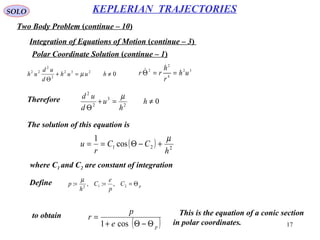

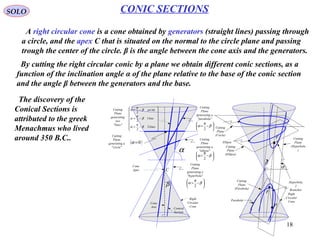

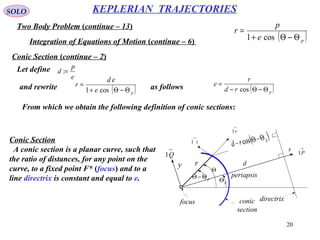

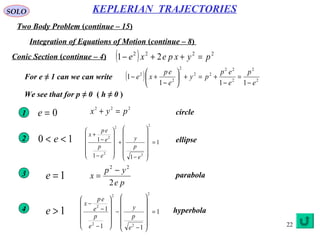

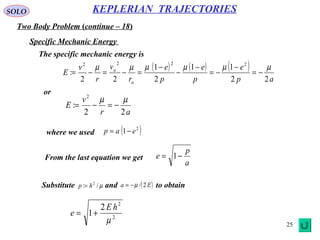

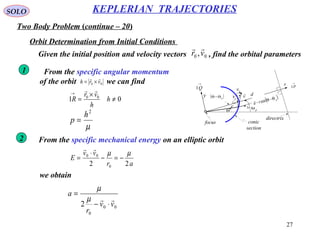

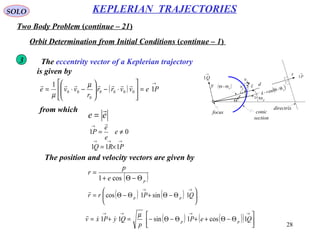

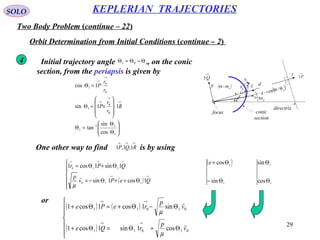

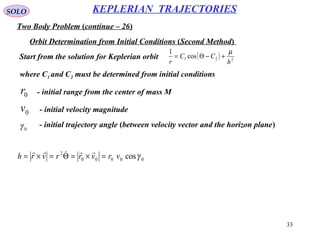

The document discusses Kepler's laws of planetary motion and Newton's laws of motion and universal gravitation, providing insights on the two-body problem and its mathematical implications. It elaborates on various concepts including conservation of angular momentum, mechanical energy, and the integration of equations of motion relevant to orbital trajectories. The document serves as a comprehensive guide to understanding the dynamics of celestial bodies and their orbits.

![14

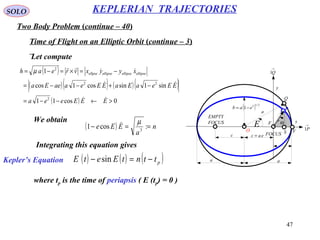

SOLO

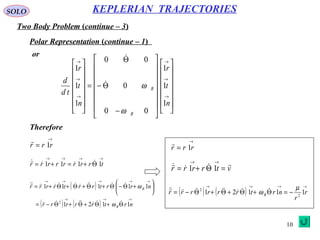

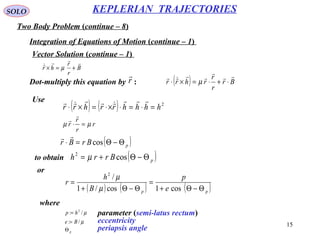

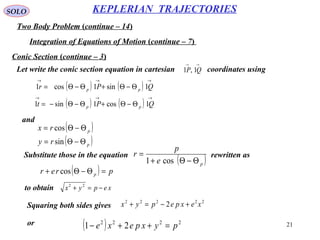

Two Body Problem (continue – 7)

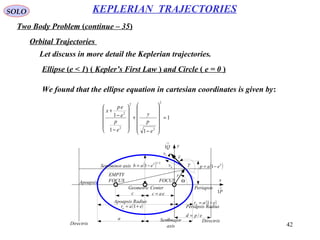

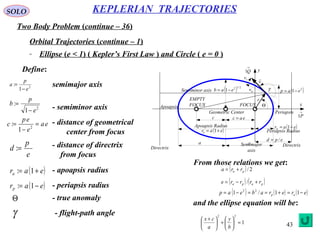

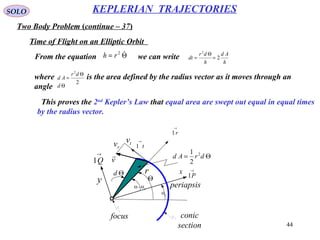

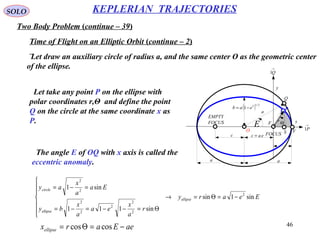

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Integration of Equations of Motion

Vector Solution

Cross-multiply the equation of motion with the specific angular momentum

→

−= r

r

r 12

µ

h

hr

r

hr

×−=× 3

µ

( ) ( ) ( )rr

td

d

rhrh

td

d

rhrhr

td

d

××+×=×+×=×

The left side is

( ) ( ) hrr

r

rrhrrrrrrrhr

×=

−××+×=××+××+×=

0

3

0

µ

The right side can be written

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )

=−=−=⋅−⋅=××−=×−

r

r

td

d

r

r

r

v

r

rrrrv

r

vrrrrv

r

vrr

r

hr

r

µ

µµµµµµ

2

2

3333

Equaling both sides gives ( )

=×

r

r

td

d

hr

td

d

µ

Integrating both sides B

r

r

hr

+=× µ

where is the constant of integrationB

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-14-320.jpg)

![23

SOLO

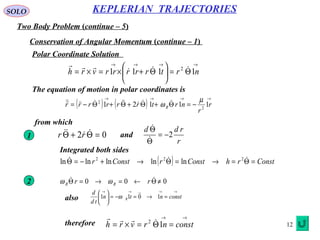

Two Body Problem (continue – 16)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

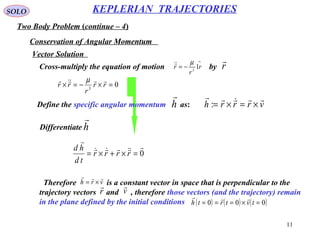

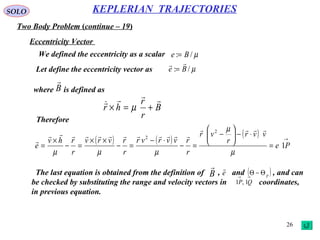

Velocity on the Trajectory

Let find the velocity on the trajectory in and coordinates

→→

tr 1,1

→→

QP 1,1

→→→→

+=Θ+== QyPxtrrrrv 1111

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]

→→

Θ−ΘΘ+Θ−Θ+Θ−ΘΘ−Θ−Θ= QrrPrr pppp 1cossin1sincos

From the equation of motion

( )pe

p

r

Θ−Θ+

=

cos1 hr =Θ2 µ/: 2

hp =

we obtain ( )

( )[ ]

( )

( )p

p

p

p

r

e

p

p

eh

r

h

e

ep

td

d

d

dr

rv

Θ−Θ=

Θ−Θ

=

Θ−Θ+

Θ−Θ

=

Θ

Θ

==

sin

sin

cos1

sin

22

µ

( )[ ]pt e

pr

p

r

h

rrv Θ−Θ+===Θ= cos12

µµ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-23-320.jpg)

![24

SOLO

Two Body Problem (continue – 17)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Velocity on the Trajectory (continue – 1)

Let substitute those results in the velocity equation to obtain the components

in coordinates.

→→

QP 1,1

( ) ( )[ ]

→→→→

Θ−Θ++Θ−Θ−=+= Qe

p

P

p

QyPxv pp 1cos1sin11

µµ

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]{ } 2/12222/1222/122

cos1sin pptr ee

p

yxvvv Θ−Θ++Θ−Θ=+=+=

µ

( )[ ] 2/12

cos21 pee

p

v Θ−Θ++=

µ

Θ

pΘ

pΘ−Θ

r d

directrix

focus conic

section

x

y

→

P1

→

Q1

→

r1

→

t1

v

rv tv

periapsis

The velocities at the periapsis

and apoapsis are

( )pΘ=Θ

( )π+Θ=Θ p

( )e

p

va −= 1

µ

( )e

p

vp += 1

µ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-24-320.jpg)

![30

SOLO

Two Body Problem (continue – 23)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Orbit Determination from Initial Conditions (continue – 3)

Θ pΘr

d

directrix

focus conic

section

x

y

→

P1

→

Q1

→

r1

→

t1

v

rv

tv( )pΘ−Θ γ

Using

1

0

cos1 Θ+

=

e

p

r

we finally obtain

( )

Θ+

Θ

=

Θ−

Θ+

=

→→

→→

01

0

0

1

01

0

0

1

cos

sin

1

sin

cos

1

v

p

r

r

p

Q

v

p

r

r

p

e

P

µ

µ

( )[ ] ( )

( )[ ] ( )

( )[ ] ( ) 01

0

01

01

0

01

011

0

011

sincos11

sincos1cos1

sincoscossinsinsincoscos

1sin1cos

v

p

rr

r

p

r

v

p

rr

re

p

r

v

p

rr

re

p

r

QPrr

Θ−Θ+

Θ−Θ+−=

Θ−Θ+Θ−Θ+−Θ+=

ΘΘ−ΘΘ+ΘΘ+Θ+Θ=

Θ+Θ=

→

→

→

→→

µ

µ

µ

Therefore](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-30-320.jpg)

![31

SOLO

Two Body Problem (continue – 24)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Orbit Determination from Initial Conditions (continue – 4)

Θ pΘr

d

directrix

focus conic

section

x

y

→

P1

→

Q1

→

r1

→

t1

v

rv

tv( )pΘ−Θ γ

where we used

( )

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )[ ] 011

0

0

11

011

0

0

11

coscos

sinsinsin

coscossinsin

sincoscossin

1cos1sin

ve

p

r

r

p

ee

p

ve

p

r

r

p

ee

p

QeP

p

v

Θ+Θ+Θ+

Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ

=

ΘΘ++ΘΘ+

ΘΘ+−Θ+Θ

−=

Θ++Θ−=

→

→

→→

µ

µ

µ

( ) ( )[ ] ( )

( )[ ]

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] 01

0

01

0

1

0

00

01

0

0

1111

011

0

0

111111

cos11sin

1

cos1

cos11

cos1sincos1sin

cos1cos1

sinsincoscossinsin

v

p

r

r

pr

e

pr

vr

v

p

r

r

p

eee

p

ve

p

r

r

p

ee

p

Θ+Θ−−+

Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ−

⋅

=

Θ+Θ−−+

Θ+Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ

=

Θ++Θ+Θ+−+

Θ−Θ−Θ−ΘΘ+Θ−ΘΘ−Θ

=

→

→

→

→

µ

µ

µ

( )

10

1111000

sin

1cos1sin1sin1cos

Θ=

Θ++Θ−⋅

Θ+Θ=⋅

→→→→

e

p

r

QeP

p

QPrvr

µ

µ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-31-320.jpg)

![32

SOLO

Two Body Problem (continue – 25)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Orbit Determination from Initial Conditions (continue – 5)

Θ pΘr

d

directrix

focus conic

section

x

y

→

P1

→

Q1

→

r1

→

t1

v

rv

tv( )pΘ−Θ γ

Summarize

( )[ ] ( ) 01

0

01 sincos11 v

p

rr

r

p

r

r

Θ−Θ+

Θ−Θ+−=

→

µ

( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] 01

0

01

0

1

0

00

cos11sin

1

cos1 v

p

r

r

pr

e

pr

vr

v

Θ+Θ−−+

Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ−

⋅

=

→

→

µ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-32-320.jpg)

![35

SOLO

Two Body Problem (continue – 28)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Orbit Determination from Initial Conditions (Second Method - 2)

We have

( )

0

2

00

201

cos

11

cos

γλ rr

CC −=−Θ

( ) 0

0

201 tan

1

sin γ

r

CC =−Θ

( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

0

2

0

00

0

0

0

2

00

0

2

0

02010201

0

2

0

2001

cos

1

sintan

1

cos

cos

11

cos

1

sinsincoscos

cos

1

cos

1

γλ

γ

γλ

γλ

γλ

rrrr

r

CCCC

r

CC

r

+Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ

−=

+Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ=

+−Θ+Θ−Θ=

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

0

00

0

2

0

0

0000

0

2

00

cos

cos

cos

cos1

cos

sinsincoscos

cos

cos1

γ

γ

γλ

γ

γγ

γλ

+Θ−Θ

+

Θ−Θ−

=

Θ−Θ−Θ−Θ

+

Θ−Θ−

=

r

r

which, when developed further, gives](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-35-320.jpg)

![37

SOLO

Two Body Problem (continue – 30)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Orbit Determination from Initial Conditions (Second Method - 3)

( ) ( )0000

0

2

0

coscoscos1

cos

γγλ

γλ

+Θ−Θ+Θ−Θ−

=

r

r

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( )2

0

2

0

2

0

22

00

2

0002

0

2

0

2

0

22

00

2

000

0000

1coscossin

cos1cossincossin

1coscossin1

cos1cossincossin1

coscoscos1

−+

Θ−Θ−+Θ−Θ−

−++=

Θ−Θ−+Θ−Θ−=

+Θ−Θ+Θ−Θ−

γλγγλ

γλγγλ

γλγγλ

γλγγλ

γγλ

The denominator can be expressed as

0

2

0 cos: γλrp =

( ) ( ) 1cos21cos2cos1coscossin: 0

2

0

2

0

222

0

2

0

2

0

22

+−=+−=−+= γλλγλγλγλγγλe

We define

−

=Θ−Θ −

1cos

cossin

tan:

0

2

001

0

γλ

γγλ

p

( ) ( )

( ) ( )[ ] ( )pp

ee Θ−Θ+=Θ−Θ+Θ−Θ+=

+Θ−Θ+Θ−Θ−

cos1cos1

coscoscos1

00

0000

γγλto obtain](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-37-320.jpg)

![38

SOLO

Two Body Problem (continue – 31)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Orbit Determination from Initial Conditions (Second Method - 4)

( ) ( )0000

0

2

0

coscoscos1

cos

γγλ

γλ

+Θ−Θ+Θ−Θ−

=

r

r

The denominator can be expressed as

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )pp

ee Θ−Θ+=Θ−Θ+Θ−Θ+=+Θ−Θ+Θ−Θ− cos1cos1coscoscos1 000000

γγλ

We obtain again the fact that the trajectory is a conic section given by

( )pe

p

r

Θ−Θ+

=

cos1

We can also write

( )[ ] λγλλ

γλ

−

=

+−−

=

−

=

21cos21

cos

1

: 0

0

2

0

2

0

2

rr

e

p

a

and

0

2

0 cos: γλrp = ( ) 1cos2: 0

2

+−= γλλe](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-38-320.jpg)

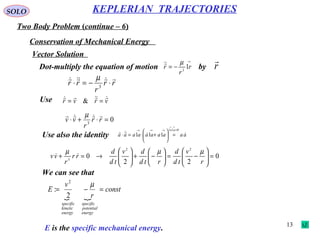

![48

SOLO

Two Body Problem (continue – 41)

KEPLERIAN TRAJECTORIES

Time of Flight on an Elliptic Orbit (continue – 4)

From

x

y

eac =

a a

( ) 2/12

1 eab −=

rΘ

FOCUS

EMPTY

FOCUS

c

→

P1

→

Q1

a

F

Q

O VS

E

P

Eeary

aeEarx

ellipse

ellipse

sin1sin

coscos

2

−=Θ=

−=Θ=

we have

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]

( )Eea

EeEeaEeaaeEar

cos1

coscos21sin1cos

2/1222/12222

−=

+−=−+−=

Therefore

Θ+

Θ−

=

−

−

=Θ

Θ+

Θ+

=

−

−

=Θ

cos1

sin1

sin

cos1

sin1

sin

cos1

cos

cos

cos1

cos

cos

22

e

e

E

Ee

Ee

e

e

E

Ee

eE

( )( )

Ee

Ee

Ee

eEEe

sin1

cos11

sin1

coscos1

sin

cos1

2

tan

22

−

−+

=

−

+−−

=

Θ

Θ−

=

Θ

From

2

tan

1

1

2

tan

E

e

e

−

+

=

Θ

or

and are always in the same quadrant.2

Θ

2

E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kepleriantrajectories-150813153625-lva1-app6891/85/Keplerian-trajectories-48-320.jpg)