The document provides information about matrices, including:

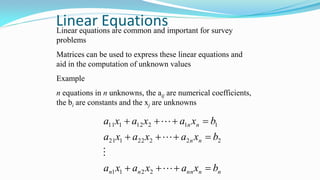

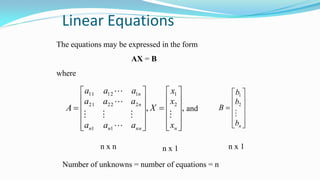

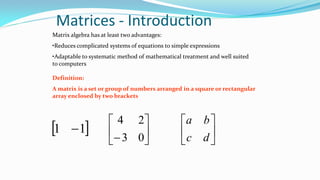

1) Matrices can reduce complex systems of equations to simple expressions and are well-suited to computers.

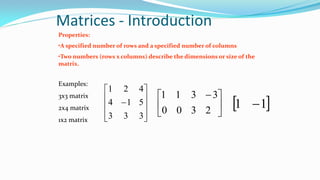

2) A matrix is a set of numbers arranged in rows and columns, with specified dimensions.

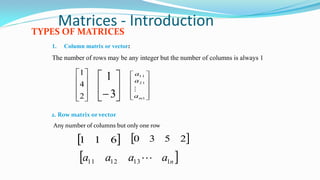

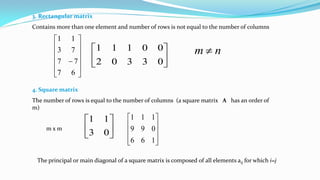

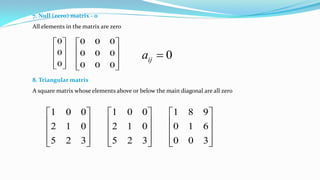

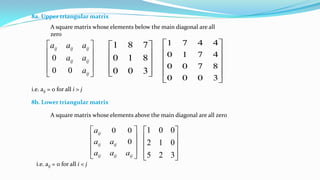

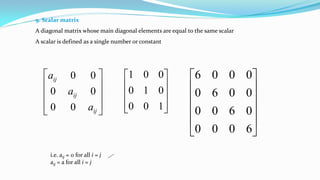

3) There are several types of matrices including column/row vectors, rectangular, square, diagonal, identity, null, triangular, and scalar matrices.

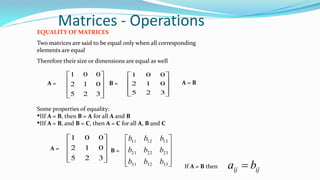

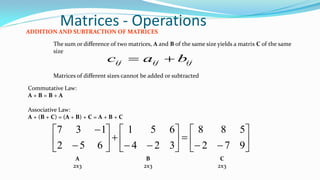

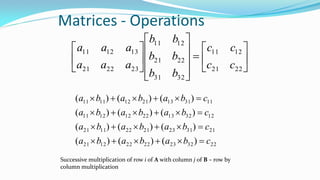

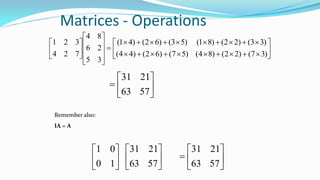

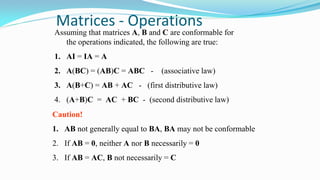

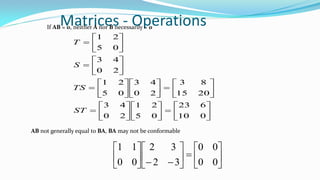

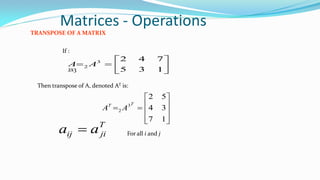

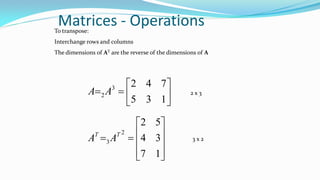

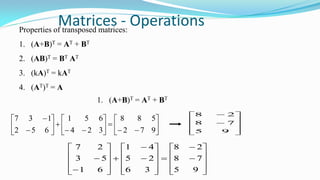

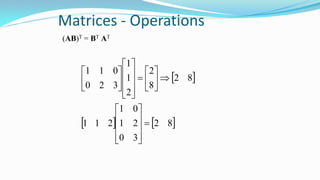

4) Matrix operations include addition, subtraction, and multiplication according to specific rules like the distributive property. Not all matrices can be multiplied together.

![Matrices - Introduction

A matrix is denoted by a bold capital letter and the elements within the matrix

are denoted by lower case letters

e.g. matrix [A] with elements aij

mnijmm

nij

inij

aaaa

aaaa

aaaa

21

22221

1211

...

...

i goes from 1 to m

j goes from 1 to n

Amxn=

mAn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/r-181005115505/85/R-Ganesh-Kumar-30-320.jpg)