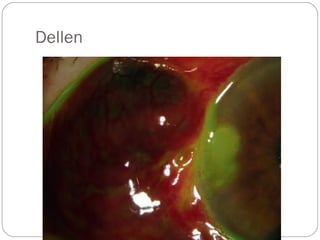

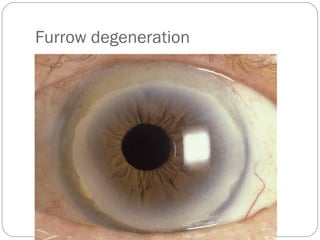

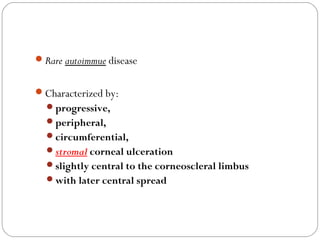

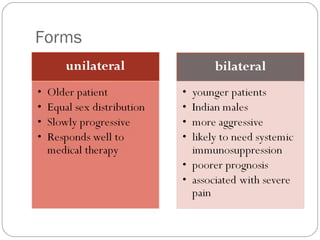

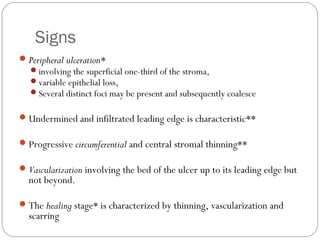

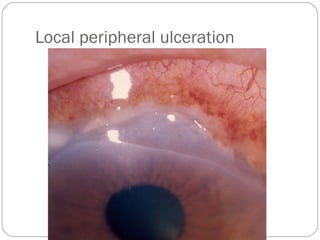

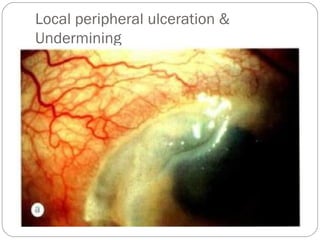

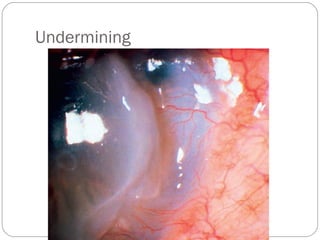

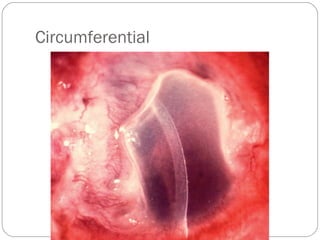

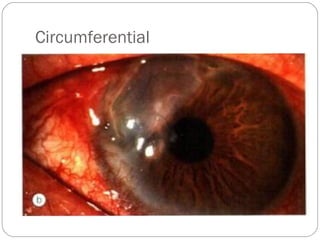

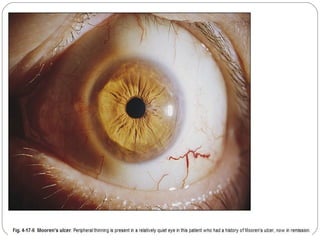

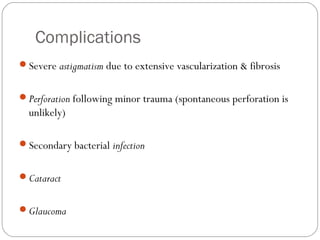

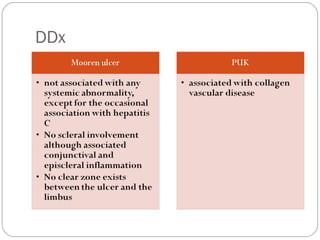

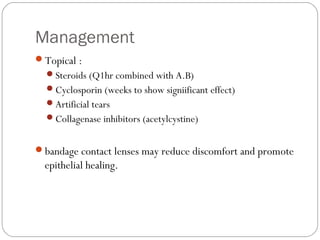

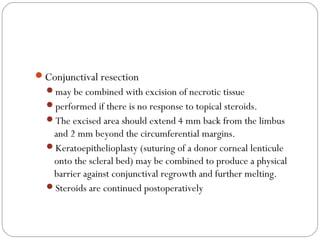

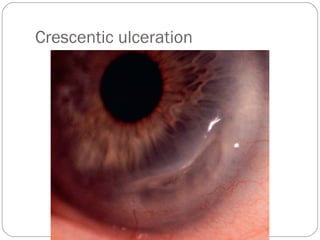

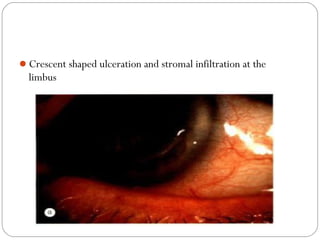

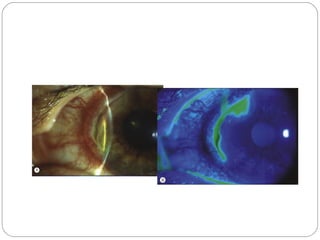

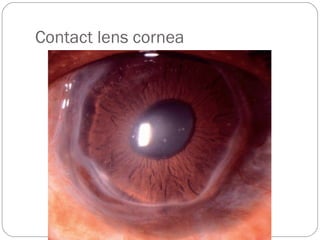

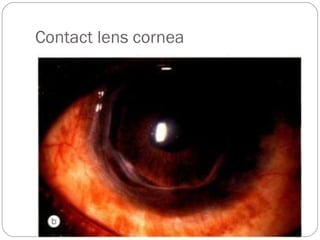

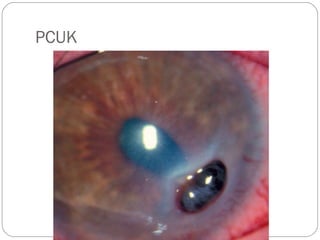

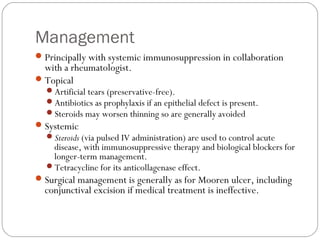

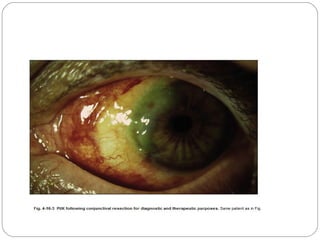

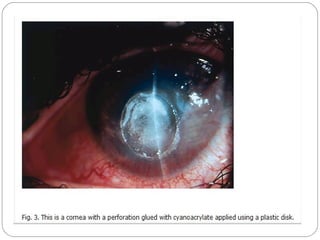

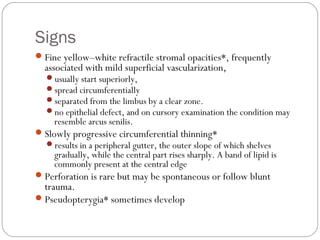

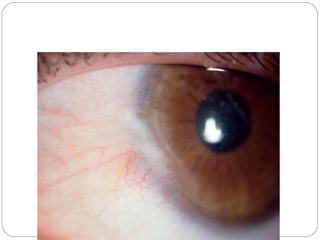

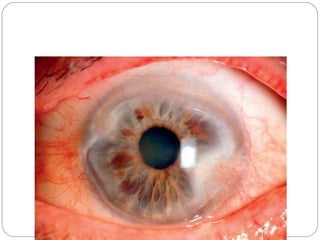

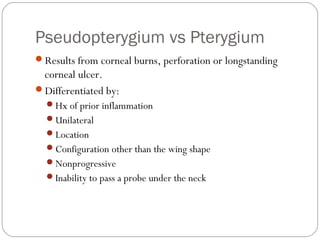

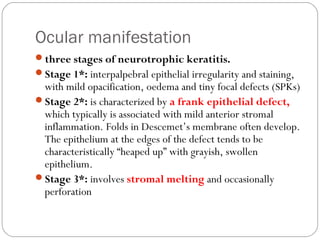

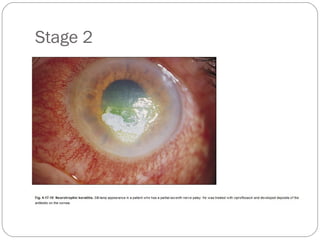

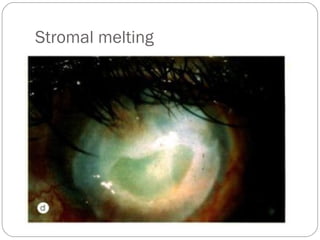

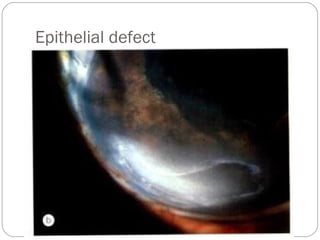

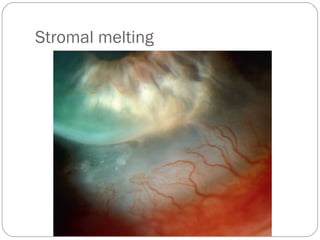

This document discusses various types of peripheral non-infectious keratitis, including Mooren ulcer, Terrien marginal degeneration, dellen, furrow degeneration, neurotrophic keratitis, and exposure keratitis. It provides details on the pathogenesis, signs and symptoms, clinical presentation, diagnostic considerations, and management approaches for each condition. The conditions are characterized by thinning and/or ulceration preferentially affecting the peripheral rather than the central cornea. Management involves identifying and treating underlying causes, using lubricants, bandage contact lenses, amniotic membrane grafts, tarsorrhaphy, and in some cases immunosuppression or surgery.