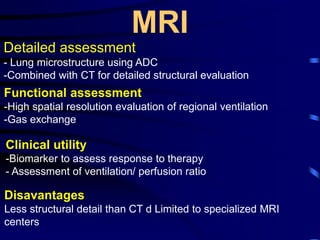

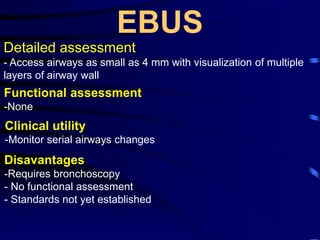

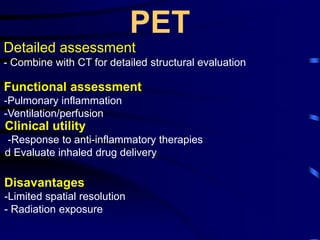

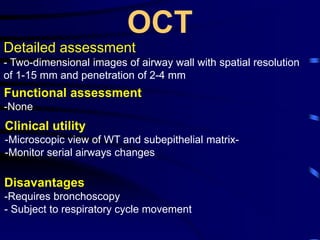

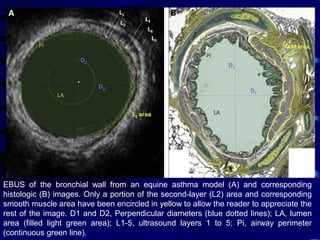

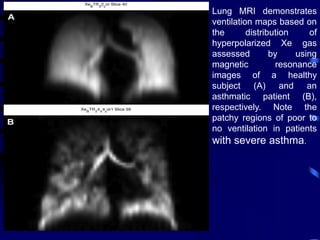

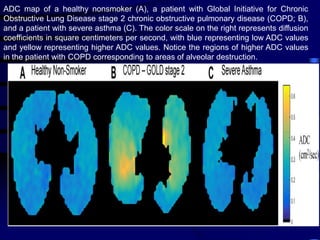

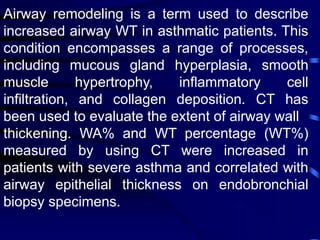

1. Several imaging modalities can provide detailed assessment of lung structure and function in asthmatic patients, including CT, MRI, PET, OCT, and EBUS.

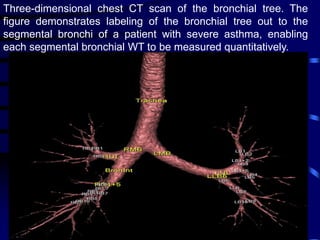

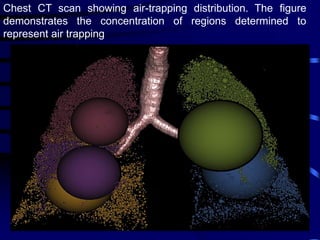

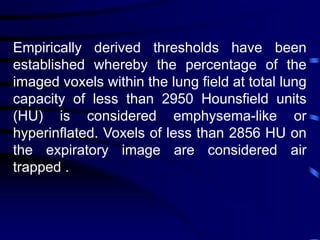

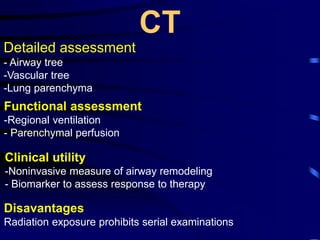

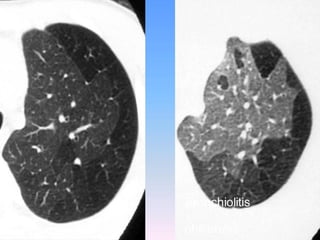

2. Measurements from CT such as airway wall thickness, air trapping, and ventilation defects have been shown to correlate with disease severity and control.

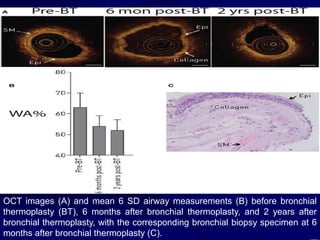

3. Imaging measurements can serve as biomarkers to evaluate responses to new therapies like inhaled corticosteroids and anti-IL5 monoclonal antibodies, and determine if treatments are modifying the disease course.

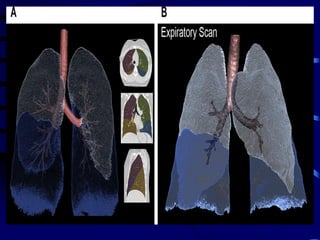

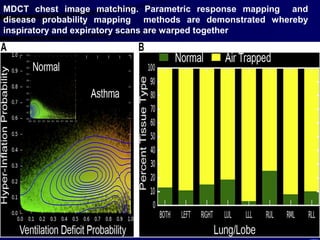

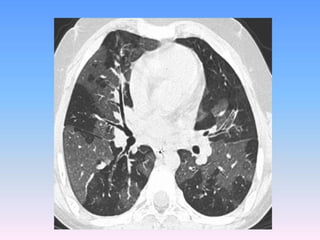

![The contributions of CT to an improved

understanding of the lungs has been recently

reviewed.Typically, imaging is performed at

full inspiration (total lung capacity [TLC]; and

end expiration, either at residual volume or

functional residual capacity .Protocols for

specific scanners and automated image

analysis software are used to identify the

lungs, lobes ,airway tree , and vascular tree.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usingimagingasabiomarkerforasthma-170804213643/85/Using-Imaging-as-a-Biomarker-for-Asthma-13-320.jpg)