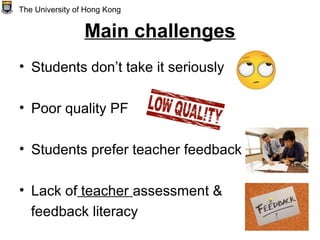

David Carless gave a presentation on implementing peer feedback in educational settings. He discussed the potential benefits of peer feedback, including generating dialogue around student work and helping students reflect on their own performance. However, he also noted several challenges, such as students not taking peer feedback seriously or providing feedback of poor quality. Carless emphasized the importance of preparing students for peer feedback through modeling, guidance on criteria, and building trust between students.