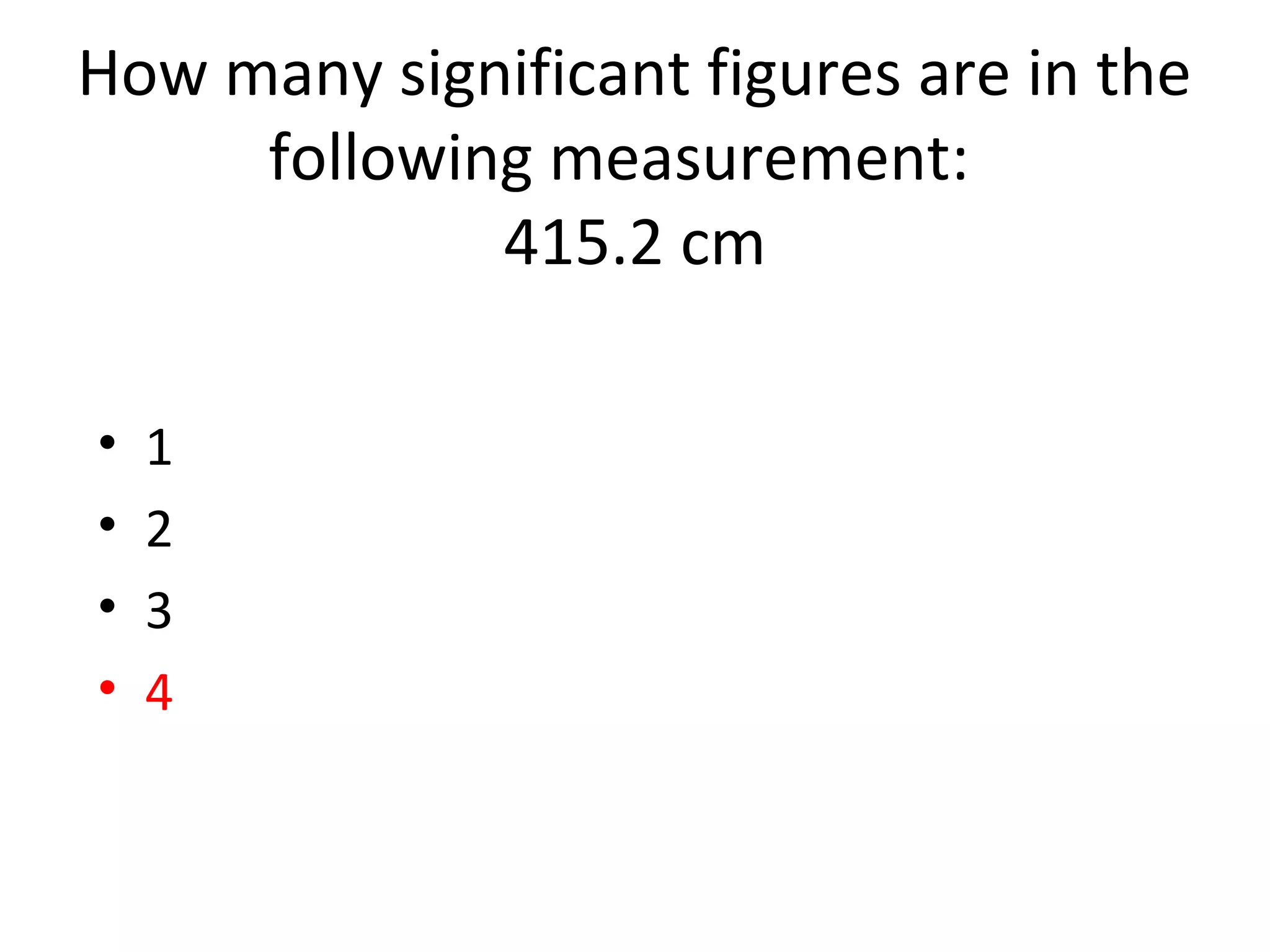

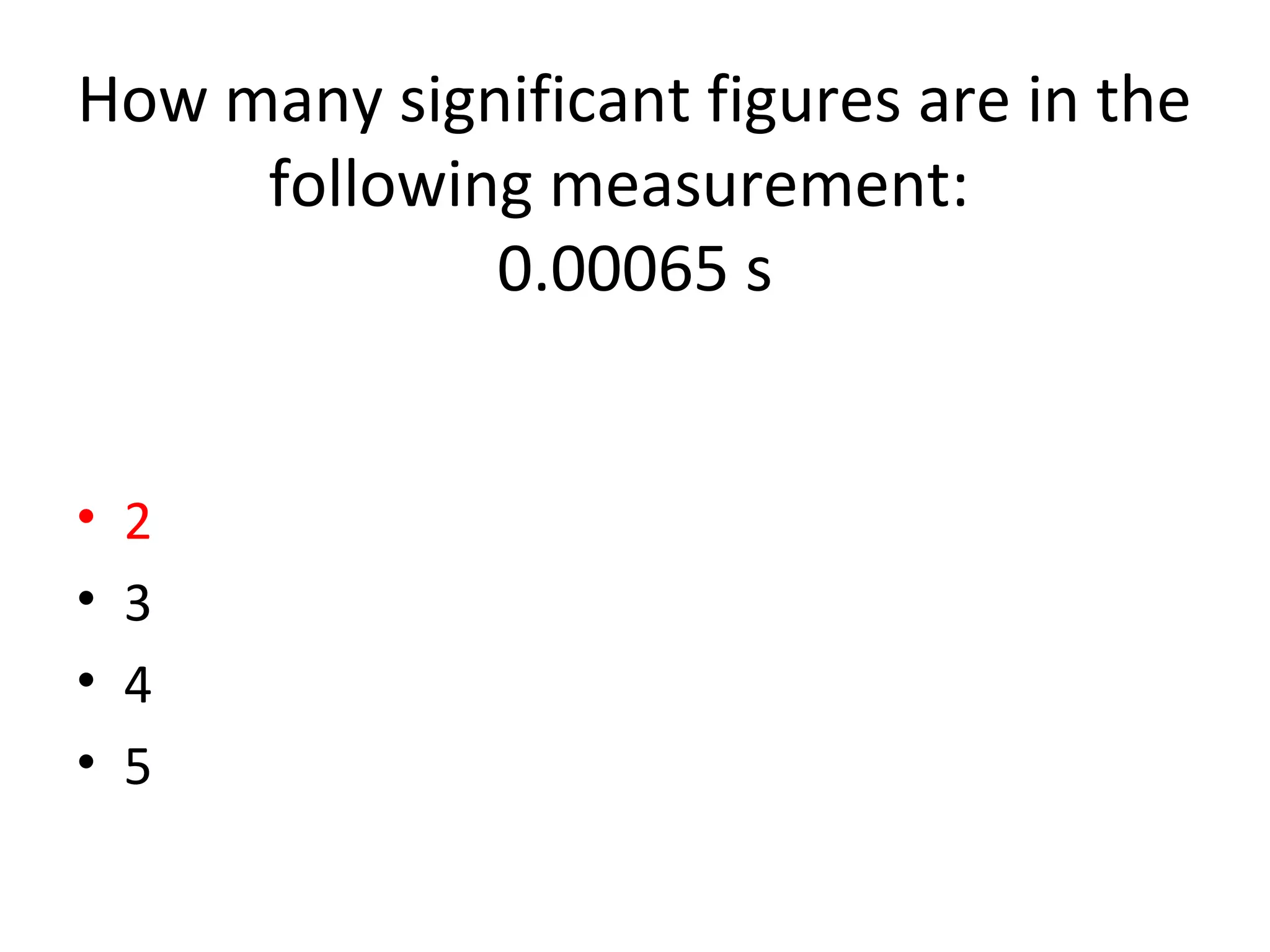

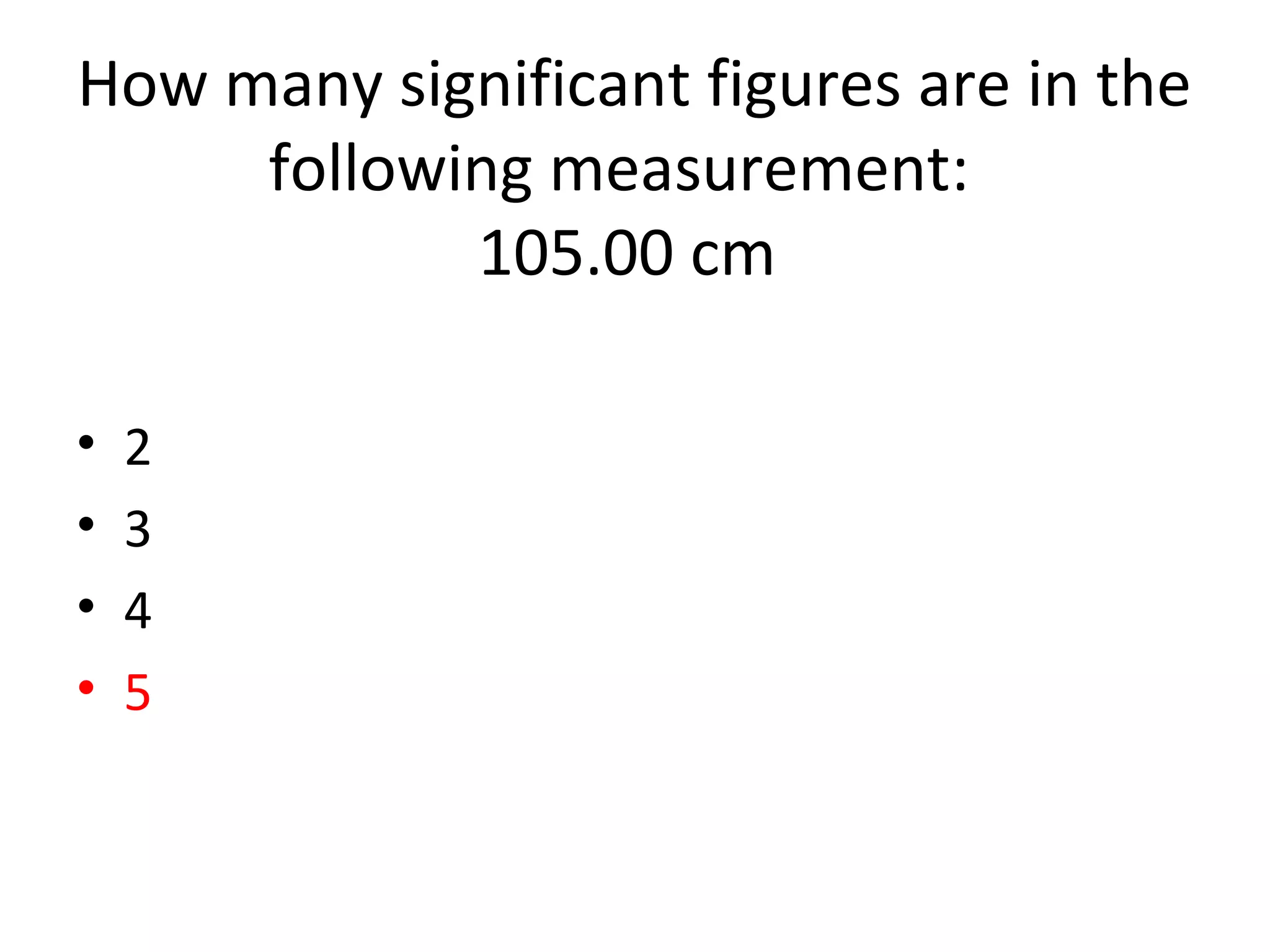

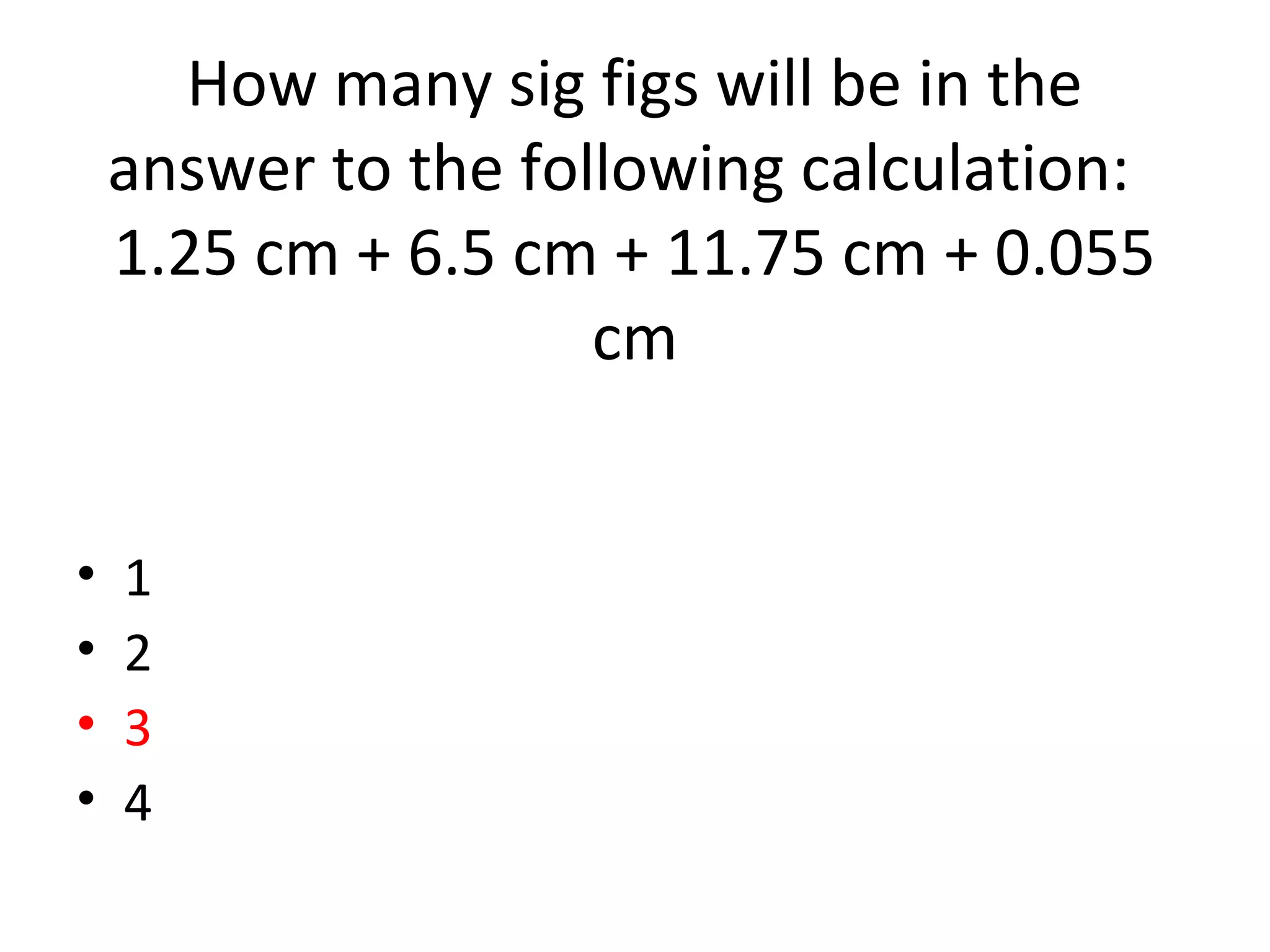

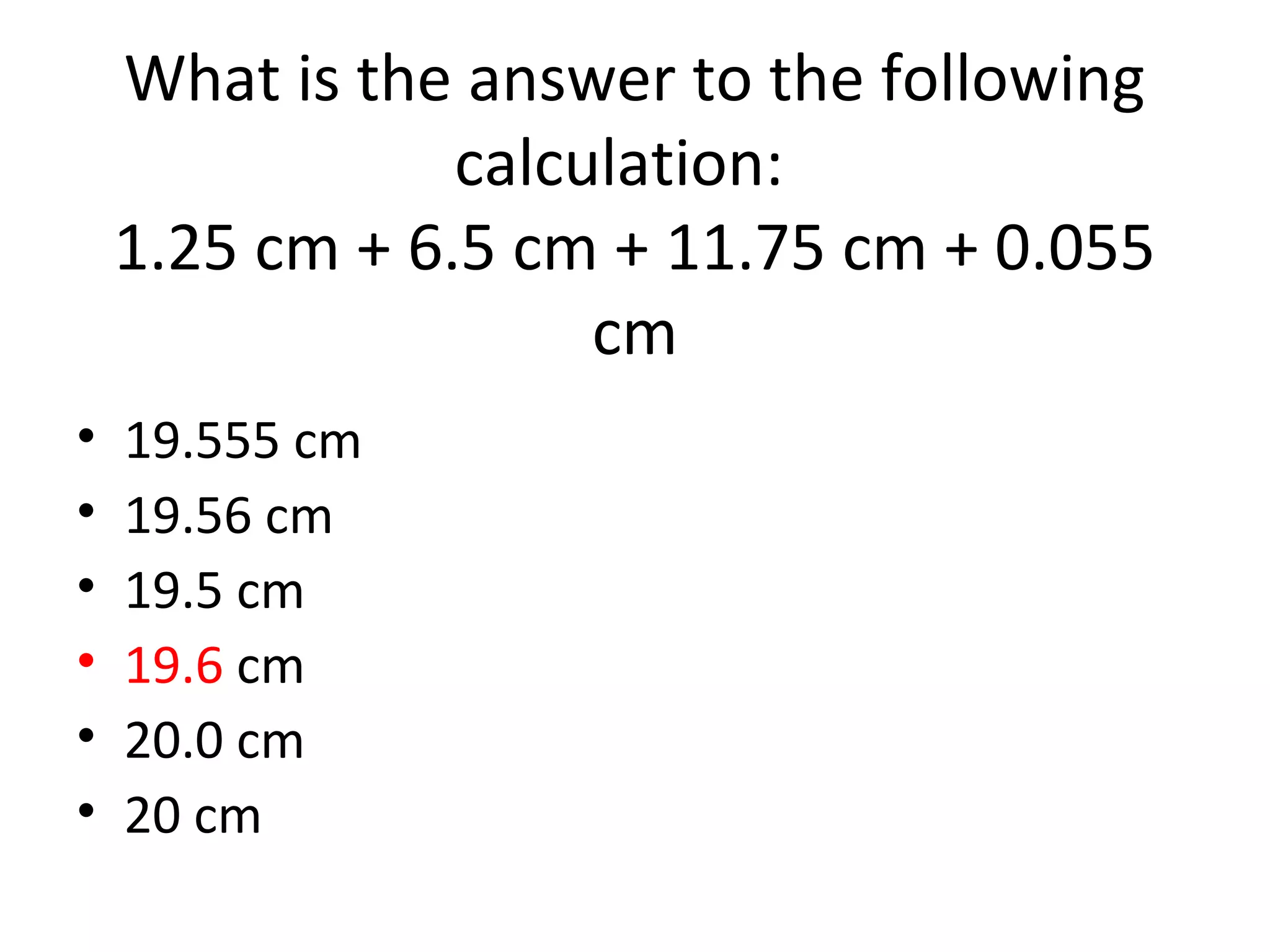

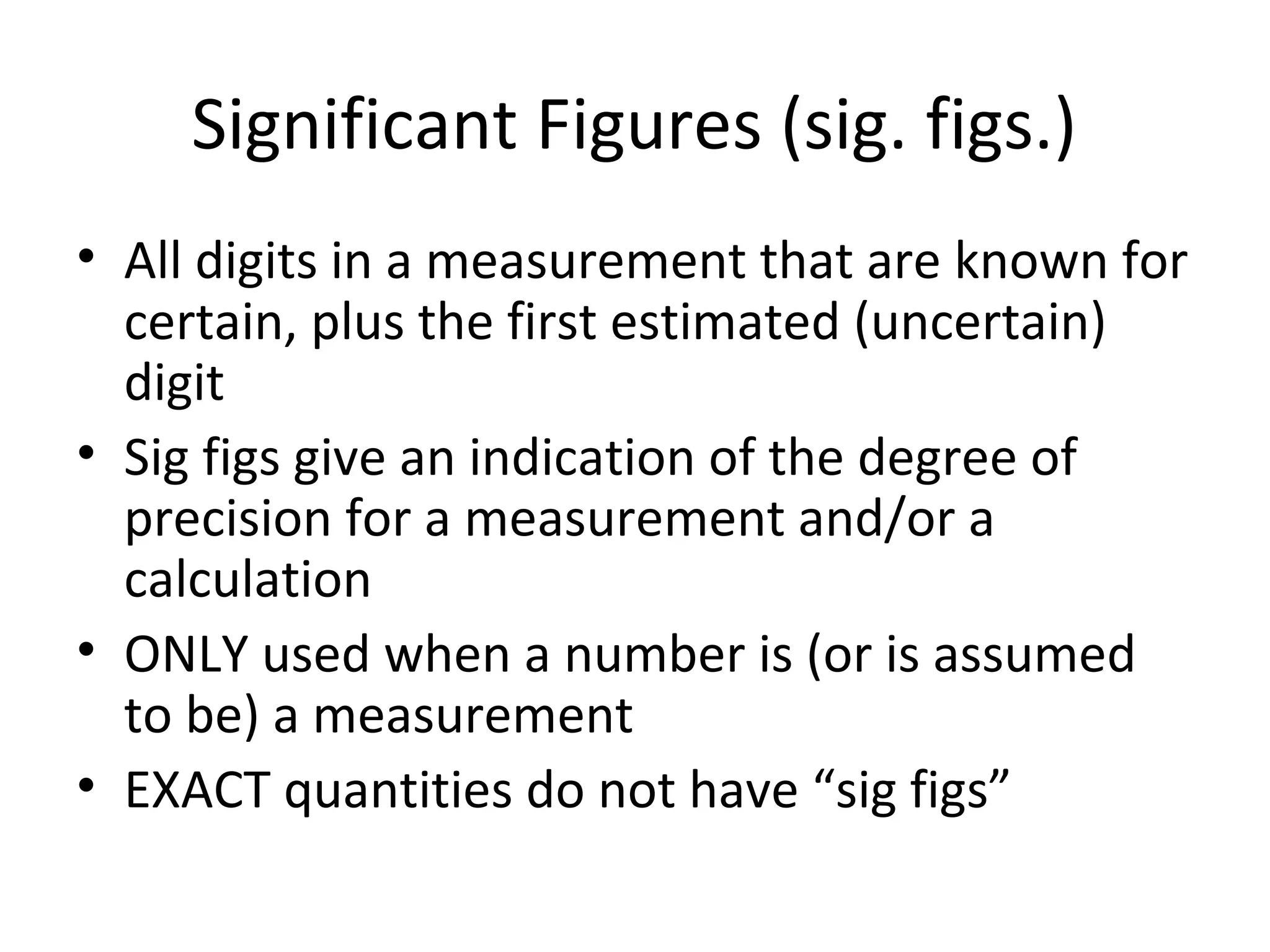

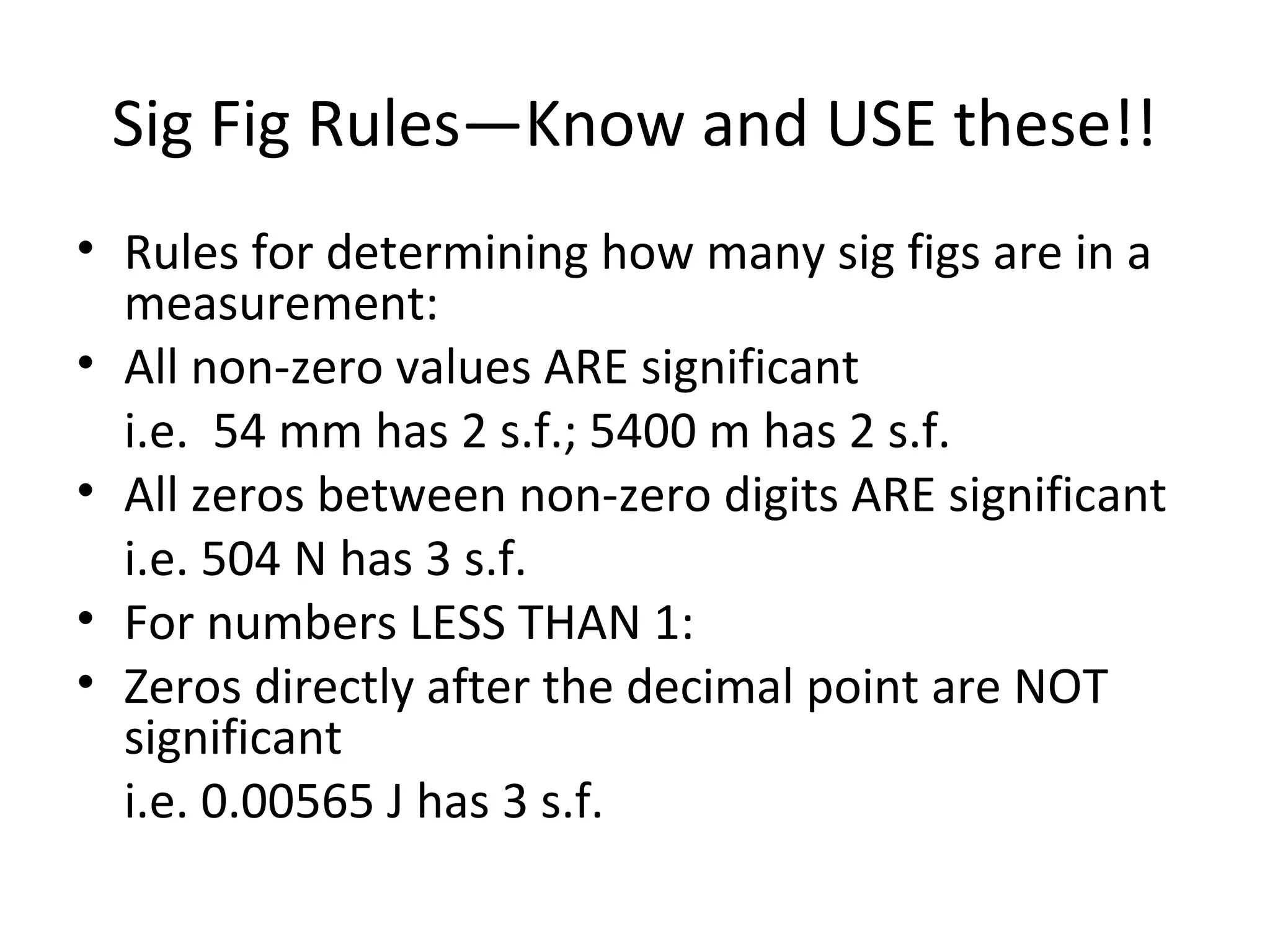

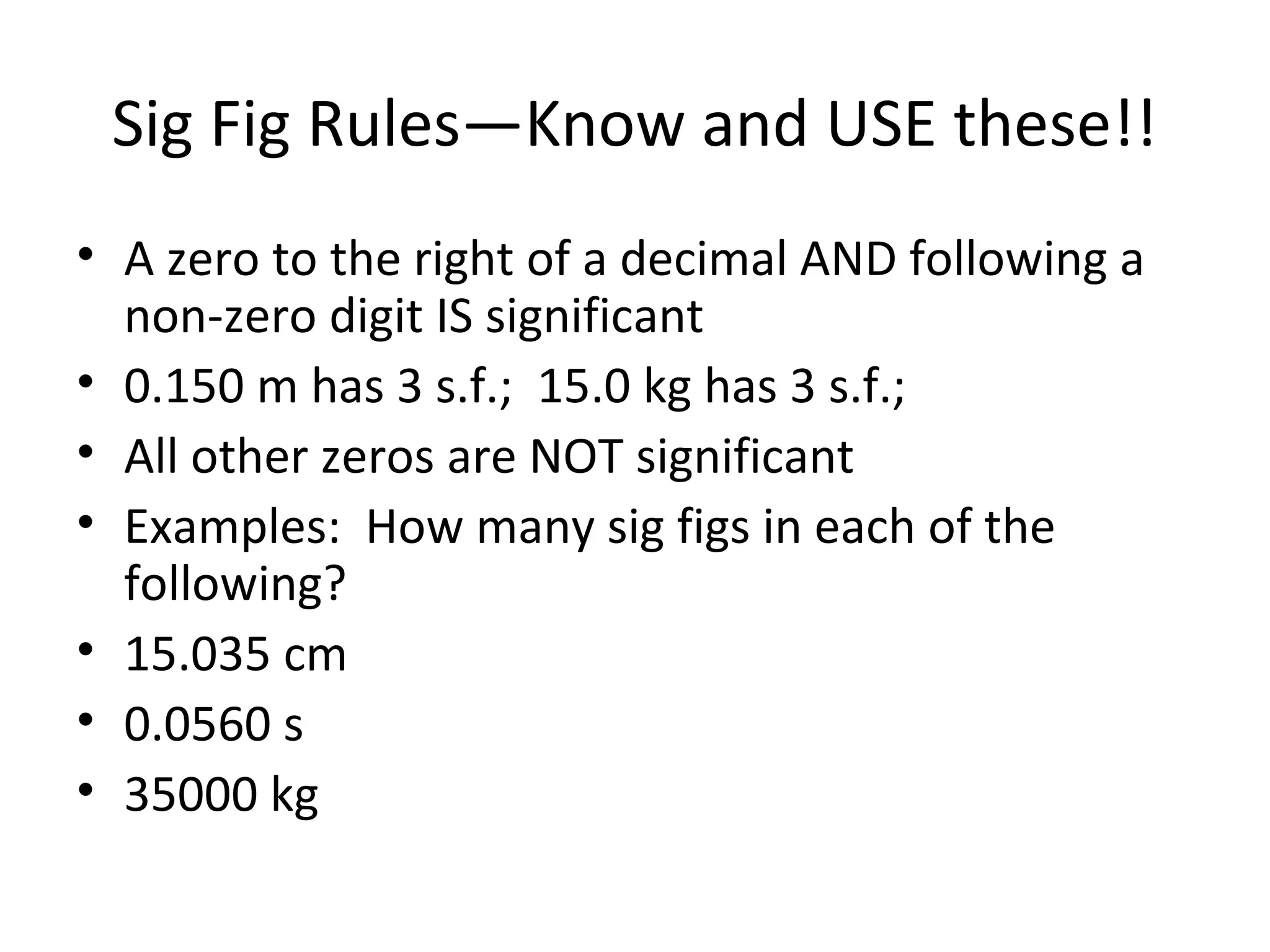

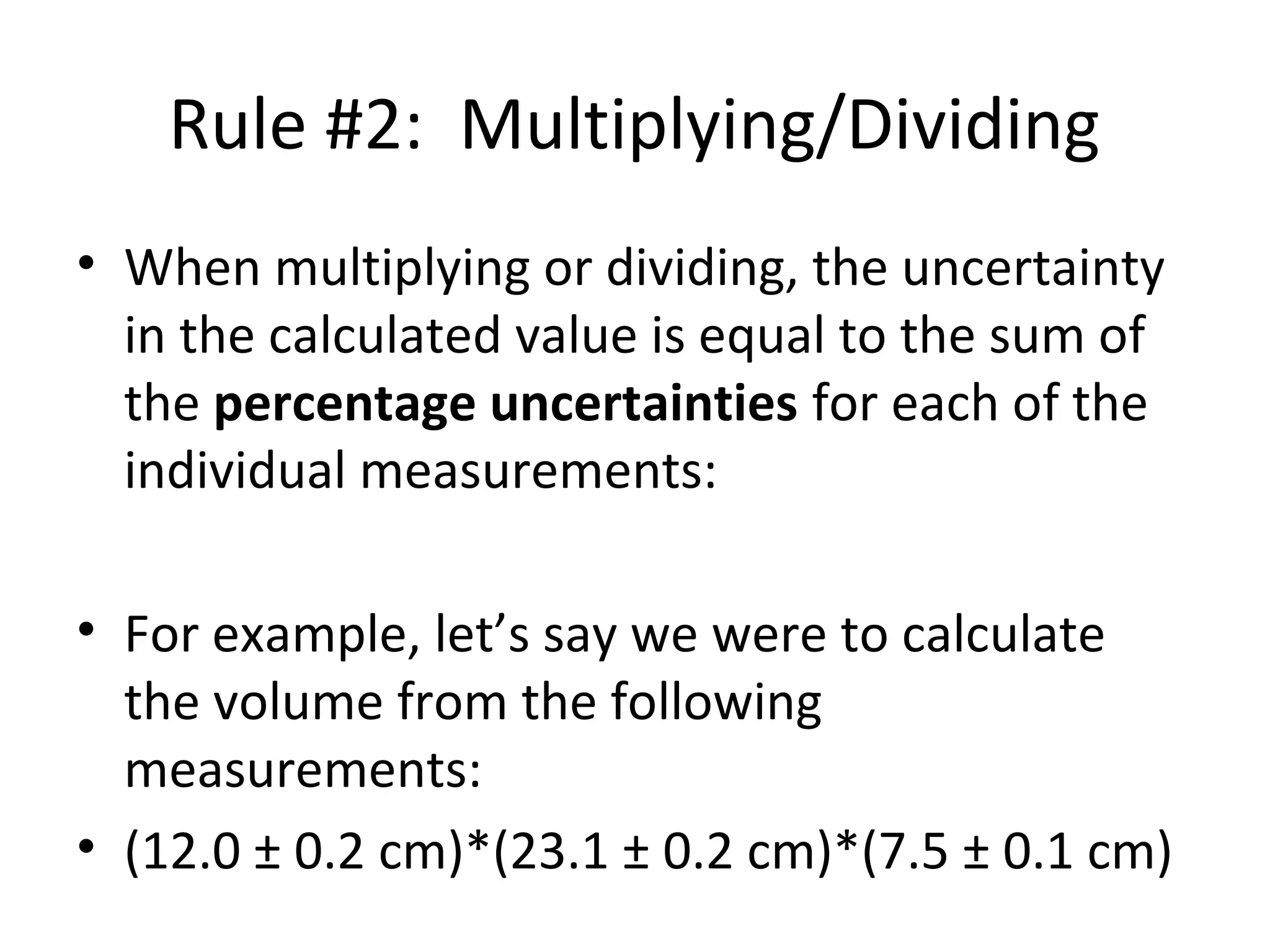

This document discusses different types of errors in experimental measurements and calculations. It describes random errors, which vary unpredictably, and systematic errors, which are consistent biases. Random errors can be reduced by taking more trials, while systematic errors must be accounted for. Mistakes are distinguished from errors. Significant figures rules for measurements and calculations are explained. The concepts of uncertainty, including limits of reading, degrees of uncertainty, absolute and relative uncertainty, and uncertainty propagation through calculations, are introduced.