electromagnetic Field](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-187-320.jpg)

![08/13/15 188

SOLO

Electromagnetic Field

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )rtrterVrtrtA

c

e

i

h

mt

rt

hi

,,,,

2

1,

2

ψϕψ

ψ

++

−∇

/

=

∂

∂

/ Schrödinger Equation in

an Electromagnetic Field

xi

h

p

∂

∂/

=:ˆUsing the Momentum Operator we can write

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )rtrterVrtA

c

e

p

mt

rt

hi

,,,ˆ

2

1,

2

ψϕ

ψ

++

−=

∂

∂

/

Schrödinger Equation in

an Electromagnetic Field

Non-relativistic Schrödinger Equation in an Electromagnetic Field

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-188-320.jpg)

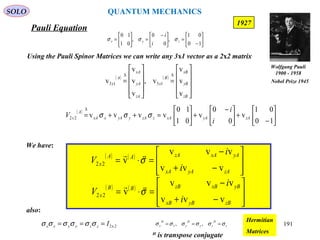

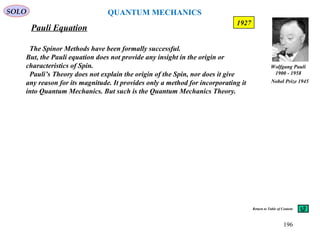

![Pauli Equation

SOLO

Pauli Equation or Schrödinger–Pauli equation is the formulation of the

Schrödinger equation for spin-½ particles, which takes into account the

interaction of the particle's spin with an external electromagnetic field. It is the

non-relativistic limit of the Dirac equation and can be used where particles are

moving at speeds much less than the speed of light, so that relativistic effects can

be neglected. It was formulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1927.

193

1927

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )rtrterVrtA

c

e

p

mt

rt

hi

,,,ˆ

2

1,

2

ψϕ

ψ

++

−=

∂

∂

/

Schrödinger Equation in an

Electromagnetic Field

for a spinless particle

For a particle of mass m, charge e, and without spin, in an electromagnetic field described

by the vector potential A = (Ax, Ay, Az) and scalar electric potential φ, and in a conservative

external field described by the potential ,the Schrödinger equation is:( )rV

where σ = (σx, σy, σz) are the Pauli matrices collected into a tensor for convenience, p = −iħ is∇

the momentum operator wherein denotes the gradient operator, and∇

is the two-component Spinor Wave Function, a column vector written in Dirac notation.

=

−

+

2/1

2/1

1x2

ψ

ψ

ψ

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )rtrterVIrtA

c

e

p

mt

rt

hi

,,,ˆ

2

1,

2x2

2

ψϕσ

ψ

++

−⋅=

∂

∂

/

Pauli- Schrödinger Equation in an

Electromagnetic Field for a particle

with Spin 2/h/±

For a particle of mass m ,charge e, spin in an electromagnetic field described by the

vector potential A = (Ax, Ay, Az) and scalar electric potential , and scalar electric potential ,ϕ ϕ

and in a conservative external field described by the potential ,the Pauli equation is:( )rV

2/h/±

Wolfgang Pauli

1900 - 1958

Nobel Prize 1945

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-193-320.jpg)

![Pauli Equation

SOLO

194

The Hamiltonian operator is

is a 2 × 2 matrix operator, because of the Pauli matrices. Substitution into the

Schrödinger equation

gives the Pauli equation.

1927

ψψ EH ˆˆ =

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

++

−⋅= rterVIrtA

c

e

p

m

H

,,ˆ

2

1

:ˆ

2x2

2

2x2 ϕσ

t

IhiE

∂

∂

/= 2x22x2 :ˆ

The Pauli matrices can be removed from the kinetic energy term, using the Pauli vector

identity:

Let develop

( )( ) ( ) ( )21222121

ˆˆˆˆˆˆ nniInnnn x ×⋅+⋅=⋅⋅ σσσ

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

i

hp

AA

pAeipAeApeiApe

pp

i

hAA

i

h

c

e

iA

c

e

pA

c

e

p

AA

c

e

pA

c

e

Ap

c

e

ppA

c

e

p

∇

/=

⋅

×⋅+⋅×⋅+⋅

⋅

∇

/×+×

∇

/⋅−

−⋅

−=

⋅⋅⋅

+⋅⋅⋅−⋅⋅⋅−⋅⋅⋅=

−⋅

ˆ

2

ˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

2

ˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆ

σ

σσσσσσσσσ

σσ

Wolfgang Pauli

1900 - 1958

Nobel Prize 1945

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-194-320.jpg)

![Pauli Equation

SOLO

195

where B = × A is the magnetic field.∇

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )rtrterVIrtArtAh

c

e

rtA

c

e

rtp

m

rtrterVIrtA

c

e

rtp

mt

rt

hi

,,,,,,ˆ

2

1

,,,,ˆ

2

1,

2x2

2

2x2

2

ψϕσ

ψϕσ

ψ

++

∇×+×∇⋅/−

−=

++

−⋅=

∂

∂

/

Pauli- Schrödinger Equation in an Electromagnetic Field for a particle

with Spin 2/h/±

( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )rtrtArtArtrtArt

rtrtArtrtArtrtArtA

,,,,,,

,,,,,,,

ψψψ

ψψψ

∇×+×∇+×∇=

∇×+×∇=∇×+×∇

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )rtrterVIrtB

cm

he

rtA

c

e

rtp

mt

rt

hi

,,,

2

,,ˆ

2

1,

2x2

2

ψϕσ

ψ

++⋅

/

−

−=

∂

∂

/

Pauli- Schrödinger Equation in an Electromagnetic Field for a particle with Spin 2/h/±

and the Hamiltonian is

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]rterVIrtB

cm

he

rtA

c

e

rtp

m

rtH

,,

2

,,ˆ

2

1

:, 2x2

2

ϕσ ++⋅

/

−

−=

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )rtBrtrtArt

,,,, ψψ =×∇=

Wolfgang Pauli

1900 - 1958

Nobel Prize 1945

1927

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-195-320.jpg)

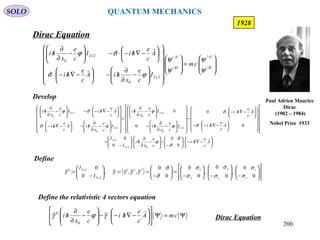

![204

Dirac Equation

SOLO

1928

Ψ=Ψ

−∇/−⋅−

−

∂

∂

/ cmA

c

e

hi

c

e

x

hi

γϕγ

0

0

Dirac Equation

Let multiply this equation by and using0

γ

c

4x4

2x2

2x2

2x2

2x200

0

0

0

0

I

I

I

I

I

=

−

−

=γγ

=

−

−

=

0

0

0

0

0

0

2x2

2x20

σ

σ

σ

σ

γγ

I

I

we obtain

( )

Ψ=Ψ

−∇/−⋅−

−

∂

∂

/ 02000

γγγϕγγ

cmA

c

e

hic

c

e

tc

hic

rearranging we obtain

( )[ ] Ψ=Ψ++−∇/−⋅=Ψ

∂

∂

/ 4x4

20000 ˆHcmeAehci

t

hi γϕγγγγ

where the 4x4 Hamiltonian is defined as

( )[ ]20000

4x4 :ˆ cmeAehciH γϕγγγγ

++−∇/−⋅=

( )

( )

=Ψ

1x2

1x2

:1x4 B

A

ψ

ψ

Paul Adrien Maurice

Dirac

(1902 – 1984)

Nobel Prize 1933

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-204-320.jpg)

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

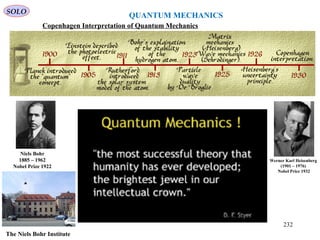

Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

The Copenhagen interpretation is one of the earliest and most commonly taught

interpretations of quantum mechanics.[1]

It holds that quantum mechanics does not yield

a description of an objective reality but deals only with probabilities of observing, or

measuring, various aspects of energy quanta, entities that fit neither the classical idea of

particles nor the classical idea of waves. The act of measurement causes the set of

probabilities to immediately and randomly assume only one of the possible values. This

feature of the mathematics is known as wavefunction collapse. The essential concepts of

the interpretation were devised by Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and others in the years

1924–27.

There are several basic principles that are generally accepted as being part of the

interpretation:

1. A system is completely described by a wave function Ψ, representing the state of the

system, which evolves smoothly in time, except when a measurement is made, at which

point it instantaneously collapses to an eigenstate of the observable that is measured.

2. The description of nature is essentially probabilistic, with the probability of a given

outcome of a measurement given by the square of the modulus of the amplitude of the

wave function. (The Born rule, after Max Born)

SOLO

233](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-233-320.jpg)

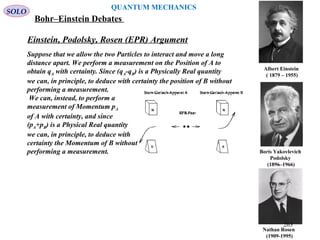

![Nathan Rosen

(1909-1995)

Boris Yakovlevich

Podolsky

(1896–1966)

Albert Einstein

(/1879 – 1955)

Einstein, Podolsky, Rosen (EPR) Argument

Let denote the two Particles by A and B.

The Position qA and Momentum pA of Particle A are complementary

observables and we cannot measure one without introducing an

uncertainty in the other according to Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.

Similar for qB and pB of Particle B.

SOLO

[ ] [ ] hipqpq BBAA /== ˆ,ˆˆ,ˆ

Since A and B are different

Quantum Particles we also have

[ ] [ ] 0ˆ,ˆˆ,ˆ == ABBA pqpq

Now consider the quantities BABA ppPqqQ ˆˆ:ˆ&ˆˆ:ˆ +=−=

Let compute the Commutator

[ ] ( )( ) ( )( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] 0ˆ,ˆˆ,ˆˆ,ˆˆ,ˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ,ˆ

00

=−−+=

−−−−−+−=

−+−−−−+=

−+−+−=−=

//

hi

BBABBA

hi

AA

BBBBBAABABBAAAAA

BBABBAAABBABBAAA

BABABABA

pqpqpqpq

qppqqppqqppqqppq

qpqpqpqppqpqpqpq

qqppppqqQPPQPQ

Hence , the Operators commute, therefore we can

measure the Difference between Positions of Particles A and B and the

Sum of their Moments with high precision. Q and P are therefore

Physically Real Quantities.

[ ] 0ˆ,ˆ =PQ PandQ ˆˆ

QUANTUM MECHANICS

Bohr–Einstein Debates

262](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-262-320.jpg)

![Path Integral Representation of Time Evolution Amplitudes

SOLO

The Path Integral approach to Quantum Mechanics was developed by Feynman in 1948.

Richard Feynman

(1918 – 1988)

Nobel Prize 1965

The Path Integral formulation of Quantum Mechanics is a description

of Quantum Theory which generalizes the Action Principle of Classical

Mechanics. It replaces the classical notion of a single, unique trajectory

for a system with a sum, or functional integral, over an infinity of

possible trajectories to compute a quantum amplitude.

The basic idea of the path integral formulation can be traced back to Norbert Wiener,

who introduced the Wiener integral for solving problems in diffusion and Brownian

motion.[1]

This idea was extended to the use of the Lagrangian in quantum mechanics by P.

A. M. Dirac in his 1933 paper.[2]

The complete method was developed in 1948 by Richard

Feynman. Some preliminaries were worked out earlier, in the course of his doctoral thesis

work with John Archibald Wheeler. The original motivation stemmed from the desire to

obtain a quantum-mechanical formulation for the Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory

using a Lagrangian (rather than a Hamiltonian) as a starting point.

1948QUANTUM MECHANICS

268](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-268-320.jpg)

![Path Integral Representation of Time Evolution Amplitudes

SOLO

Richard Feynman

(1918 – 1988)

Nobel Prize 1965

1948

The Transition Amplitude for the entire time period is

( )∏ ∑∫

−

=

−

=

+

−

−

/

/−

=

/

−=

1

1

1

0

2

1

2

0

2

1

exp

2

ˆexp

N

j

N

j j

jj

j

N

qV

t

qq

mt

h

i

qd

t

hmi

qtH

h

i

FF

δ

δ

δπ

ψ

By taking the limit of large N the Transition Amplitude reduces to

( )∫

/

=

/

−= S

h

i

tqDqtH

h

i

FF expˆexp 0ψ

( ) ( )[ ]∫=

T

tqtqLtdS

0

, where S is the classical action given by

and L is the classical Lagrangian given by ( ) ( )[ ] ( )qVqmtqtqL −= 2

2

1

,

Any possible path of the particle, going from the initial state to the final state, is

approximated as a broken line and included in the measure of the integral

( ) ( )∏ ∫∫

−

=∞→

/

−

=

1

1

2

2

lim

N

j j

N

N

qd

th

mi

tqD

δπ

This expression actually defines the manner in which the path integrals are to be taken.

The coefficient in front is needed to ensure that the expression has the correct dimensions,

but it has no actual relevance in any physical application.

QUANTUM MECHANICS

272](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-272-320.jpg)

![Bell's Theorem

Bell considers the same experiment but focuses on correlations

between results of spin measurement at different orientation of the two

magnets.

He then shows that the correlations predicted by quantum mechanics

cannot be generated by local hidden parameters:

Quantum mechanics => There can't be local hidden parameters.

Bell:

Together with the EPR argument, this entails that either quantum mechanics makes wrong

predictions or locality does not hold. Since (most of) the experiments confirm the quantum

prediction, we conclude:

Bell + EPR + experiment=>Nature is nonlocal. There is instantaneous action-at-a-distance

Oct 15, 1997. Written by students of the Bohmian mechanics group.

http://www.mathematik.uni-muenchen.de/~bohmmech/Poster/post/postE.html

John Stewart Bell

(1928 – 1990)

Bell's theorem, derived in his seminal 1964 paper titled On the Einstein

Podolsky Rosen paradox,[5]

has been called, on the assumption that the

theory is correct, "the most profound in science".[11]

Perhaps of equal

importance is Bell's deliberate effort to encourage and bring legitimacy to

work on the completeness issues, which had fallen into disrepute

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell%27s_theorem

John Stewart Bell, "On the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox", Physics 1, (1964) 195-200. Reprinted

in Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

SOLO

1964

289

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-289-320.jpg)

![Bell's Theorem

SOLO

1964

Bell considered three theoretical experiences with correlated photons. In each experience

a Source emitted two correlated photons in two opposite directions to two optical aligned

Polarization Analyzers PA1 and PA2. The Polarization Analyzers PA1 and PA2, in those

experiments are in three possible orientations

(a)φ = 0º

(b)φ = 22.5º

(c)φ = 45º

Source

v͛

h͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation b (ϕ =22.5)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation a (ϕ=0)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience 1

Source

v͛͛

h͛͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation c (ϕ =45)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation a (ϕ=0)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience2

Source

v͛͛

h͛͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation c (ϕ =45)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation b (ϕ=22.5)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience 3

Bell’s Theorem checks the validity of EPR conjunction that the to explain the entanglement of

quantum particle, there must exist locally hidden variables that communicate between the

entangled particles at speeds less than speed of light.

Let perform the same large number M of experiments 1, 2 and 3 and for each orientation (a),

(b) and (c) count the separately the detections in Vertical (v) and Horizontal (h) channels.

Let define

N [av], N[ah] - Number of detections in v channels, and in h channels in (a) orientation in

experiments 1 and 2

N [bv], N[bh] - Number of detections in v channels, and in h channels in (b) orientation in

experiments 1 and 3

N [cv], N[ch] - Number of detections in v channels, and in h channels in (c) orientation in

290

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-290-320.jpg)

![Bell's Theorem

SOLO

1964

Source

v͛

h͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation b (ϕ =22.5)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation a (ϕ=0)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience 1

Source

v͛͛

h͛͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation c (ϕ =45)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation a (ϕ=0)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience2

Source

v͛͛

h͛͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation c (ϕ =45)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation b (ϕ=22.5)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience 3

Since in the 3 experiments we have two Polarizations Analyzers in the same orientation, and

since we assume that each photon will be detected in the Vertical v or the Horizontal h channel,

and we perform M measurements in each experience we ca write

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] McNcNbNbNaNaN 2hvhvhv =+=+=+

For large number of M measurements we can write

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]

M

aN

aP

M

aN

aP

MM 2

lim,

2

lim h

h

v

v

∞→∞→

== Probabilities of detections in v channels, and in h

channels in (a) orientation in experiments 1 and 2

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]

M

bN

bP

M

bN

bP

MM 2

lim,

2

lim h

h

v

v

∞→∞→

== Probabilities of detections in v channels, and in h

channels in (b) orientation in experiments 1 and 3

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]

M

cN

cP

M

cN

cP

MM 2

lim,

2

lim h

h

v

v

∞→∞→

== Probabilities of detections in v channels, and in h

channels in (c) orientation in experiments 2 and 3

291

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-291-320.jpg)

![Bell's Theorem

SOLO

1964

Source

v͛

h͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation b (ϕ =22.5)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation a (ϕ=0)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience 1

Source

v͛͛

h͛͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation c (ϕ =45)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation a (ϕ=0)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience2

Source

v͛͛

h͛͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation c (ϕ =45)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation b (ϕ=22.5)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience 3

Since we assume local reality, the measurements in the orientations (a), (b) and (c) are

independent, therefore we can write

P [av,bh] = P [av]* P[bh] - Probability of joint detections in v channel in (a) orientation and in

h channel in (b) orientations in all 3 experiments.

P [bv,ch] = P [bv]* P[ch] - Probability of joint detections in v channel in (b) orientation and in

h channel in (c) orientations in all 3 experiments.

P [av,ch] = P [abv]* P[ch] - Probability of joint detections in v channel in (a) orientation and in

h channel in (c) orientations in all 3 experiments.

Also

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]( ) [ ] [ ]vhvhhv

1

vhhvhv ,,,,,, cbaPcbaPcPcPbaPbaP +=+⋅=

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]( ) [ ] [ ]hhvhvvhvhvhv ,,,,,, cbaPcbaPbPbPcaPcaP +=+=

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]( ) [ ] [ ]hvhhvvhvhvhv ,,,,,, cbaPcbaPaPaPcbPcbP +=+⋅=

[ ] [ ]hhvhv ,,, cbaPbaP ≥

[ ] [ ]hvvhv ,,, cbaPcbP ≥

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]

[ ]

[ ]hv

,

hvvhhvhvhv ,,,,,,,

hv

caPcbaPcbaPcbPbaP

caP

=

+≥+

292

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-292-320.jpg)

![Bell's Theorem

SOLO

1964

Source

v͛

h͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation b (ϕ =22.5)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation a (ϕ=0)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience 1

Source

v͛͛

h͛͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation c (ϕ =45)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation a (ϕ=0)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience2

Source

v͛͛

h͛͛

Polarization Analyzer2 (PA2)

Orientation c (ϕ =45)

v

h

Polarization Analyzer1 (PA1)

Orientation b (ϕ=22.5)

BA

Left

Polarization

Photons

Right

Polarization

Photons

Experience 3

Bell's Inequality[ ] [ ] [ ]hvhvhv ,,, caPcbPbaP ≥+

For chosen

(a) φ = 0º

(b) φ = 22.5º

(c) φ = 45º

( ) ( )abbaP −∠== ϕϕ,sin

2

1

, 2

hv'Using Quantum Theory we found

( ) ( ) ( )

45sin

2

1

5.22sin

2

1

5.22sin

2

1 222

≥+

or which is incorrect2500.01464.0 ≥

Quantum Theory is incompatible with any Local Hidden Variable Theory.

Conclusion of Bell's Inequality

There is more than one Inequality that are collectively known as Bell's Inequality.

All of them give the same conclusion. 293

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-293-320.jpg)

![Bell_Test_Experiments

SOLO

John Francis Clauser

Born 1942

CHSH (Clauser, Horn, Shimony, Holt ) Inequality

Abner Shimony

Born 1928

CHSH inequality can be used in the proof of Bell's theorem, which

states that certain consequences of entanglement in quantum

mechanics cannot be reproduced by local hidden variable theories.

Experimental verification of violation of the inequalities is seen as

experimental confirmation that nature cannot be described by local

hidden variables theories. CHSH stands for John Clauser, Michael

Horne, Abner Shimony and Richard Holt, who described it in a

much-cited paper published in 1969 (Clauser et al., 1969).[1]

They

derived the CHSH inequality, which, as with John Bell’s original

inequality (Bell, 1964),[2]

is a constraint on the statistics of

"coincidences" in a Bell test experiment which is necessarily true if

there exist underlying local hidden variables (local realism). This

constraint can, on the other hand, be infringed by quantum

mechanics

Richard Holt

Michael Horne

1969

296

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-296-320.jpg)

![Bell_Test_Experiments

SOLO

CHSH (Clauser, Horn, Shimony, Holt ) Inequality 1969

The expectation value for the joint measurement of A and B is

E (a,b,λ) = A (a,λ) B (b,λ)

Let average tis result over all Hidden Variable λ, by performing enough

measurements to cover all values of λ.

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫ ⋅⋅⋅= λλρλλ dbBaAbaE ,,,

We also can write

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )∫

∫

⋅⋅−⋅=

⋅⋅⋅−⋅=−

λλρλλλ

λλρλλλλ

ddBbBaA

ddBaAbBaAdaEbaE

,,,

,,,,,,

Since |A (a,λ)| ≤ 1 we have

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫ ⋅⋅−≤− λλρλλ ddBbBdaEbaE ,,,,

Similarly ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫ ⋅⋅+≤+ λλρλλ ddBbBdcEbcE ,,,,

Combining those two equations we obtain

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )∫ ⋅⋅−+−≤++− λλρλλλλ ddBbBdBbBdcEbcEdaEbaE ,,,,,,,,

Since |B (b,λ)| ≤ 1 we have ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 2,,,, ≤−+− λλλλ dBbBdBbB

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 22,,,,

1

=⋅≤++− ∫

λλρ ddcEbcEdaEbaE CHSH Inequality

298

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-298-320.jpg)

![Bell_Test_Experiments

SOLO

Alain Aspect (Born 1947)

on a visit to Tel Aviv

University in 2010

Scheme for 1981 Experiment, P's polarisers and D's

detectors. Polariser axes are at angles a and b

respectively.

The diagram shows a typical optical experiment of the two-channel

kind for which Alain Aspect set a precedent in 1982.[2]

Coincidences

(simultaneous detections) are recorded, the results being categorised

as '++', '+−', '−+' or '−−' and corresponding counts accumulated.

Scheme of a "two-channel" Bell test

The source S produces pairs of "photons", sent in opposite directions. Each photon

encounters a two-channel polariser whose orientation can be set by the experimenter.

Emerging signals from each channel are detected and coincidences counted by the

coincidence monitor CM.

In 1982, a group led by, the French physicist Alain Aspect at the University

of Paris-South, carried out Bohm's experiment, demonstrating once and

for all that quantum mechanics does indeed require spooky action. (The

reason that nonlocality does not violate the theory of relativity is that one

cannot exploit it to transmit information faster than light or

instantaneously.)

1982

300

QUANTUM MECHANICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-300-320.jpg)

![Quantum Fluctuation

In quantum physics, a quantum vacuum fluctuation (or quantum fluctuation or vacuum

fluctuation) is the temporary change in the amount of energy in a point in space,[1]

arising

from Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.

According to one formulation of the principle, energy and time can be related by the relation

That means that conservation of energy can appear to be violated, but only for small times.

This allows the creation of particle-antiparticle pairs of virtual particles. The effects of

these particles are measurable, for example, in the effective charge of the electron,

different from its "naked" charge.

SOLO

315

QUANTUM MECHANICS

Quantum theory is different from classical theory. The difference is in accounting for the

inner workings of subatomic processes. Classical physics cannot account for such. It was

pointed out by Heisenberg that what "actually" or "really" occurs inside such subatomic

processes as collisions is not directly observable and no unique and physically definite

visualization is available for it. Quantum mechanics has the specific merit of by-passing

speculation about such inner workings. It restricts itself to what is actually observable and

detectable. Virtual particles are conceptual devices that in a sense try to by-pass

Heisenberg's insight, by offering putative or virtual explanatory visualizations for the

inner workings of subatomic processes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-315-320.jpg)

![Quantum Foam

Quantum foam (also referred to as space time foam) is a concept in quantum mechanics devised by John

Wheeler in 1955. The foam is supposed to be conceptualized as the foundation of the fabric of the

universe.[1]

Additionally, quantum foam can be used as a qualitative description of subatomic space time turbulence

at extremely small distances (on the order of the Planck length). At such small scales of time and space,

the Heisenberg uncertainty principle allows energy to briefly decay into particles and antiparticles and

then annihilate without violating physical conservation laws. As the scale of time and space being

discussed shrinks, the energy of the virtual particles increases. According to Einstein's theory of general

relativity, energy curves space time. This suggests that—at sufficiently small scales—the energy of these

fluctuations would be large enough to cause significant departures from the smooth space time seen at

larger scales, giving space time a "foamy" character

Quantum foam is theorized to be the 'fabric' of the Universe, but however cannot be observed yet

because it is just too small. Also, quantum foam is theorized to be created by virtual particles of very

high energy. Virtual particles appear in quantum field theory, arising briefly and then annihilating

during particle interactions in such a way that they affect the measured outputs of the interaction,

even though the virtual particles are themselves space. These "vacuum fluctuations" affect the

properties of the vacuum, giving it a nonzero energy known as vacuum energy, itself a type of zero-

point energy. However, physicists are uncertain about the magnitude of this form of energy.[8]

The Casimir effect can also be understood in terms of the behavior of virtual particles in the empty

space between two parallel plates. Ordinarily, quantum field theory does not deal with virtual

particles of sufficient energy to curve spacetime significantly, so quantum foam is a speculative

extension of these concepts which imagines the consequences of such high-energy virtual particles at

very short distances and times.

SOLO

319

QUANTUM MECHANICS

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-319-320.jpg)

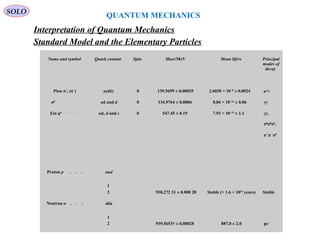

![QUANTUM MECHANICS

SOLO

Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

330

The experiments are done by performing measurements, in which quantum particles are involved.

Those quantum particles (atoms, photon, electrons, protons, neutrons, …) have energy that can be

detected.

• The lest expensive measurements are those with photons (electromagnetic spectrum) that can be

performed in labs with, relatively, non expensive instruments.

• Other experiments are performed by analyzing cosmic rays.

Feynman said, the hadron-hadron work [in the Stanford Linear Acceleration Center

SLAC] was like trying to figure out a pocket watch by smashing two of them together

and watching the pieces fly out.

“Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman” by James Gleick, 1992

Cosmic rays are immensely high-energy radiation, mainly originating outside the Solar

System. They may produce showers of secondary particles that penetrate and impact the

Earth's atmosphere and sometimes even reach the surface. Composed primarily of high-

energy protons and atomic nuclei.

• The most expensive experiments (Particles Collider Facilities), where high energy

particles are smashed. The results of this process (energy scattering) are analyzed to

detect new quantum effects.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-330-320.jpg)

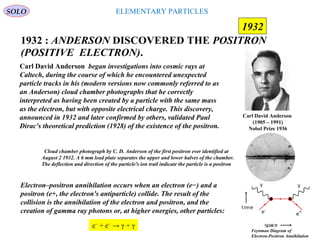

![•Quantity v

•t

•e

Symbol Value[7][8]

Relative

Standard

Uncertainty

speed of light in vacuum 299 792 458 m·s−1

defined

Newtonian constant of

gravitation

6.67384(80)×10−11

m3

·kg

−1

·s−2 1.2 × 10−4

Planck constant

6.626 069 57(29) × 10−34

J·s

4.4 × 10−8

reduced Planck constant

1.054 571 726(47) ×

10−34

J·s

4.4 × 10−8

Table of universal constants

SOLO

350](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-introductiontoquantummechanics-sololaptop-150813162751-lva1-app6891/85/5-introduction-to-quantum-mechanics-350-320.jpg)

![Table of electromagnetic constants

•Quantity v

•t

•e

Symbol Value[7][8]

(SI units)

Relative Standard

Uncertainty

magnetic constant

(vacuum permeability)

4π × 10−7

N·A−2

= 1.256 637 061... ×

10−6

N·A−2 defined

electric constant (vacuum

permittivity)

8.854 187 817... × 10−12

F·m−1

defined

characteristic impedance

of vacuum

376.730 313 461... Ω defined

Coulomb's constant 8.987 551 787... × 109

N·m²·C−2

defined

elementary charge 1.602 176 565(35) × 10−19

C 2.2 × 10−8

Bohr magneton 9.274 009 68(20) × 10−24

J·T−1

2.2 × 10−8

conductance quantum 7.748 091 7346(25) × 10−5

S 3.2 × 10−10

inverse conductance

quantum

12 906.403 7217(42) Ω 3.2 × 10−10

Josephson constant 4.835 978 70(11) × 1014

Hz·V−1

2.2 × 10−8

magnetic flux quantum 2.067 833 758(46) × 10−15

Wb 2.2 × 10−8

nuclear magneton 5.050 783 53(11) × 10−27

J·T−1

2.2 × 10−8

von Klitzing constant 25 812.807 4434(84) Ω 3.2 × 10−10

SOLO