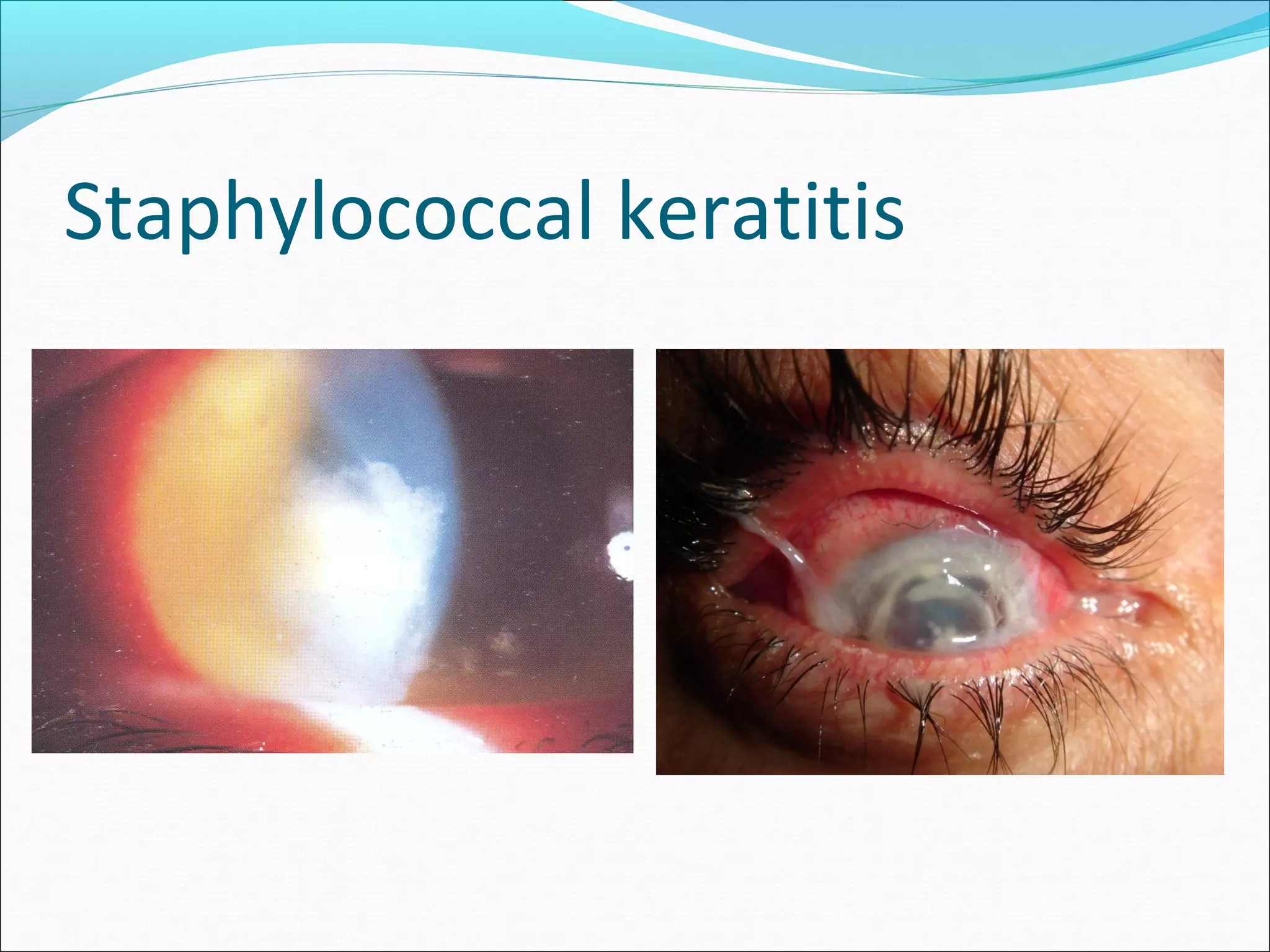

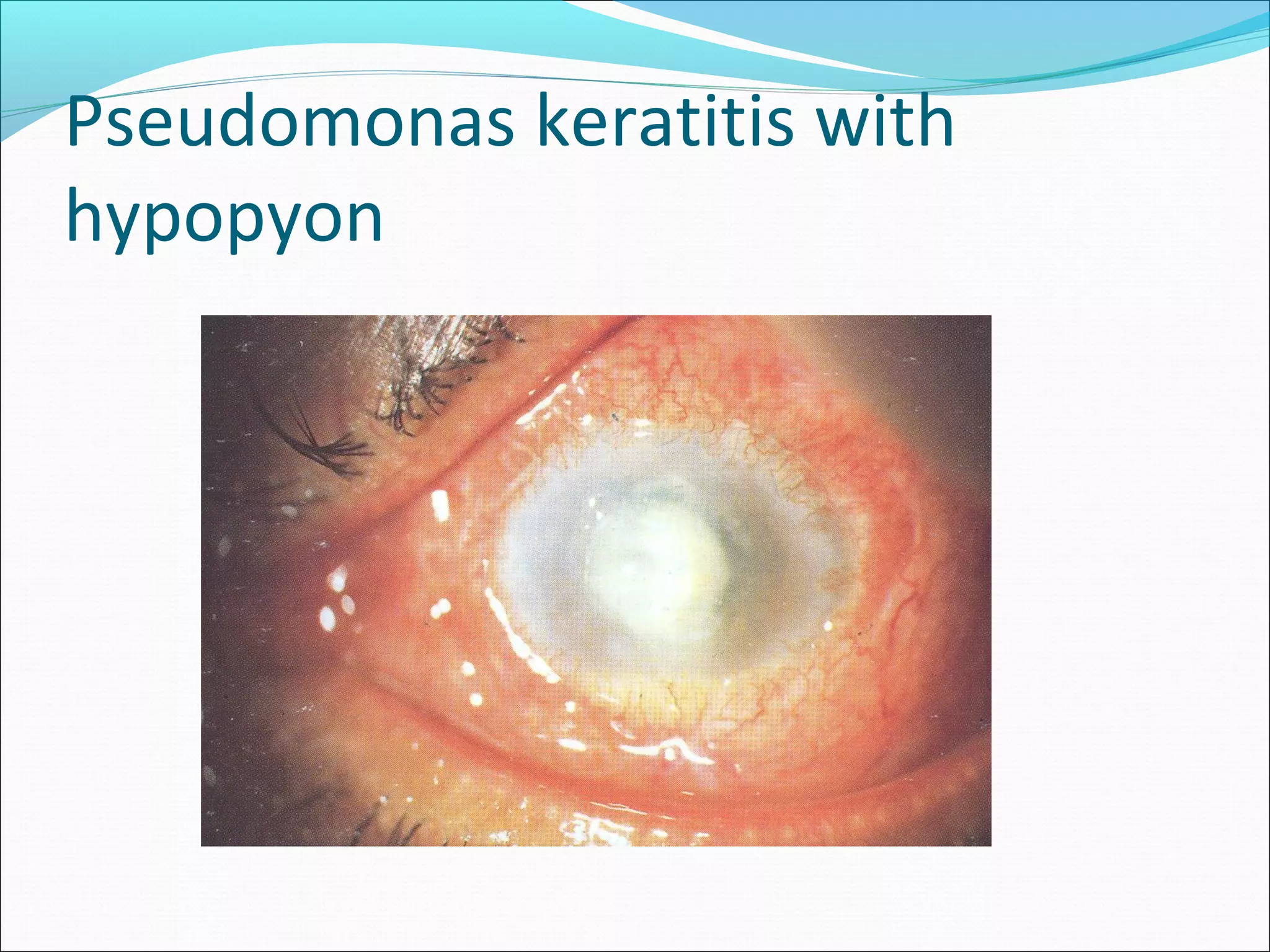

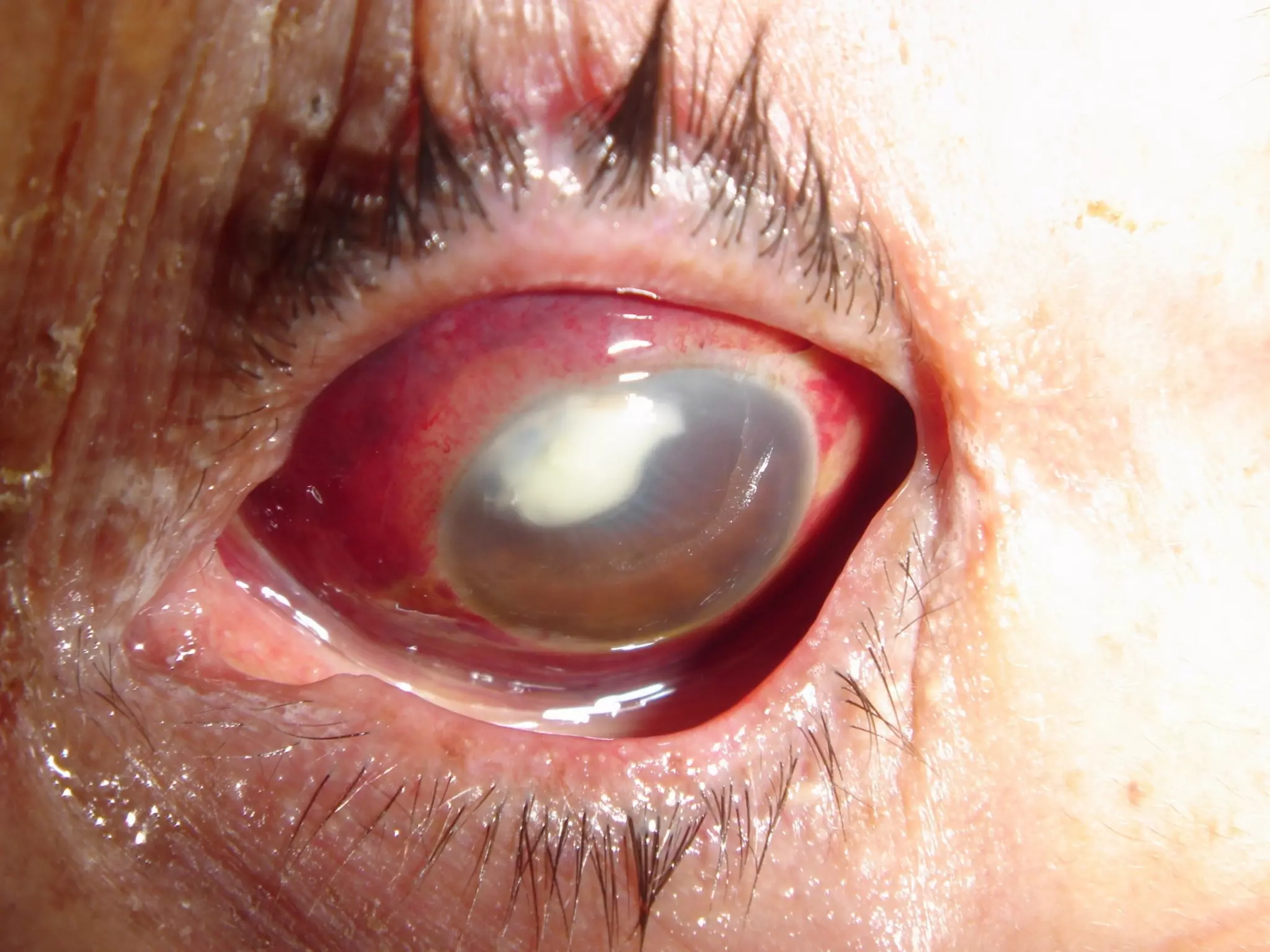

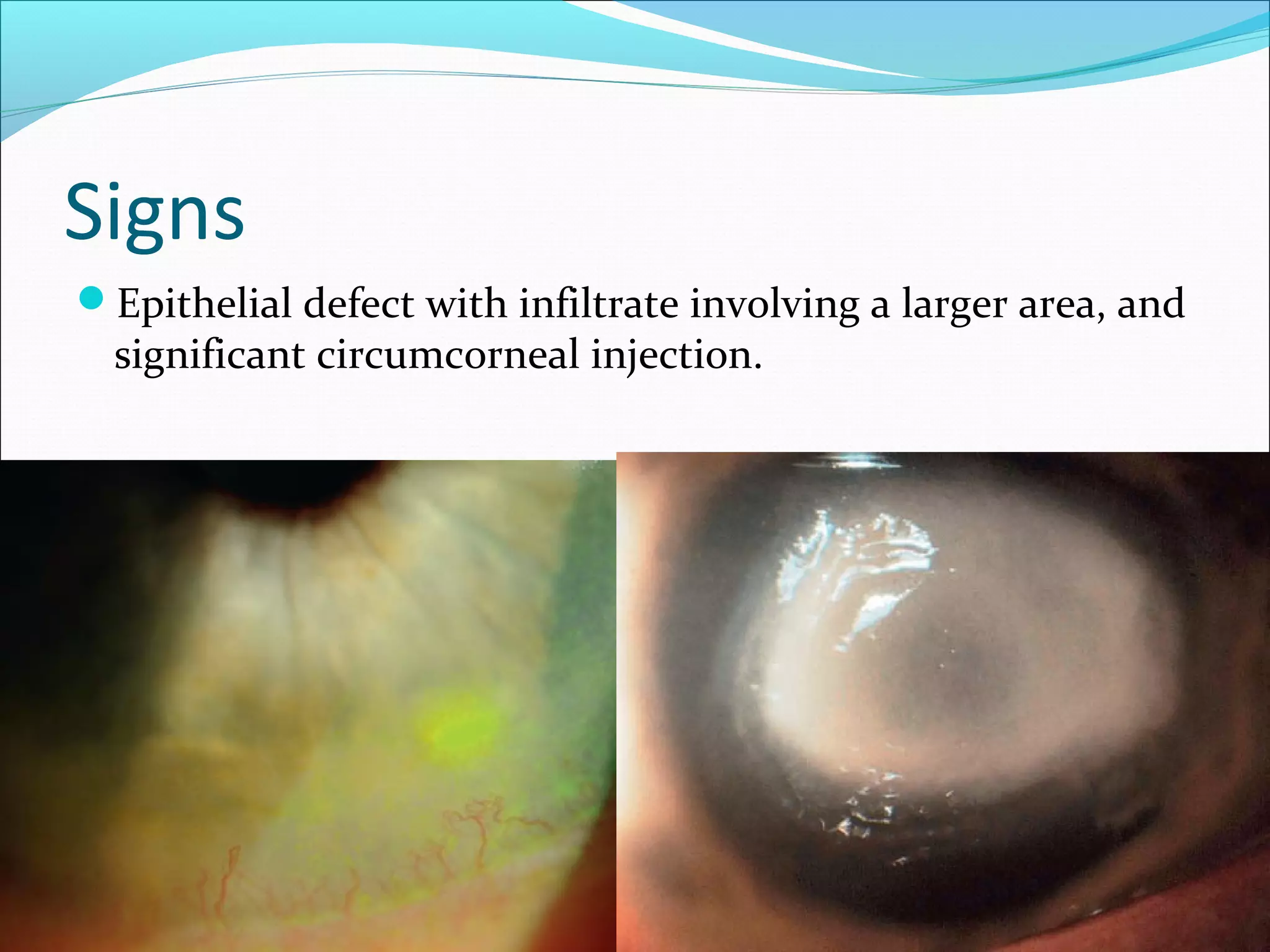

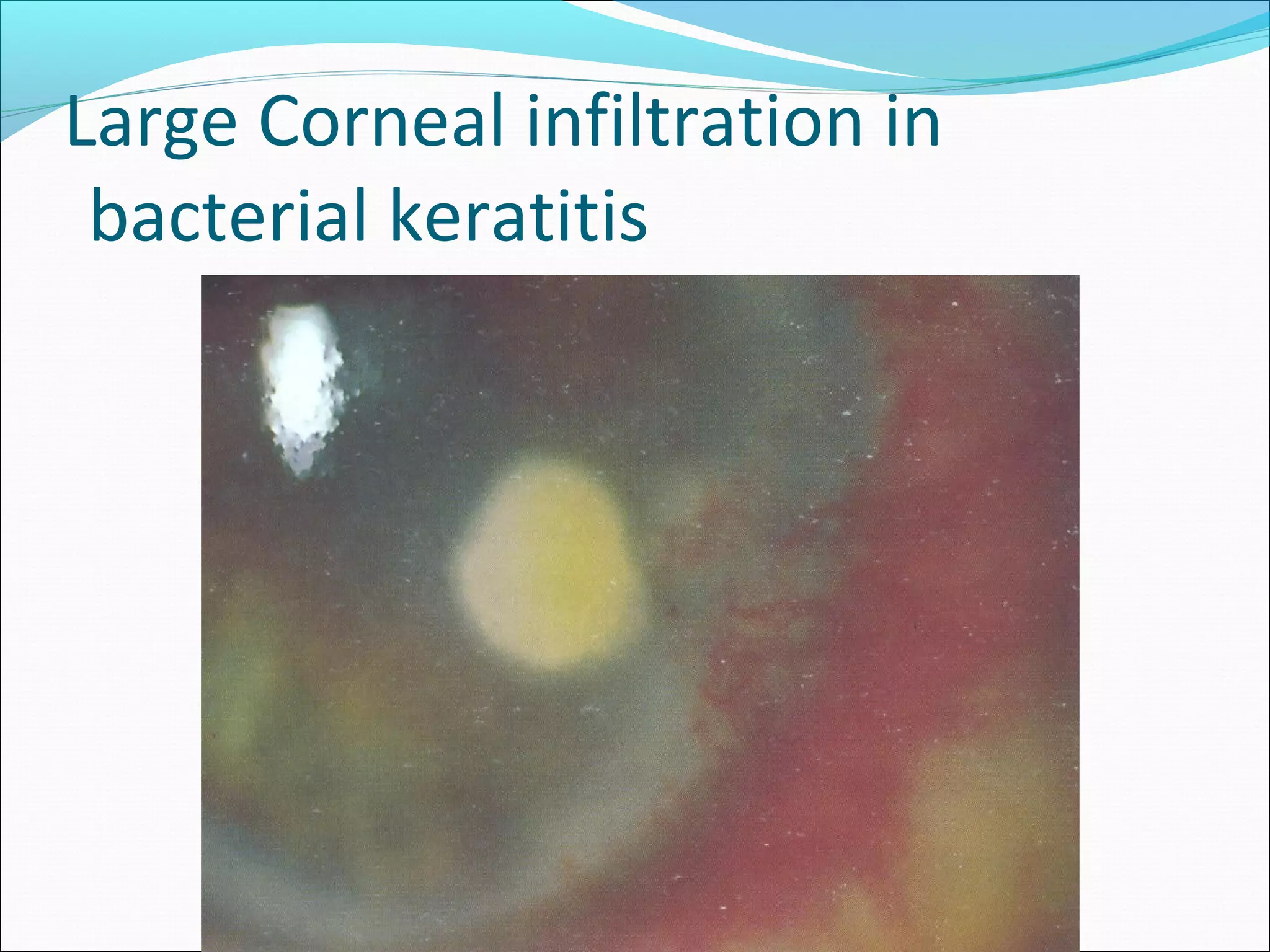

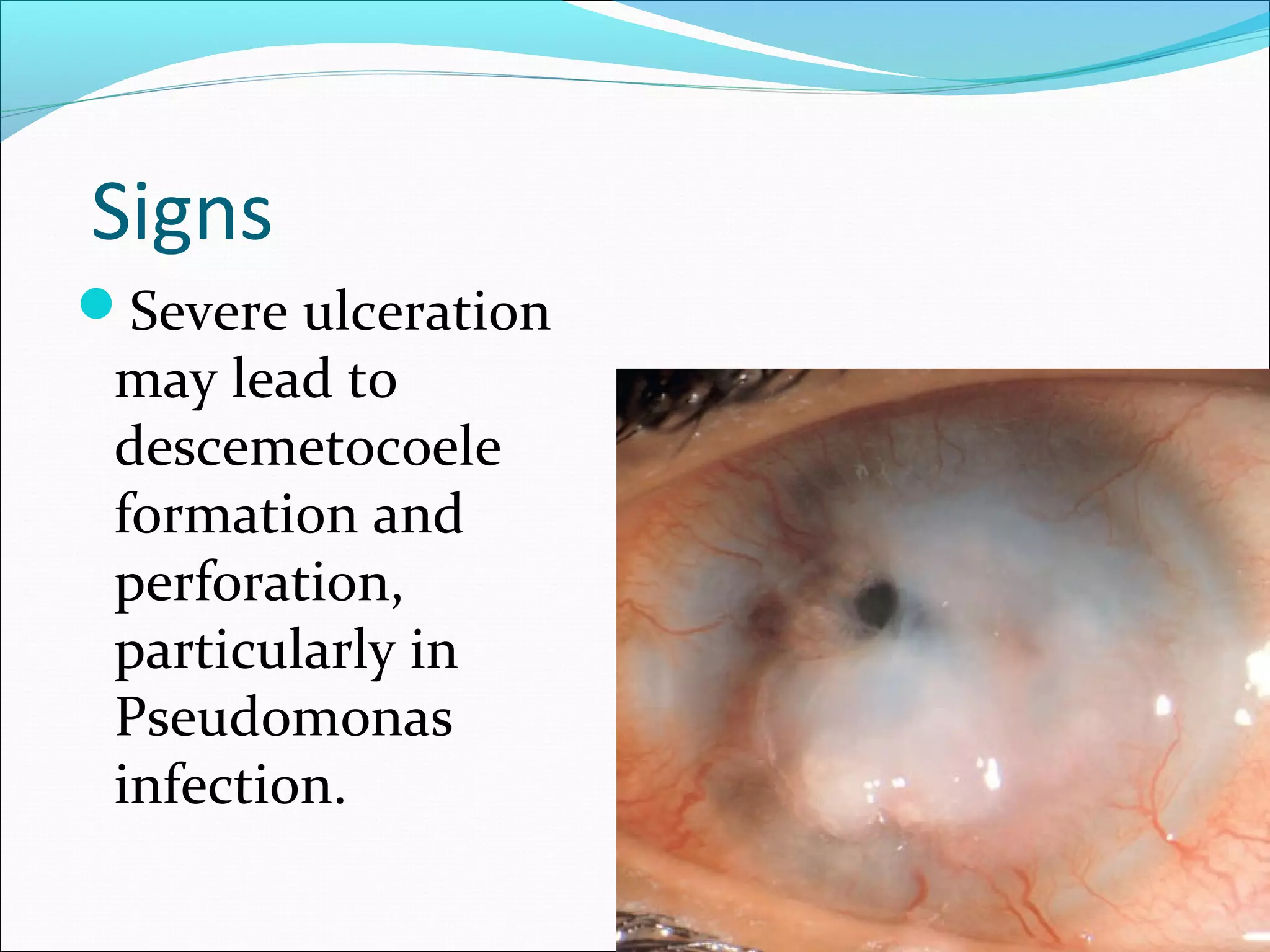

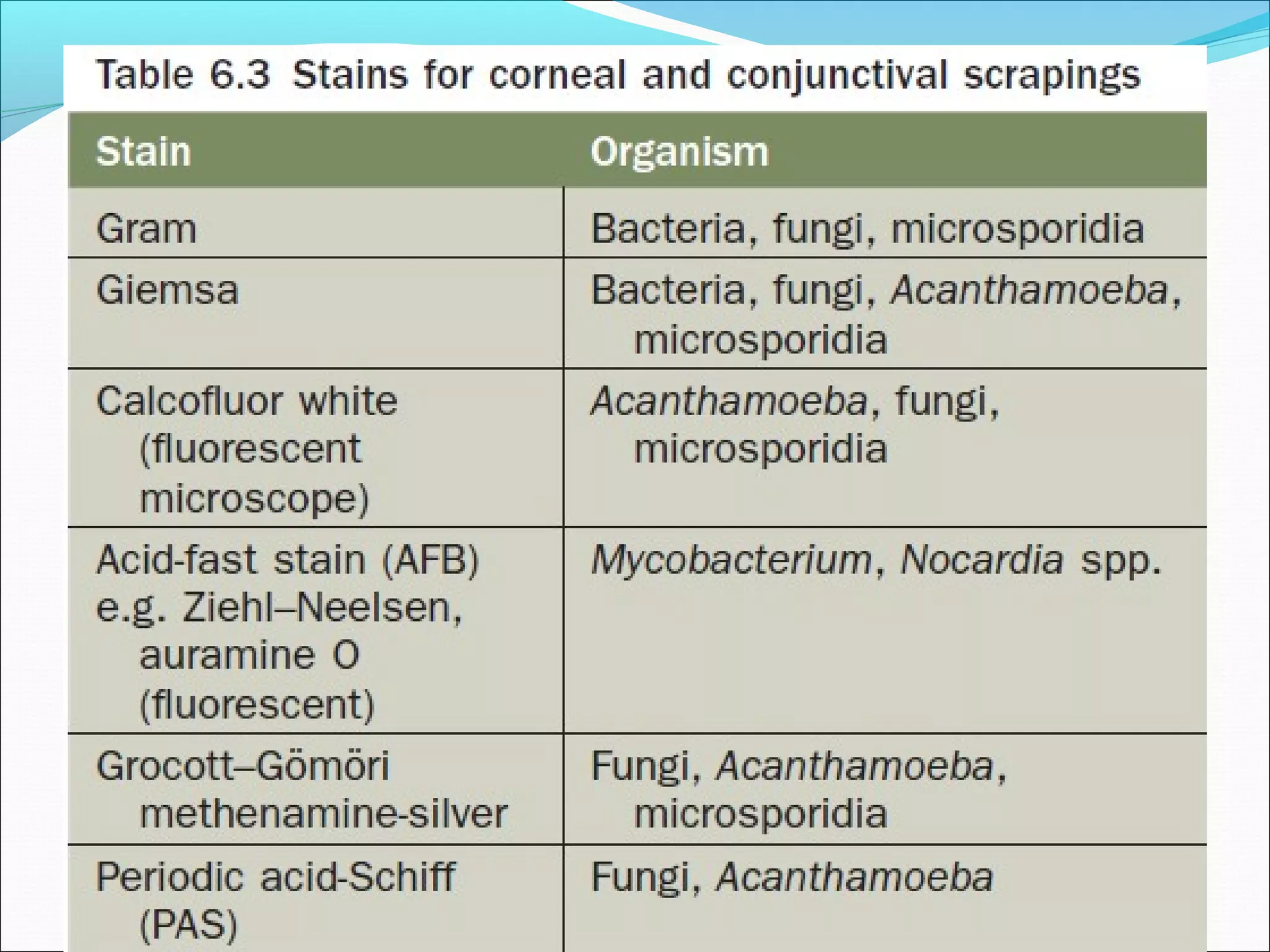

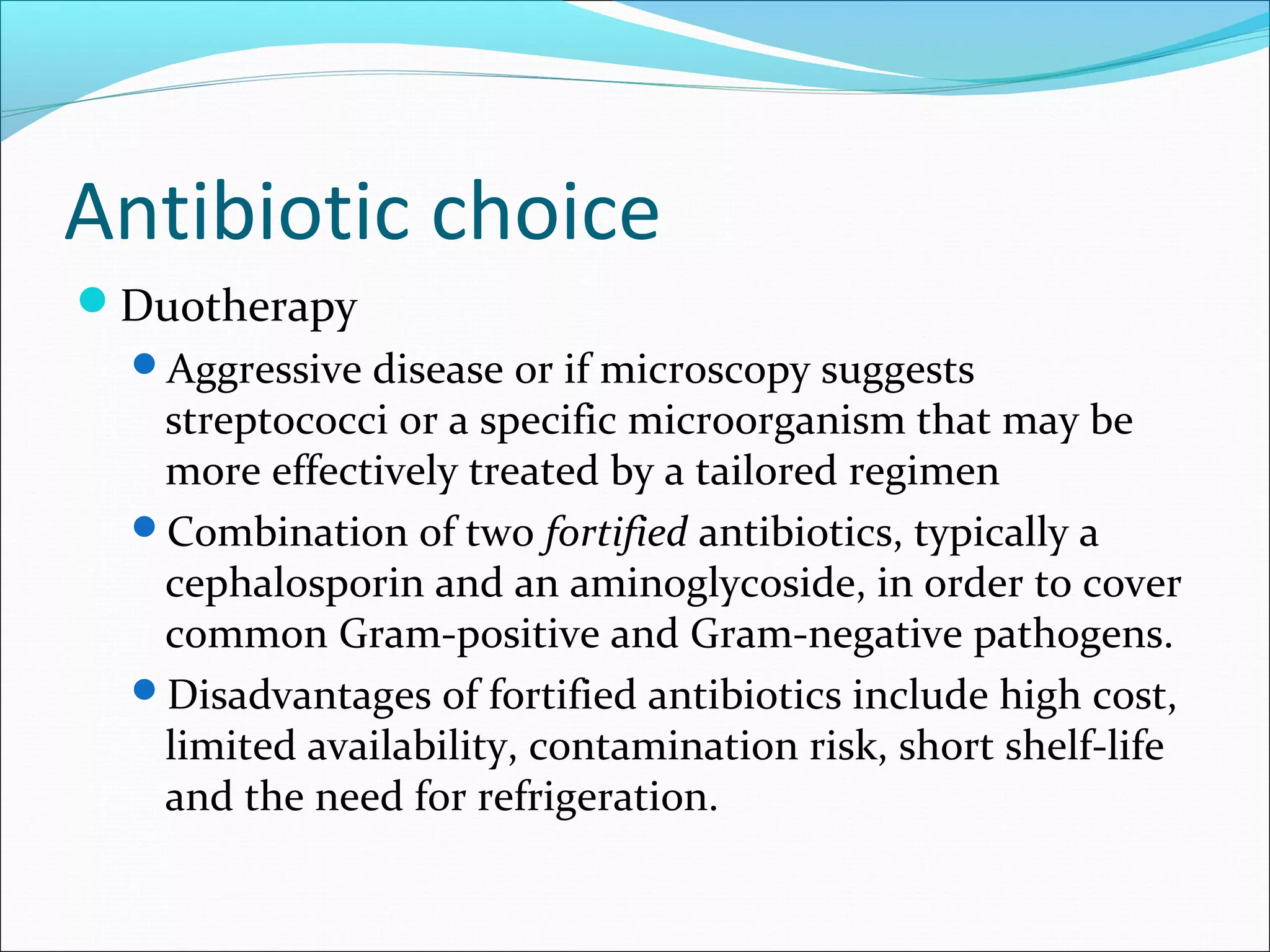

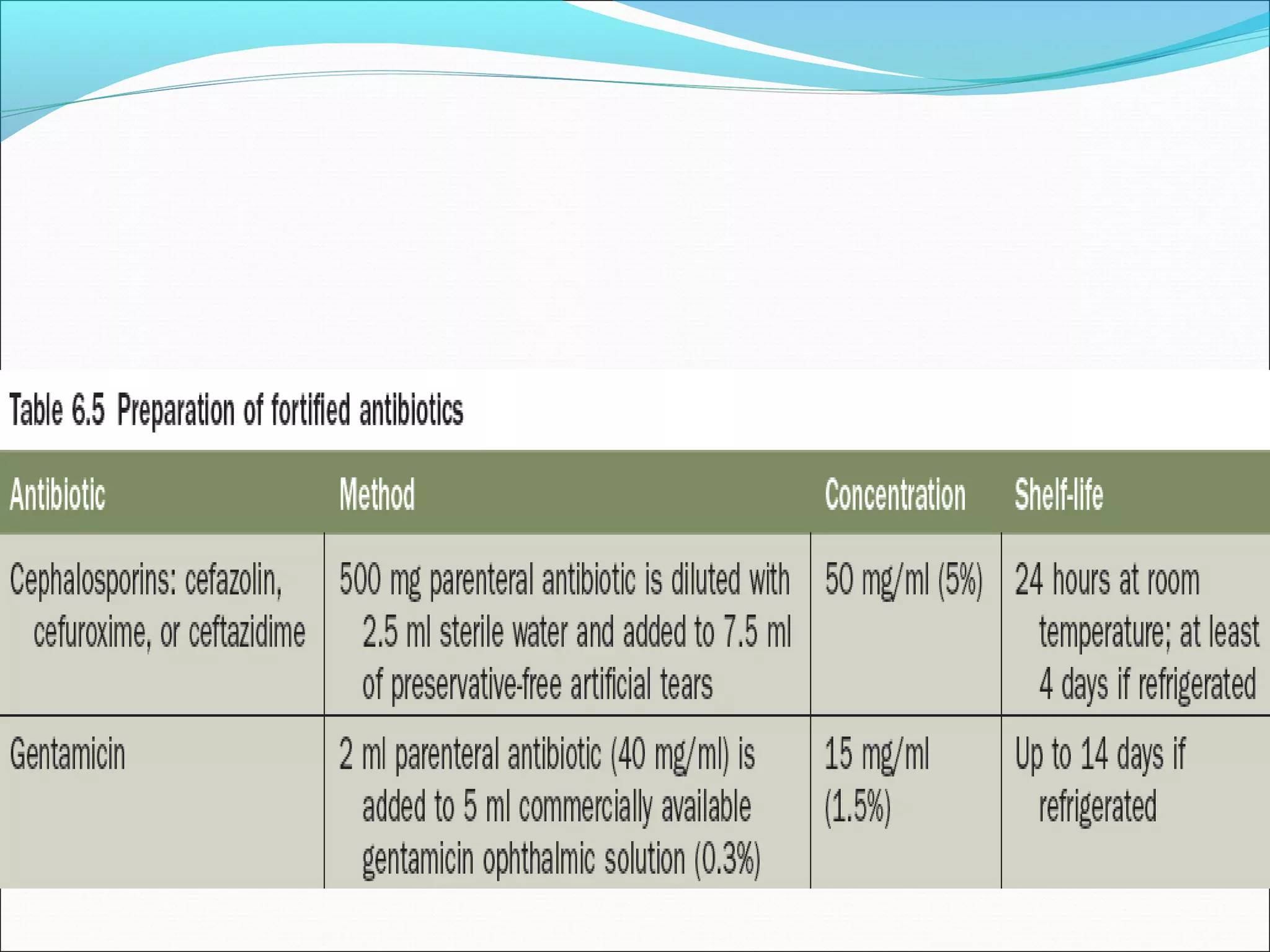

This document discusses bacterial keratitis, including common pathogens, risk factors, symptoms, signs, investigations, management, and visual rehabilitation. It notes that Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus are common causes. Risk factors include contact lens wear and ocular surface disease. Treatment involves topical antibiotics, with fluoroquinolones or combination therapy used. Steroids may be added after initial antibiotic treatment but are avoided if thinning/perforation occur. Systemic antibiotics are used if systemic involvement is possible. Surgical intervention like patching or keratoplasty may be needed for perforations or dense scarring.