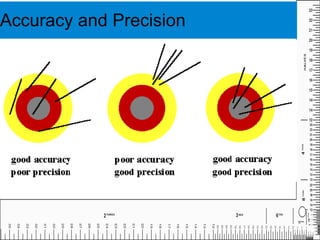

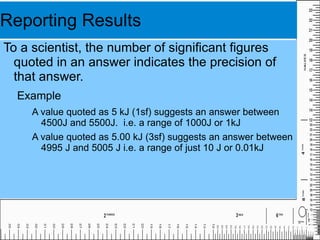

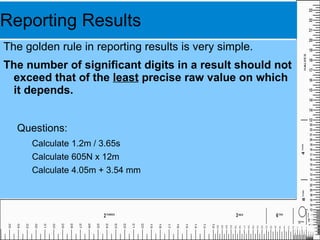

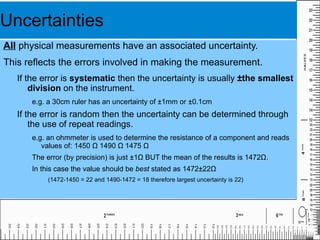

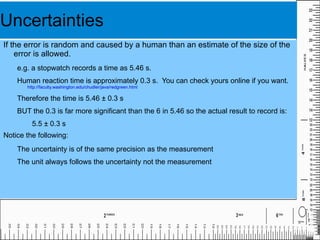

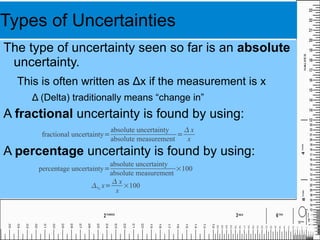

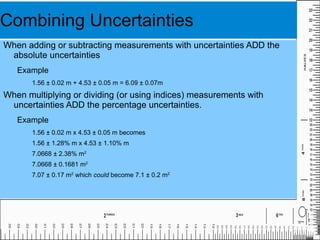

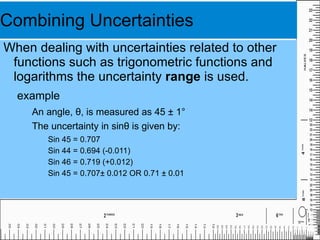

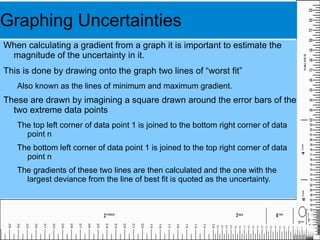

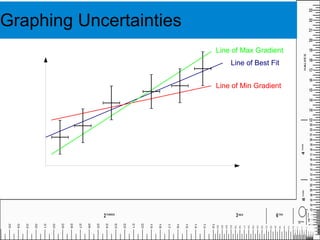

This document discusses uncertainties and errors in physical measurements. It explains that there are two types of errors - random errors which are unpredictable, and systematic errors caused by imperfect measuring equipment. Random errors can be reduced by repeating measurements, while systematic errors are reduced by calibrating equipment. Accuracy refers to how close a measurement is to the true value, while precision refers to how close repeated measurements are. The number of significant figures reported in a result should not exceed the least precise value used. The document also discusses determining and expressing uncertainties in measurements, and how to combine uncertainties when performing calculations or graphing data.