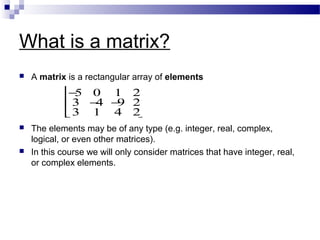

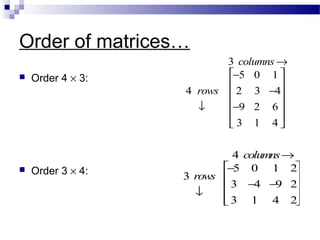

This document provides an overview of matrices and matrix operations. It defines what a matrix is and discusses matrix order and elements. It then covers basic matrix operations like scalar multiplication, addition, and multiplication. It introduces the concepts of transpose, special matrices like diagonal and triangular matrices, and the null and identity matrices. The document aims to define fundamental matrix concepts and arithmetic operations.

![…Matrix operations: transpose…

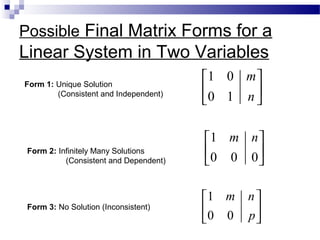

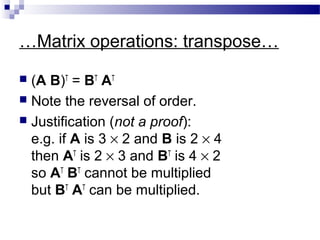

If B = AT

, then bij = aji

i.e. the transpose of an m × n matrix is an n × m matrix with the rows

and columns swapped.

e.g.

−

−−

=

−

−

−

4641

1230

3925

413

629

432

105

T

[ ]3925

3

9

2

5

−−=

−

−

T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140505135713-phpapp01/85/systems-of-linear-equations-matrices-12-320.jpg)

![Special matrices: row and column

A 1 × n matrix is called a row matrix.

e.g.

An m × 1 matrix is called a column matrix.

e.g.

1 columns→

3 rows

↓

3

−1

5

6 columns→

1 rows

↓

2 1 1 −2 1 −5[ ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140505135713-phpapp01/85/systems-of-linear-equations-matrices-14-320.jpg)

![Special matrices: square

An n × n matrix is called a square matrix.

i.e. a square matrix has the same number

of rows and columns.

e.g.

[ ]

−−

−−

−−

−

4705

7350

0523

5031

211

010

210

21

32

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140505135713-phpapp01/85/systems-of-linear-equations-matrices-15-320.jpg)

![Special matrices: diagonal

A square matrix is diagonal if non-zero elements only occur on the leading diagonal.

i.e. aij = 0 for i ≠ j

e.g.

Premultiplying a matrix by a diagonal matrix scales each row by the diagonal

element.

Postmultiplying a matrix by a diagonal matrix scales each column by the diagonal

element.

[ ]

−

4000

0300

0020

0001

200

010

000

20

02

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140505135713-phpapp01/85/systems-of-linear-equations-matrices-16-320.jpg)

![Special matrices: null

The null matrix, 0, behaves like 0 in arithmetic addition

and subtraction.

Null matrices can be of any order and have all of their

elements zero.

[ ]

[ ]

=

=

=

=

0000

0000

0000

0000

00

00

00

00

00

000

0

00

0

0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140505135713-phpapp01/85/systems-of-linear-equations-matrices-18-320.jpg)

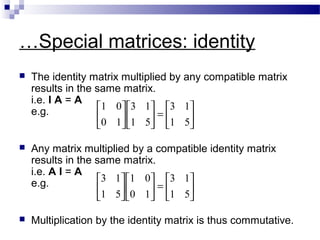

![Special matrices: identity…

The identity matrix, I, behaves like 1 in arithmetic multiplication.

Identity matrices are diagonal. They have 1s on the diagonal and 0s

elsewhere.

e.g.

In the world of the matrix the identity truly is ‘the one’.

[ ]

=

=

==

1000

0100

0010

0001

100

010

001

10

01

1

II

II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140505135713-phpapp01/85/systems-of-linear-equations-matrices-19-320.jpg)