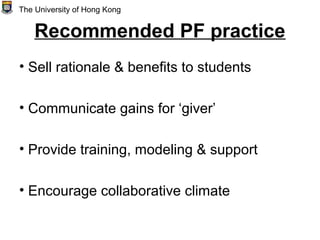

The document summarizes a talk on designing and implementing collaborative assessment. It discusses having student input on assessment design and implementation to increase engagement. Peer feedback is a key part of collaborative assessment where students provide feedback to each other. Research shows students benefit more from giving peer feedback than receiving it. Challenges to peer feedback include students not taking it seriously and poor quality feedback. Training, modeling, and guidance from teachers can help address these challenges and improve peer feedback practices.