This document is an issue of MAGNETOM Flash magazine focused on MR angiography. It discusses several techniques for non-contrast MR angiography including flow-sensitive dephasing prepared 3D balanced steady-state free precession. This technique uses a flow-sensitive dephasing module to selectively depict arterial flow on subtraction of images acquired during systole and diastole. The document provides details on the principles, technical considerations including choice of gradients and flow sensitization strength, and clinical applications for imaging the lower legs, feet and hands. It demonstrates comparable diagnostic accuracy to contrast-enhanced MRA for evaluation of vascular disease.

![Technology MR Angiography MR Angiography Technology

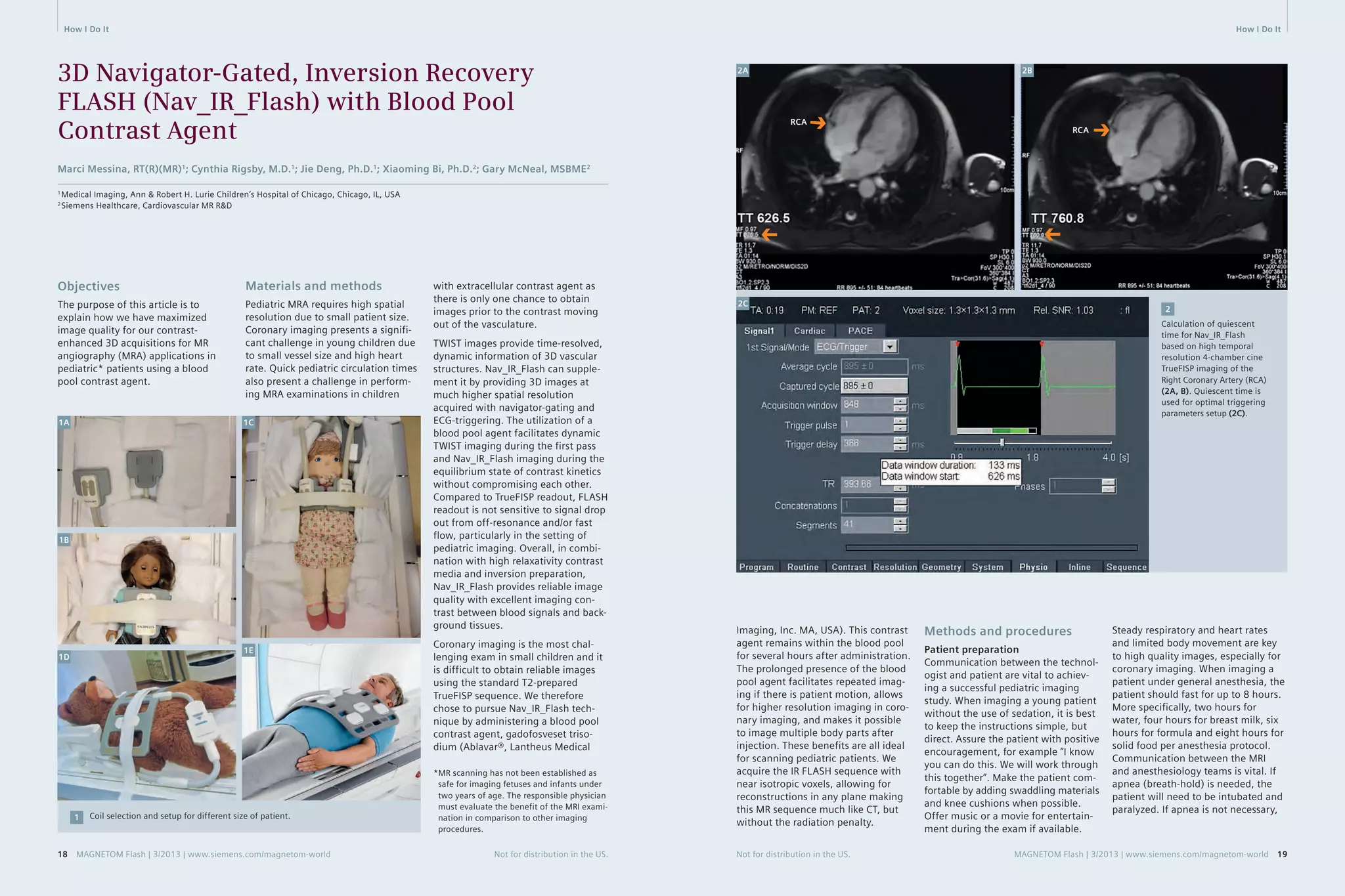

90°x 180°y 90°-x

δ

2

τ

G S

Sequence diagrams of the unipolar- (2A) and

bipolar-gradient (2B) FSD modules and their

corresponding NC-MRA images (2C, 2D). Both

modules consist of a 90°x-180°y-90°-x RF series

and two symmetric FSD gradient pulses placed

at either side of the center 180°-pulse. Notice

the stripe artifacts shown on the unipolar-gradient

FSD images interfere with the visual-ization

of main arterial branches to some

degree, which are removed by the bipolar-gradient

FSD module.

module can introduce a spatial signal

modulation in static tissues, as shown

below, if the center 180° RF pulse

frequency

response is spatially

inhomogeneous.

Mz =(–cos Θ sin2 Ф + cos2 Ф) × M0 [1]

Ф(r) = γ × r × A [2]

Where Mz is the longitudinal magneti-zation

right after FSD-preparation,

M0 is the equilibrium magnetization,

Θ is the actual flip angle of the

180°-

pulse, Ф is the phase the static

spins accumulate during the FSD gra-dient

before the 180°-pulse, which is

dependent of the gradient’s net area

A, r is the spatial variable along the

gradient direction, and γ is the gyro-magnetic

ratio. The period, λ, of the

spatial signal modulation is defined as:

λ = [3]

A simple solution to circumventing

the issue is to have Ф, or A, equal

to zero. A bipolar-gradient scheme

(Fig. 2B) becomes a natural choice

to achieve this goal. Example images

using the two gradient waveforms

are shown in figures 2C and D.

Non-Contrast MR Angiography:

Flow-Sensitive Dephasing (FSD)-Prepared

3D Balanced SSFP

Zhaoyang Fan1; Rola Saouaf2; Xin Liu3; Xiaoming Bi4; Debiao Li1

1 Biomedical Imaging Research Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2 Imaging Department, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA

3 Lauterbur Research Center for Biomedical Imaging, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology of Chinese Academy of Sciences,

Shenzhen, China

4 Siemens Healthcare, MR R&D, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Bright-Artery

Image

Dark-Artery

Image

Subtraction

Artery Vein Background tissues

1A

Signal

Intensity

GRO/PE

90°x

T2prep

Fat Sat

180°y

bSSFP

90°x

S

T2prep

1C

RF

GRO/PE

bSSFP

S

FSD

Fat Sat

180°y

G G

T2prep

90°x

90°x

(1A) Schematic of the FSD-prepared balanced SSFP technique. In the bright-artery

acquisition, both arterial blood, venous blood, and other tissues are of high signal

intensity. In the dark-artery measurement, arterial blood signals are mostly suppressed

by FSD-preparation because of substantially fast flow. Thus, arterial blood signals

remain and the signals of venous blood and background tissues are essentially

cancelled out upon image subtraction.

(1B) The sequence diagram of the bright-artery acquisition (T2-prepared balanced SSFP).

(1C) The sequence diagram of the dark-artery acquisition (FSD-prepared

balanced SSFP). G = FSD gradients, S = spoiler gradients.

RF

1

Introduction

Contrast-enhanced MR angiography

(CE-MRA) has become a non-invasive

modality of choice for detecting arte-rial

disease across various vascular

regions. However, patients with renal

insufficiency who receive gadolinium-based

agents are at risk for develop-ing

a debilitating and potentially fatal

disease known as nephrogenic sys-temic

fibrosis (NSF) [1, 2]. As a result,

a substantial population in need for

angiogram will not be able to benefit

from this radiation-free, non-invasive

diagnostic tool. Furthermore, with

CE-MRA, short contrast first-pass win-dow

in arteries often limits the imag-ing

coverage and/or spatial resolution,

and venous contamination may be

present at distal run-off vessels. All

limitations above, along with added

cost of contrast agent, have triggered

a renaissance of interest in non-con-trast

MRA (NC-MRA).

Time-of-flight and phase-contrast

are two original NC-MRA techniques,

but not widely accepted for imaging

peripheral arteries, primarily due to

the limited spatial coverage (or time

inefficiency) as well as well-known

flow artifacts associated with complex

flow [3]. Recently, a group of NC-MRA

techniques, such as fast spin-echo

based fresh blood imaging (FBI) meth-ods

(also known as NATIVE SPACE

on Siemens systems) [4], quiescent

90°x 180°y 90°-x

RF

GRO

T

δ

G S

2A

2C 2D

interval single-shot (QISS) [5] or Ghost

[6], have been developed as an alter-native

to CE-MRA for peripheral MRA.

Among them, balanced steady-state

free precession (SSFP) using flow-sen-sitive

dephasing (FSD) magnetization

preparation* is a non-contrast

approach that provides several unique

features including high arterial blood

SNR and blood-tissue CNR, isotropic

sub-millimeter spatial resolution, and

flexible FSD module to suppress flow

in different directions and with differ-ent

speeds [7]. The clinical feasibili-ties

of this method have been demon-strated

in lower legs [8, 9], feet [10],

and hands [11, 12]. Given its poten-tially

broad applications and rising

research and clinical interests, this work

provides an overview of underlying

principles and technical considerations

followed by clinical research results.

* Work in progress. The product is still under

development and not commercially available

yet. Its future availability cannot be ensured.

Principles

The FSD-prepared balanced SSFP

method exploits the arterial pulsatility

and introvoxel spin dephasing effect

to selectively depict arterial flow. The

similar idea dates back to 1980s by

Wedeen et al. [13] and Meuli et al. [14].

RF

GRO

2B

In brief, two consecutive ECG-triggered

acquisitions are acquired in one scan

(Fig. 1A). The bright-artery measure-ment

is acquired with a zero-gradient-strength

FSD preparation (i.e. T2 prep-aration)

during diastole when arterial

flow is substantially slow and thus

retains high signal intensity on bal-anced

SSFP images (Fig. 1B). The dark-artery

measurement is collected dur-ing

systole exploiting the marked

velocity difference between arterial and

venous flows. An optimal FSD prepa-ration

is employed to intravoxelly

dephase the arterial blood spins while

having little effect on venous blood

and static tissues (Fig. 1C). Magnitude

subtraction of the two measurements

allows the visualization of arteries

with dramatically suppressed back-ground

and venous signals.

Technical considerations

FSD gradient waveform

The FSD pulse sequence is a

90°x-180°y-90°-x driven equilibrium

Fourier transform diffusion preparation

module, and identical field gradients

are applied symmetrically around the

180° radio-frequency (RF) pulse [15].

Analysis based on the Bloch equation

reveals that conventional unipolar-gradient

pulses (Fig. 2A) in the FSD

1B

2 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US. Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-2-2048.jpg)

![Choice of the direction

of FSD sensitivity

Intravoxel spin dephasing requires

that flowing spins have the flow com-ponents

along the direction of applied

FSD gradients. Compared to other

NC-

MRA techniques, a unique feature

with FSD preparation is the flexibility

in direction in which the signal of

flow is exclusively suppressed. FSD

gradients have been applied in all three

logic axes simultaneously in order to

impart flow sensitization to all dimen-sions

for vessel wall imaging in previ-ous

work [18-20]. Such gradient pulse

configuration essentially renders the

flow-sensitization

unidirectional,

90°x 180°y 90°-x

RF

GRO

GPE

3A

m1 m1,RO

Choice of the FSD strength

Flow sensitization imparted by the

FSD preparation is essential for the

NC-MRA technique, and its strength

can be measured by the first-order

gradient moment denoted as m1 [7].

An unnecessarily large m1 value may

entail signal contamination from

venous blood and, potentially, other

static background tissues due to the

associated diffusion effect, whereas

incomplete delineation of arterial

segments may result from an inade-quate

m1 value. Consequently, a sub-optimal

m1 tends to cause poor image

quality, overestimation of stenosis,

or false diagnosis in FSD MRA.

The optimal m1, however, is subject

and artery specific since dephasing

of flowing spins is not only dependent

on the m1 of the FSD preparation

but also on the local flow velocity

profile [7, 16]. To obtain a satisfying

MR angiogram, an empirical m1 value

derived from a pilot study can be

advantageous. A more effective and

reliable way is to first conduct an

m1-scout scan that can rapidly (within

1 min) assess a range of first-order

gradient moment values at their effec-tiveness

in blood signal suppression,

and an individually-tailored m1 is then

selected for FSD

NC-

MRA scans [17].

S

S

4 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US.

as derived from the vector sum of all

FSD gradients. In case of FSD-prepared

MRA, the signal of a coherent flow

that is perpendicular to this direction

will not be effectively nulled. Thus,

the conventional FSD module may

result in a suboptimal vessel segment

depiction on MR angiograms.

To achieve signal suppression of

multi-directional blood flow, we pro-posed

a multi-directional FSD prepar-ative

scheme. Specifically, two (or

three for three-dimensional flow)

conventional FSD preparative mod-ules

are applied in series, with bal-anced

FSD gradients applied along

the RO direction in the first module

and along the PE direction in the sec-ond

one (Fig. 3) [21]. The spoiler

gradients

applied at the end of the

preceding

FSD module ensure that

dephased flow spin components will

not be rephased in the subsequent

one. Thus, flow components along indi-vidual

directions can be suppressed

independently by their corresponding

modules. Figure 3 shows an example

whereby certain signal loss on MIP

MRA was observed at several arterial

segments when using the conven-tional

single FSD module. Such signal

defects mimicking vessel narrowing

can be markedly ameliorated by the

two-module FSD preparation.

Clinical applications

Clinical feasibility of using the FSD-based

NC-MRA technique has been

demonstrated in multiple arterial

stations,

including lower legs [8, 9],

feet [10], and hands [11, 12]. In all

of past studies, CE-MRA was used as a

comparison reference, reflecting the

fact that invasive X-ray angiography

is not commonly performed in clinical

diagnostic imaging routines.

At lower legs, Lim et al. [8] showed

that FSD-based NC-MRA is more robust

to arterial flow variations than fast

spin-echo based techniques and “can

be performed first line at 1.5T where

exogenous contrast agents are unde-sirable

or contraindicated”. In this

MR Angiography Technology

work, FSD-based MRA demonstrated

satisfactory image quality, excellent

negative predictive value (91.7%),

and good sensitivity (80.3%), specific-ity

(81.7%), and diagnostic accuracy

(81.3%) for hemodynamically signifi-cant

(≥ 50%) stenosis. Another study

by Liu et al. [9] showed that the num-ber

of diagnostic segments is not sig-nificantly

between FSD-based NC-MRA

and CE-

MRA, although the image qual-ity

of NC-MRA is slightly lower with

signifcance

reached. Similarly, high

diagnostic accuracy was obtained using

the NC-MRA technique. An exmaple

case from [9] is shown in figure 4.

Pedal arteries present a few chal-lenges

to NC-MRA techniques, includ-ing

small caliber size, relatively slow

flow, and more tortuous anatomy.

FSD-based NC-MRA has recently been

successfully applied to diabetic

patients who have foot vascular com-plications

[10]. This work demon-strated

that the NC-MRA technique

can yield a significantly higher num-ber

of diagnostic arterial segments

4A 4B

CE-MRA (4A) and NC-MRA (4B) MIP images and X-ray angiography image (4C) of the right upper calf in a 65-year-old woman

with diabetes. NC-MRA clearly depicts luminal narrowing at the proximal anterior tibia artery (ATA) and peroneal artery consistent

with X-ray angiography (arrows). Also, NC-MRA clearly depicts collaterals (arrowheads) with less venous contamination compared

to CE-MRA in the location of a complete occlusion of proximal posterior tibia artery (PTA).

4

Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 5

Sequence diagrams and example images using the single-module FSD preparative scheme versus two-module FSD

preparative scheme. Notice that signal defects are observed at several arterial segments (arrows, generally located

at the 90° with respect to the vector sum of the readout and phase-encoding directions) on single module-based

NC-MRA, which are dramatically improved on two module-based NC-MRA.

3

ATA

PTA

PTA

ATA

ATA

4C

PTA

3C 3D

90°x 180°y 90°-x

RF

GRO

S

90°x 180°y 90°-x

GPE

S

12 ms 12 ms

3B

m1,PE

m1,RO m1,PE

Technology MR Angiography](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-3-2048.jpg)

![5A 5B

DA

Right Right

6A 6B

6

A 33-year-old female with SLE for 13 years

and hand symptoms for 10 years. FSD

demonstrates excellent visualization of

the palmar vessels and excellent to good

visualization of the digital vessels. There

is mild venous contamination which does

not affect the diagnostic quality of the

images. TWIST images have good separation

of arterial and venous phases but relatively

poor opacification of digital vessels.

CE-MRA has very good resolution but

significant venous contamination limiting

visualization of digital vessels.

6C

MR Angiography Technology

Contact

Debiao Li, Ph.D.

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

116 N. Robertson Blvd,

Suite 800

Los Angeles, CA 90048

USA

Phone: +1 310-423-7743

debiao.li@cshs.org

References

1 Thomsen HS. Nephrogenic systemic

fibrosis: A serious late adverse reaction

to gadodiamide. Eur Radiol 2006;

16:2619-21.

2 Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, et al.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected

causative role of gadodiamide used for

contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance

imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol

2006;17:2359-62.

3 Miyazaki M, Lee VS. Nonenhanced MR

angiography. Radiology 2008; 248:20-43.

4 Miyazaki M, Sugiura S, Tateishi F, et al.

Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography

using 3D ECG-synchronized half-Fourier

fast spin echo. J Magn Reson Imaging

2000;12:776-83.

5 Edelman RR, Sheehan JJ, Dunkle E, et al

Quiescent-interval single-shot

unenhanced magnetic resonance angiog-raphy

of peripheral vascular disease:

Technical considerations and clinical feasi-bility

.Magn Reson Med 2010; 63:951-8.

6 Koktzoglou I, Edelman RR. Ghost Magnetic

Resonance Angiography. Magnetic

Resonance in Medicine, 2009,

61:1515–1519.

7 Fan Z, Sheehan J, Bi X, et al. 3D

noncontrast

MR angiography of the distal

lower extremities using flow-sensitive

dephasing (FSD)-prepared balanced SSFP.

Magn Reson Med 2009; 62:1523-32.

8 Lim RP, Fan Z, Chatterji M, et al.

Comparison of nonenhanced MR angio-graphic

subtraction techniques for infra-genual

arteries at 1.5 T: A preliminary

study. Radiology 2013; 267:293-304.

9 Zhang N, Fan Z, Feng F, et al. Clinical

evaluation of peripheral non-contrast

enhanced MR angiography (NCE-MRA)

using steady-state free precession (SSFP)

and flow sensitive dephasing (FSD) in

diabetes. In Proceedings of the 20th

Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Melbourne,

Victoria, Australia, 2012; p. 730.

10 Fan Z, Liu X, Zhang N, et al. Non-contrast

enhanced MR angiography (NCE-MRA)

of the foot using flow sensitive

dephasing (FSD) prepared steady-state

free precession (SSFP) in patients with

diabetes. In Proceedings of the 21st

Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Salt Lake City,

Utah, USA, 2013; p.5799.

11 Sheehan JJ, Fan Z, Davarpanah AH, et al.

Nonenhanced MR angiography of the

hand with flow-sensitive dephasing-prepared

balanced SSFP sequence: initial

experience with systemic sclerosis.

Radiology 2011; 259:248-56.

12 Saouaf R, Fan Z, Ishimori ML, et al.

Comparison of noncontrast FSD MRA to

time resolved (TWIST) and high

resolution contrast enhanced MRA of the

hands in patients with systemic lupus

erythematosus (SLE) and clinical vascu-lopathy.

In Proceedings of the 21st

Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Salt Lake City,

Utah, USA, 2013; p.3963.

13 Wedeen VJ, Meuli RA, Edelman RR, et al.

Projective imaging of pulsatile flow with

magnetic resonance. Science 1985;

230:946 –948.

14 Meuli RA, Wedeen VJ, Geller SC, et al.

MR gated subtraction angiography:

evaluation of lower extremities. Radiology

1986; 159:411– 418.

15 Becker ED, Farrar TC. Driven equilibrium

Fourier transform spectroscopy. A new

method for nuclear magnetic resonance

signal enhancement. J Am Chem Soc

1969; 91:7784-7785.

16 Haacke EM, Brown RW, Thompson MR,

Venkatesan R. Magnetic resonance

imaging physical principles and sequence

design. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1999,

pp. 673.

17 Fan Z, Zhou X, Bi X, et al. Determination

of the optimal first-order gradient moment

for flow-sensitive dephasing magneti-zation-

prepared 3D noncontrast MR

angiography. Magn Reson Med 2011;

65:964-72.

18 Sirol M, Itskovich VV, Mani V, et al.

Lipid-

rich atherosclerotic plaques

detected by gadofluorine-enhanced

in vivo magnetic resonance imaging.

Circulation

2004; 109:2890-2896.

19 Koktzoglou I, Li D. Diffusion-prepared

segmented steady-state free precession:

Application to 3D black-blood cardiovas-cular

magnetic resonance of the thoracic

aorta and carotid artery walls. J

Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2007; 9:33-42.

20 Wang J, Yarnykh VL, Hatsukami T, et al.

Improved suppression of plaque-mimicking

artifacts in black-blood carotid

atherosclerosis imaging using a multislice

motion-sensitized driven-equilibrium

(MSDE) turbo spin-echo (TSE) sequence.

Magn Reson Med 2007; 58:973-981.

21 Fan Z, Hodnett P, Davarpanah A, et al.

Noncontrast magnetic resonance angiog-raphy

of the hand: Improved arterial

conspicuity by multidirectional flow-sensitive

dephasing (FSD) magnetization

preparation in 3D balanced steady-state

free precession imaging. Investigative

Radiology 2011; 46:515-523.

22 Connell DA, Koulouris G, Thorn DA,

Potter HG. Contrast-enhanced MR

angiography of the hand. Radiographics

2002; 22:583-599.

compared to CE-MRA (93% vs. 65%).

The average image quality score of

NC-

MRA is also significantly higher.

An example case from [10] is shown

in figure 5.

Additionally, FSD-based NC-MRA has

also found a unique application in

patients with autoimmune disorders

characterized by vasculopathies in the

hands. Lesions are primarily involved

in proper digital arteries, and the

diagnostic performance of CE-MRA

can be compromised in imaging this

station whereby small vessel caliber

and short arteriovenous transit times

present competing demands of high

spatial resolution and short imaging

time [22]. The pilot study of Reynaud

phenomenon by Sheehan et al. [11]

showed that FSD-based NC-MRA yield

a lower degree of stenosis as com-pared

with both high-resolution static

CE-MRA and time-resolved CE-MRA,

suggesting that “FSD findings may be

more accurate determinants of vessel

diameter”. When utilizing the multi-directional

FSD scheme, our recent

investigation of systemic lupus ery-thematosus

disease demonstrated

that FSD-based NC-MRA is superior

to CE-MRA in visualizing arterial seg-ments

in all hand vascular regions,

and particularly the 3rd terminal digi-tal

arteries are much better depicted

[12]. A clincal case from this work is

shown in figure 6.

Conclusion

FSD-based balanced SSFP is a promis-ing

NC-MRA approach to the diagno-sis

of peripheral arterial disease in

various vascular regions. This method

eliminates the intravenous injection

of contrast medium and prevents

adverse contrast reaction and compli-cations

while reducing the medicla

expense. Most importantly, the use

of this approach in clinical practice will

greatly benefit patients with impaired

kidney function. Preliminary patient

studies have demonstrated very prom-ising

clinical value. However, this

technique still awaits clinical valida-tions

with large-size patient popula-tion

to establish itself as a routine non-contrast

MRA diagnostic tool.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the col-leagues

from Siemens Healthcare,

especially Renate Jerecic, Sven

Zuehlsdorff,

and Gehard Laub.

CE-MRA (5A) and NC-MRA (5B) MIP images of bilateral feet in a 64-year-old female with diabetes. Compared to CE-MRA images,

NC-MRA shows excellent delineation of foot arteries without venous contamination. ATA = anterior tibia artery,

PTA = posterior tibia artery, DA = dorsal pedal artery, LPA = lateral plantar artery, MPA = medial plantar artery, Arch = pedal arch

5

PTA

LPA

LPA LPA LPA

DA

PTA

MPA

Arch

Arch

FSD-MRA TWIST

CE-MRA

26.1s

Technology MR Angiography

6 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US. Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-4-2048.jpg)

![Technology MR Angiography MR Angiography Technology

Non-Contrast-Enhanced ECG-Gated Quiescent

Interval Single Shot MR Angiography of the

Lower Extremities at 3 Tesla: a Case Report

superficial femoral artery (SFA), with

evidence of isolated collaterals and

only low poststenotic flow in the

popliteal artery. The iliac vessels could

not be fully evaluated due to overly-ing

intestinal gas. Based on the clini-cal

symptoms and the Doppler ultra-sound

findings, digital subtraction

angiography (DSA) was indicated.

Furthermore, a QISS MRA at 3T was

performed as part of a prospective

study prior to the DSA procedure.

Methods

QISS MRA is a 2D ECG-gated single-shot

balanced steady-state free-precession

(bSSFP) acquisition. The

sequence uses initial saturation pulses

which suppress both background

tissue

and venous blood flowing into

the imaging slice. This preparatory

phase is followed by the ‘quiescent

interval’ (QI), during which unsatu-rated

spins are carried into the imag-ing

slice by arterial blood. Subsequent

imaging is performed in diastole with

a 2D bSSFP sequence. For the QISS

MRA, the patient was positioned supine

in a 3T MR system (MAGNETOM Skyra,

Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Ger-many),

with his heels at the scanner-side

table end. The ECG signal for

triggering the image acquisition was

derived from the ECG system inte-

Gesine Knobloch1; Peter Schmitt2; Alexander Huppertz3; Moritz Wagner1

1 Department of Radiology, Charité Campus Mitte, Berlin, Germany

2 Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector, Imaging & Therapy Division, Erlangen, Germany

3 Imaging Science Institute Charité - Siemens, Berlin, Germany

Background

Non-contrast-enhanced magnetic

resonance

angiography (non-CE-MRA)

sequences have become of increasing

interest. Non-CE-MRA is a promising

alternative to contrast-enhanced MRA

or computed tomography angiogra-phy

(CTA), in particular for patients

with renal insufficiency. Recent

decades have seen the development

of various techniques for non-CE-MRA

sequences such as time-of-flight MRA

[1-4] and ECG-gated 3D partial-Fourier

fast spin echo techniques [5-10]. In

2010, Edelman et al. introduced Qui-escent

Interval Single Shot (QISS)

MRA as a new non-contrast-enhanced

technique for imaging the peripheral

arterial vascular system [11]. This case

report describes the use of QISS MRA

at 3 Tesla (T) for the preinterventional

imaging for a patient with peripheral

artery occlusive disease (PAOD).

Case description

A 66-year-old patient with peripheral

artery occlusive disease (PAOD), type

2 diabetes mellitus, nicotine abuse

(40 pack years) and arterial hyperten-sion

presented due to increasing inter-mittent

claudication and pain in the

left leg, originating from the calf. Due

to moderate symptoms in the past,

the patient had previously received

conventional treatment consisting of

vasoactive infusion therapy and

walking

exercises. Treadmill testing

revealed a reduction in the pain-free

walking distance from previously

385 m to now 165 m and deteriora-tion

of the left ankle-brachial index

from previously 0.6 to 0.3. Doppler

ultrasound findings were suggestive

of a short occlusion of the left middle

1 MIP of the QISS MRA.

1

30° rotated MIP of the QISS MRA

with high-grade stenosis at the

origin of the left SFA and occlusion

in the left middle SFA.

2A

grated in the MR scanner. For signal

readout, a combination of two

18-channel body coils for abdomen

and pelvis, the 36-channel peripheral

angio coil, and the 32-element spine

coil was used.

The other image parameters were as

follows: 400 x 260 mm² field-of-view

(FOV); measured voxel size, 1.0 × 1.0

× 3.0 mm³; reconstructed voxel size,

0.5 × 0.5 × 3.0 mm³; repetition time

(TR), 4.1 ms; echo time (TE), 1.74 ms;

flip angle per slab of 50°–120°,

depending on specific absorption rate

(SAR) limitations; parallel acquisition

(GRAPPA) with an acceleration factor

of 2 with a patient’s heart rate of

76-80 beats per minute (bpm); partial

Fourier in the phase-encoding direc-tion,

5/8. To span the entire arterial

system from the pelvis, over the legs,

to the feet, eight groups of 70 slices

were acquired with 3 mm slice thick-ness

and 0.6 mm overlap. Each slice

group covered 16.86 cm.

2B MPR shows the stenosis at the

MIP shows the occlusion in the

left middle SFA.

origin of the left proximal SFA.

2C

2A 2B

Result 3

Evaluation of the QISS MRA revealed

diffuse arteriosclerotic irregularities

in the wall of the abdominal aorta

and all peripheral arteries (Fig. 1).

Confirming the Doppler ultrasound

findings, an occlusion of 3 cm in

length of the left middle SFA was

detected (Fig. 2A, 2B). The mean

intensity projection (MIP) of the QISS

showed numerous collaterals via the

profunda femoris artery (PFA) and

side branches of the left SFA (Fig. 1).

Furthermore, there was bilateral

occlusion of the posterior tibial artery

(PTA, Fig. 1) as well as a high-grade

stenosis at the origin of the left SFA

(left femoral bifurcation, Fig. 2A, 2C),

which was missed in the Doppler

ultrasound.

Correlating well with the QISS MRA

findings, the diagnostic DSA per-formed

thereafter showed the diffuse

changes of the vessel wall with the

high-grade stenosis at the origin

of the left SFA, the collateralized

short occlusion of the left SFA, and

the bilateral occlusion of the posterior

tibial artery (Fig. 3, 4). Following

3 Stenosis at origin of left SFA.

2C

8 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US. Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-5-2048.jpg)

![Technology MR Angiography MR Angiography Technology

Contact

Moritz Wagner, M.D.

Department of Radiology

Charité, Campus Mitte

Charitéplatz 1

10115 Berlin

Germany

moritz.wagner@charite.de

References

1 Collins R, Burch J, Cranny G, et al. Duplex

ultrasonography, magnetic resonance

angiography, and computed tomography

angiography for diagnosis and assessment

of symptomatic, lower limb peripheral

arterial disease: systematic review. BMJ

(Clinical research ed). 2007;334:1257.

doi:10.1136/bmj.39217.473275.55.

2 Kaufman JA, McCarter D, Geller SC, et al.

Two-dimensional time-of-flight MR

angiography of the lower extremities:

artifacts and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

1998;171:129-35.

3 McCauley TR, Monib A, Dickey KW, et al.

Peripheral vascular occlusive disease:

accuracy and reliability of time-of-flight

MR angiography. Radiology.

1994;192:351-7.

4 Owen RS, Carpenter JP, Baum RA, et al.

Magnetic resonance imaging of angio-graphically

occult runoff vessels in

peripheral arterial occlusive disease.

N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1577-81.

5 Gutzeit A, Sutter R, Froehlich JM, et al.

ECG-triggered non-contrast-enhanced

MR angiography (TRANCE) versus digital

subtraction angiography (DSA) in patients

with peripheral arterial occlusive disease

of the lower extremities. Eur Radiol.

2011;21:1979-87. doi:10.1007/

s00330-011-2132-4.

6 Miyazaki M, Sugiura S, Tateishi F, et al.

Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography

using 3D ECG-synchronized half-Fourier

fast spin echo. J Magn Reson Imaging.

2000;12:776-83. doi:10.1002/1522-

2586(200011)12:5<776::AID-JMRI17>3.0.

CO;2-X [pii].

7 Miyazaki M, Takai H, Sugiura S, et al.

Peripheral MR angiography: separation

of arteries from veins with flow-spoiled

gradient pulses in electrocardiography-triggered

three-dimensional half-Fourier

fast spin-echo imaging. Radiology.

2003;227:890-6. doi:10.1148/

radiol.2273020227, 2273020227 [pii].

8 Haneder S, Attenberger U, Riffel P, et al.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)

of the calf station at 3.0 T: intraindividual

comparison of non-enhanced ECG-gated

flow-dependent MRA, continuous table

movement MRA and time-resolved MRA.

Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1452-61.

doi:10.1007/s00330-011-2063-0.

9 Lim RP, Hecht EM, Xu J, et al. 3D nongado-linium-

enhanced ECG-gated MRA of the

distal lower extremities: Preliminary

clinical experience. Journal of Magnetic

Resonance Imaging. 2008;28:181-9.

doi:10.1002/jmri.21416.

10 Mohrs O, Petersen S, Heidt M, et al. High-resolution

3D non-contrast-enhanced,

ECG-gated, multi-step MR angiography of

the lower extremities: Comparison with

contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Eur

Radiol. 2011;21:434-42. doi:10.1007/

s00330-010-1932-2.

11 Edelman RR, Sheehan JJ, Dunkle E, et al.

Quiescent-interval single-shot unenhanced

magnetic resonance angiography of

peripheral vascular disease: Technical

considerations and clinical feasibility.

4 Recanalization of the left SFA occlusion.

interdisciplinary discussion

of the

case, a two-stage treatment strategy

for the left leg was adopted. In the

first step, the stenosis of the left fem-oral

bifurcation was surgically cor-rected

by means of thromboendarter-ectomy

(TEA) and application of a

patch graft. Then another catheter

angiography was carried out and the

SFA occlusion was successfully recan-alized

and stented (Fig. 4). Shortly

thereafter, the patient was discharged

home with significantly improved

symptoms.

Discussion

QISS MRA was successfully used in

the diagnosis of a patient with PAOD.

Compared to the Doppler ultrasound

exam, QISS MRA provided additional

information on the extent and local-ization

of significant stenoses regard-less

of the examiner, allowing early

treatment decisions and planning.

In a previous study at 1.5T, the

diagnostic accuracy of QISS MRA was

evaluated

in 53 patients with sus-pected

or known PAOD [12]. QISS MRA

showed high sensitivity (89.7% and

87.0%, two readers) and specificity

(96.5% and 94.6%, two readers)

using CE-MRA as reference standard.

In a sub-group of 15 patients (279

segments), conventional DSA was

performed during a therapeutic inter-ventional

procedure or when MRA

revealed pathologic conditions that

warranted further investigation. In

these vessel segments, QISS MRA had

high sensitivity (91.0%, mean values)

and specificity (96.6 %, mean values)

using conventional DSA as reference

standard. The high sensitivity and

specificity of QISS MRA at 1.5T has

been confirmed in two other studies,

which also included patients with

PAOD and mainly used CE-MRA as

reference standard [13, 14]. Nowa-days,

3T MR scanners are increasingly

being used in clinical practice. A

recent volunteer study indicated that

QISS MRA benefits from higher field

strengths [15]. However, clinical

studies of QISS MRA at 3T have not

yet been published. One advantage of

QISS MRA over other MRA techniques

4A 4B

4C 4D

is that it is easy to use and does not

require preplanning of slice blocks or

calibration of sequence parameters

according to arterial flow patterns. In

our experience so far, QISS MRA takes

only slightly longer considering the

preparation time for planning scans

and testbolus of a conventional con-trast-

enhanced MRA. A limitation in

the present QISS examination was the

suboptimal suppression of the venous

signal. However, this had no substan-tial

impact on the assessment of the

peripheral arteries.

In summary, QISS MRA is an easy-to-use,

robust technique for unenhanced

imaging of the peripheral arteries.

QISS MRA could be a future alternative

to CE-MRA for preoperative diagnosis

and treatment planning for patients

with PAOD.

Magnetic resonance in medicine :

official journal of the Society of Magnetic

Resonance in Medicine / Society of

Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;

63:951-8. doi:10.1002/mrm.22287.

12 Hodnett PA, Koktzoglou I, Davarpanah AH,

et al. Evaluation of peripheral arterial

disease with nonenhanced quiescent-interval

single-shot MR angiography.

Radiology. 2011;260:282-93.

doi:10.1148/radiol.11101336.

13 Hodnett PA, Ward EV, Davarpanah AH,

et al. Peripheral arterial disease in

a symptomatic diabetic population:

prospective comparison of rapid

unenhanced MR angiography (MRA) with

contrast-enhanced MRA. AJR American

journal of roentgenology. 2011;197:

1466-73. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.6091.

14 Klasen J, Blondin D, Schmitt P, et al.

Nonenhanced ECG-gated quiescent-interval

single-shot MRA (QISS MRA)) of

the lower extremities: comparison with

contrast-enhanced MRA. Clinical radiology.

2012;67:441-6. doi:10.1016/j.

crad.2011.10.014.

15 Glielmi C, Carr M, Bi X, et al. High Acceler-ation

Quiescent-Interval Single Shot

Magnetic Resonance Angiography at 1.5

and 3T. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med.

2012;20:3876.

10 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US. Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-6-2048.jpg)

![Technology MR Angiography

Respiratory Self-Navigation for Free Breathing

Whole-Heart Coronary MR Imaging with

High Isotropic Spatial Resolution in Patients

Davide Piccini1, 3; Jürg Schwitter, M.D.2; Pierre Monney, M.D.2; Tobias Rutz, M.D.2; Gabriella Vincenti, M.D.2;

Christophe Sierro, M.D.2; Matthias Stuber, Ph.D.3

1 Advanced Clinical Imaging Technology, Siemens Healthcare IM BM PI, Lausanne, Switzerland

2 Division of Cardiology and Cardiac MR Center (CRMC), University Hospital of Lausanne (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland

3 Department of Radiology, University Hospital (CHUV) and University of Lausanne (UNIL) / Center for Biomedical Imaging (CIBM),

Lausanne, Switzerland

a - Navigator Gating

b - Self-Navigation

Illustration of a typical whole-heart navigator-gated acquisition sequence (1A) in

comparison to respiratory self-navigation (1B). In the gated setup, the additional

acquisition of a pencil beam navigator (in red) is needed to decide whether to reject and

re-acquire data segments acquired outside a specific respiratory phase. Conversely,

self-

navigation assesses motion directly in the readouts acquired for cardiac imaging and

allows for inline respiratory motion correction of all acquired data. While in (1A) the

final scan efficiency is generally low, uncertain and highly dependent on the respiratory

pattern of the examined subject, 100% scan efficiency and a priori knowledge of the

total scan time become possible with self-navigation. In particular, the technique applied

in the WIP makes use of a 1D readout constantly oriented along the head-foot direction

to track the position of the blood pool at each acquired heartbeat (as displayed in the

bottom-right corner).

1

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading

cause of death in industrialized

nations. In the US, 50% of these

deaths can be attributed to coronary

heart disease [1]. The gold standard

for the assessment of luminal coro-nary

artery disease remains X-ray

coronary angiography, an invasive

procedure that involves the insertion

of a catheter, injection of an iodin-ated

contrast agent and imaging

using X-ray fluoroscopy. For many

years, coronary MR angiography

(MRA) has been a potentially very

appealing alternative to routine inva-sive

procedures such as X-ray angio-graphy

or also, more recently, coro-nary

computed tomography (CT). MR

is non-invasive, safe, easily repeat-able,

and avoids exposure to ionizing

radiation for both patients and medi-cal

professionals [2]. Considering

that up to 40% of patients who

undergo the invasive gold standard

test X-ray angiography are found to

have no significant coronary artery

disease [3], a non-invasive test that

reliably rules out significant luminal

coronary artery disease would have

a great impact on patient manage-ment.

Furthermore, the integration

of a coronary acquisition protocol

into a routine clinical examination

that includes tissue characterization,

morphology characterization and the

measurement of function would sig-nificantly

enhance MR as the most

comprehensive imaging tool in con-temporary

cardiology.

As MR acquisitions are relatively slow

and high resolution is needed to

Example of the measurement planning. The cubic field-of-view must simply be centered in the blood pool of the left ventricle,

while the saturation slab needs to be placed over the chest wall. The self-navigated whole-heart sequence requires a minimal

amount of user interaction during scan planning. Fold-over is not a concern, as the 3D radial trajectory includes oversampling in

every spatial direction and no navigator placement is needed. Once the scan is started, the self-navigated motion detection can

be assessed directly in real time with the inline monitor display (bottom-right corner).

2

2

image the small dimensions of the

coronary

arteries, the scan is usually

segmented over several consecutive

heartbeats. ECG triggering is applied

to target the acquisition on the cardiac

phase with minimal myocardial motion

(usually mid-diastole or end-systole).

To account for the respiratory motion,

a pencil-beam navigator [4], most

commonly placed on the dome of the

right hemidiaphragm, provides a real-time

feedback on the respiratory posi-tion

along the major direction of dis-placement,

i.e. the superior-inferior (SI)

direction. A so-called gating (or accep-tance)

window is defined at end-expi-ration

to enforce the spatial consistency

of the dataset, such that only the seg-ments

acquired within such a window

are used for the reconstruction of the

final image. All other segments are

discarded and re-acquired later during

the scan. Prospective motion compen-sation,

known also as tracking [4, 5],

can additionally be performed on the

accepted segments by means of a fixed

correlation factor with the diaphrag-matic

displacement [6]. An example of

such navigator-gated acquisition is

depicted in Figure 1A.

Although major strides in respiratory

motion suppression have led to highly

promising results even in a multicenter

setting [7], a number of issues still

hinder a more widespread use and

acceptance of this technique. Firstly,

respiratory gating if associated with

irregular breathing patterns (which

often occur in coronary artery dis-ease

patients), can lead to low scan

efficiency, highly unpredictable scan-ning

times or even complete failure

of data acquisition. This makes coro-nary

MRA unattractive for integration

into a routine clinical

exam with time

and workflow constraints. Secondly,

the experience, confidence and

expertise of the operator with the

planning of the coronary measure-ment

is essential for a good out-come,

as a suboptimal placement of

the navigator can lead to even more

extended examination times or even

to the failure of the scan. Therefore,

the most promising results to date

have been obtained in academic cen-ters

with significant experience, but

even here the technique still suffers

from a limited ease-of-use and opera-tor

dependency. To remove those

constraints, respiratory self-naviga-tion

for coronary MRA has been intro-duced

in 2005 [8] and has been sig-nificantly

refined since [9, 10]. The

idea behind this technique is that

motion detection is performed using

the image data themselves, while

navigator placement can be avoided,

thus leading to a much reduced

operator

dependency. Motion correc-tion

is no longer based on a relation-ship

between diaphragm position

and heart position (which can vary

throughout the scan), but on the

heart position itself. Furthermore,

since the technique operates without

a gating window

and all data seg-ments

are accepted and corrected for

respiratory motion, scanning time

is highly predictable and no longer

dependent on the respiratory pat-tern.

This leads to a substantially

improved workflow. Finally, and since

3D radial acquisition is used, isotro-pic

spatial resolution is obtained and

fold-over is always avoided, which

further maximizes the ease-of-use.

Especially thanks to the true isotropic

resolution a detailed retrospective

interrogation of the sometimes com-plex

anatomy is enabled, which

removes the burden of a meticulous

scan plane planning during MR data

acquisition. This has shown to be

most valuable in cases with congeni-tal

heart disease. While to date only

1D motion correction has been

implemented as part of this highly

promising technique, the opportuni-ties

for multi-dimensional and non-linear

correction and reconstruction

schemes are vast and remain to be

explored, but will undoubtedly lead

to a quantum leap in image quality,

detail visibility, and ultimately more

widespread acceptance of the method.

1A

1B

12 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US. Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-7-2048.jpg)

![Example of self-navigated whole-heart coronary acquisition on a healthy volunteer without the use of contrast agent.

The sagittal (3A), coronal (3B), and axial (3C) views demonstrate the true 3D high isotropic spatial resolution of the datasets.

After the acquisition is completed, offline multiplanar reformatting can be used to visualize the coronary arteries (3D).

3

Patient studies

As the total acquisition time is known

a priori and only depends on the heart

rate of the examined subject, it is now

possible to optionally integrate the

free breathing self-navigated whole-heart

coronary acquisition into a com-plete

clinical cardiac MR examination

with minimal or no impact on the total

examination time. Given that the per-formance

of self-navigation in part

depends on myocardium-blood con-trast,

and provided that there is often

a time gap between perfusion imaging

and late gadolinium enhancement

(LGE) imaging in routine clinical proto-cols,

high-resolution self-navigated

3D whole-heart imaging may easily be

performed to obtain information on

both the general cardiac anatomy and

the coronary tree. A first patient study

using this WIP sequence was conducted

at the university hospital of Lausanne

(CHUV), in Switzerland in collaboration

Whole-heart coronary MRI

with respiratory

self-navigation WIP

The self-navigated whole-heart coro-nary

MRI sequence1 consists of a

segmented

radial 3D acquisition

incorporating a spiral phyllotaxis pat-tern,

as described in [9]. Such 3D

radial trajectory is intrinsically robust

against motion, spatial undersam-pling,

and foldover artifacts. More-over,

it achieves reduced eddy currents

effects, while ensuring a uniform

coverage of k-space. At the start of

each data segment, a readout is

acquired with a consistent orienta-tion

along the SI direction. The algo-rithm

for automatic detection and

segmentation of the blood pool

described in [10] is then applied to

the 1D Fourier transform of these SI

readouts. After segmentation, the

SI displacement of the heart due to

respiratory motion is tracked in real

time during the acquisition using a

modified cross-correlation algorithm.

The whole acquisition set-up is highly

simplified and, once the scan is

started, a feedback from the motion

detection algorithm can be visualized

in real time with the inline monitor

display (Fig. 2). Motion compensation

is automatically performed before

image reconstruction at the scanner.

An example dataset acquired without

contrast agent in a healthy adult vol-unteer

is displayed in figure 3. The

described self-navigated technique

was previously compared to the stan-dard

navigator-gated acquisition in

a number of volunteers in [10] and

some of the results are reported in

figure 4.

1 Work in progress: The product is still under

development and not commercially available

yet. Its future availability cannot be ensured.

14 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US.

with the CVMR team of Prof. Matthias

Stuber and the Cardiac MR Center

(CRMC) of Prof. Jürg Schwitter.

More than 250 patient datasets were

acquired in a period of about 8 months.

The choice of acquiring the self-navi-gated

coronary sequence was taken by

the responsible clinician and technolo-gist

on a case-by-case basis. All exami-nations

were performed on a 1.5T

MAGNETOM Aera (Siemens Healthcare,

Erlangen, Germany) during the wait

time between perfusion imaging and

2D LGE. A total of 30 elements of the

anterior and posterior phased-array

coils were activated for signal reception.

All measurements were performed

using k-space segmentation and ECG-triggering.

For the acquisition of each

k-space segment, both T2-preparation

(TE 40 ms) and fat saturation were

added prior to balanced steady-state

free precession (bSSFP) image data

acquisition. The 3D self-navigated

acquisition started approx.

4 min after injection of a bolus of

0.2 mmol/kg of Gadobutrol (Gadovist,

Bayer Schering Pharma, Zurich, Swit-zerland).

Imaging was performed with

the following parameters: TR 3.1 ms,

TE 1.56 ms, FOV (220 mm)3, matrix

1923, acquired true isotropic voxel

size (1.15 mm)3, RF excitation angle

115°, and receiver bandwidth

900 Hz/Px. A total of about 12,000

radial readouts were acquired during

377 to 610 consecutive heartbeats

with different acquisition windows,

depending on the individual heart

rate of each patient. The trigger delay

was set using visual inspection of the

most quiescent mid-diastolic or end-systolic

period on a mid-ventricular

short axis cine image series acquired

prior to the injection of contrast agent.

Results and discussion

The acquisition time of the 3D whole-heart

dataset always fitted in the

wait time after perfusion imaging and

before 2D LGE. Some example refor-mats

of the coronary arteries are

displayed

in figure 5. The normal

or anomalous origin and proximal

course of the coronary arteries, with

respect to the anatomy of the heart

and the great vessels, could be

assessed in all cases. An example of

anomalous coronary artery, acquired

in collaboration with Dr. Pierre

MR Angiography Technology

Monney,

is reported in figure 5D.

Although further advances are

needed for improved diagnostic per-formance

for the detection of

significant

coronary artery disease,

anomalous coronary arteries can

reliably

and routinely be already

assessed. Complex anatomy in con-genital

patients can retrospectively

be studied with a high and isotropic

spatial resolution and some of the

datasets (Fig. 6) have already showed

great promise for the identification

of significant proximal coronary

artery disease with X-ray coronary

angiography as the gold standard.

The proposed technique removes

several of the roadblocks to success-ful

high resolution whole-heart

cardiac

imaging. Firstly, the scan

duration is well-defined and no lon-ger

respiration dependent. This makes

the protocol a reliable module that

can easily be integrated into a com-prehensive

clinical cardiac protocol.

Secondly, navigator scout scanning

and volume targeting can be avoided

while fold-over no longer occurs due

to oversampling in all spatial direc-tions.

This makes the technique less

3A 3B

3C 3D

4A 4B 4C

4A 4B 4C

Localizers 2

Scan time ~15 min

Resp. efficiency < 50 %

Navigator gating

Localizers 1

Scan time 377 hb

Resp. efficiency 100 %

Self-navigation

The whole-heart coronary sequence with respiratory self-navigation was compared with the state of the art navigator gated

technique in 10 healthy volunteers [10]. Example reformats of two right coronary arteries (RCA) and one left anterior descending

artery (LAD) are displayed, respectively, in (4A), (4B) and (4C). No significant difference could be measured in the vessel

sharpness of the coronary arteries. As depicted in these images, in cases of low acceptance rate of the navigated scan, a visual

improvement can be noticed in the self-navigated acquisitions (arrows).

4

Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 15

Technology MR Angiography](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-8-2048.jpg)

![How I Do It How I Do It

other methods of sedation

can be

utilized.

Coil selection

Selection of the coil that closely

matches the patient size and pre-dicted

imaging field-of-view is impor-tant

for maximizing MR signal. For

imaging the pediatric cardiovascular

system, we select from four available

coils. We have dedicated protocols for

each of these coils, with isotropic res-olution

optimized to the patient size.

Higher resolution protocols were also

built for coronary origin imaging

(Table 1).

Special purpose (4-channel array) coil

works best with neonates and infants

under 10 kg weight (Fig. 1A), and two

such coils may be applied in a clam-shell

configuration (Fig. 1B).

Small Flex (4-channel array) coil works

best for infants over 10 kg weight.

Large Flex (4-channel array) coils work

best for toddlers and small children,

and these may be combined with a

posterior spine array coil (Fig. 1D).

Another option for toddler size is to

use two special purpose coils, both

anterior in combination with the pos-terior

spine array coil (Fig. 1C).

Body Matrix (18-channel array) coils

work best for large children through

adult-sized patients and this may be

combined with a posterior spine array

coil (Fig. 1E).

Contrast administration

Using a power injector with right

antecubital 22 gauge or larger IV, we

administer a single dose of Ablavar

(0.03 mmol/kg or 0.12 ml/kg) at a rate

of 2.5–3.0 ml/s, followed by a sterile

saline flush of 1 ml/kg (up to max

10 ml). We perform TWIST dynamic

imaging during the contrast injection,

followed by the 3D Nav_IR_Flash

imaging within 15 minutes (up to an

hour) [1] for optimal vascular con-trast

enhancement.

Exam protocol

All imaging is performed on

a 1.5T MAGNETOM Aera scanner

(

Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen,

Germany).

Workflow for cardiovascular

MRA exam:

1. 3 plane TrueFISP breath-hold

localizers

2. Interactive real-time TrueFISP to

locate and save a clear 4-chamber

view

3. Single slice 4-chamber high tempo-ral

resolution cine TrueFISP imag-ing

for calculation of quiescent

time. It is acquired during free

breathing with 3–4 averages (60

true cardiac phases per heart beat).

Scroll through the cine images in

the viewer card to find the optimal

trigger time in the cardiac cycle

when the coronaries are most sta-tionary

(located in the atrioventric-ular

grooves). Often the quiescent

period is found in diastole for lower

heart rates (50–80 bpm) and sys-tole

for higher heart rates (80+

bpm). The trigger time (TT) of each

frame is located on the lower left

corner of the image text. Mark the

two specific TT’s at the start and

end times of the quiescent period

in the cardiac cycle. These two spe-cific

TT’s will be used to set up the

timing parameters

for the Nav_IR_

Flash. Figures 2A and 2B show one

example of setting up the quies-cent

time for Nav_IR_Flash.

4. Ablavar administration

5. Coronal dynamic TWIST imaging

(temporal resolution 2.5 s/frame)

6. 3D Nav_IR_Flash_TI_260_Coronal/

Axial Oblique. This sequence is

scanned after the single dose injec-tion

on TWIST sequence. Figure 2C

shows the optimal trigger parameter

adjustments to acquire data

during the quiescent period.

Imaging can be performed at 3T.

Alteration in the protocol for 3T imag-ing

includes changing the inversion-recovery

time (TI) to 350 ms and flip

angle to 15 degrees.

Setting up the Nav_IR_Flash

sequence:

A. Plan from all 3 plane breath-hold

localizers

B. The Nav_IR_Flash sequence can be

converted from the T2-prepared

TrueFISP sequence by following the

parameters in Table 1.

C. In the Physio tab begin with click-ing

on capture cycle, then adjust

the number of segments to reach

the desired data window duration

time, and then adjust the trigger

delay to reach the desired data

window start time. Hover over the

trigger delay with cursor to see the

changes in the tooltips popup. For

example, if the quiet period of the

cardiac cycle (from the high resolu-tion

free breathing 4-chamber cine

image) is from TT 626 to TT 759,

then the data window start time

should be set to 626 and the data

window duration should be set to

133 (Fig. 2C).

D. Place the intersection of the cross-pair

navigators in the middle of the

dome of the liver as viewed from

the axial localizer (Fig. 3A). Then

right-click, perpendicular from the

axial image to find the navigator

on the corresponding sagittal and

coronal planes to verify its optimal

location centered at the level of

the diaphragm (Figs. 3B, C). Work-ing

on the axial plane, one can

slightly rotate the oblique navigator

away from the heart if it crosses

anatomy; however must not rotate

the orthogonal navigator (aligned

in anterior-posterior direction).

‘Couple graphics’ should be ‘off’ for

the dual navigator set up.

E. Before starting the scan, first run

the sequence in scout mode, check

the ‘Scout mode’ box in Physio-

PACE card (Fig. 3G). Open the Inline

Display window during the scout

mode to get the position histo-gram,

‘mode number’ (Figs. 3D, E).

Next, apply the mode number into

the ‘search position (red)’ and

uncheck the scout mode to run the

full scan. When viewing the navi-gator

signal within the Inline Dis-play

window, the green bar (Accept

3A 3B 3C

3D 3E 3F

Cross-pair navigator positioning (3A–C). Navigator scout (3D) gives position histogram for ‘Mode number’ (3E) calculation,

to determine the ‘search postion (red)’ for optimal navigator waveform during Nav_IR_Flash acquistion (3F).

3

3G

20 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US. Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-11-2048.jpg)

![Technology MR Angiography MR Angiography Technology

Heart

Beat #

1

2

⋅

⋅

⋅

Outer Loop

(Slice-Enc.,kz)

Inner Loop

(Phase-Enc., ky)

Arterial window

Time

arterial

phase

venous

phase

Trigger

Delay

Inner Loop 1

Wait Time

Trigger

Delay

Inner Loop 2

Wait Time

Heart Beat #1 Heart Beat #2

• • •

The conventional approach to ECG-gated CE-MRA. In each heartbeat, all phase-encoding steps of a single slice-encoding line are

acquired. The TTC can be matched with the contrast timing since each triggered shot is acquired in linear order in slice direction.

2

ECG

2

of the acquisition. Furthermore, the

conventional gated CE-MRA technique

cannot reduce scan time by taking

advantage of parallel acquisition tech-nique

(iPAT) and partial Fourier in

phase encoding direction; if either of

these parameters is modified, the

total scan time remains the same since

conventional CE-MRA only a single

complete inner loop is played out per

heartbeat, regardless of its duration.

Moreover, the unpredictable nature

of the ECG-triggering adds some

uncertainty to the gated CE-MRA

method. While the sequence assumes

a steady R-R interval and uses a fixed

acquisition window, due to physiolog-ical

irregularities (the R-R interval can

vary during a breath-hold [5]) and

mechanical imperfections (ECG detec-tion

device can fail), trigger events

can be either detected too early or

too late to substantially increase the

scan time. The CE-MRA sequence has

a strict timing requirement with the

contrast arrival, and any deviation from

this may result in a contrast washout

with missed optimal timing.

This paper highlights recent advance-ments

in the ECG-gated CE-MRA

approach* that address these short-comings.

With these advancements,

high-resolution, full coverage ECG-gated

CE-MRA exams can be realized

within a single breath-hold.

* The sequence is currently under develop-ment

and is available as a work-in-progress

package (#691B for VB17A and #791 for

VD11D/13A); it is not for the sale in the US

and other countries. Its future availability

cannot be guaranteed.

Flexible trigger

segmentation

To improve the efficiency of the rigid

trigger segmentation in conventional

gated CE-MRA, we propose a flexible

approach (Fig. 3). Here, the inner

loop is not restricted to a single dimen-sion

in k-space. The points that are

sampled within the individual triggered

segments are determined with a fuzzy

pseudo-random algorithm. As a result,

the size and shape of the triggered

segments are no longer restricted.

In addition, the flexible triggered

segmentation can freely adjust the

acquisition order, both within and

in between triggered segments.

Not for distribution in the US. MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world 33

Advancements in the ECG-Gated

Contrast-Enhanced MR Angiography

Yutaka Natsuaki, Ph.D.1; Randall Kroeker, Ph.D.1; Gerhard Laub, Ph.D.1; Peter Schmitt2; J. Paul Finn, M.D.3

1 Siemens Healthcare, CA, USA

2 Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector, Imaging & Therapy Division, Erlangen, Germany

3 Diagnostic Cardiovascular Imaging, Department of Radiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, CA, USA

phase, where the cardiac motions

are most prominent. With proper

contrast

injection timing, the arterial

window can still be matched with the

center of the k-space in the outer

loop (i.e. slice encoding) direction.

With this scheme, the total scan time

corresponds to the average R-R inter-val

multiplied by the total number

of slice encoding steps.

Non-Gated

CE-MRA

Gated

CE-MRA

Time To Center (TTC)

Time To Center (TTC)

The major drawback of this conven-tional

acquisition inefficiency. A typical high-resolution

less than 200 phase encode steps in

ky direction. Hence, the data acquisi-tion

much shorter than the average R-R

interval, which reduces the efficiency

k=0

k=0

gated CE-MRA approach is its

non-gated CE-MRA proto-col

uses short TR times of 2.7 ms and

window during each heartbeat is

k

k

Non-gated CE-MRA vs. gated CE-MRA. Darker purple color bar represents the outer

k-space in both phase (ky) and slice (kz) encoding steps, and the lighter purple repre-sents

the inner k-space. The center of both phase and slice encoding steps (ky=0,

kz=0) is represented by k=0. Typically in CE-MRA, the contrast arrival timing is matched

with the center acquisition of the phase and slice encoding steps (i.e. considering

the time-to-center, TTC) for the optimal image contrast. For non-gated CE-MRA, the

data is acquired in a single continuous delayed centric trajectory, where phase and

slice encoding steps start from the outer k-space, then acquire inner k-space & k=0,

and finally the rest of the outerk-space to complete the scan. For the gated CE-MRA,

the acquisition is segmented (e.g. Fig. 2) and acquired in sync with the

ECG-triggering.

ECG

1

Introduction

For most of the current contrast-enhanced

MR angiography (CE-MRA)

examinations, the acquisition is

optimized

for the image contrast

enhancement by matching the con-trast

arrival timing with the acquisi-tion

of the central phase encoding

steps (i.e. time-to-center, TTC) [1].

The total scan time is kept short within

a breath-hold length (less than 25 s)

to suppress bulk breathing motion.

Typically, the CE-MRA data are acquired

without ECG-gating in a single

contin-uous

delayed centric trajectory (Fig. 1,

non-gated CE-MRA). While, for most

purposes, this approach is entirely

satisfactory, in CE-MRA of the thorax

the cardiac chambers and ventricular

outflow vessels can be delineated

with a certain degree of blurring with

non-gated acquisition. To address this

limitation, CE-MRA can be acquired

with ECG gating, whereby the seg-mented

data acquisition is synchro-nized

with the cardiac cycle [2, 3, 4]

(Fig. 1, gated CE-MRA).

The current product version of the

CE-

MRA sequence (fl3d_ce) supports

ECG gating with a rigid trigger seg-mentation

(Fig. 2, conventional gated

CE-MRA). For every trigger pulse, the

conventional gated CE-MRA acquires

all phase encoding steps for a single

value of the slice encoding gradient.

The acquisition is then repeated in

linear order for all slice encoding val-ues.

With a suitable trigger delay (TD),

the center of k-space in the inner loop

(i.e. phase-encoding) direction (ky = 0)

can be acquired outside of the sys-tolic

1

32 MAGNETOM Flash | 3/2013 | www.siemens.com/magnetom-world Not for distribution in the US.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetomflash53angiography-00934901-140821154918-phpapp02/75/MR-Angiography-Edition-Issue-53-17-2048.jpg)

![How I Do It How I Do It

Contrast-Enhanced MRA

in Practice: Tips and Caveats

Sarah N Khan, M.D.1; Yutaka Natsuaki, Ph.D.2; Wenchao Tao1, M.S.; Gerhard Laub, Ph.D.2; J. Paul Finn, M.D.1

1 Diagnostic Cardiovascular Imaging, Department of Radiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, CA, USA

2 Siemens Healthcare, CA, USA

Introduction

At UCLA, we perform contrast-enhanced

MR angiography (CE-MRA)

in adults and children* of all ages,

covering most vascular territories.

In this short article, we will consider

thoracic and abdominal applications,

although similar principles apply

also to carotid and extremity MRA.

In some patients, CE-MRA is performed

as a stand-alone procedure and in

other cases it is combined with cardiac

MRI, brain MRI or abdominal MRI.

In all cases, some common rules and

guidelines apply in the setup and

execution

of the studies.

Although several non-contrast MRA

techniques exist and continue to

undergo development, CE-MRA is

generally faster, less flow-dependent

and more reliable than its non-con-trast

enhanced counterparts.

First, it is important to realize that

CE-

MRA is a procedure, not just a

pulse sequence, and each step should

be planned. A high performance 3D

pulse sequence is a prerequisite, but

on its own it is insufficient. For first

pass imaging, accurate timing of the

contrast bolus is crucial and in all

cases it is essential to avoid patient

motion artifact [1-15]. If we mistime

the bolus or the patient moves during

the acquisition, the study will be

degraded or non-diagnostic, no matter

how good the contrast agent or sys-tem

hardware.

At the time of writing, the U.S.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

has approved the usage of two gado-linium

based contrast agents for

vascular

imaging applications with

MR. These are gadofosveset (‘Ablavar’,

Lantheus Medical) and Gd BOPTA

(‘Multihance’, Bracco Diagnostics)

frequently than the peripheral por-tion

and data from neighboring

peripheral k-space sets are shared.

A detailed consideration of TWIST

parameters is beyond the scope of

this work, but we will simply state

that in all of our CE-MRA studies, we

use TWIST with very low dose Gd as

a timing run for the high-resolution

CE-MRA acquisition and sometimes

we acquire an additional breath-held,

low dose TWIST between the timing

run and the main Gd injection for the

high resolution study.

Based on the TWIST timing run, we

can read off the time it takes for the

test bolus to reach an early peak in

the vessel of interest (e.g. aorta). We

will then use this time as the starting

time for the high-resolution acquisi-tion

with infusion of the main con-trast

bolus. As mentioned above, the

center of k-space within the high-res-olution

(20 second) acquisition can

be positioned freely by the user, using

the TTC parameter in the exam card.

Some principles guide our choice of

the TTC.

1. The contrast bolus must be in the

vessels of interest when we acquire

the center of k-space. If the center

of k-space is acquired before the

bolus arrives, we will fail to show

the major vessels and the study will

be non-diagnostic. This is a worst-case

scenario and is sometimes

referred to as ‘high pass filtering’

because the low spatial frequencies

are compromised and only the high

spatial frequencies are ‘passed

through’. Without low spatial fre-quency

information, the study is

useless.

2. The contrast bolus should persist

for long enough in the vessels of

interest to encompass not just the

center of k-space, but the periph-ery

also. If the bolus is too short

and covers only the center of

k-space, large vessels may appear

bright but the images will be

blurred and fine edge detail will

be compromised. This is sometimes

referred to as ‘low pass filtering’

because the high spatial frequencies

are compromised and only the

low spatial frequencies are ‘passed

through’.

Contrast agent ‘preparation’ –

we dilute! Why?

In 2007, the association between

nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF)

and gadolinium administration in

patients with renal failure was discov-ered

[18-21]. It became clear that the

high doses of Gd used routinely for

CE-MRA were particularly problem-atic,

and as a community we imple-mented

immediate and sometimes

draconian restrictions and dose reduc-tions

in the use of Gd. As a result,

NSF has virtually disappeared and no

new cases have been confirmed in

the past several years.

In the process of evaluating dose

reduction regimens for CE-MRA, we

were faced with some issues of imple-mentation.

The good news is that it

has proved feasible to reduce the dose

of Gd by a factor of 3-4 at 3T and of

2 at 1.5T, relative to what we used to

use in the past. So instead of using

double or triple dose (0.2–0.3 mmol/kg)

extracellular contrast agents, we can

still get very good results with single

dose or half-dose (0.05–0.1 mmol/kg)

[22]. The challenge is how to admin-ister

the lower dose while maintaining

the desired time course for the con-trast

bolus. So, for example, if we used

to use 30 ml of undiluted Gd over

15 seconds (injected at 2 ml/s) for

an average adult patient at 3T, we

might now want to use a quarter of

that dose (7.5 ml). If we inject at

2 ml/s, the entire amount is infused

in 3.5 seconds and we get a very

short peak. This will very likely result

in the ‘low pass filtering’ effect we

described above. If we extend the

infusion period to our 15 second target

by injecting at 0.5 ml/s, timing

may become unreliable for first pass

imaging because in some patients

the small volume of contrast may get

held up in the veins of the thoracic

inlet. An approach we have found

very reliable is to dilute the Gd back

up to the original volume (30 ml) and

inject the dilute solution at the origi-nal

rate (2 ml/s). The shape of the

contrast bolus will be exactly as it was

with the full strength Gd, but the

peak concentration will be propor-tionately

lower. Experience and theo-retical

considerations confirm that

the reduction in signal-to-noise ratio

3. We have found that a default

TTC of 6 seconds results in reliable

CE-MRA in most cases. Six seconds

is a typical value for contrast to

move from the arterial inflow to

the venous outflow of organs such

as brain, lungs and kidneys, so the

early peak of the arterial signal and

the center of k-space occur prior

to the venous peak. In children or in

cases where rapid venous enhance-ment

occurs on the timing run,