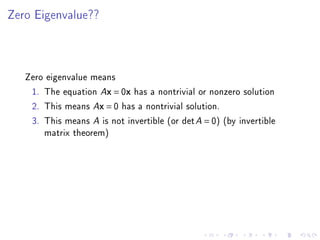

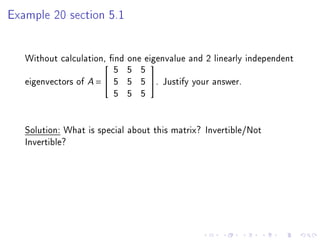

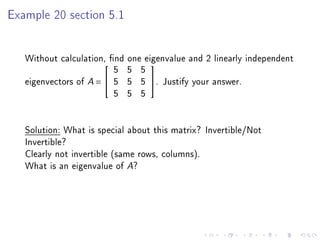

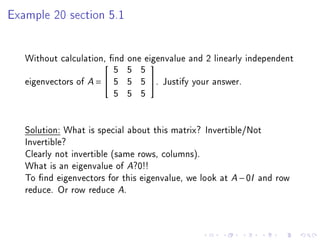

1. The matrix is not invertible as it has repeated rows.

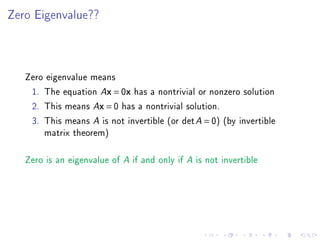

2. The eigenvalue is 0 since a matrix is not invertible if it has 0 as an eigenvalue.

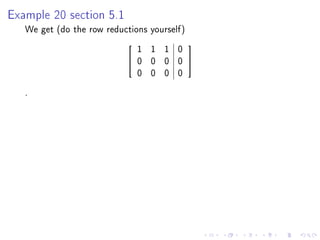

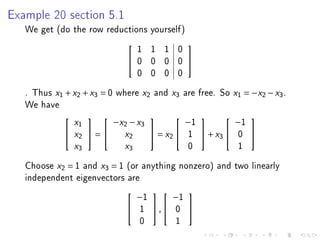

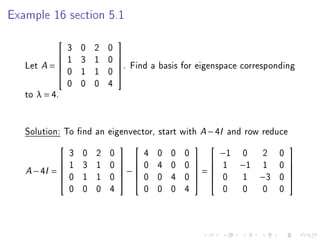

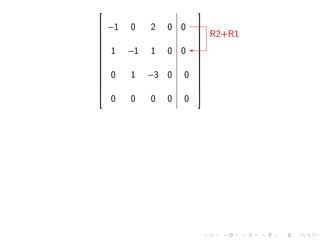

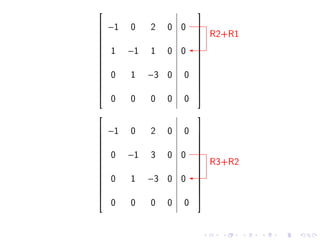

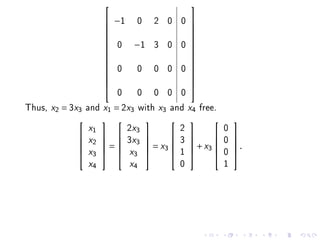

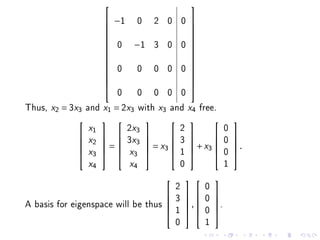

3. The eigenvectors corresponding to 0 can be found by reducing the matrix A - 0I to row echelon form. This gives the equation x1 + x2 + x3 = 0 with x2 and x3 as free variables, so two linearly independent eigenvectors are (1, -1, 0) and (1, 0, -1).