- Quiz 4 will be tomorrow covering sections 3.3, 5.1, and 5.2 of the textbook. It will include 3 problems on Cramer's rule, finding eigenvectors given eigenvalues, and finding characteristic polynomials/eigenvalues of 2x2 and 3x3 matrices. Students must show all work.

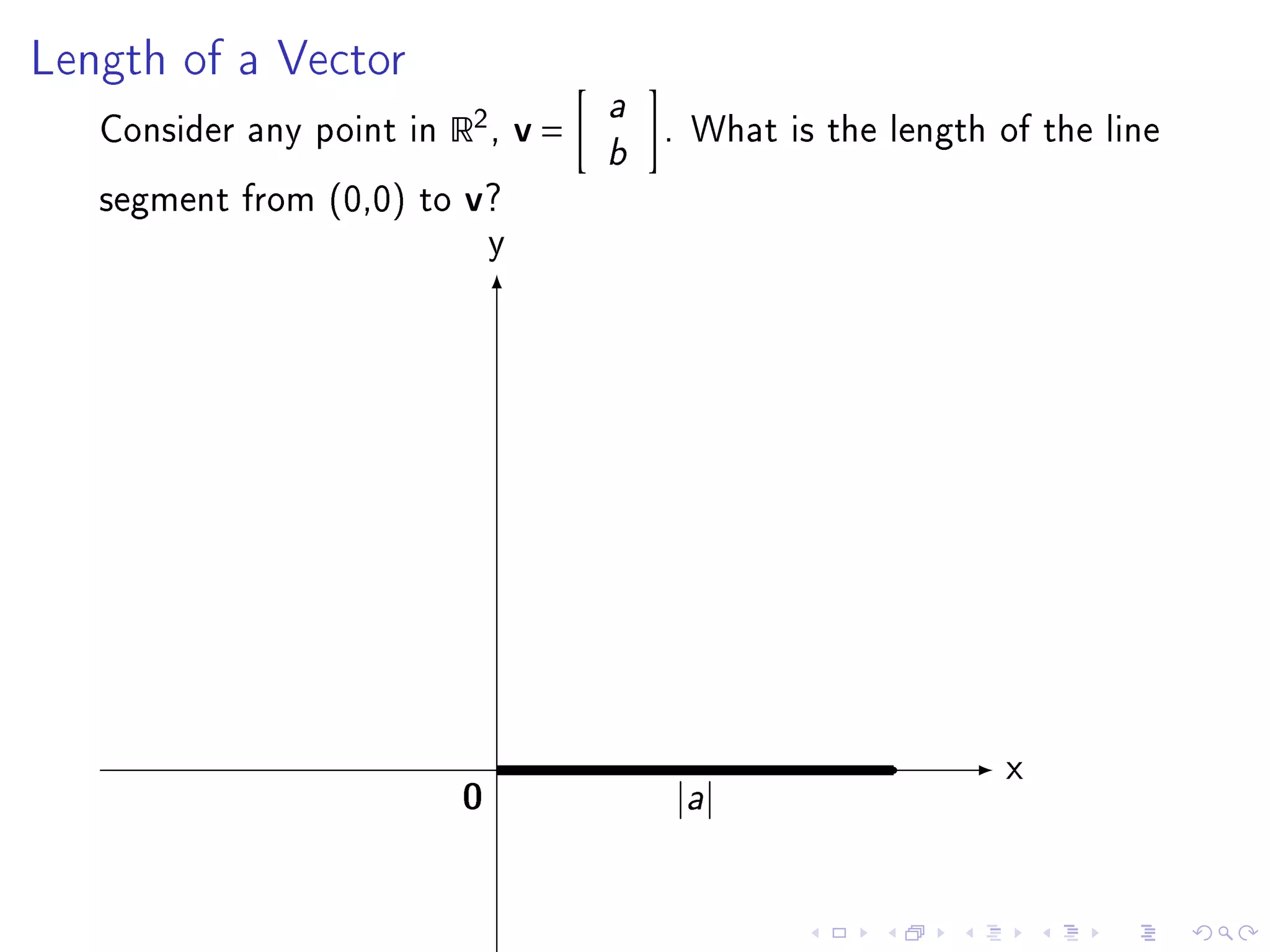

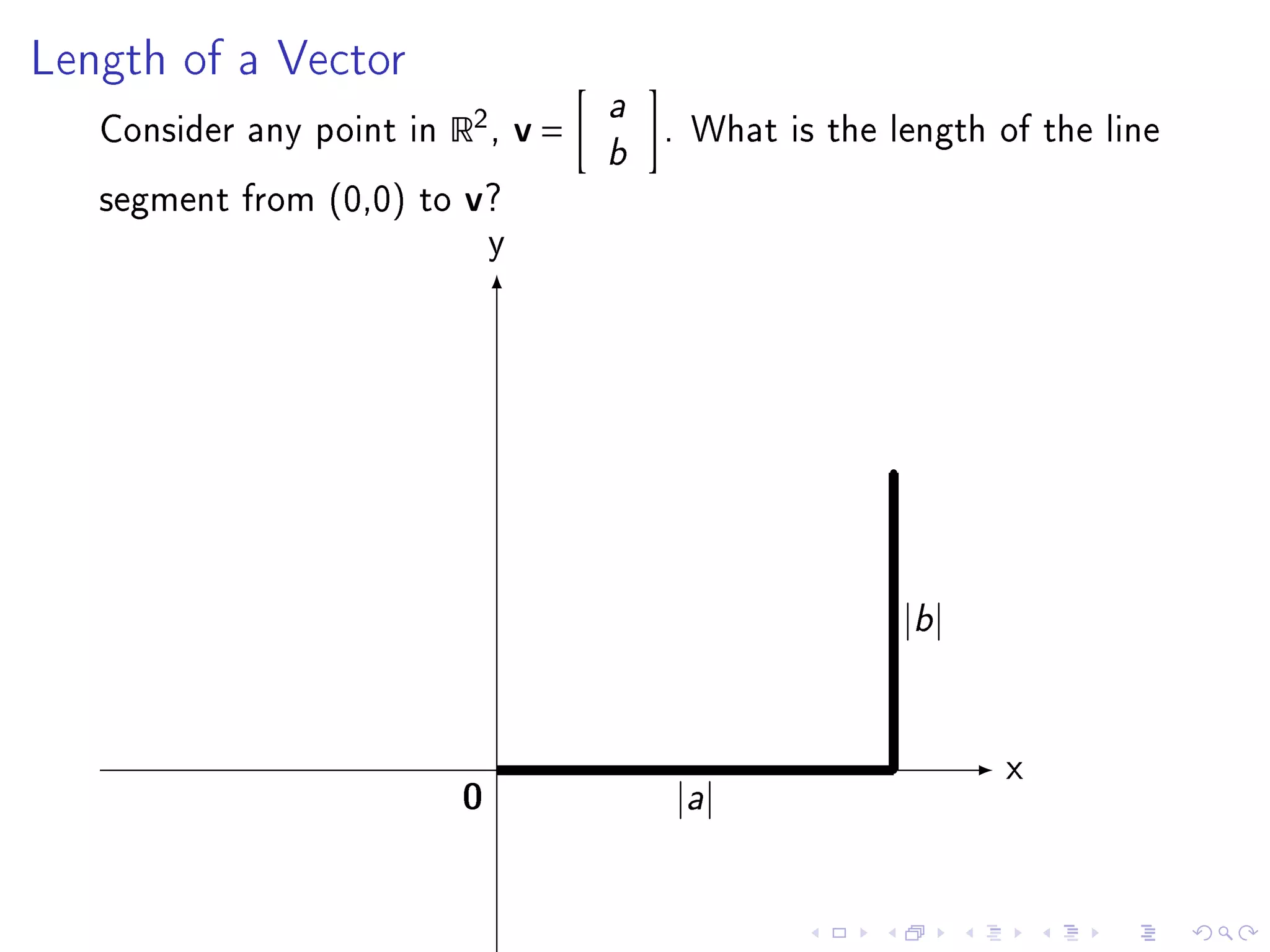

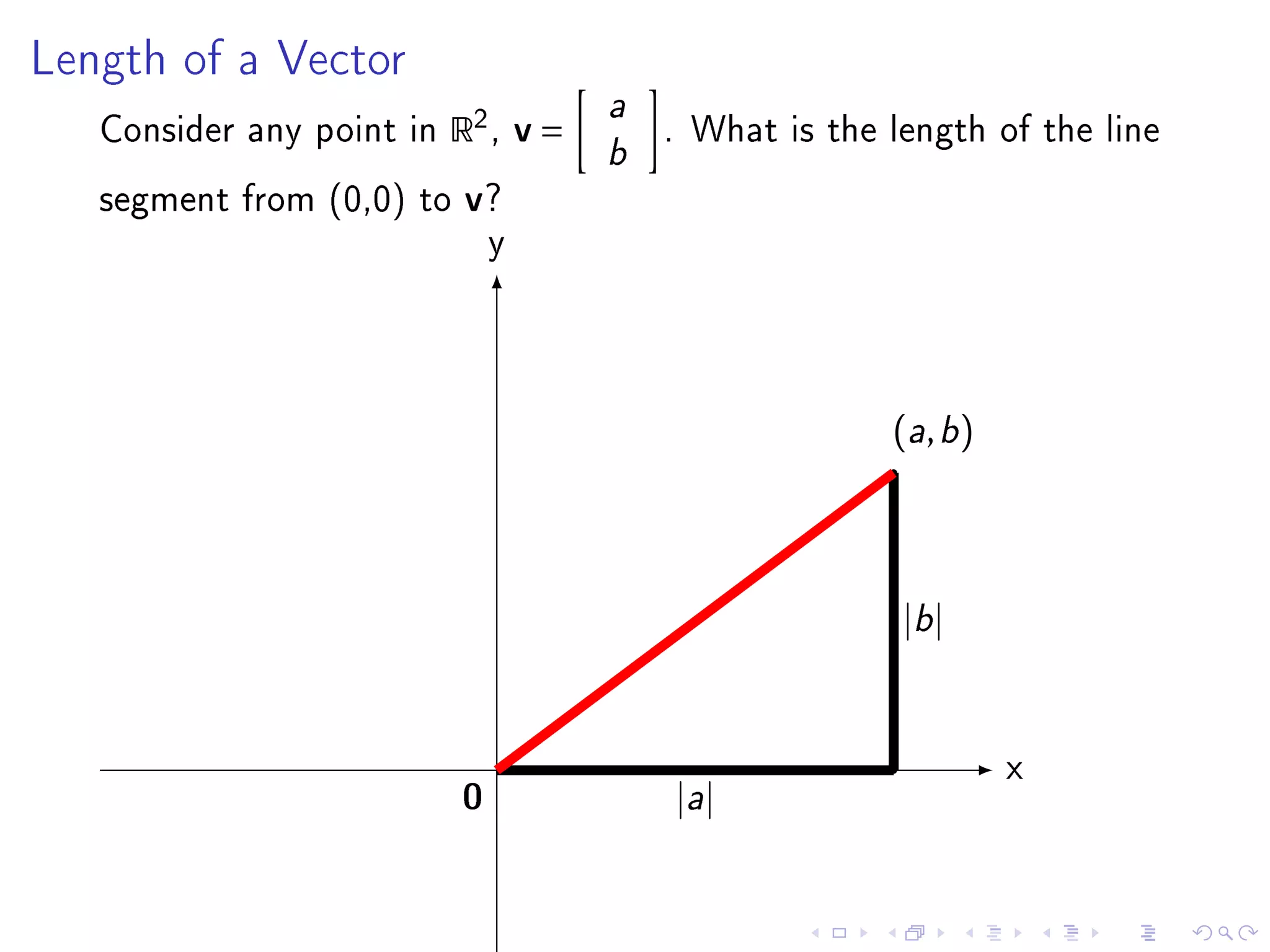

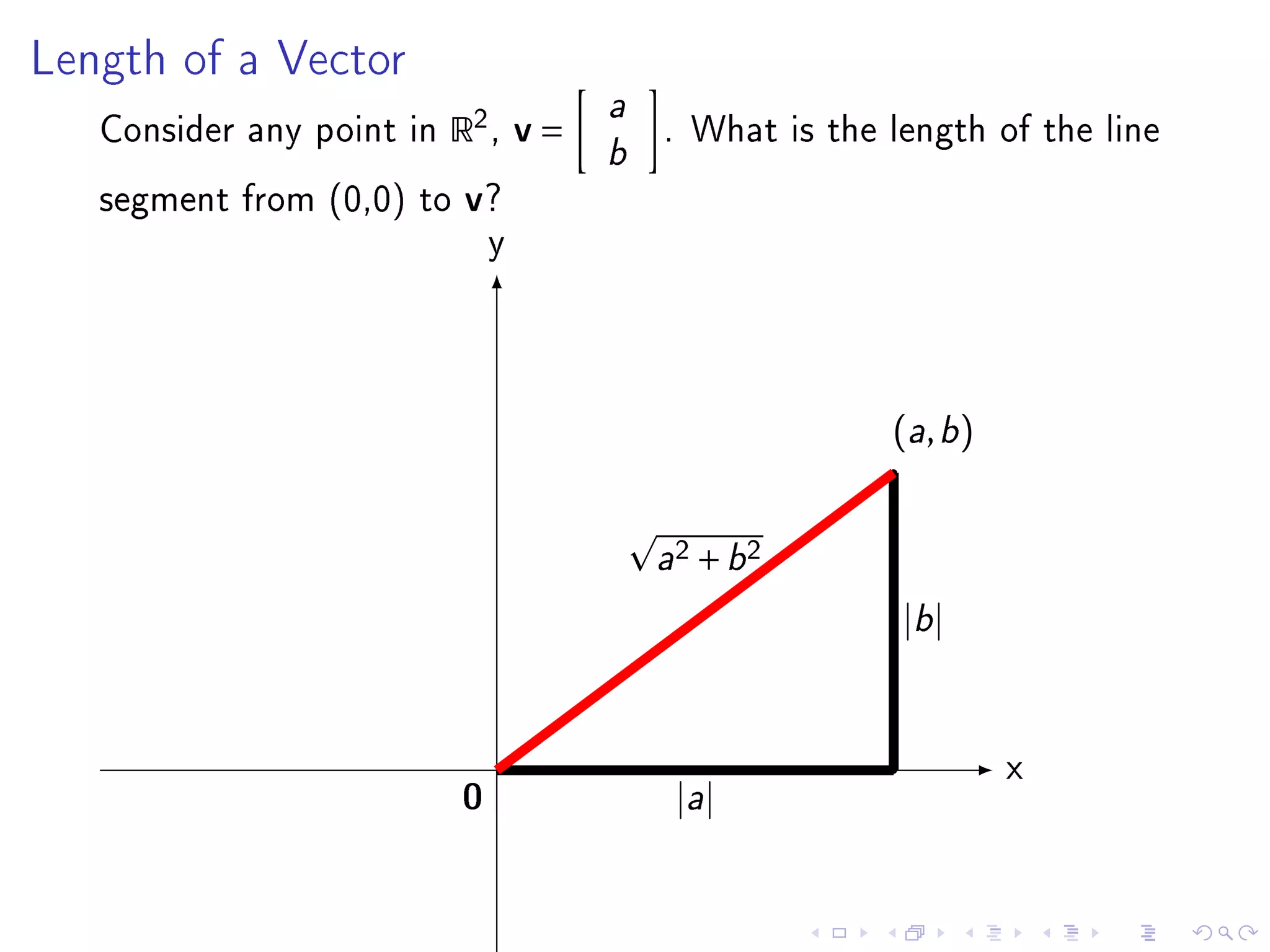

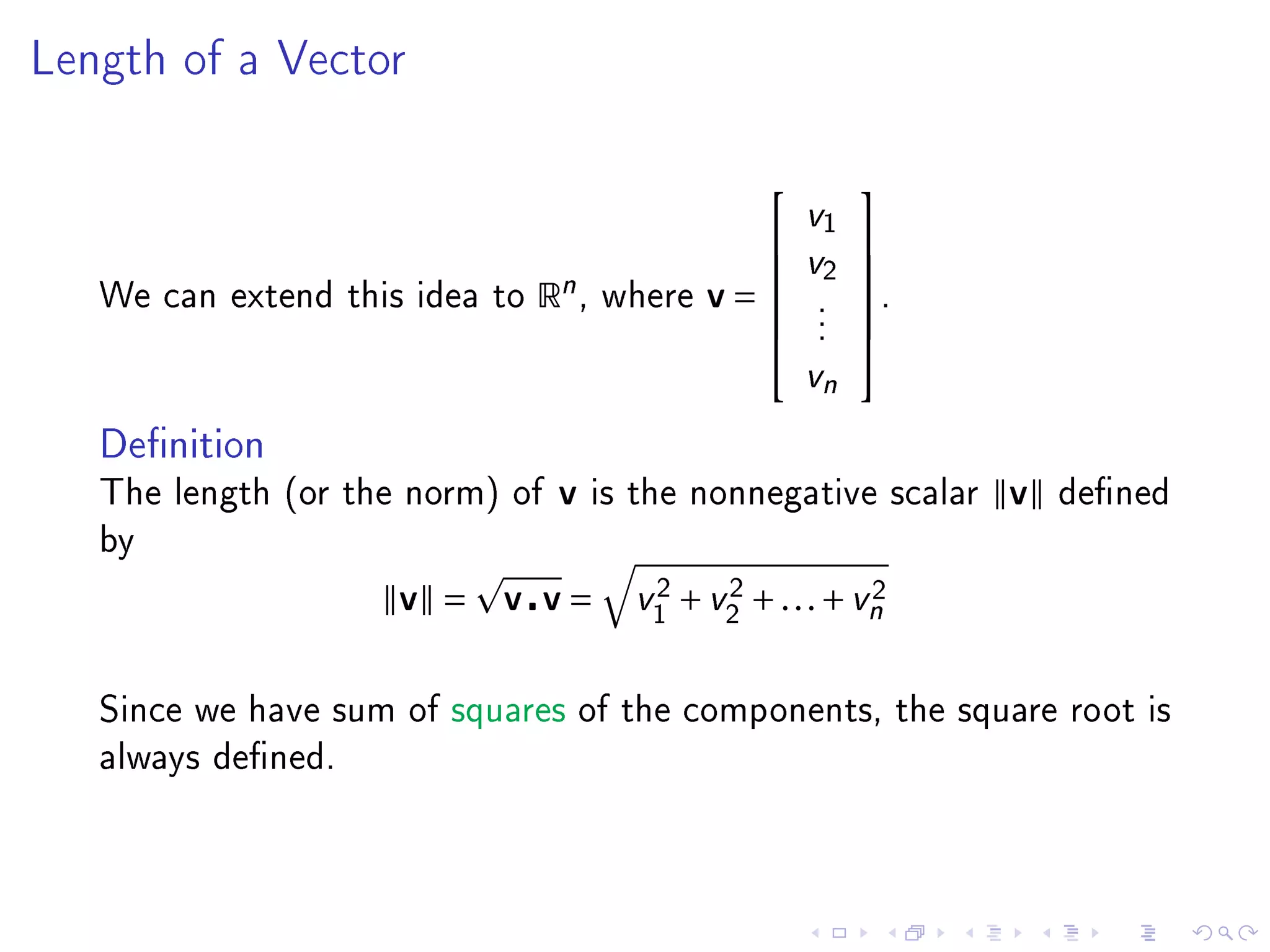

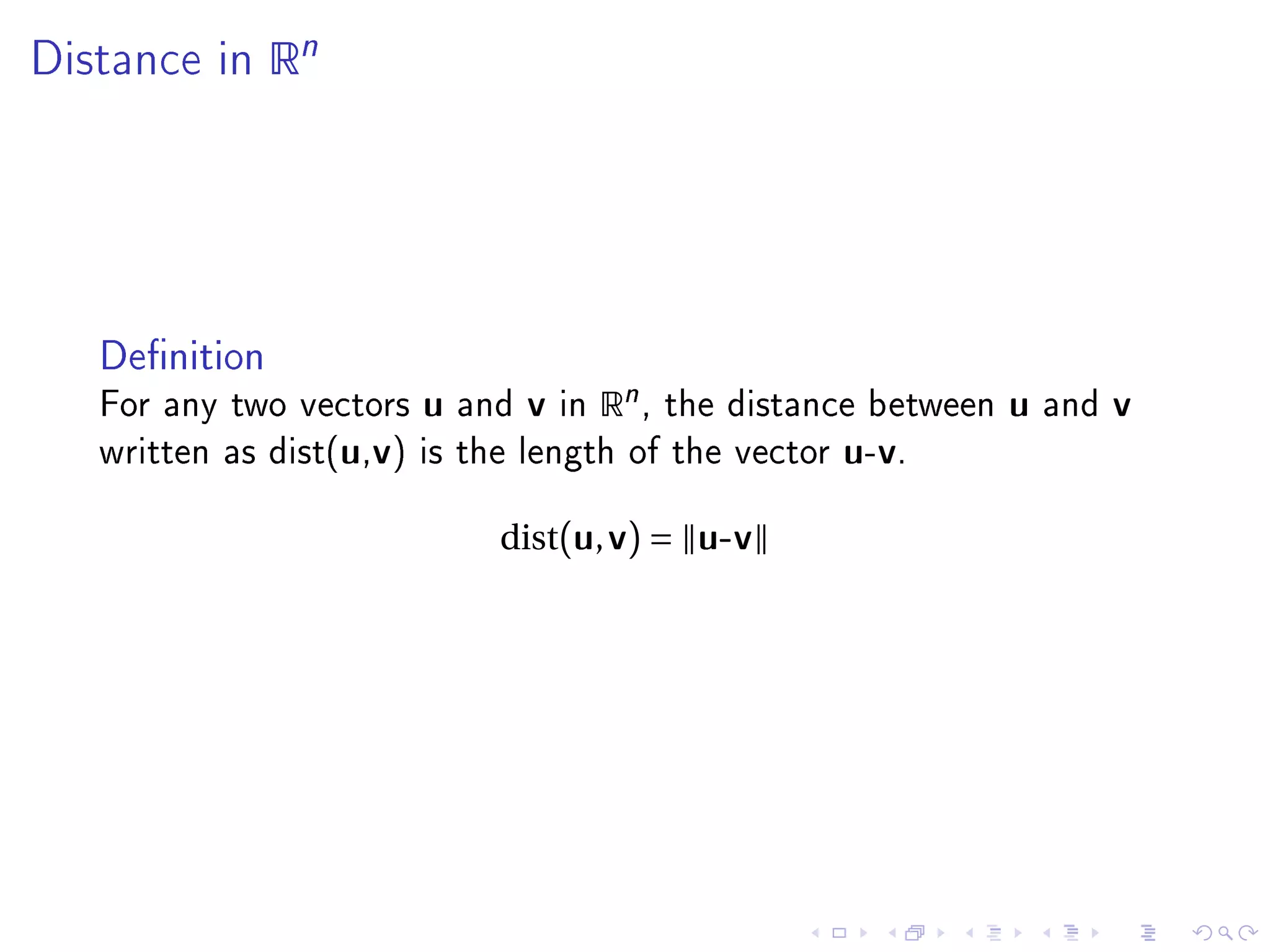

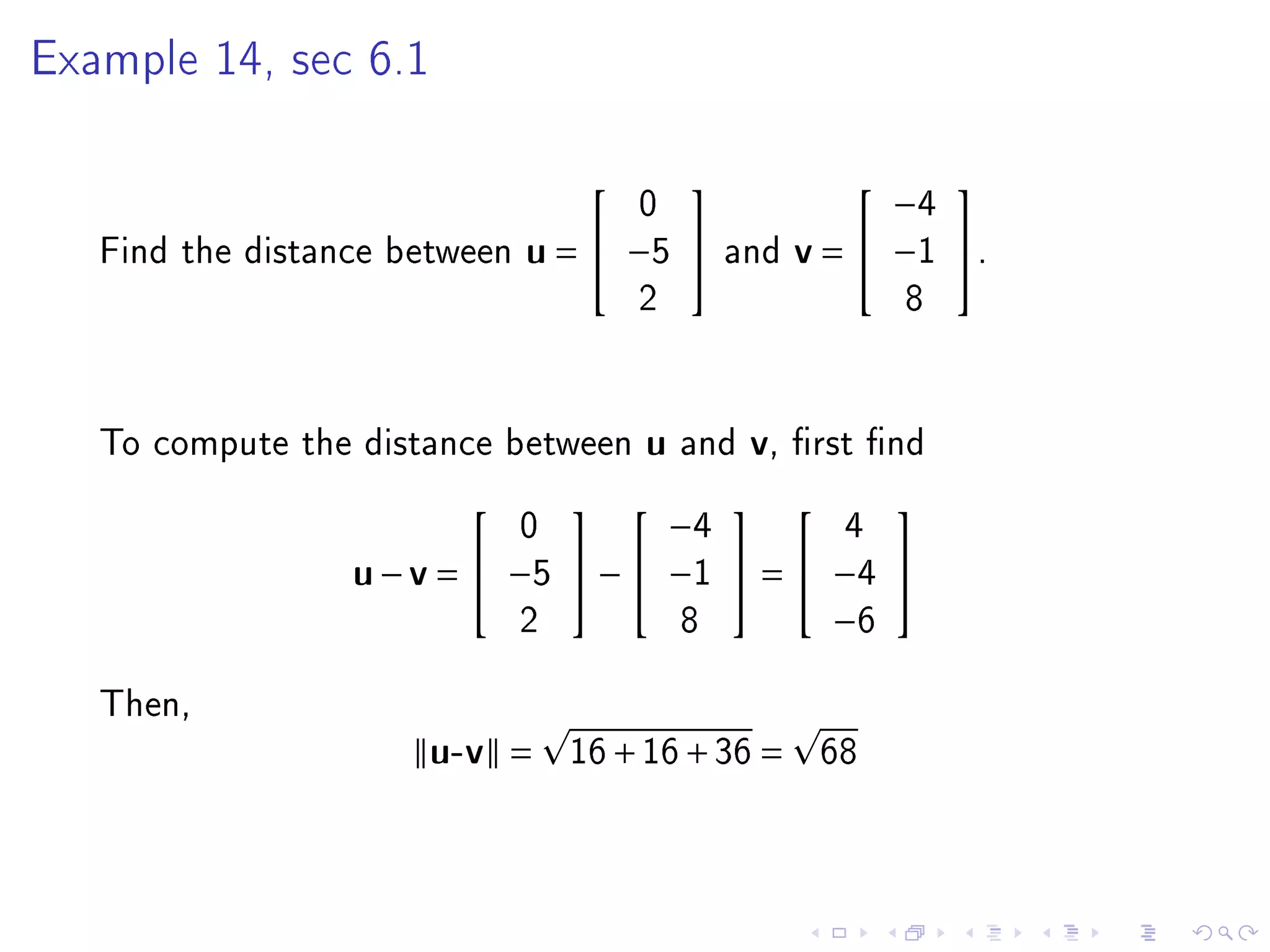

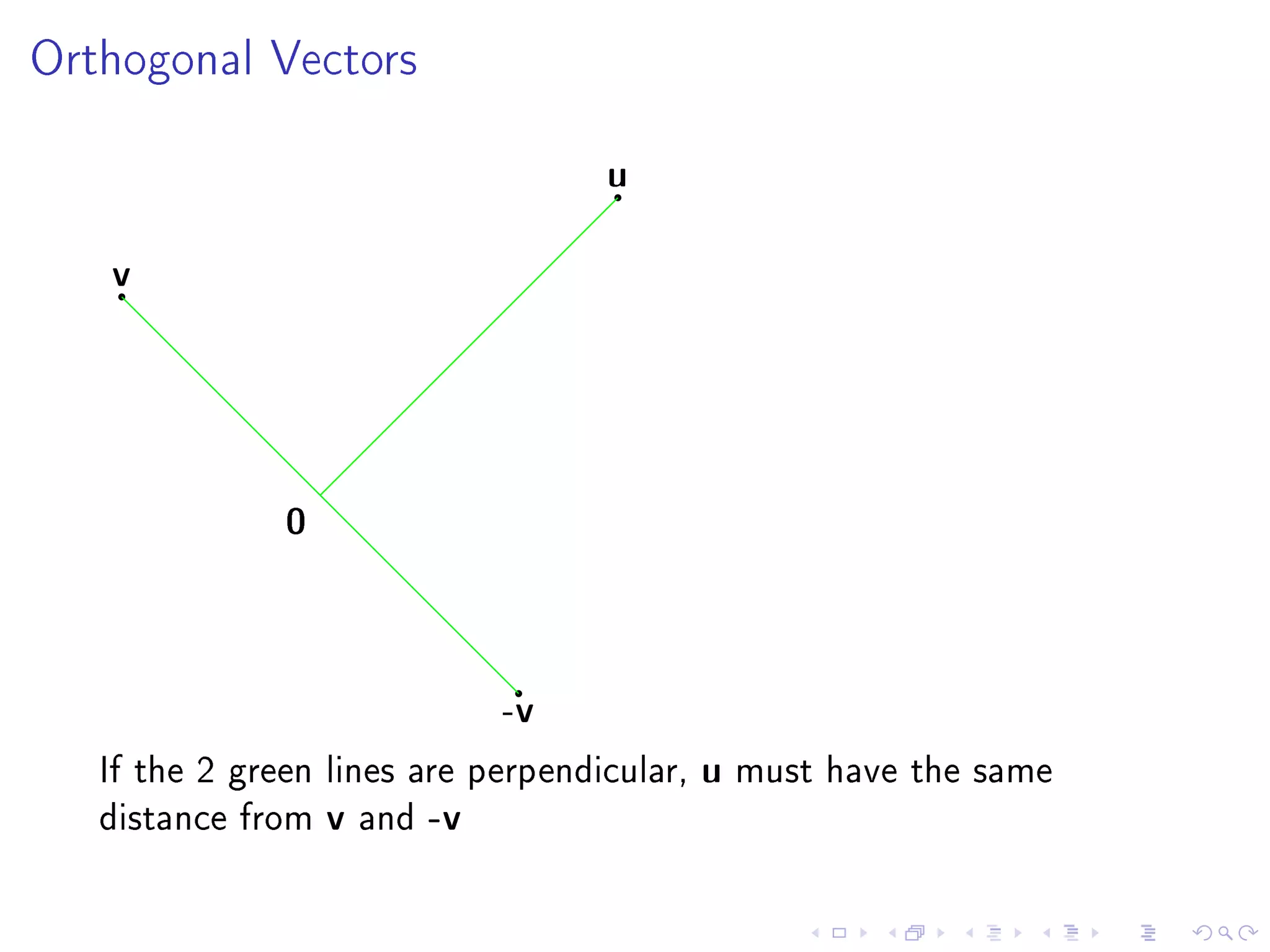

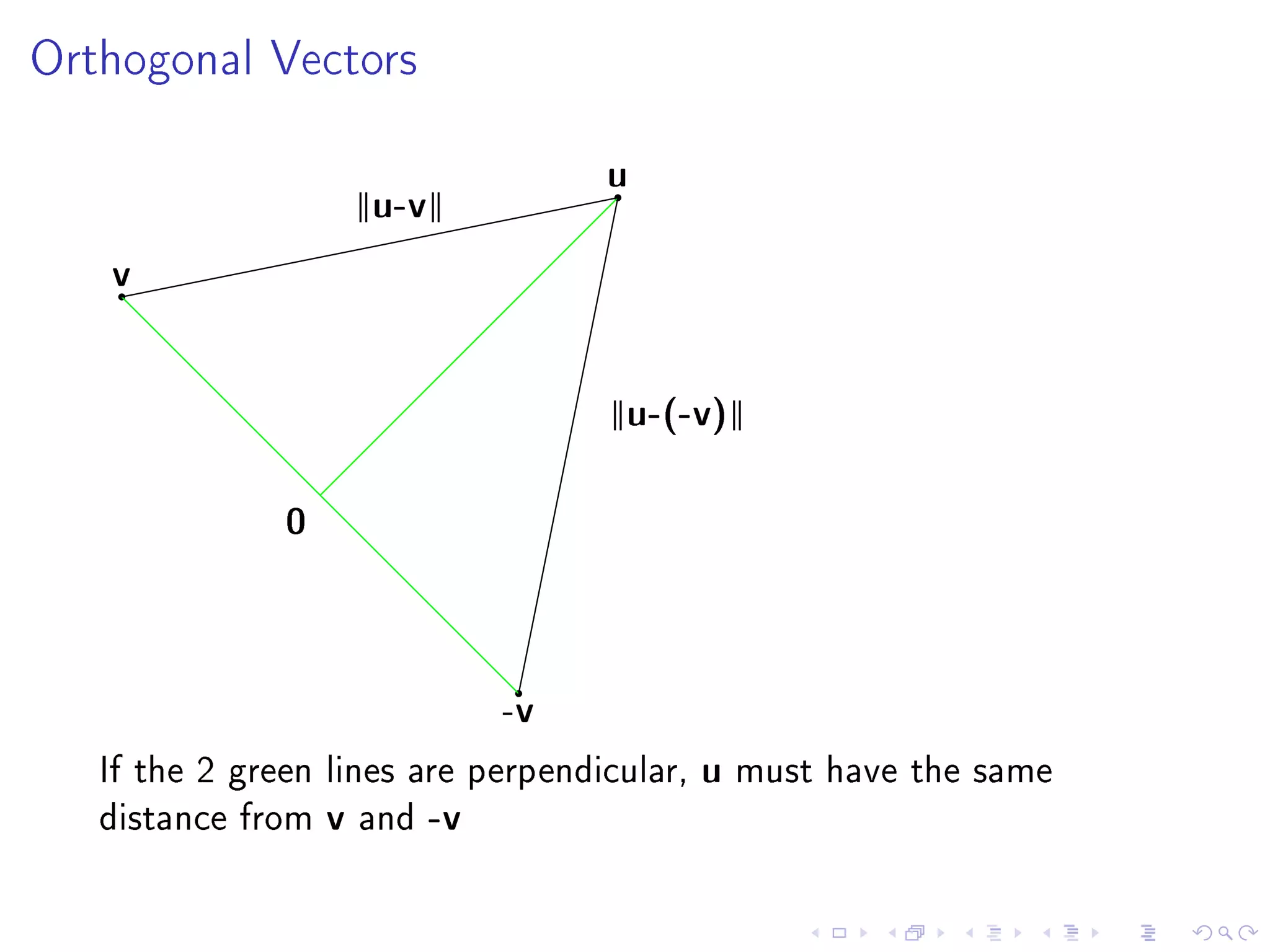

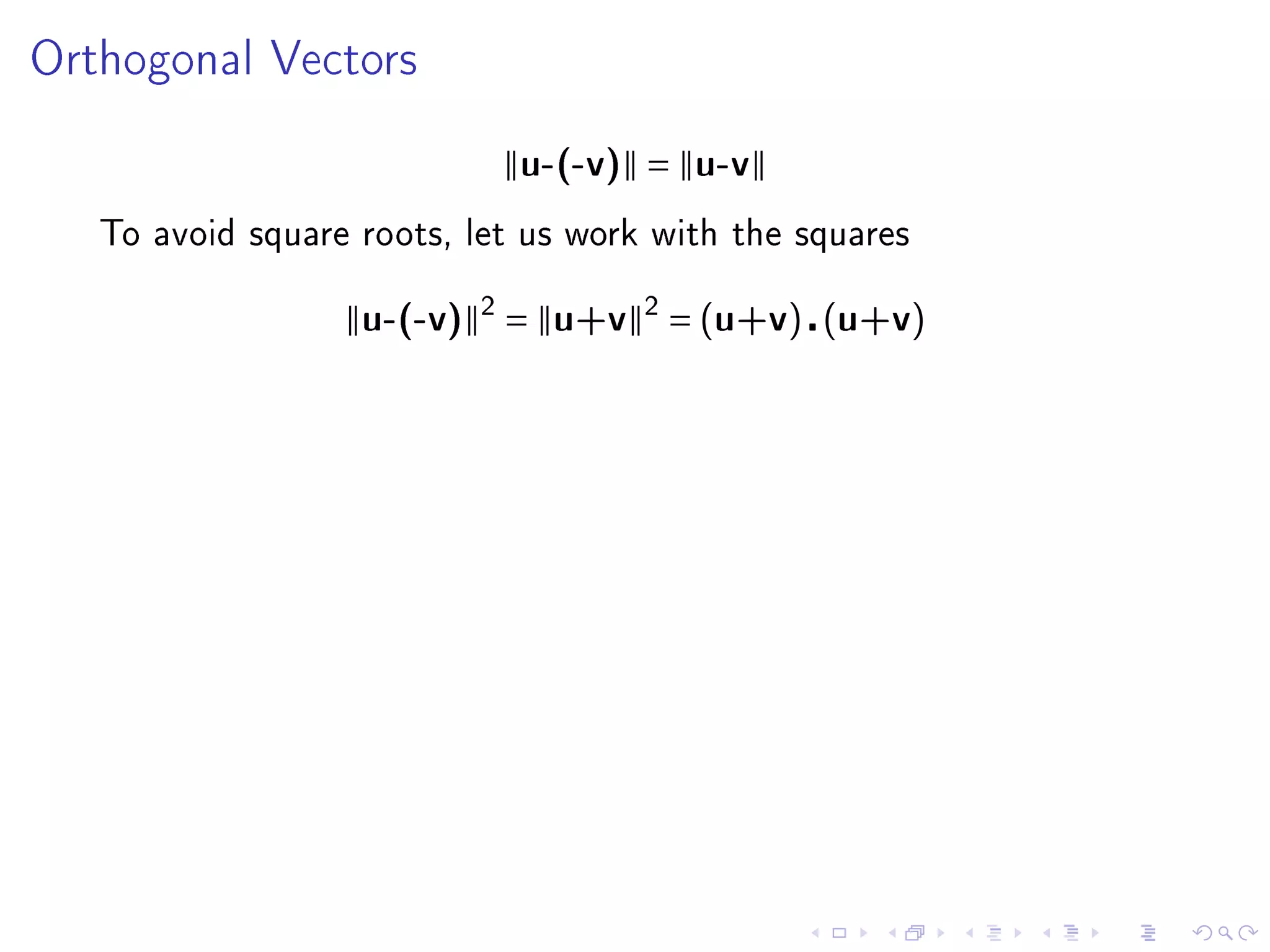

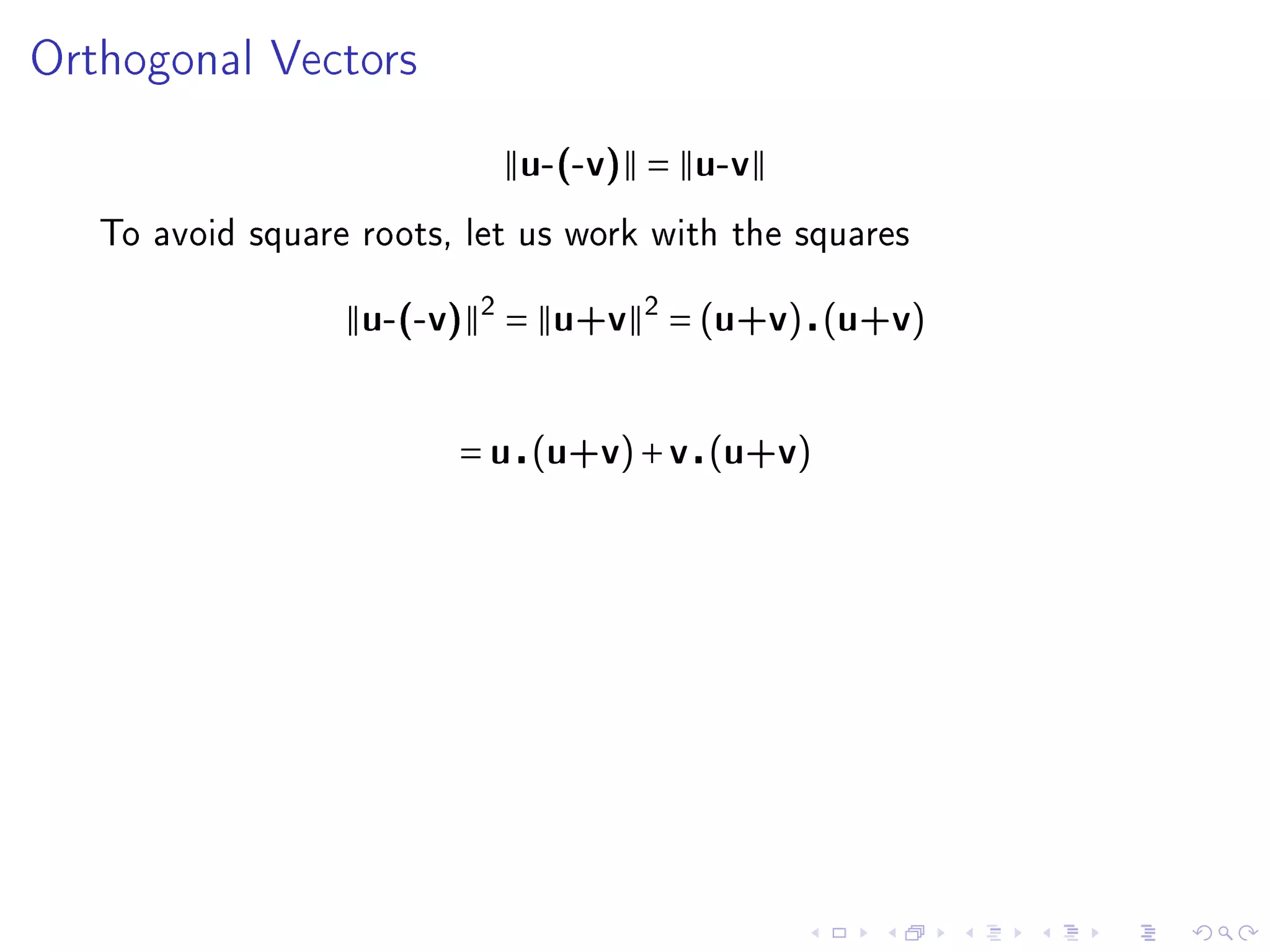

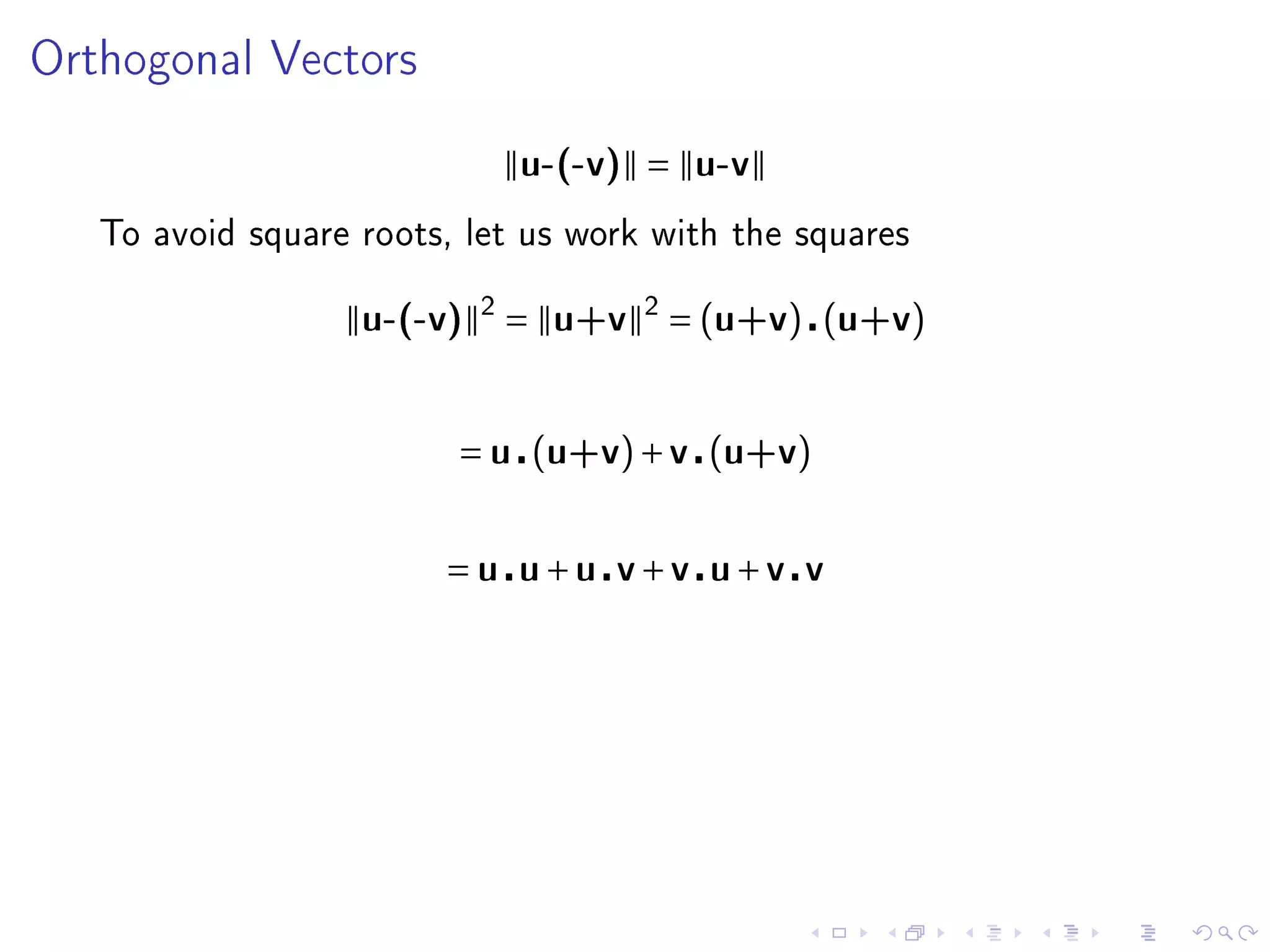

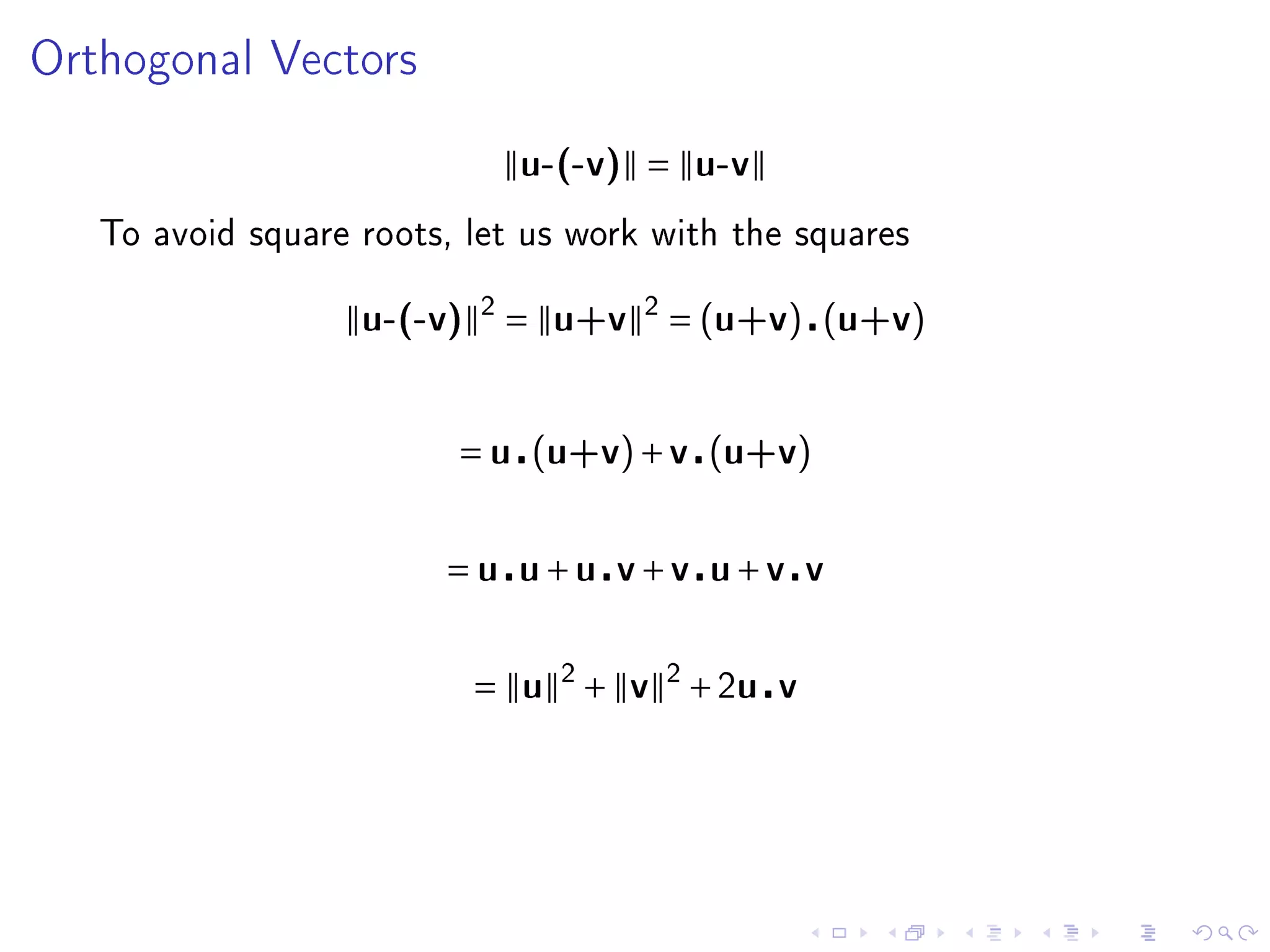

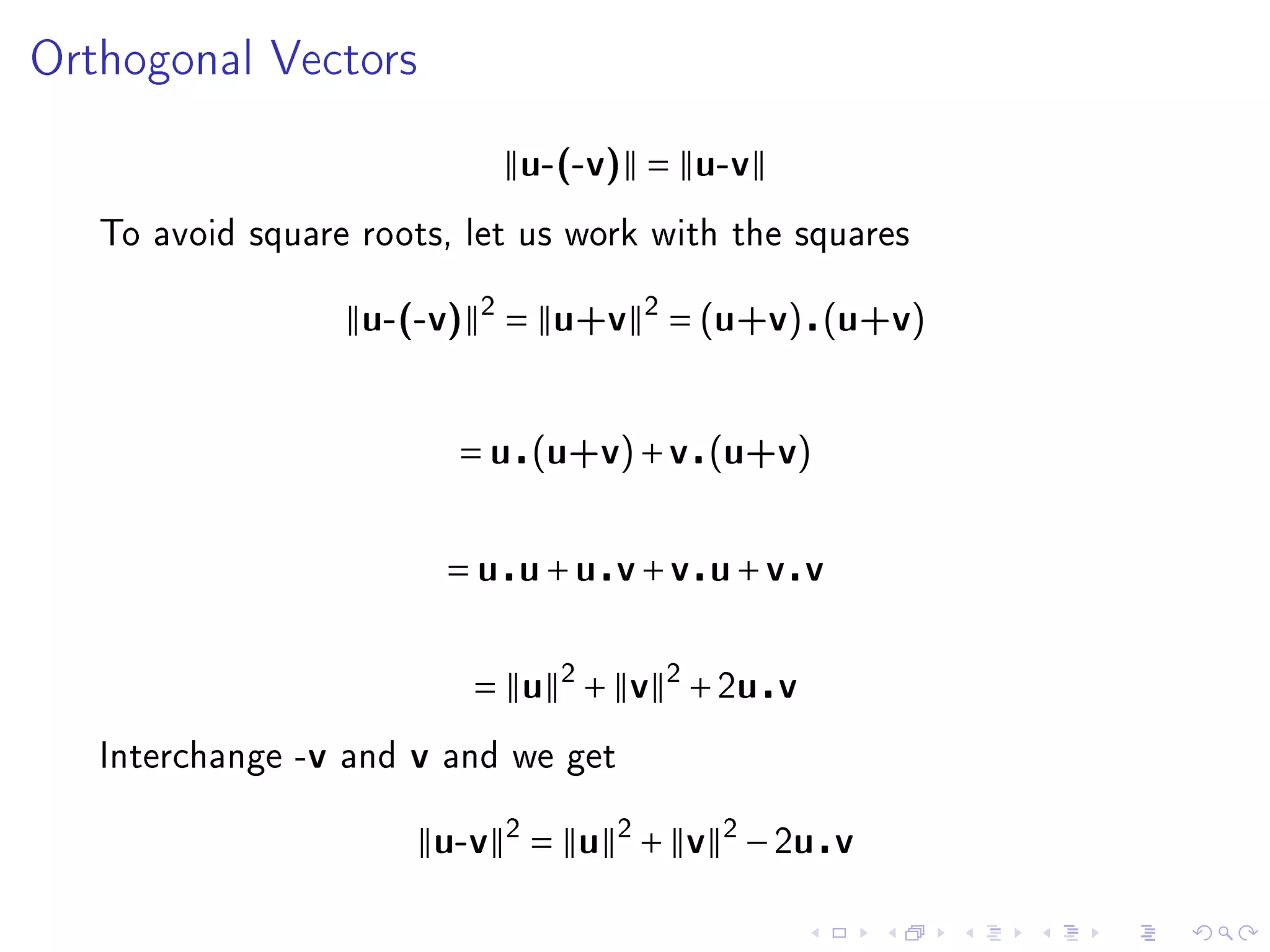

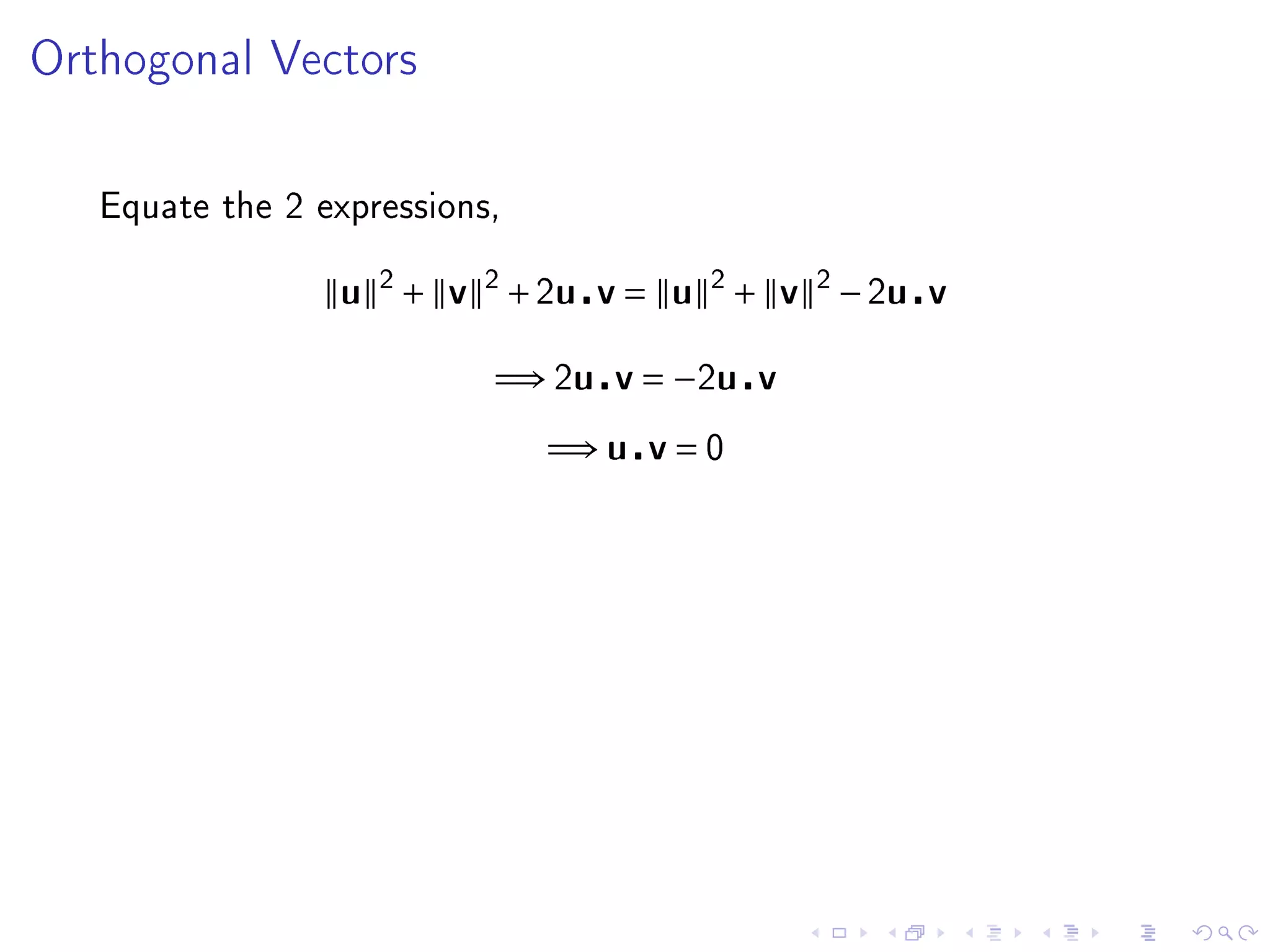

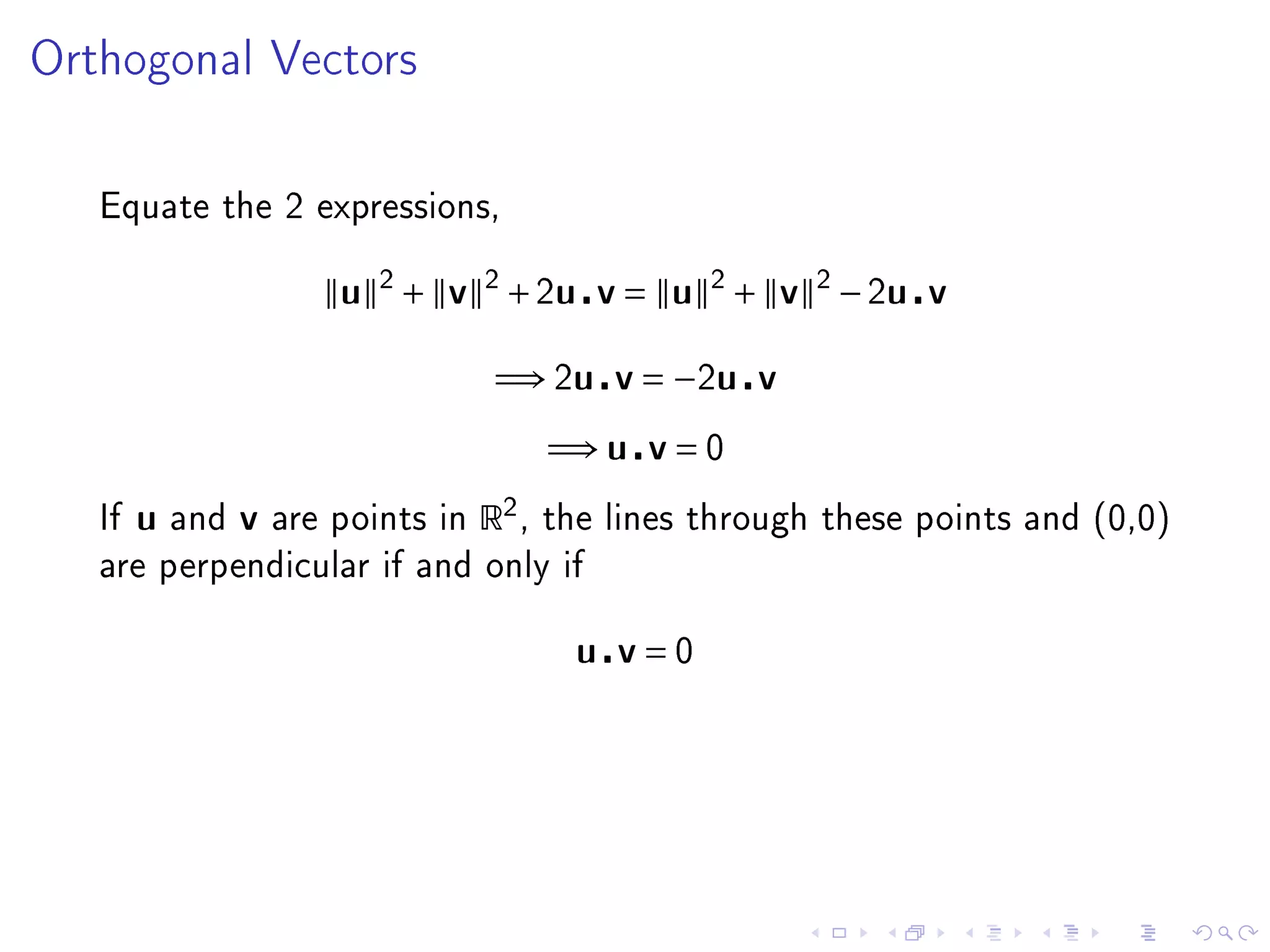

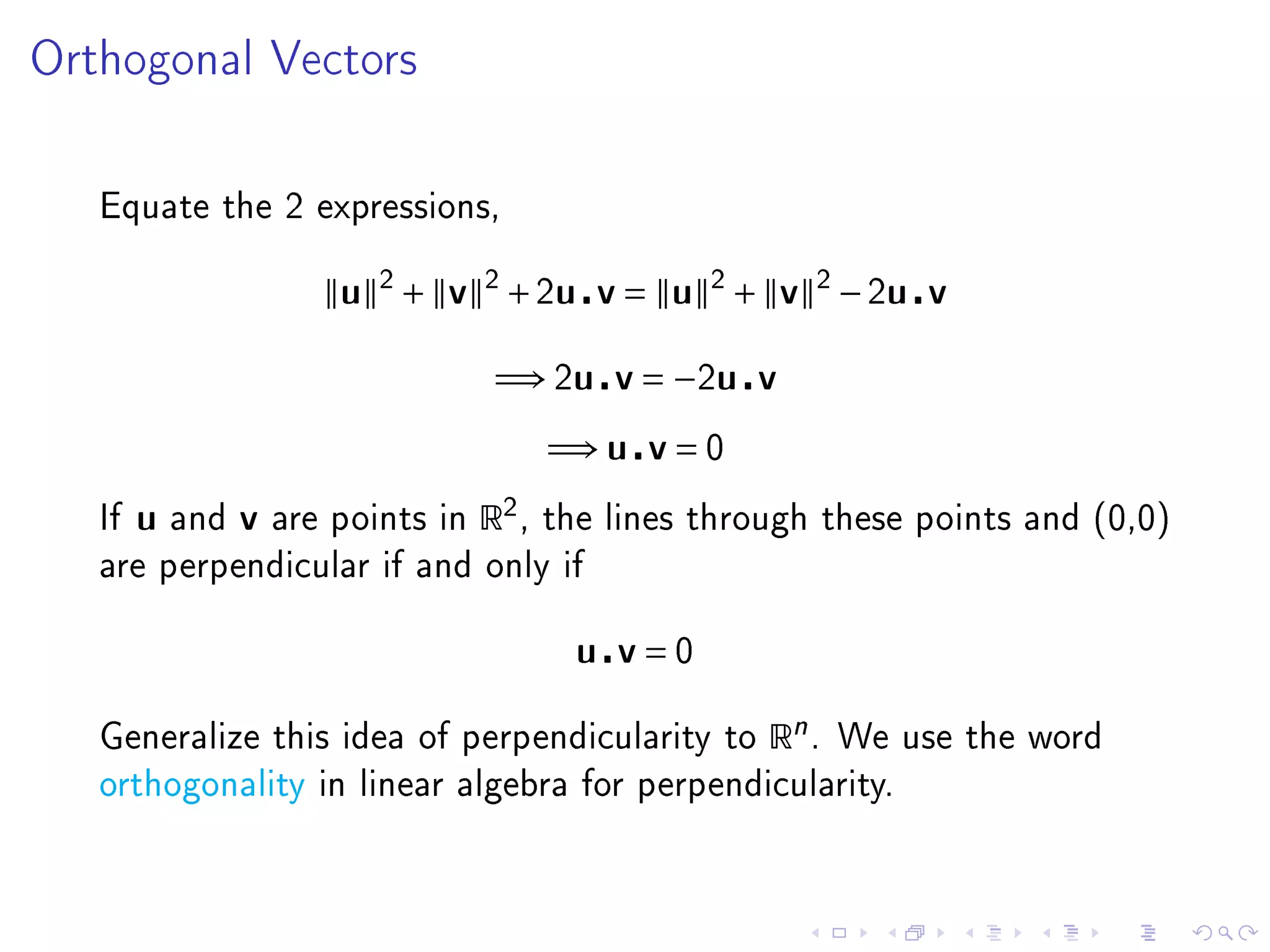

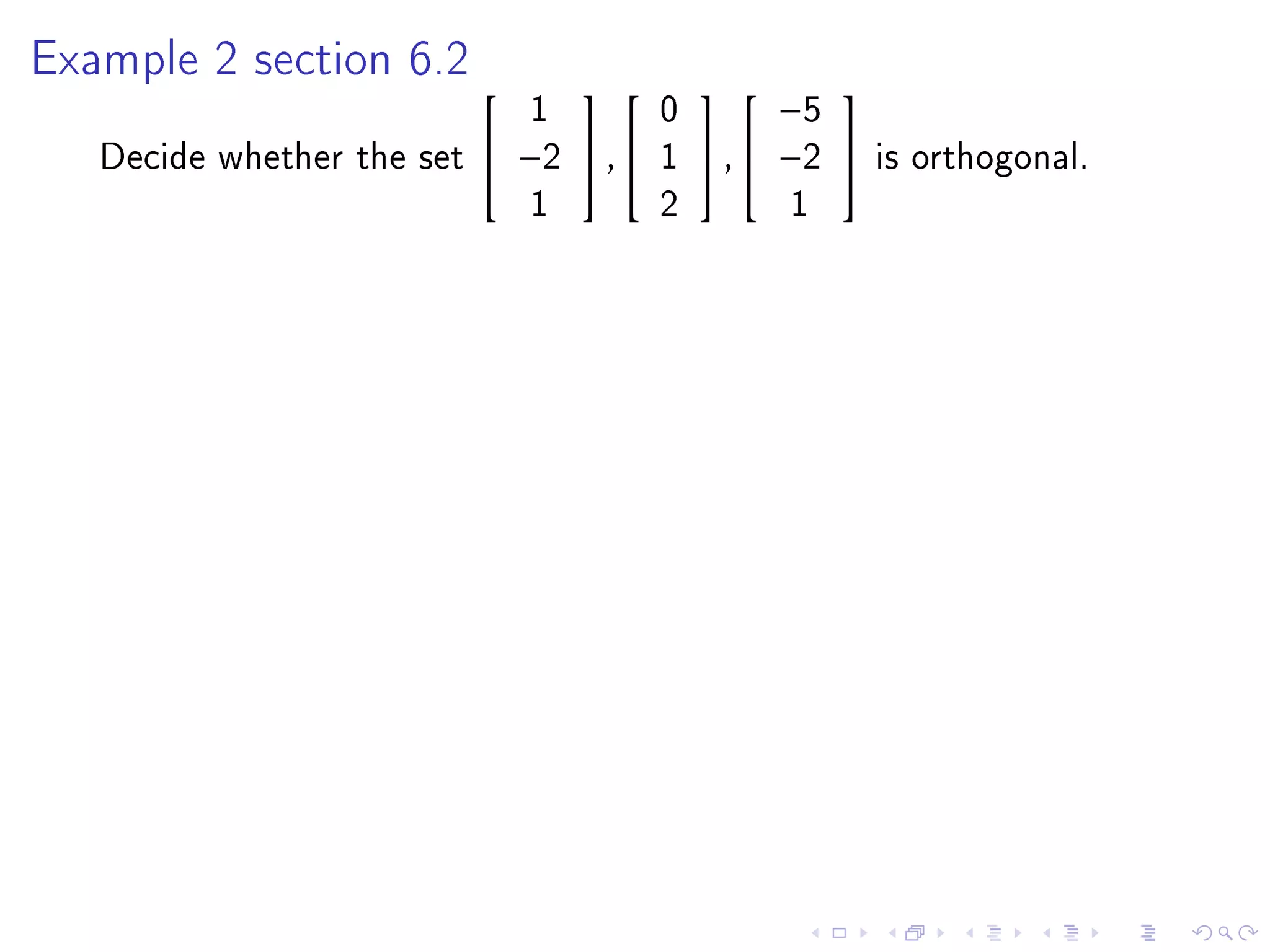

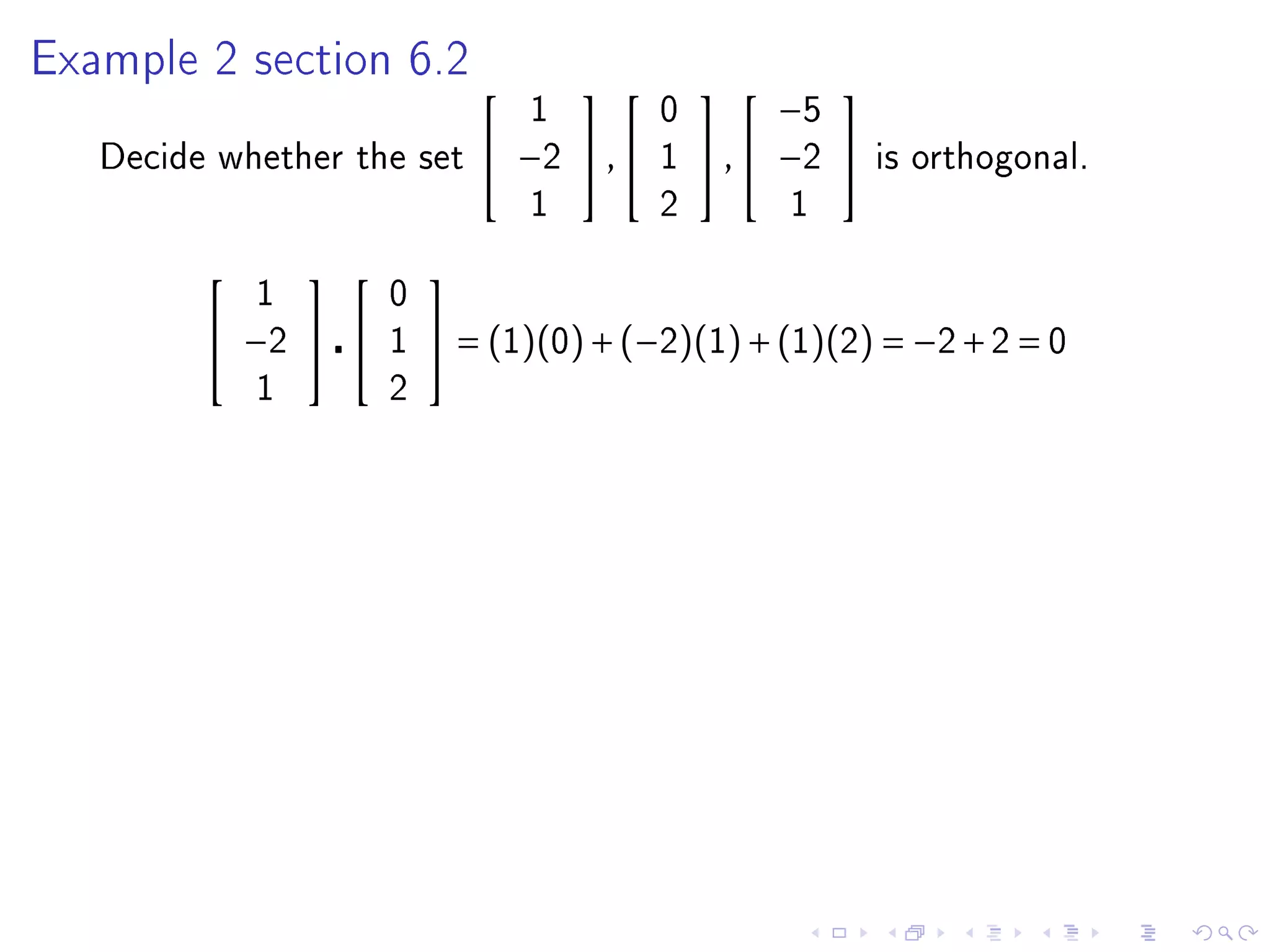

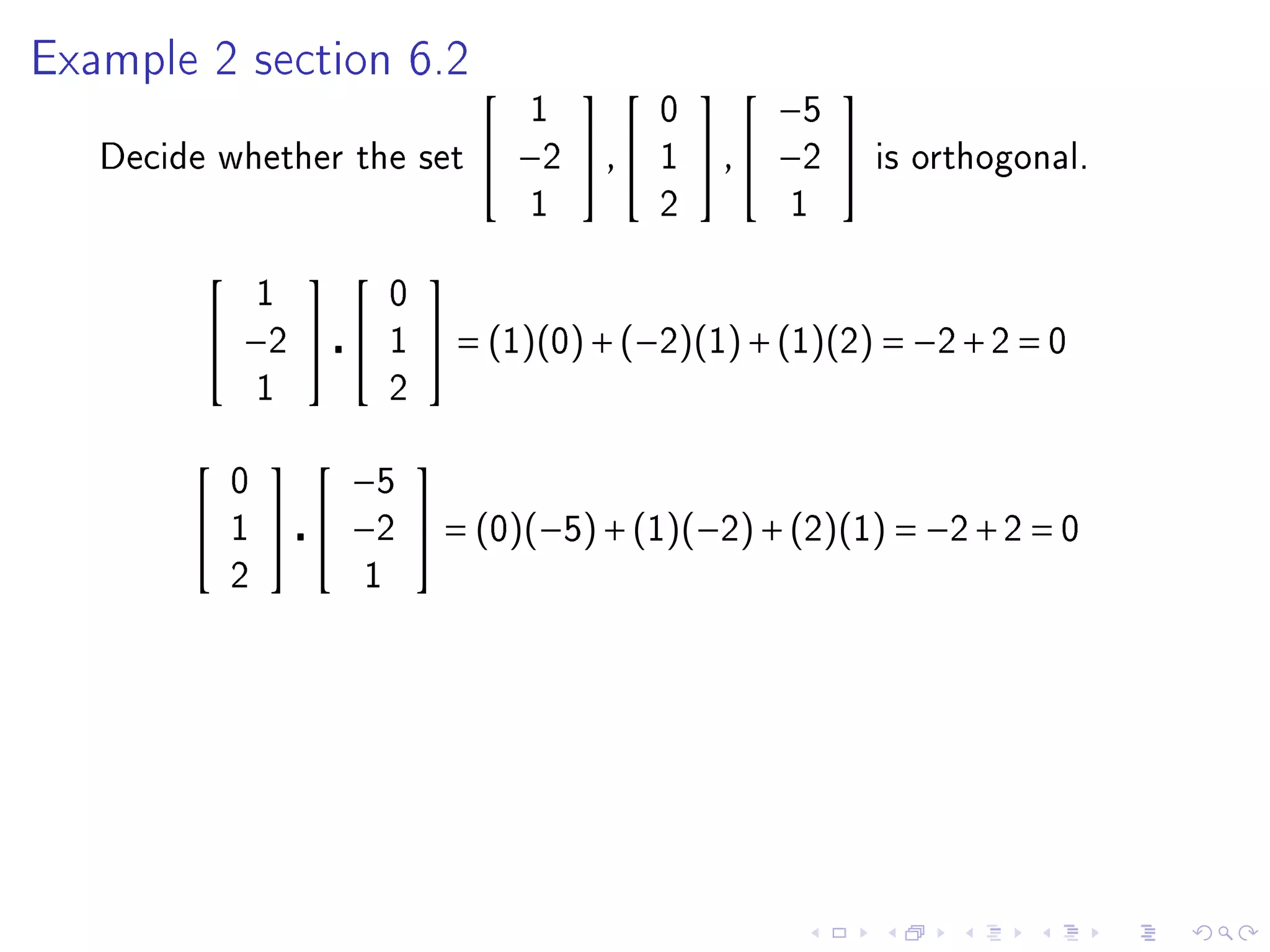

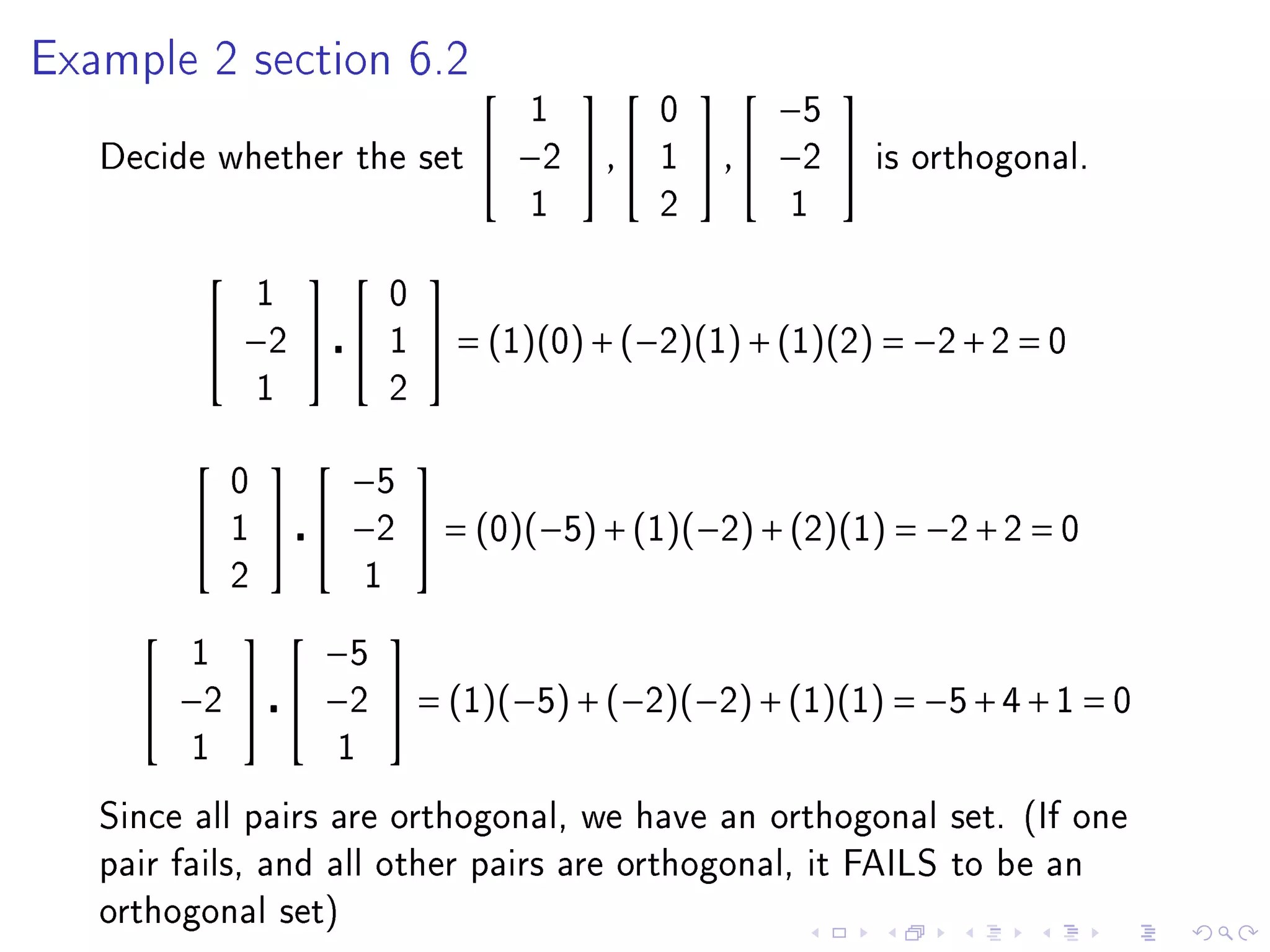

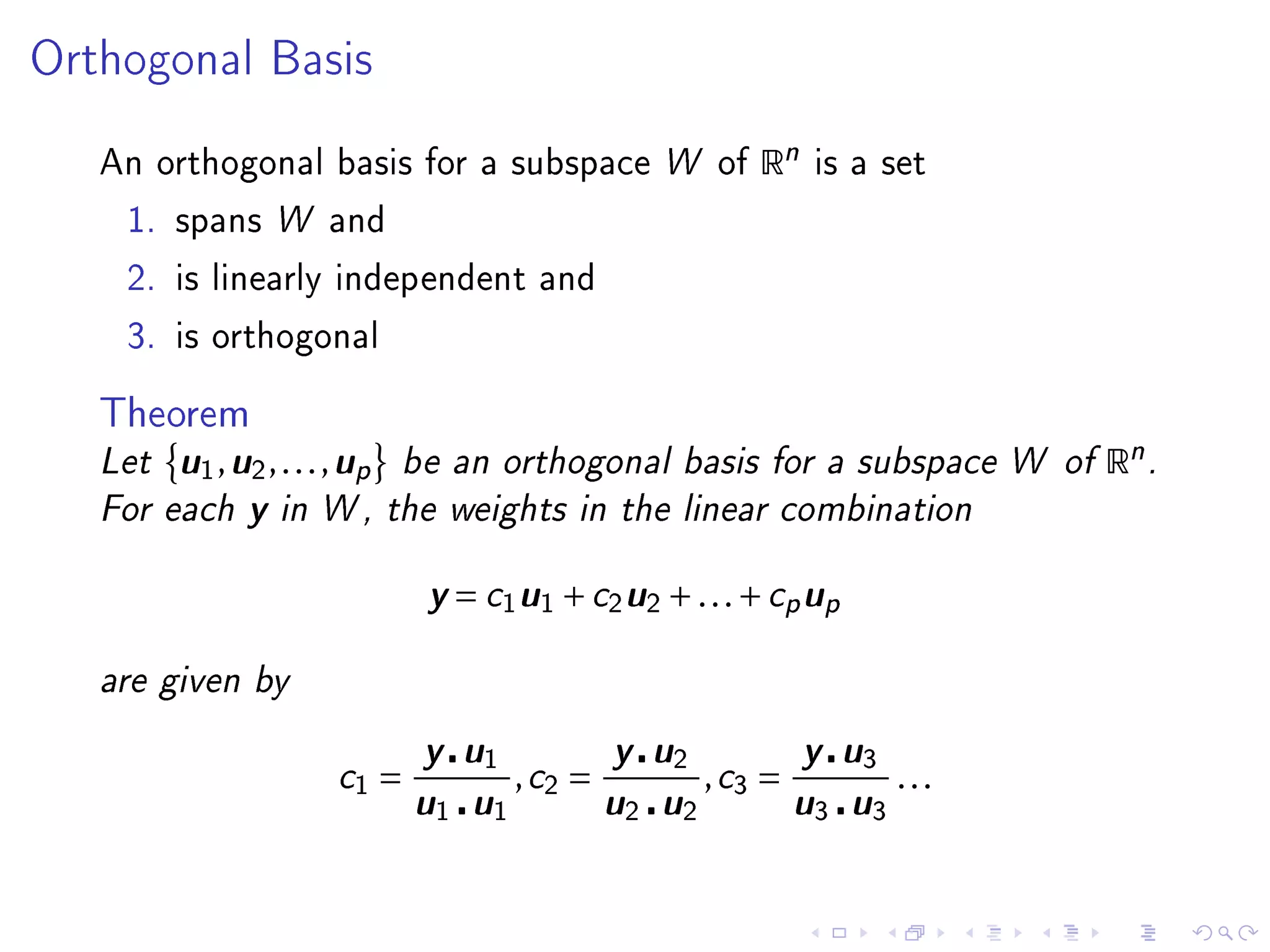

- Chapter 6 objectives include extending geometric concepts like length, distance, and perpendicularity to Rn. These concepts are useful for least squares fitting of experimental data to a system of equations.

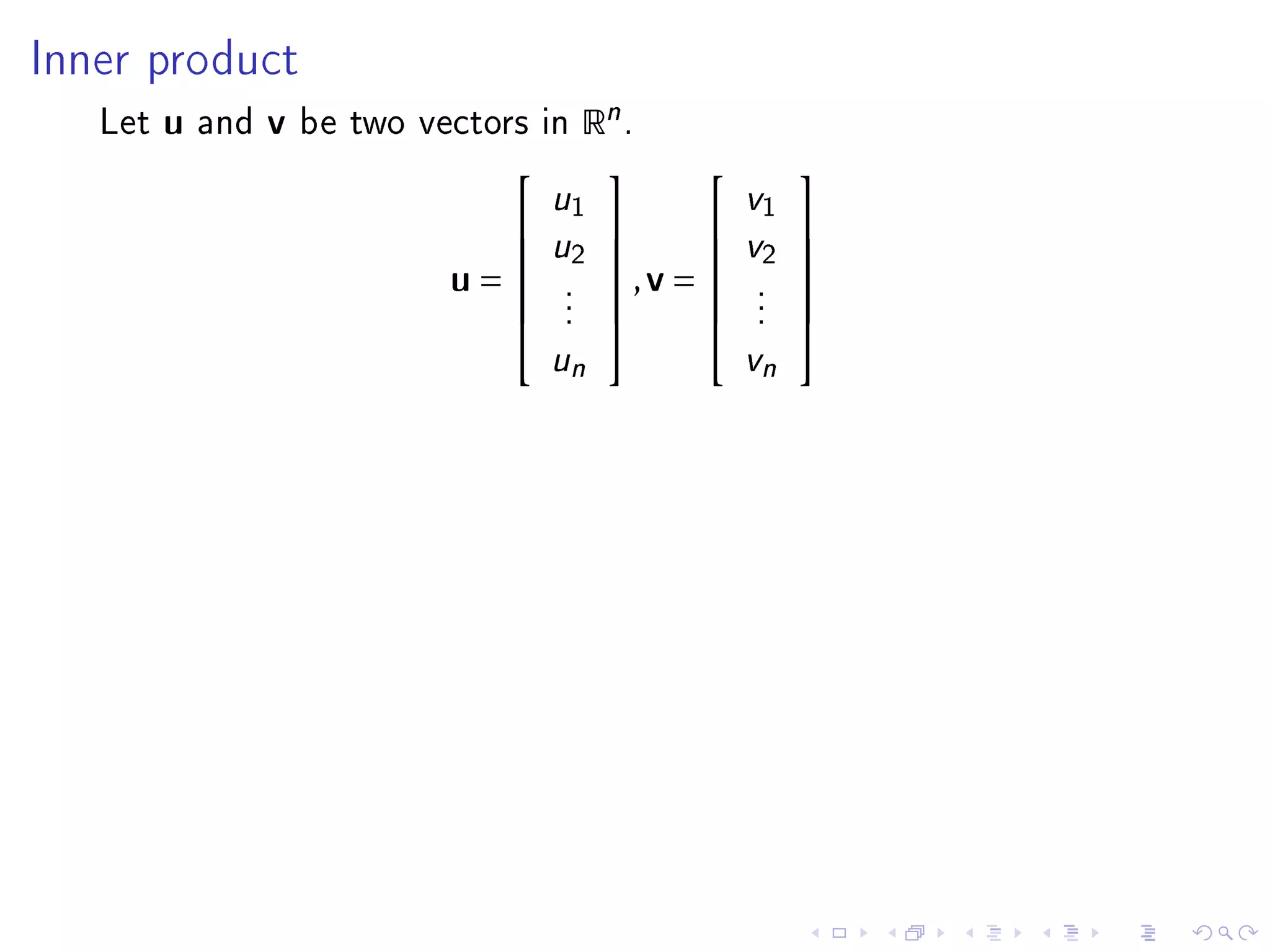

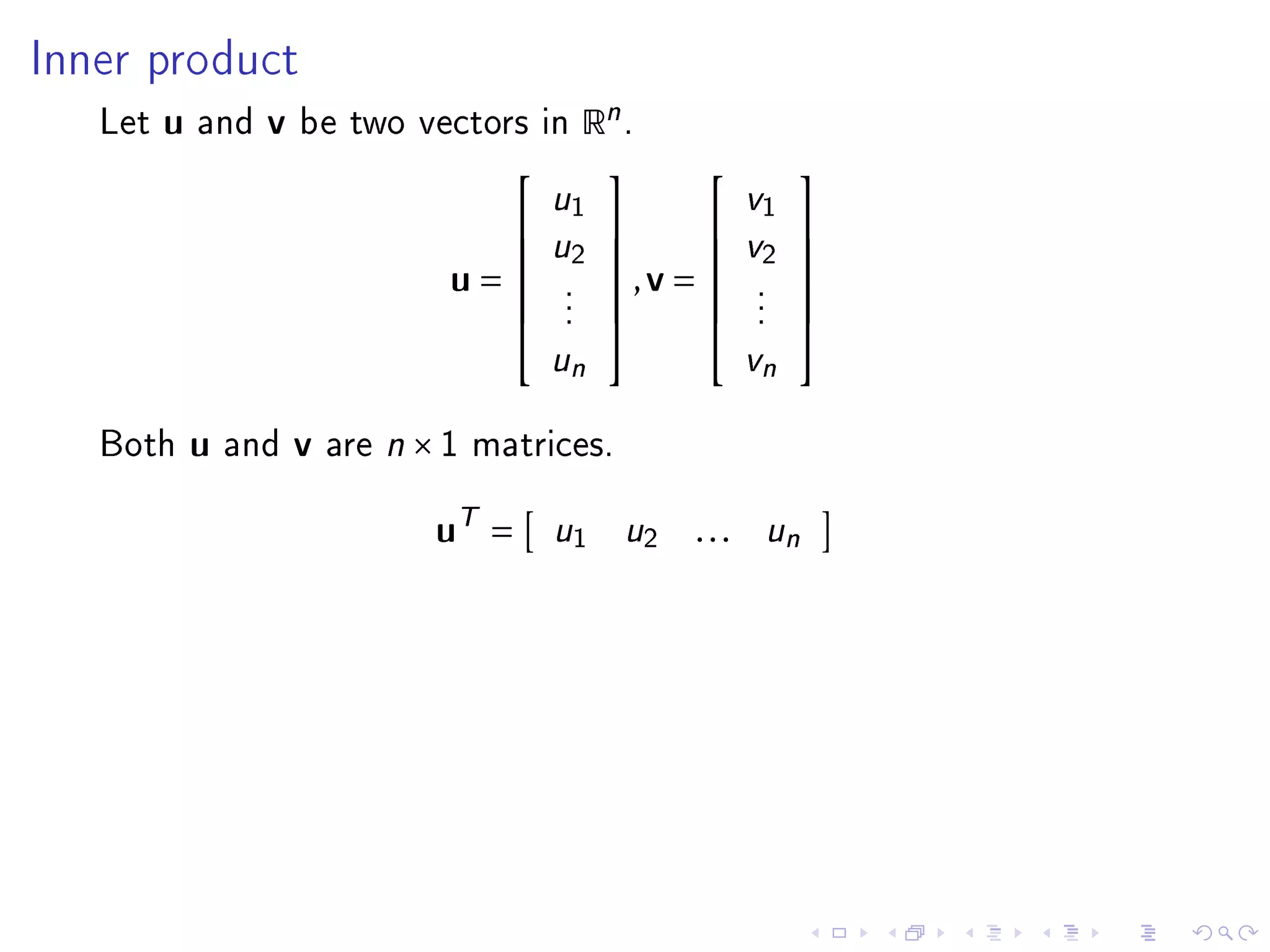

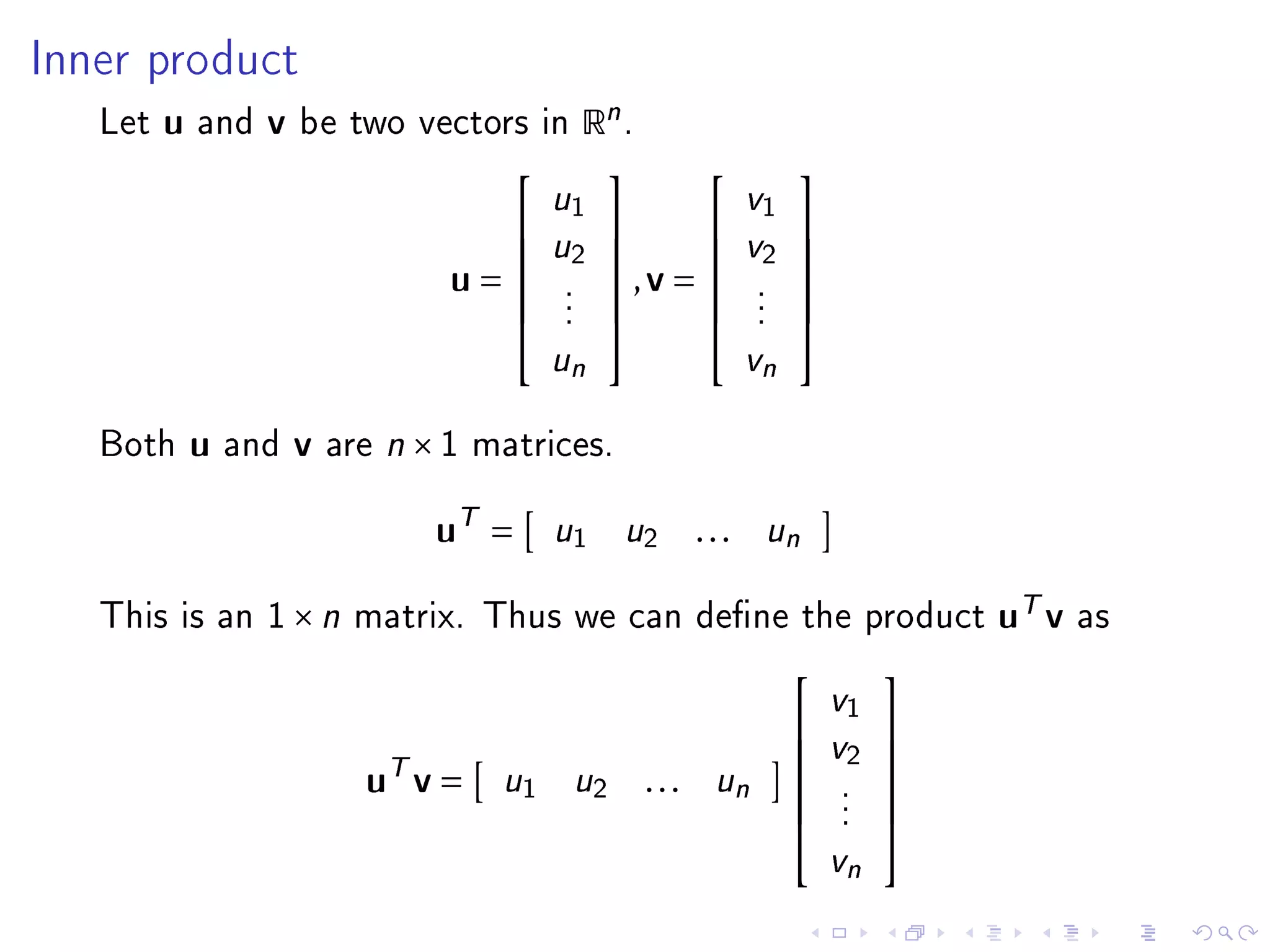

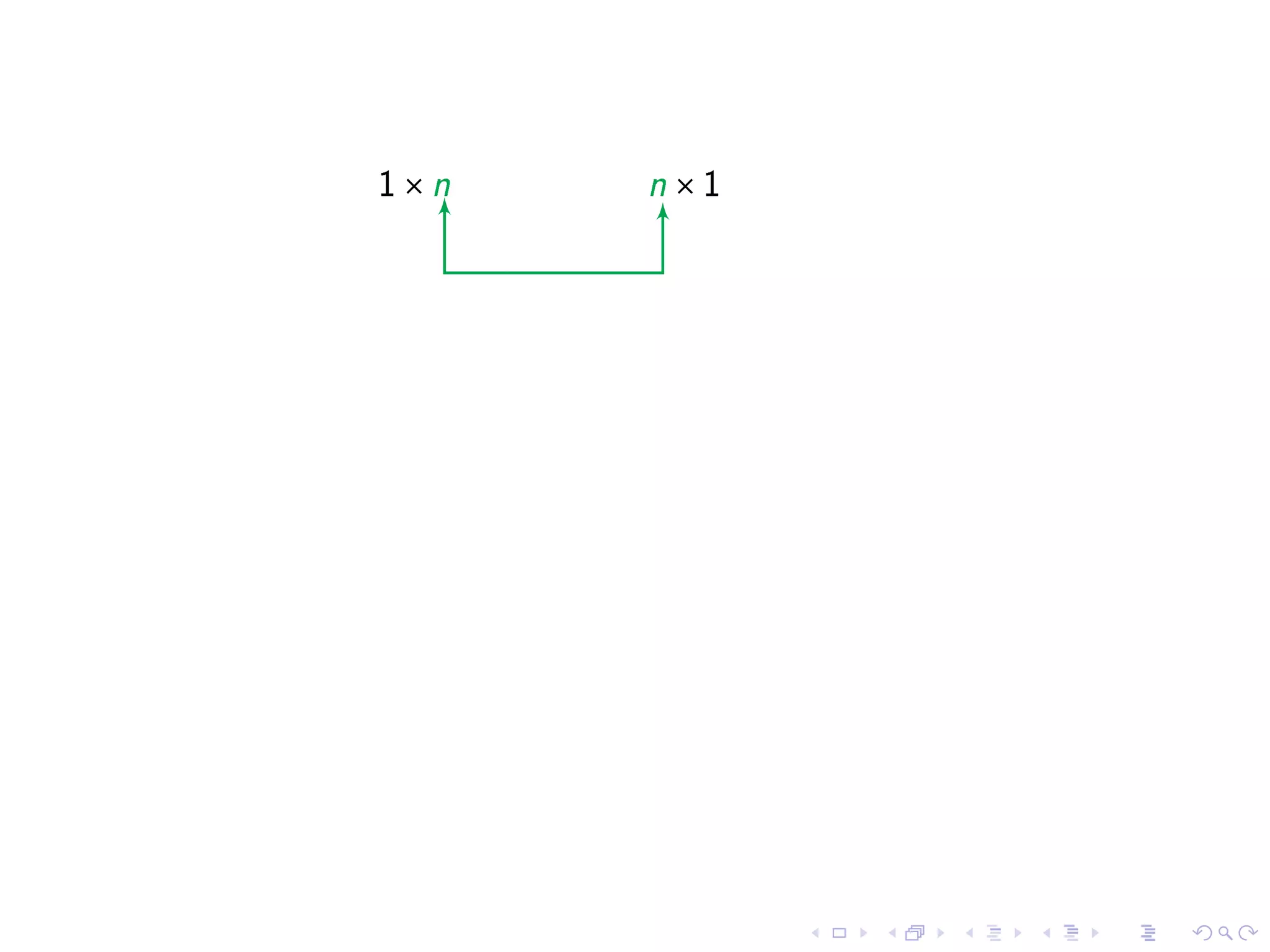

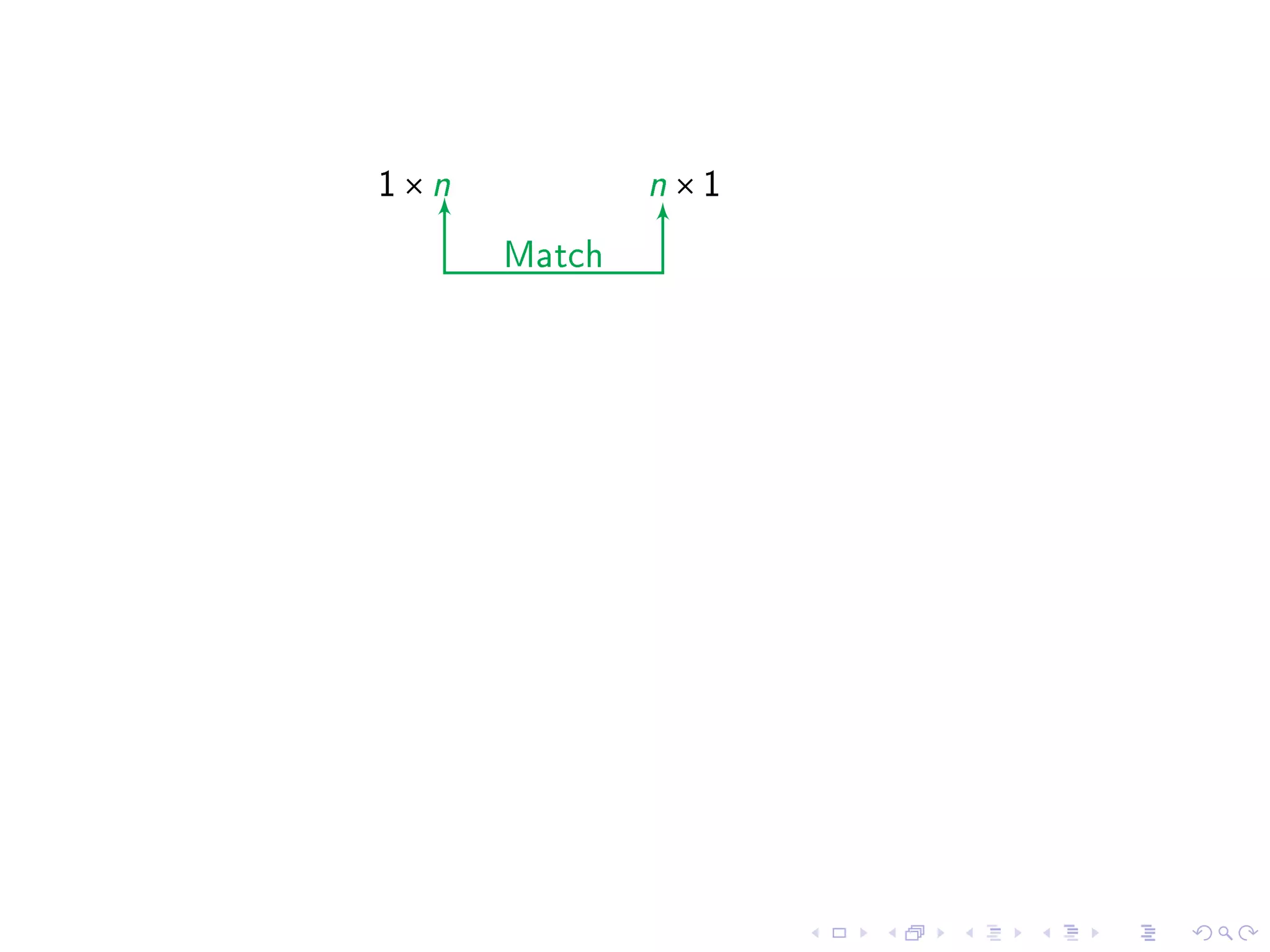

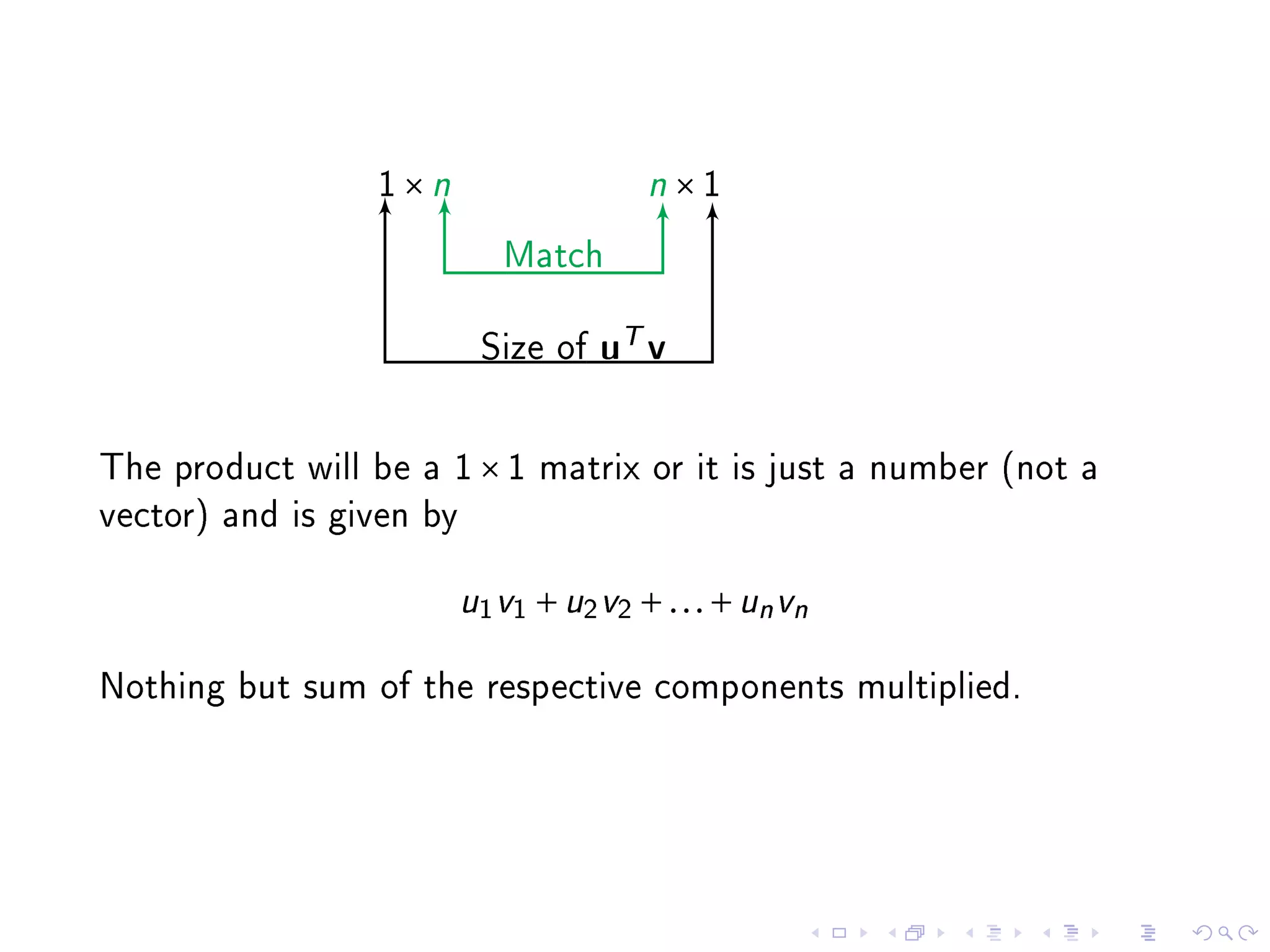

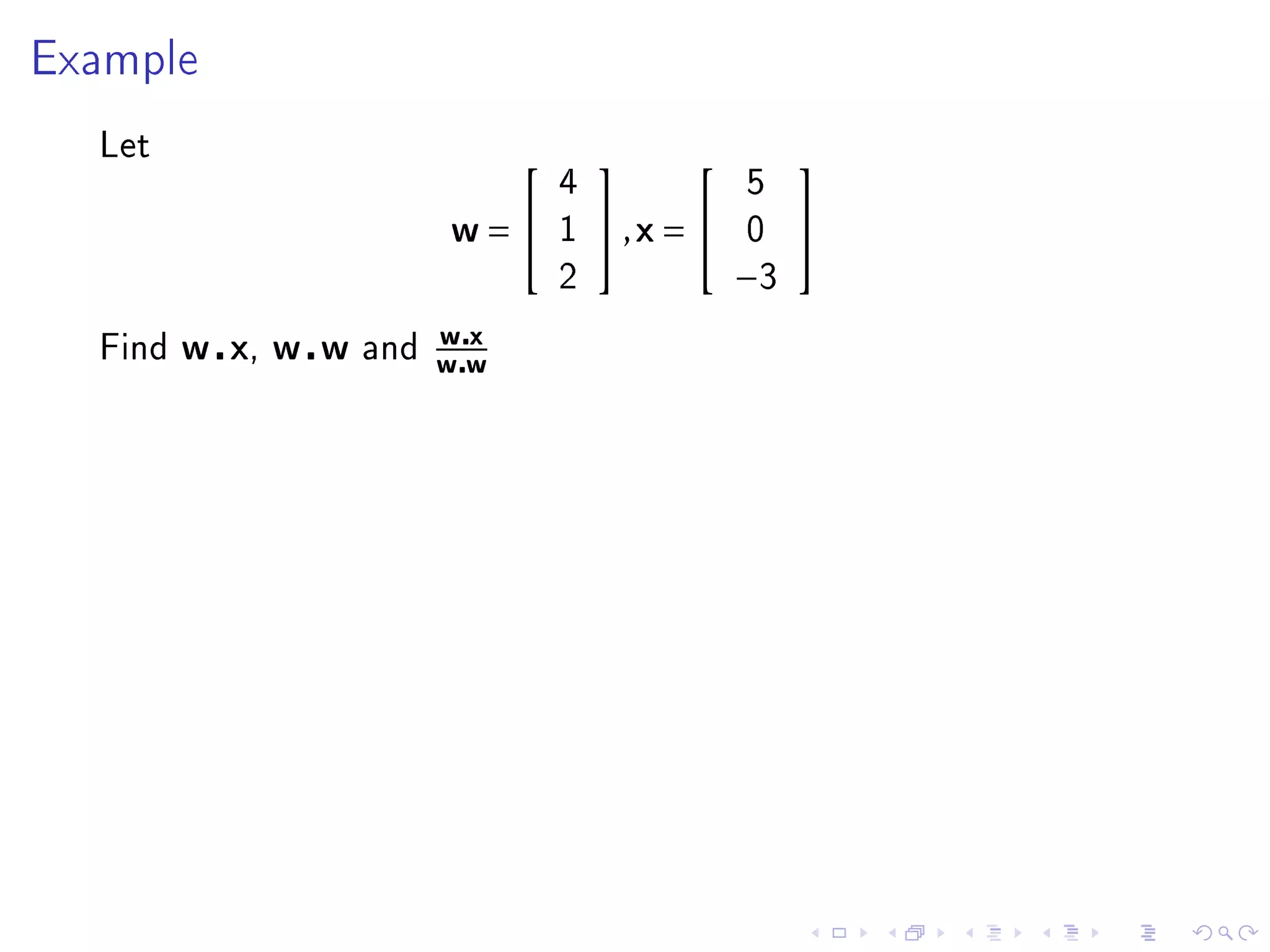

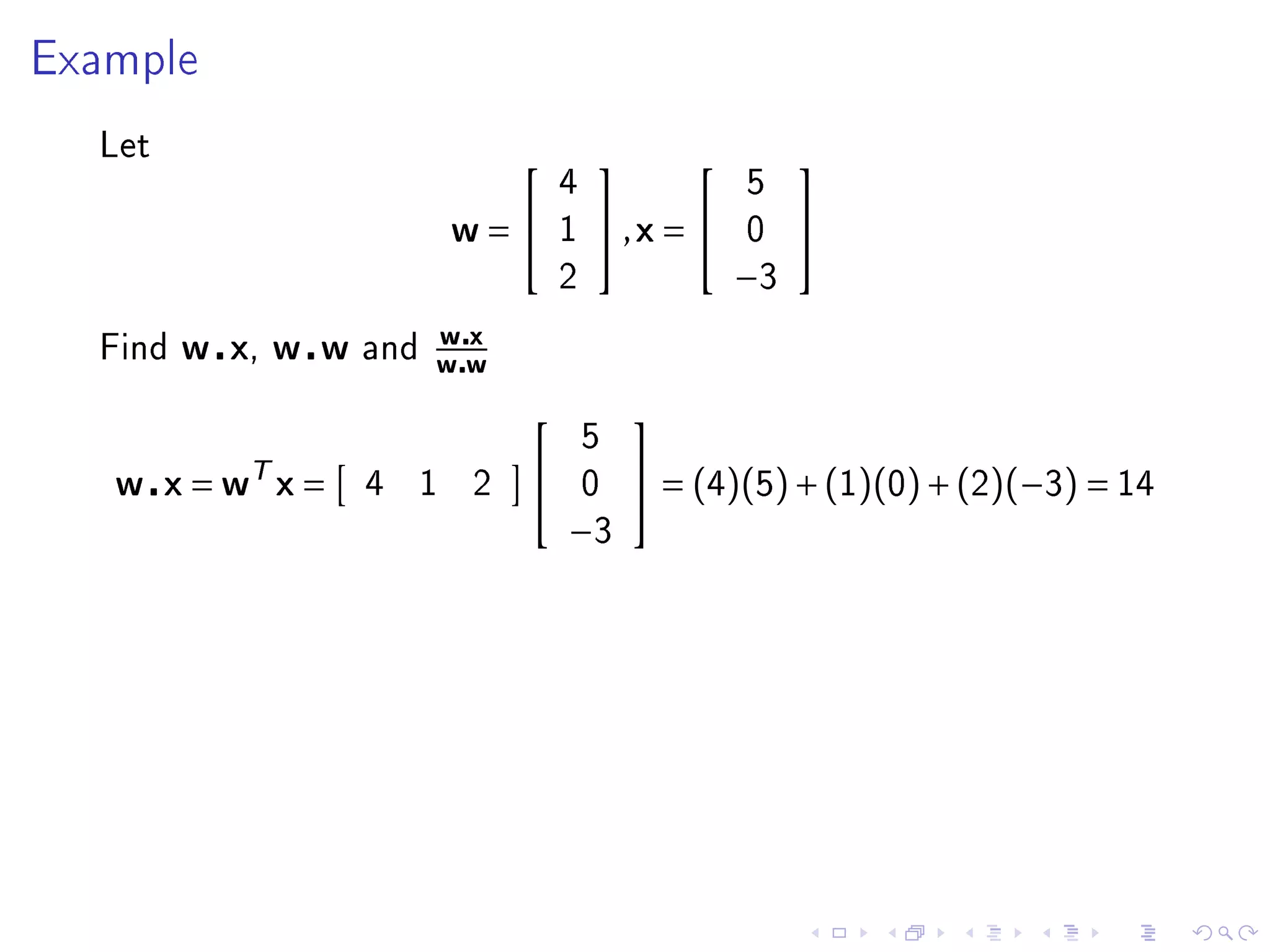

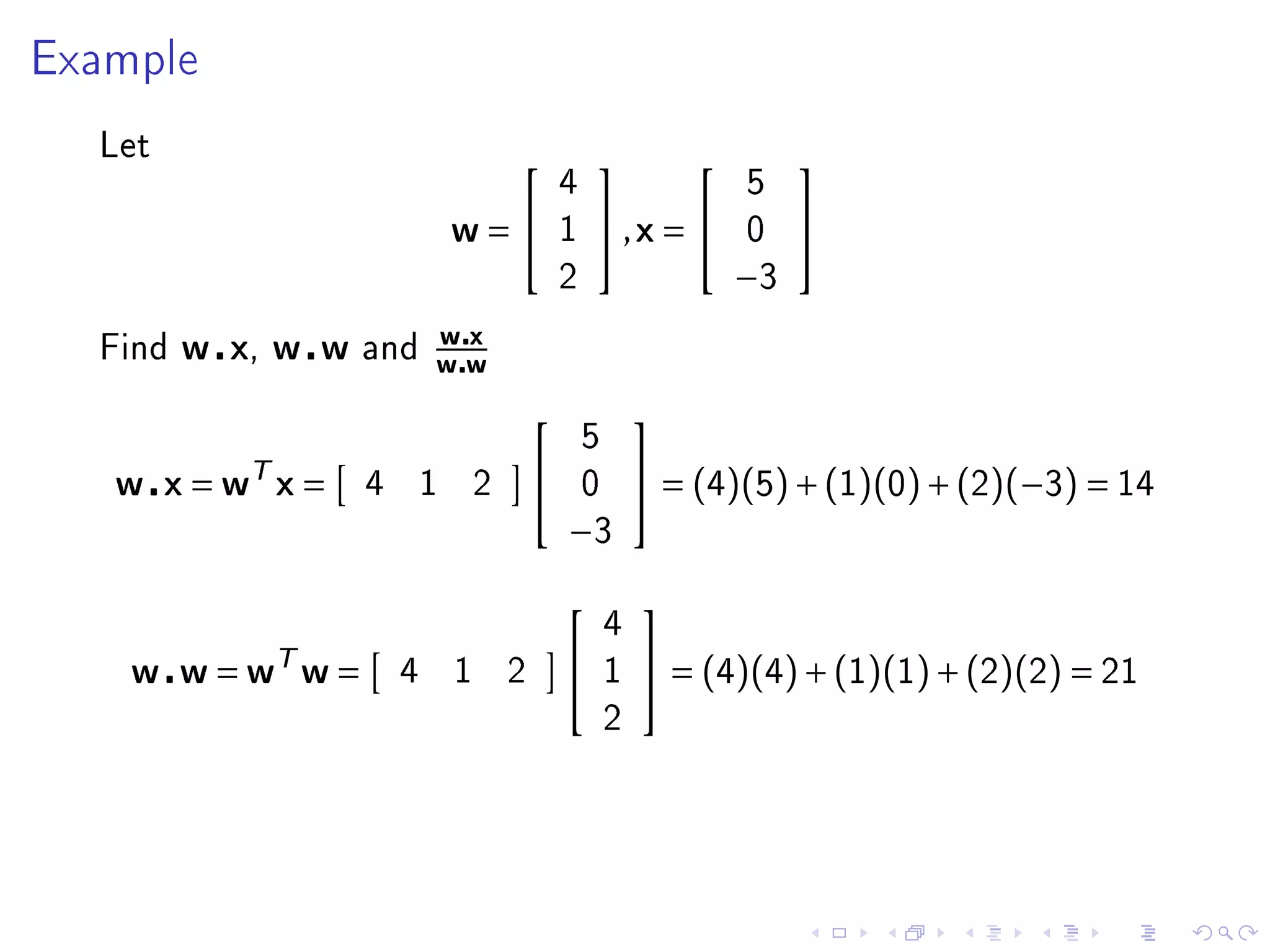

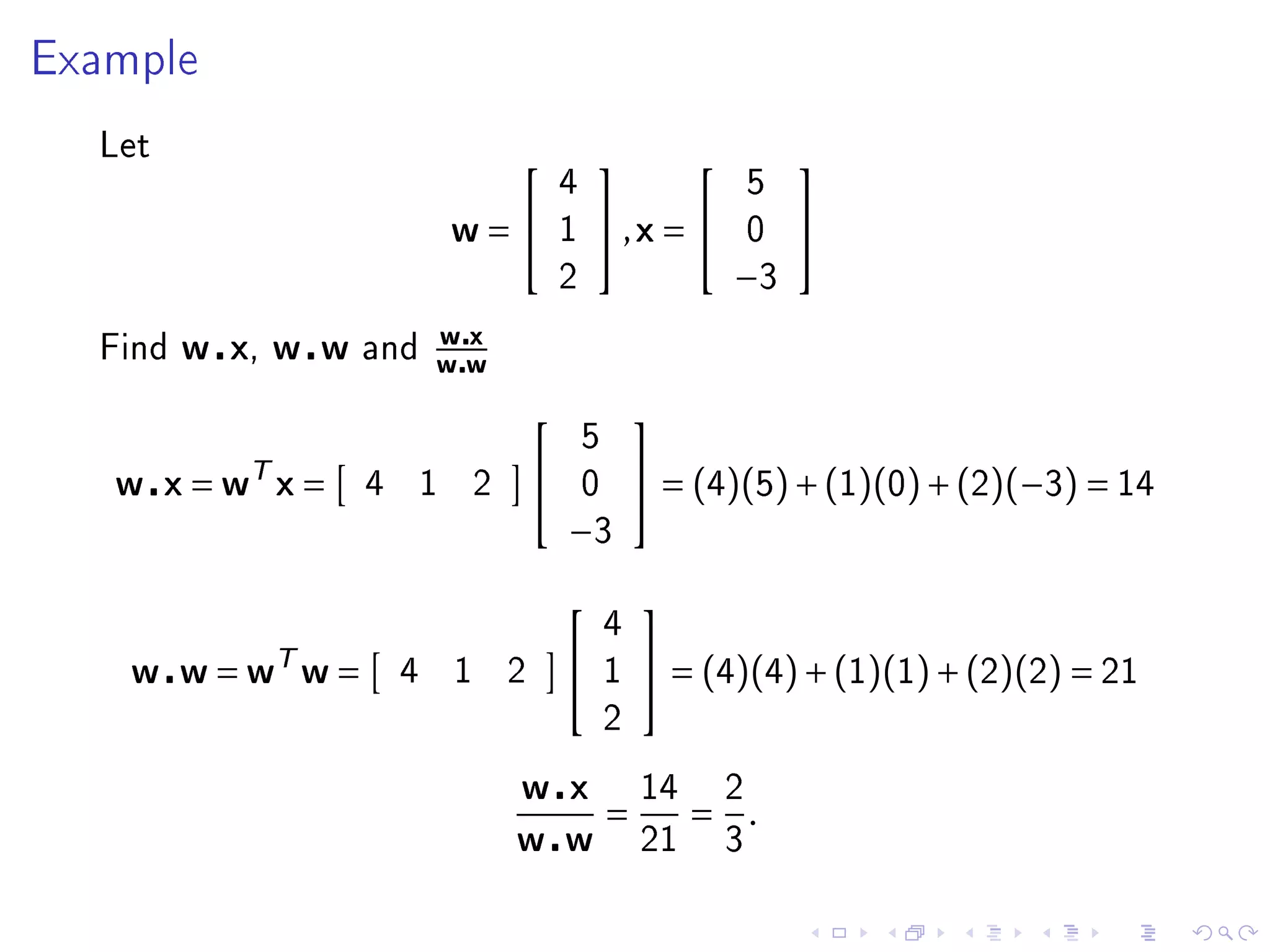

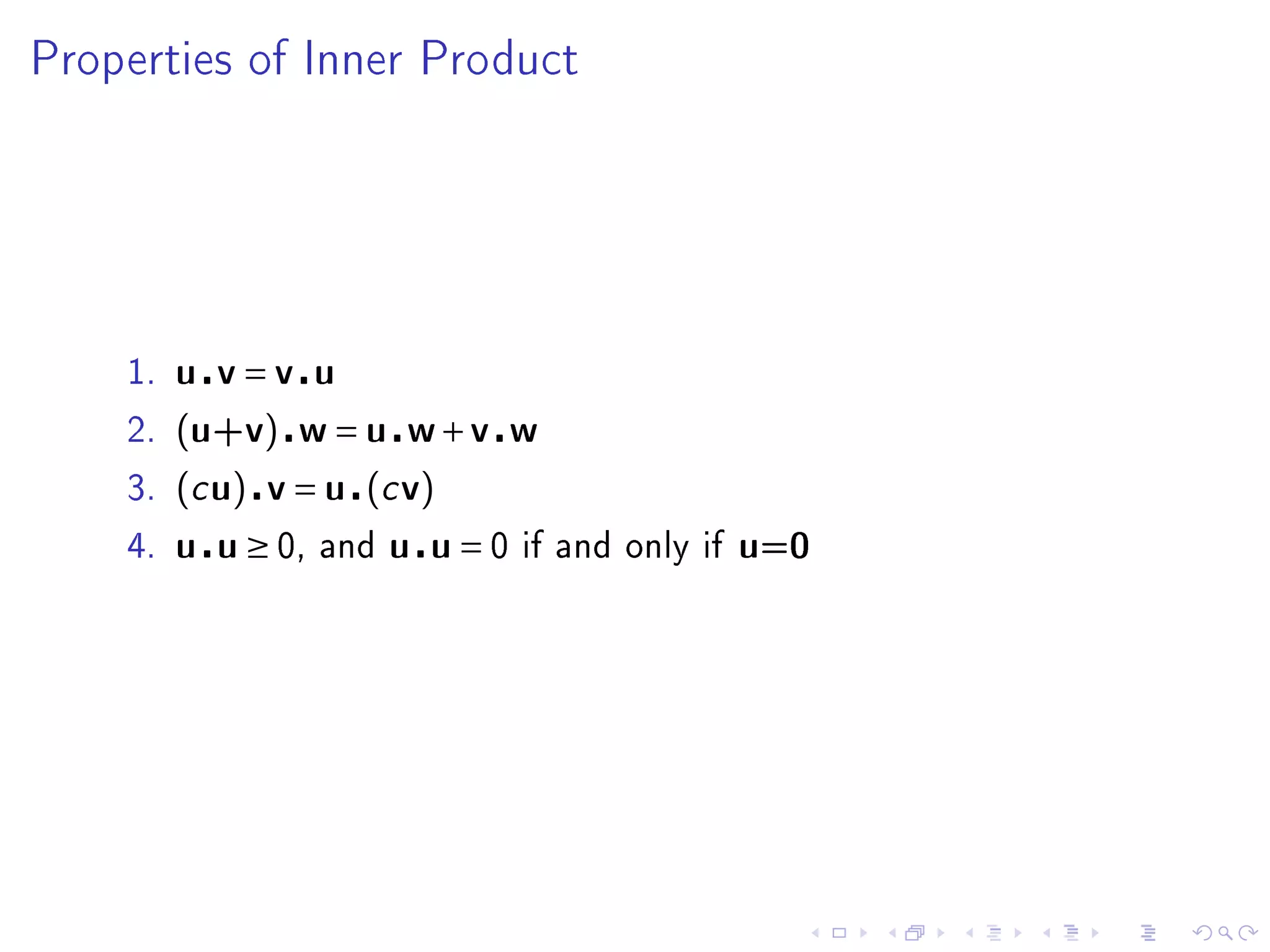

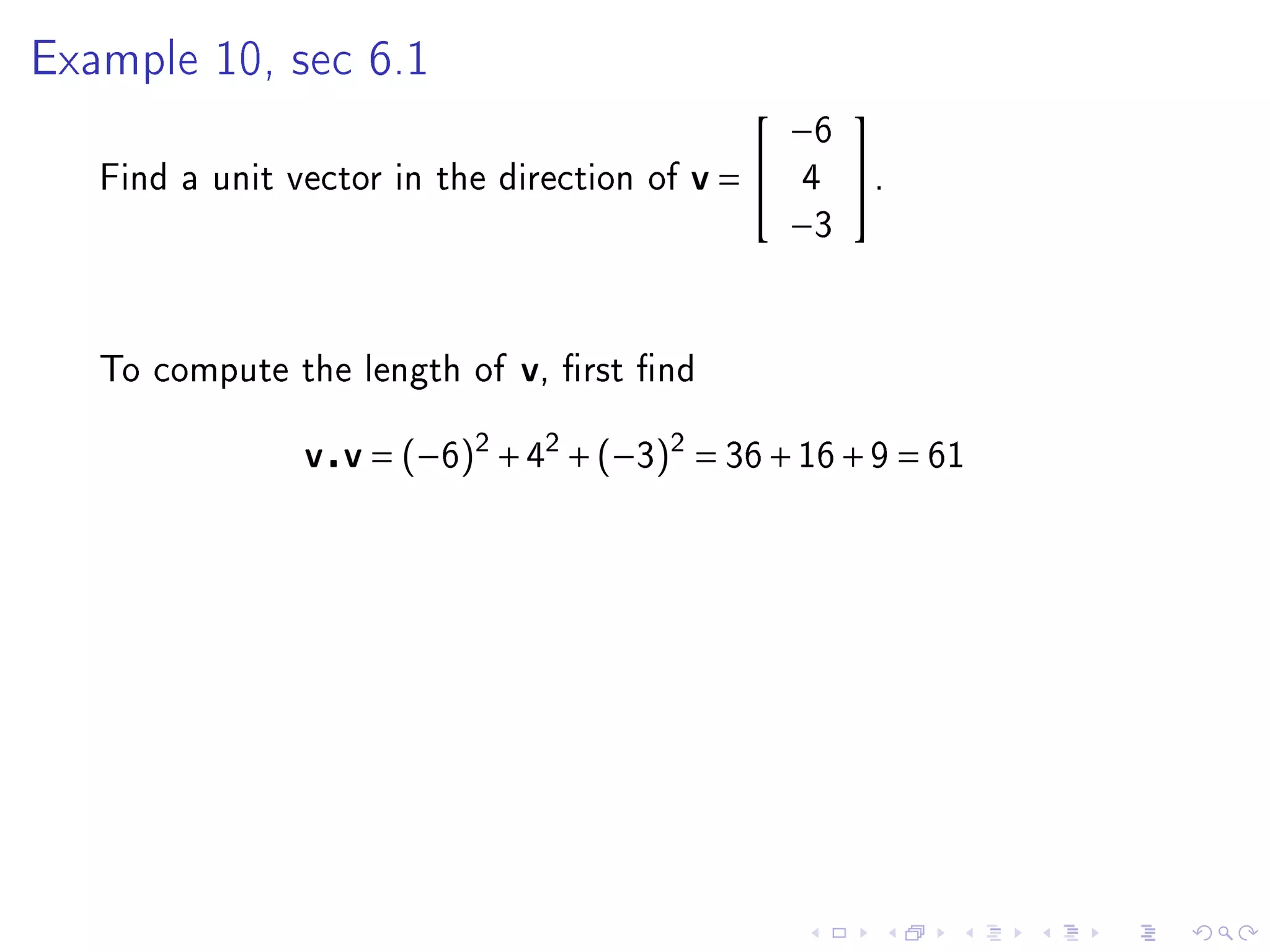

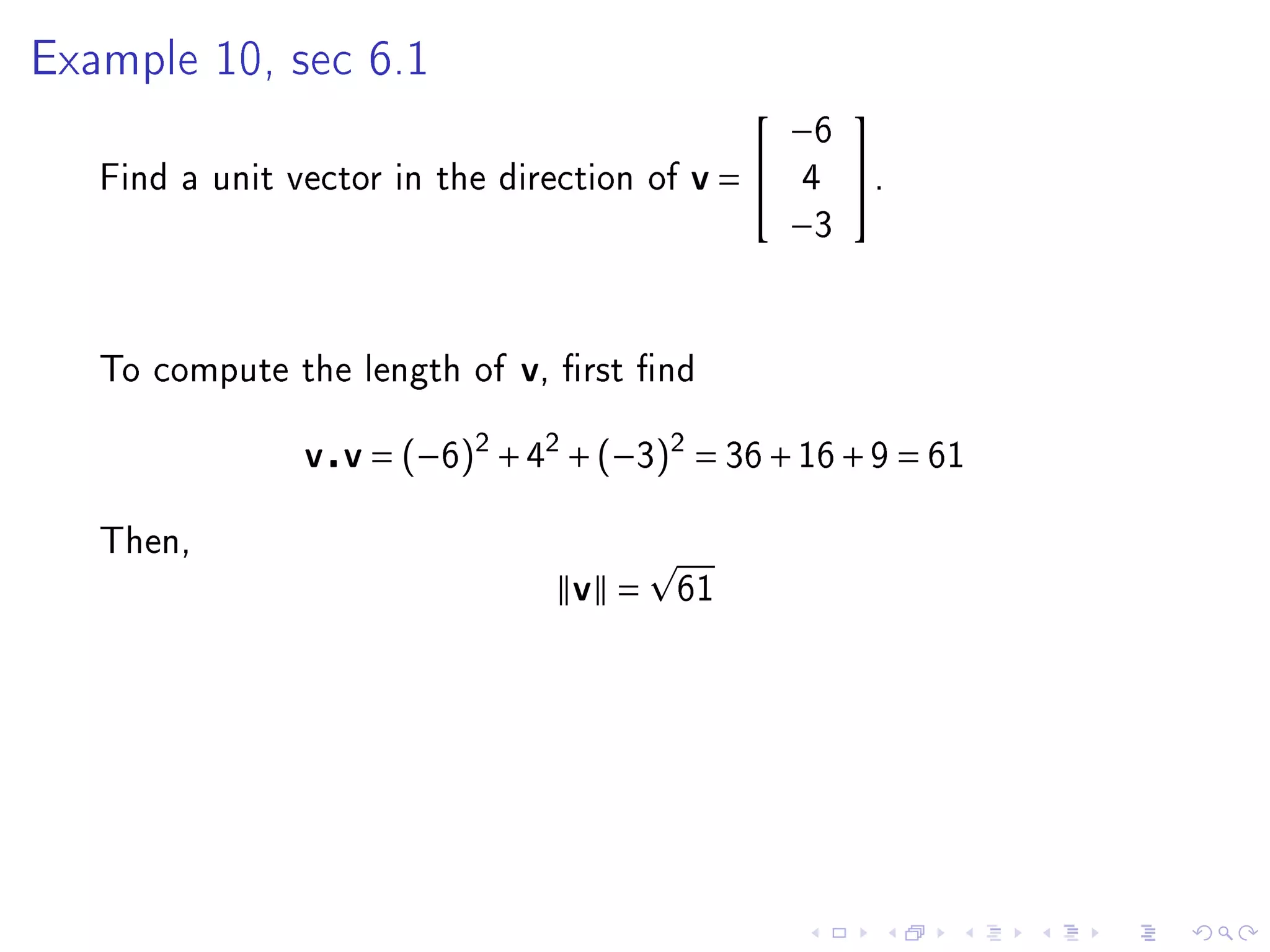

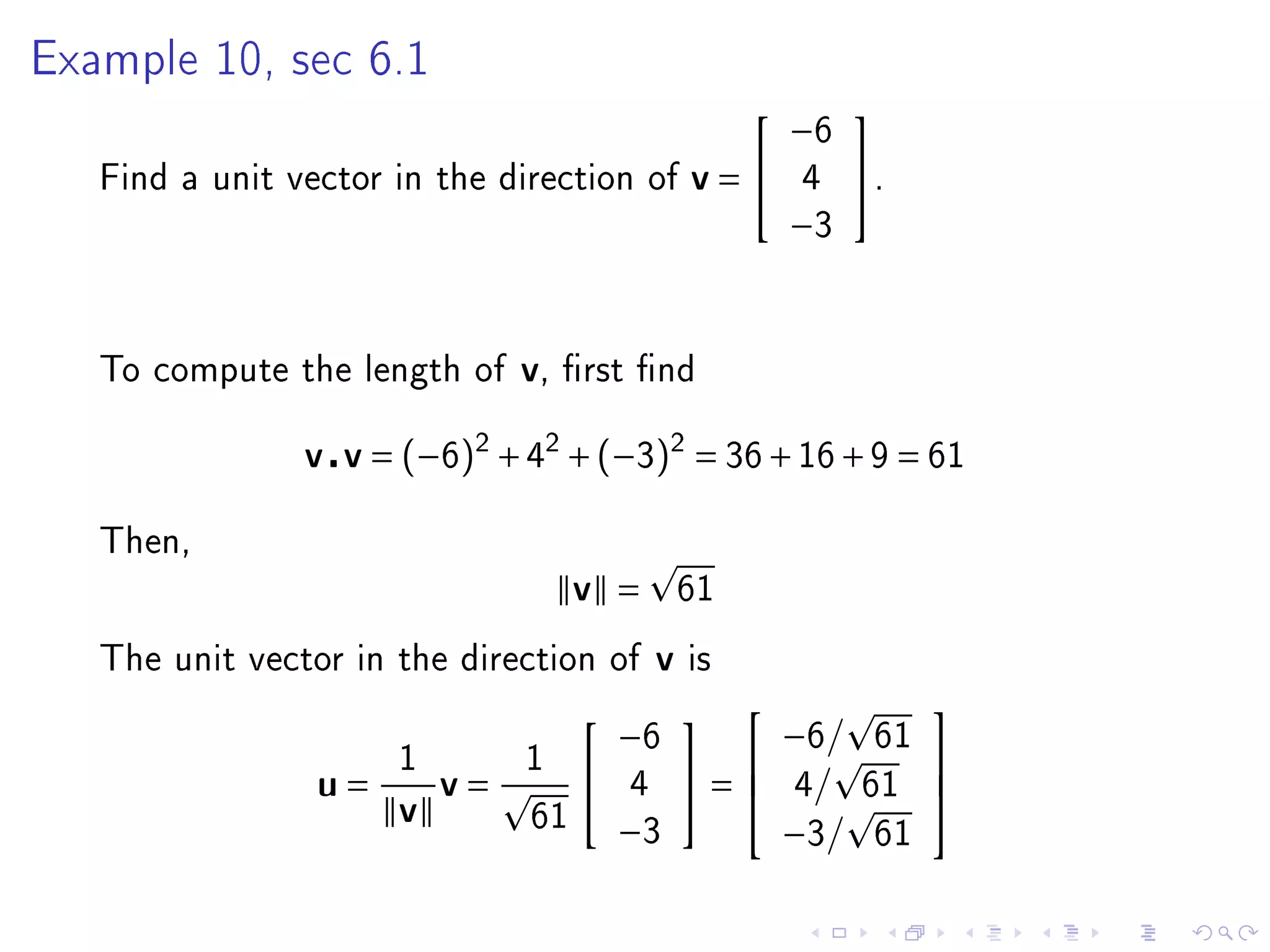

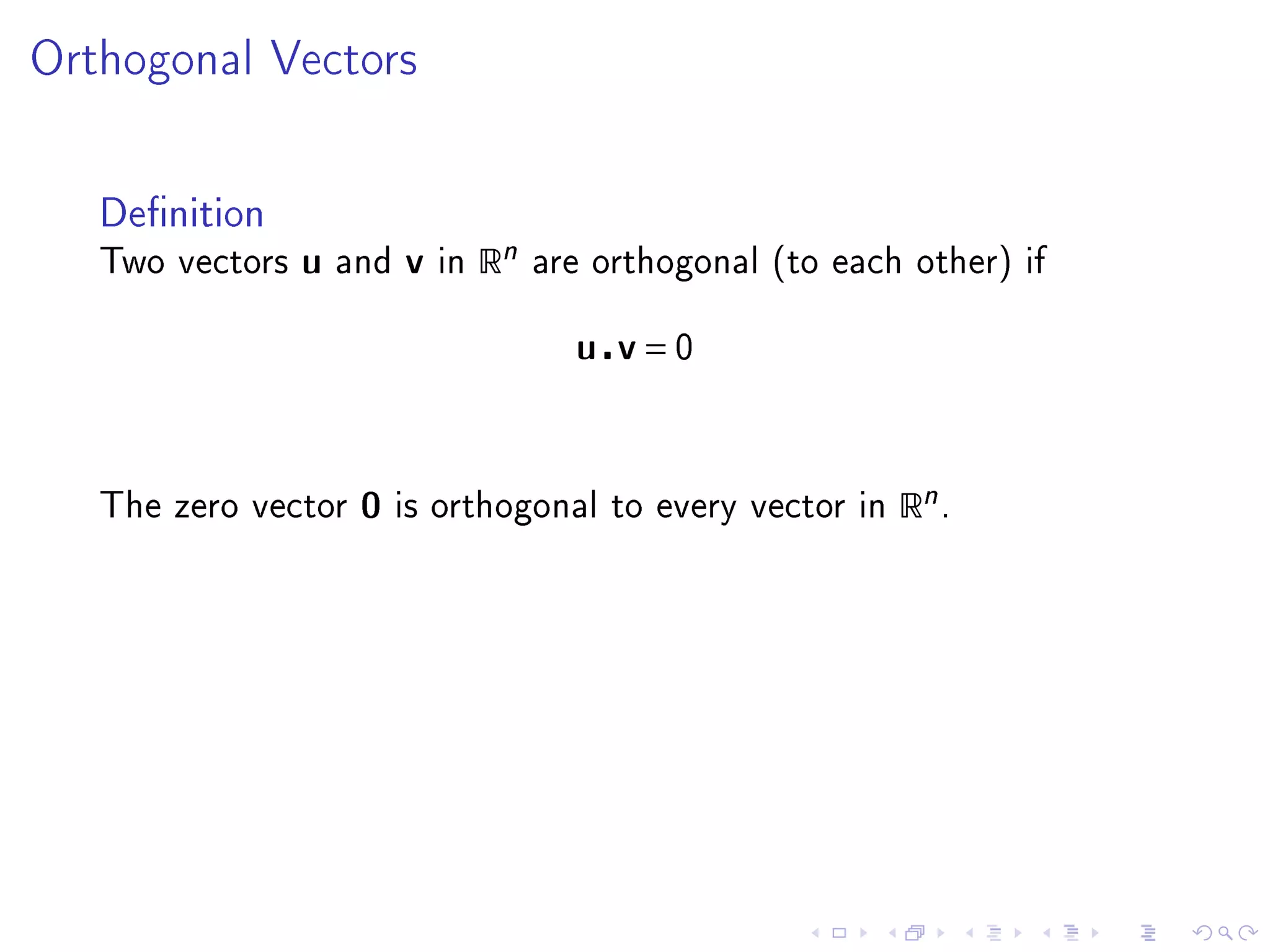

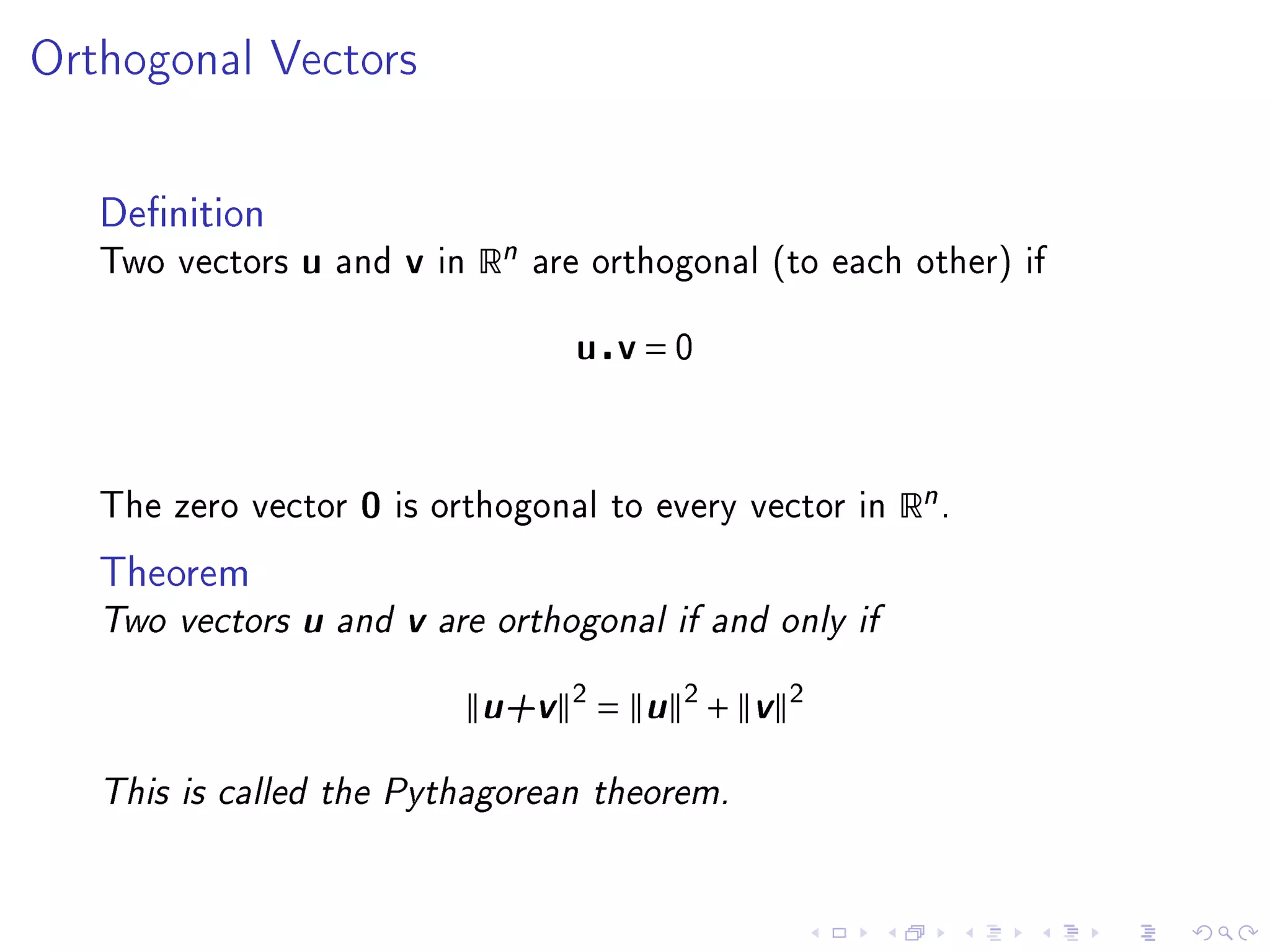

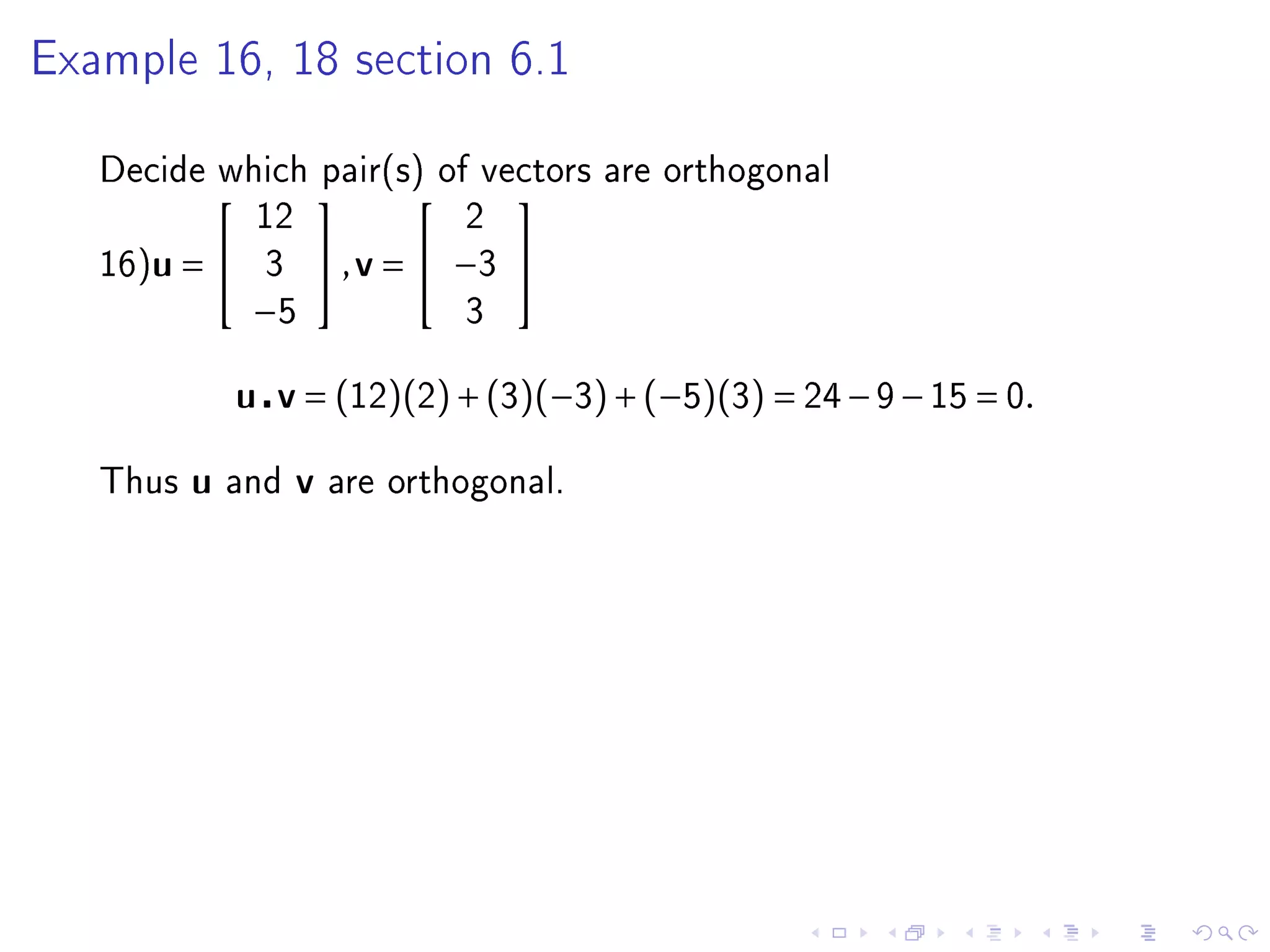

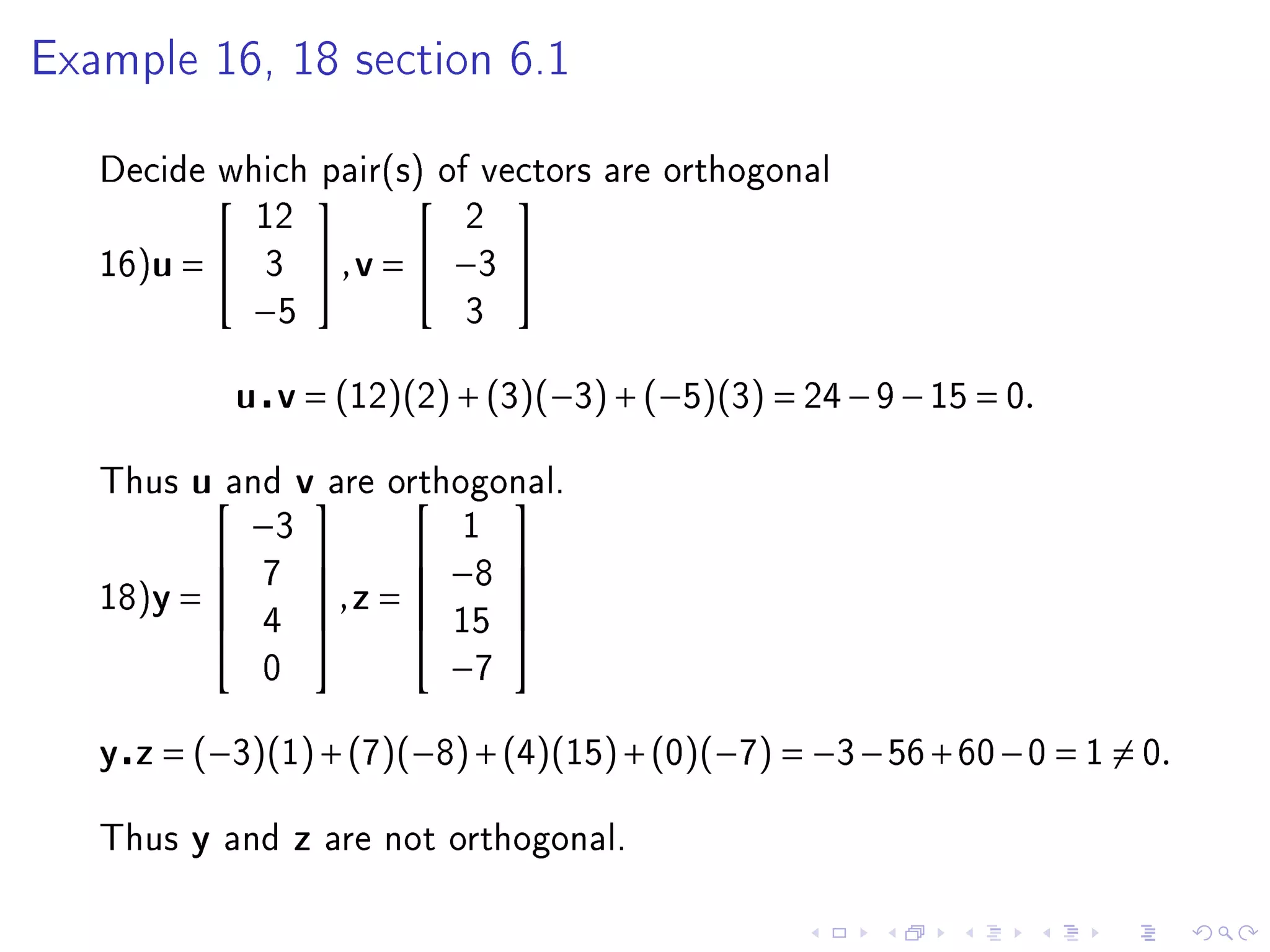

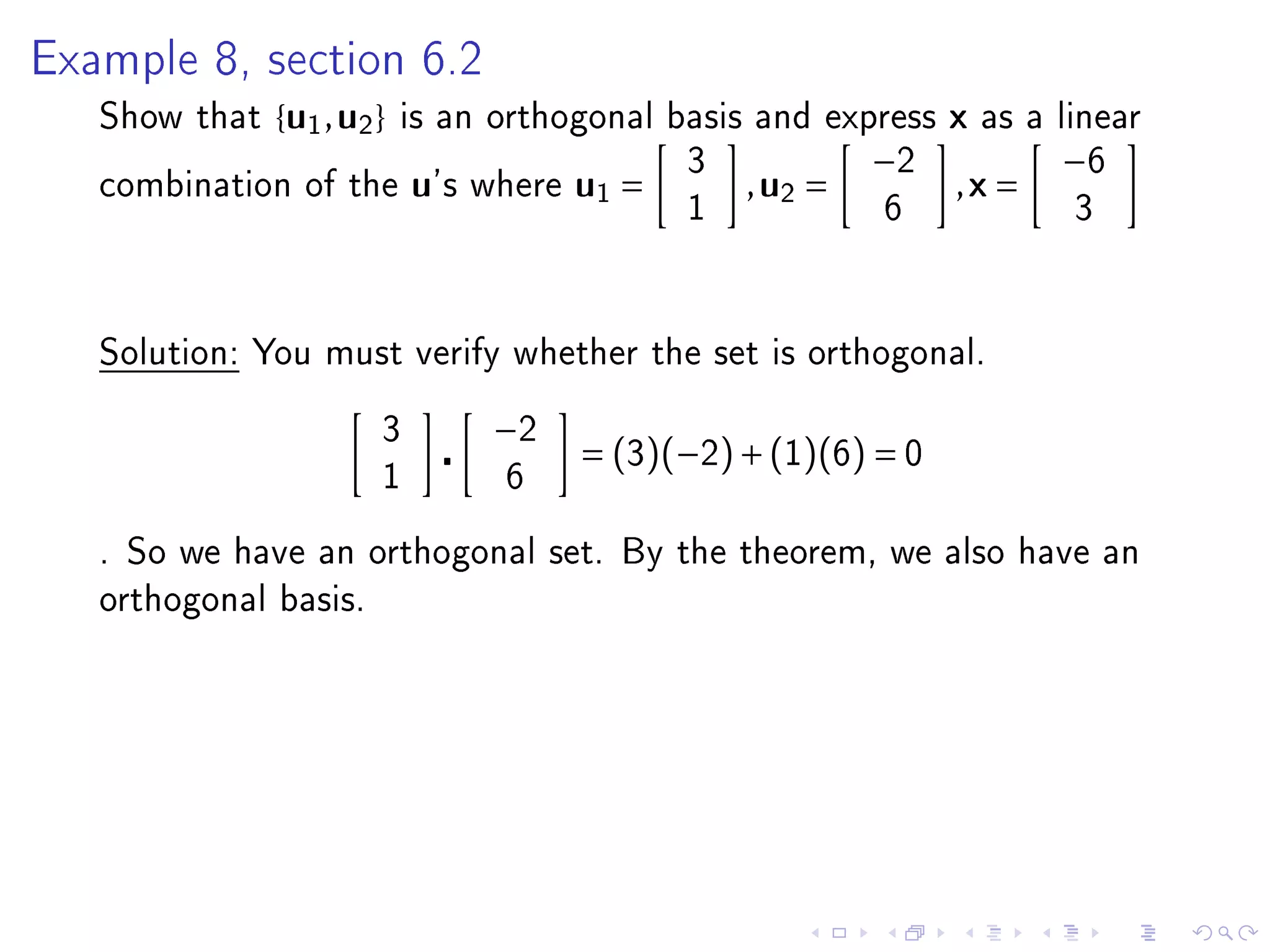

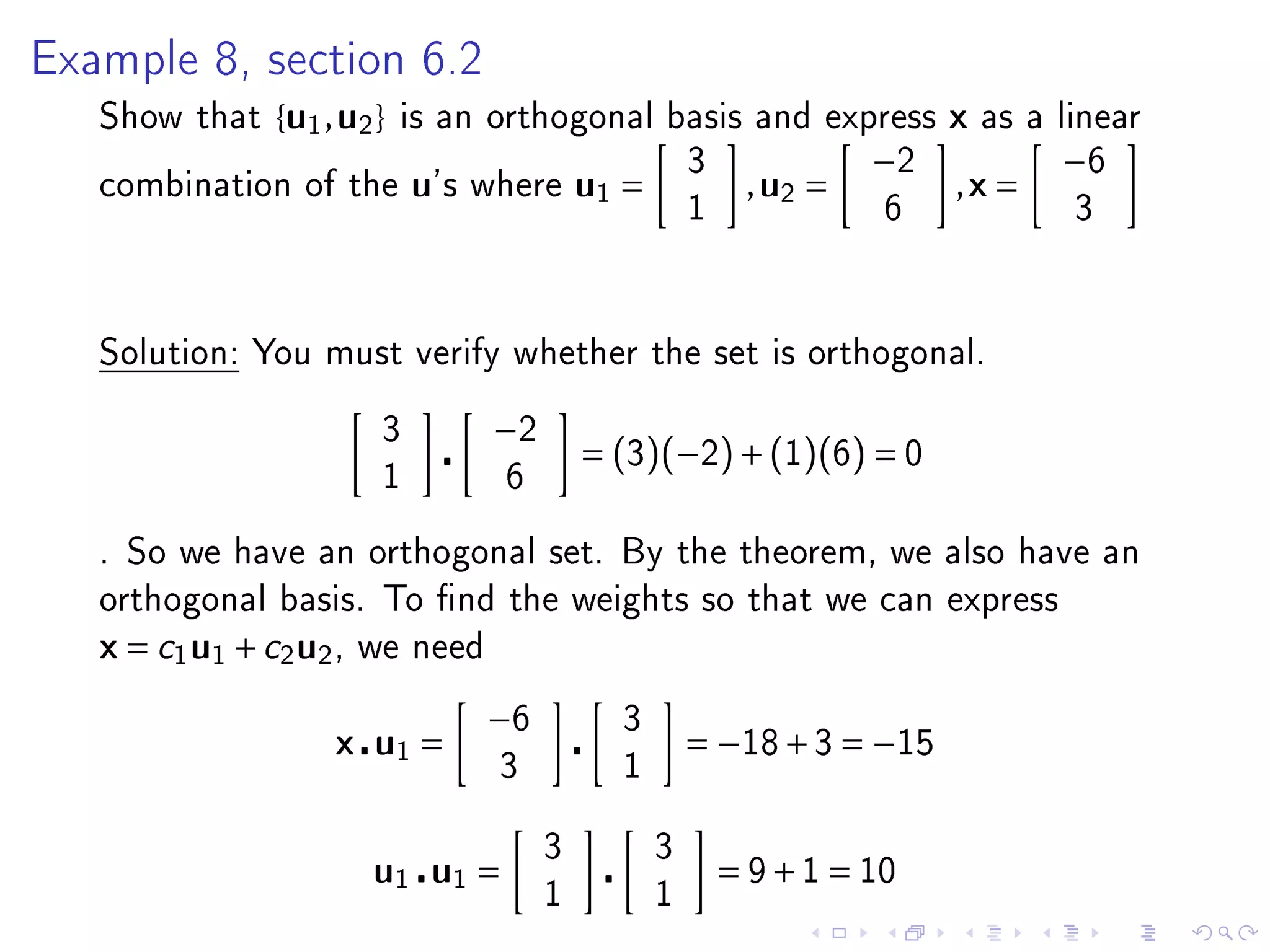

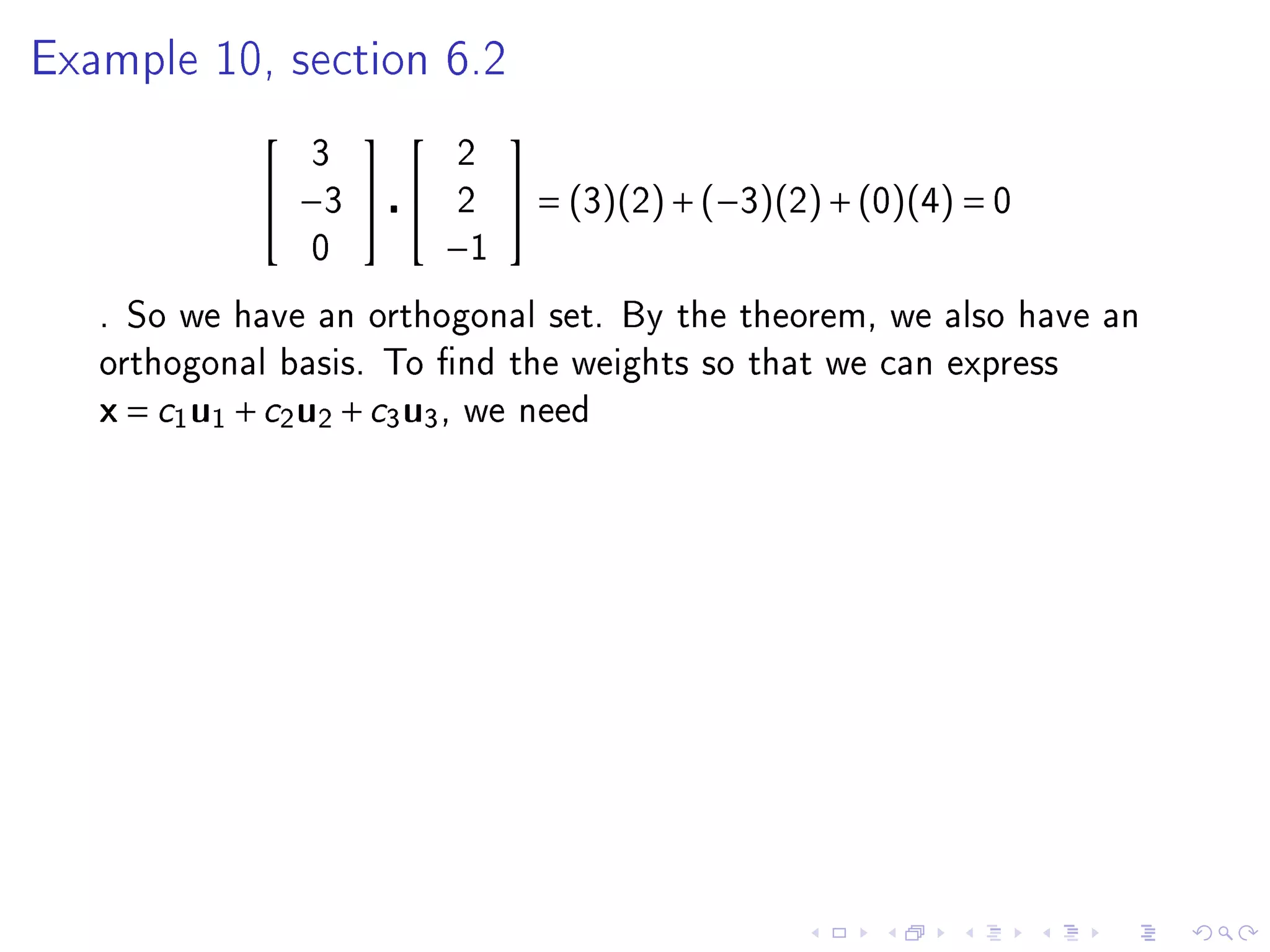

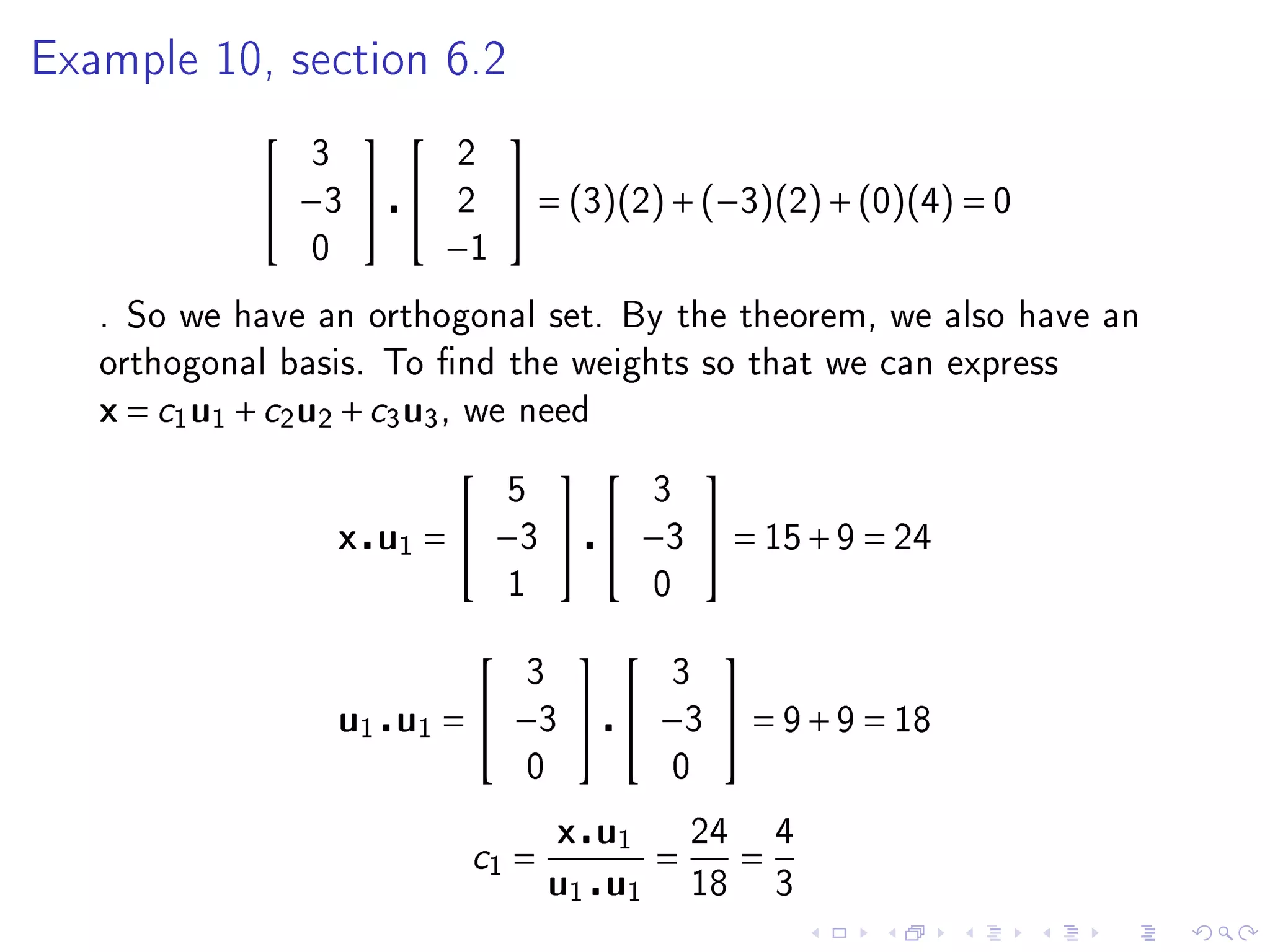

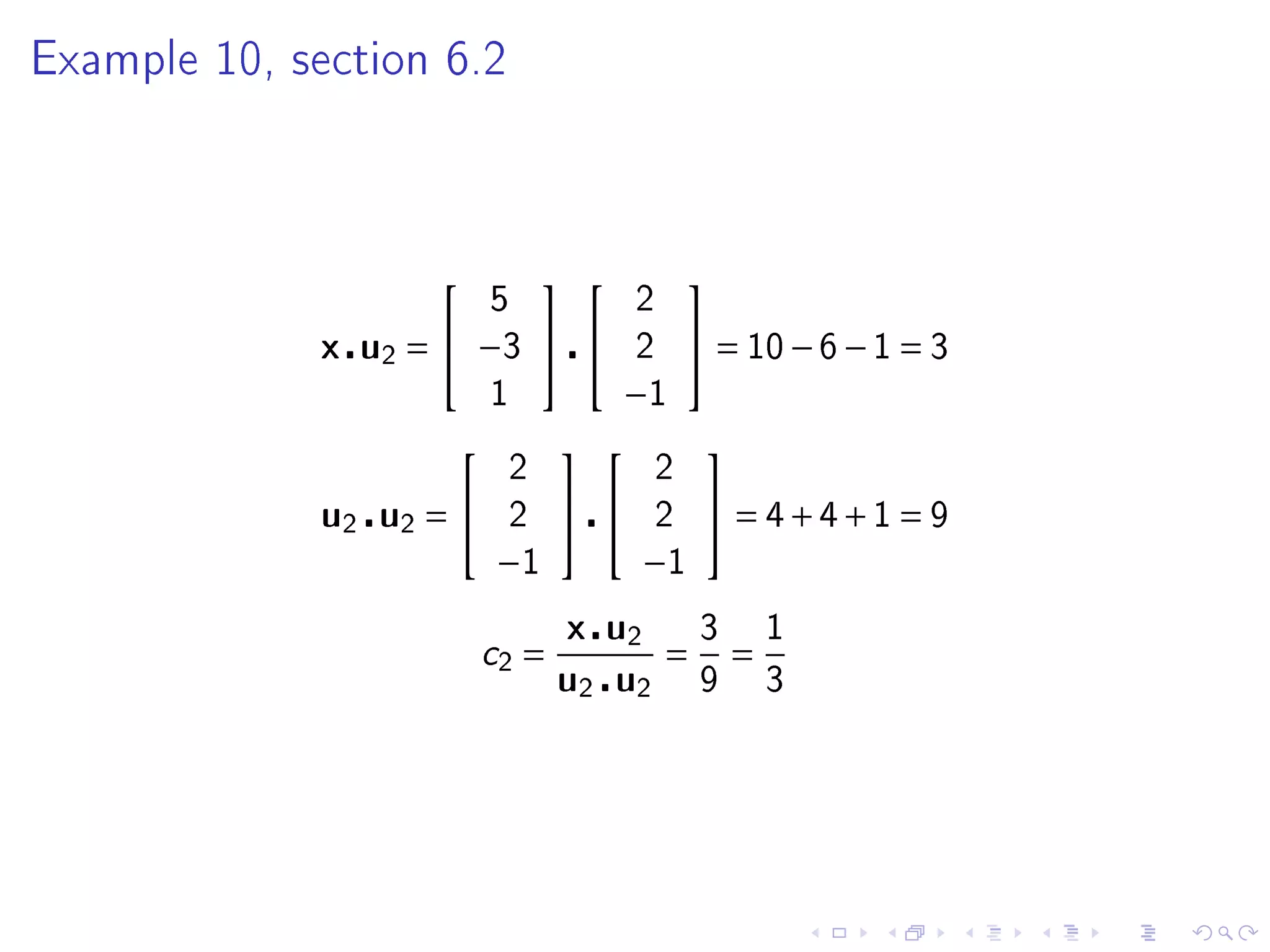

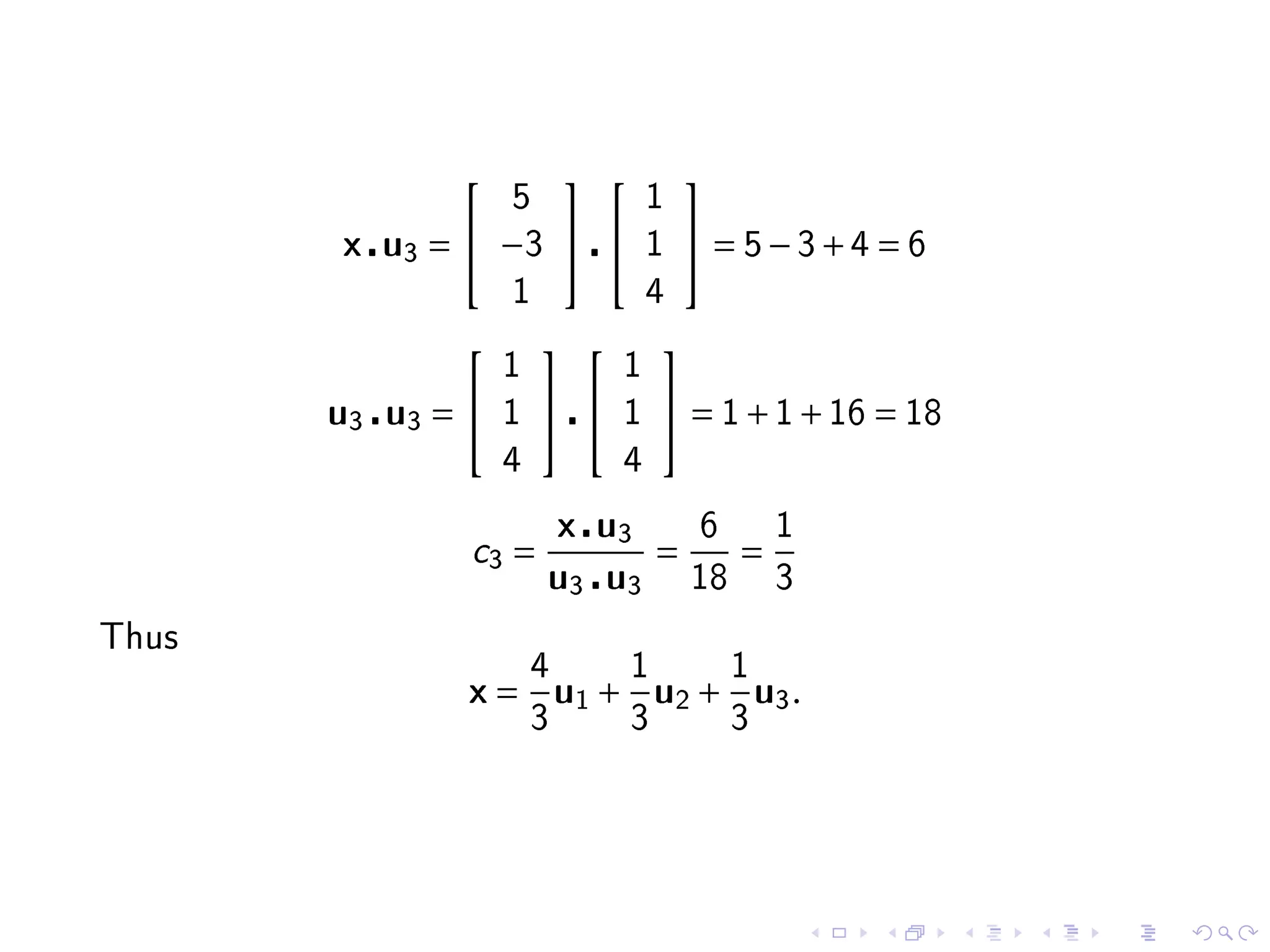

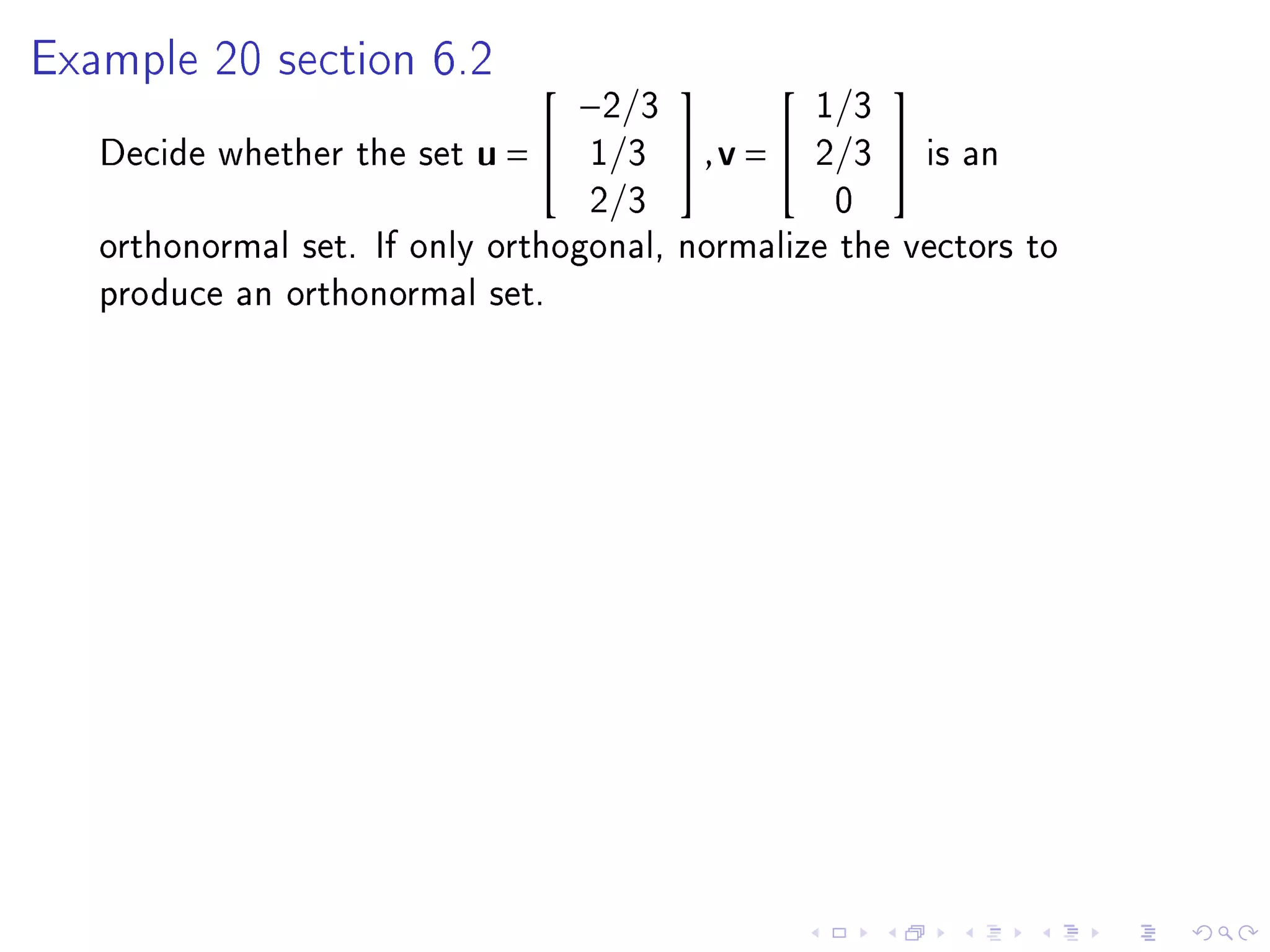

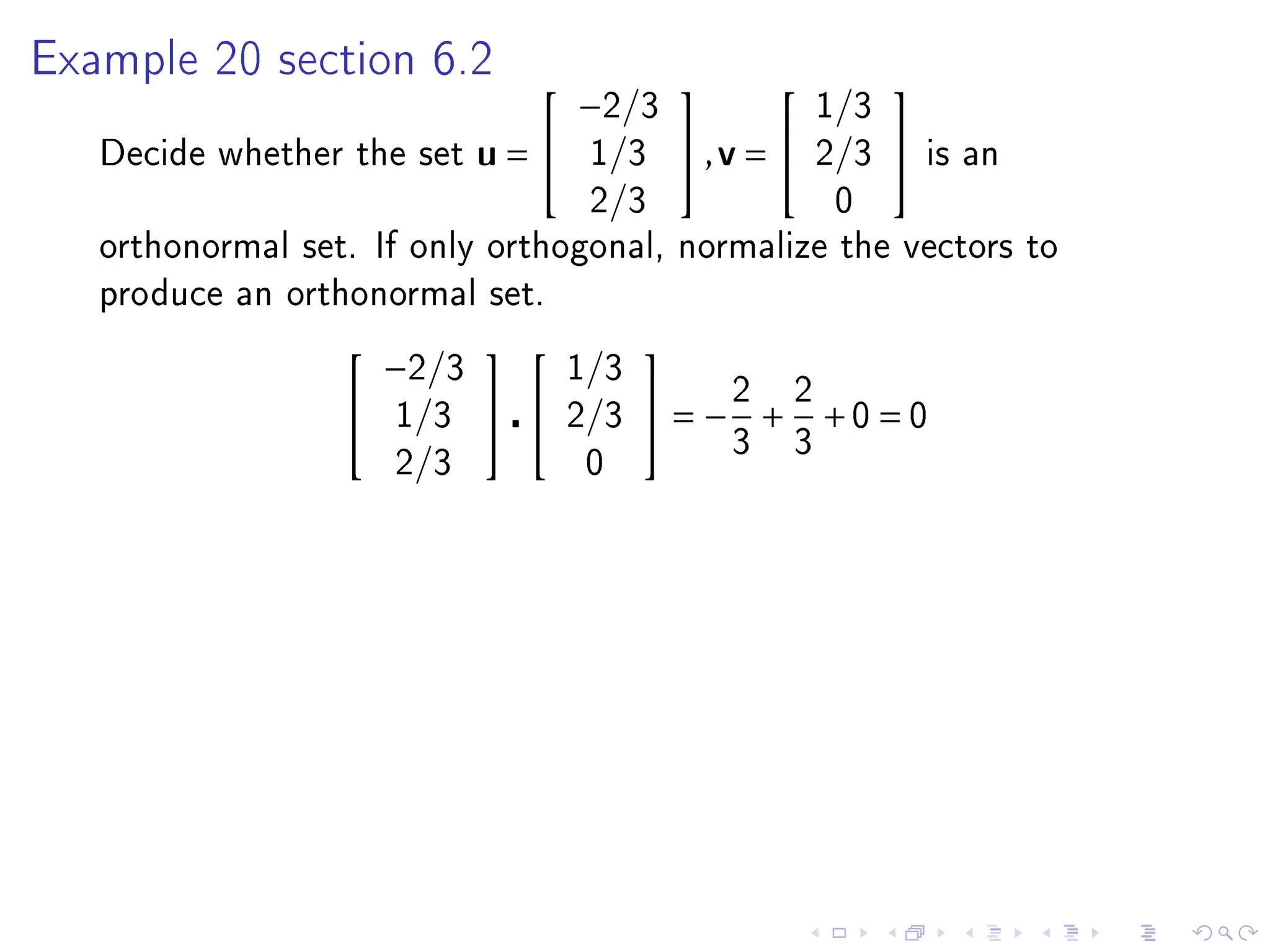

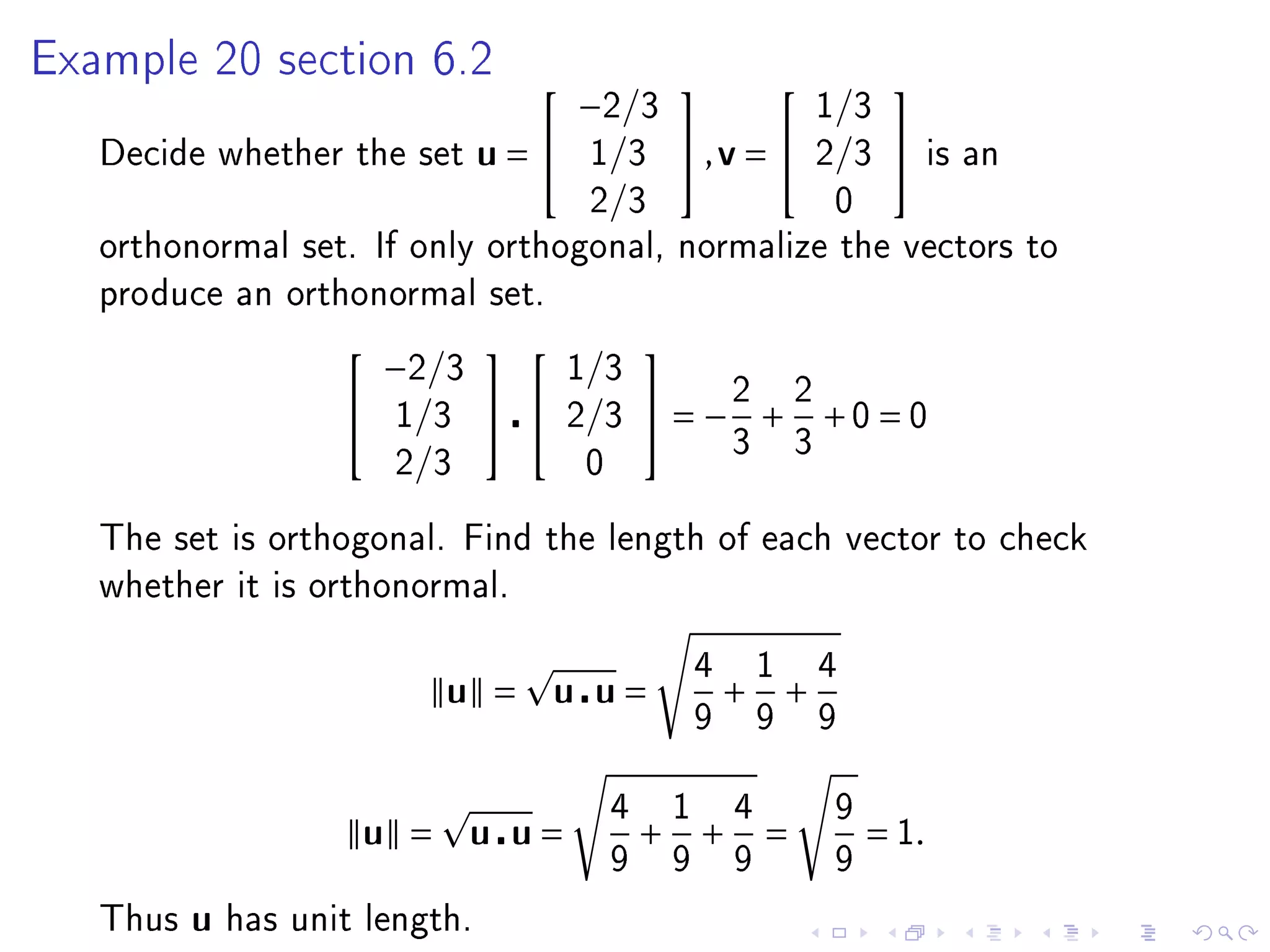

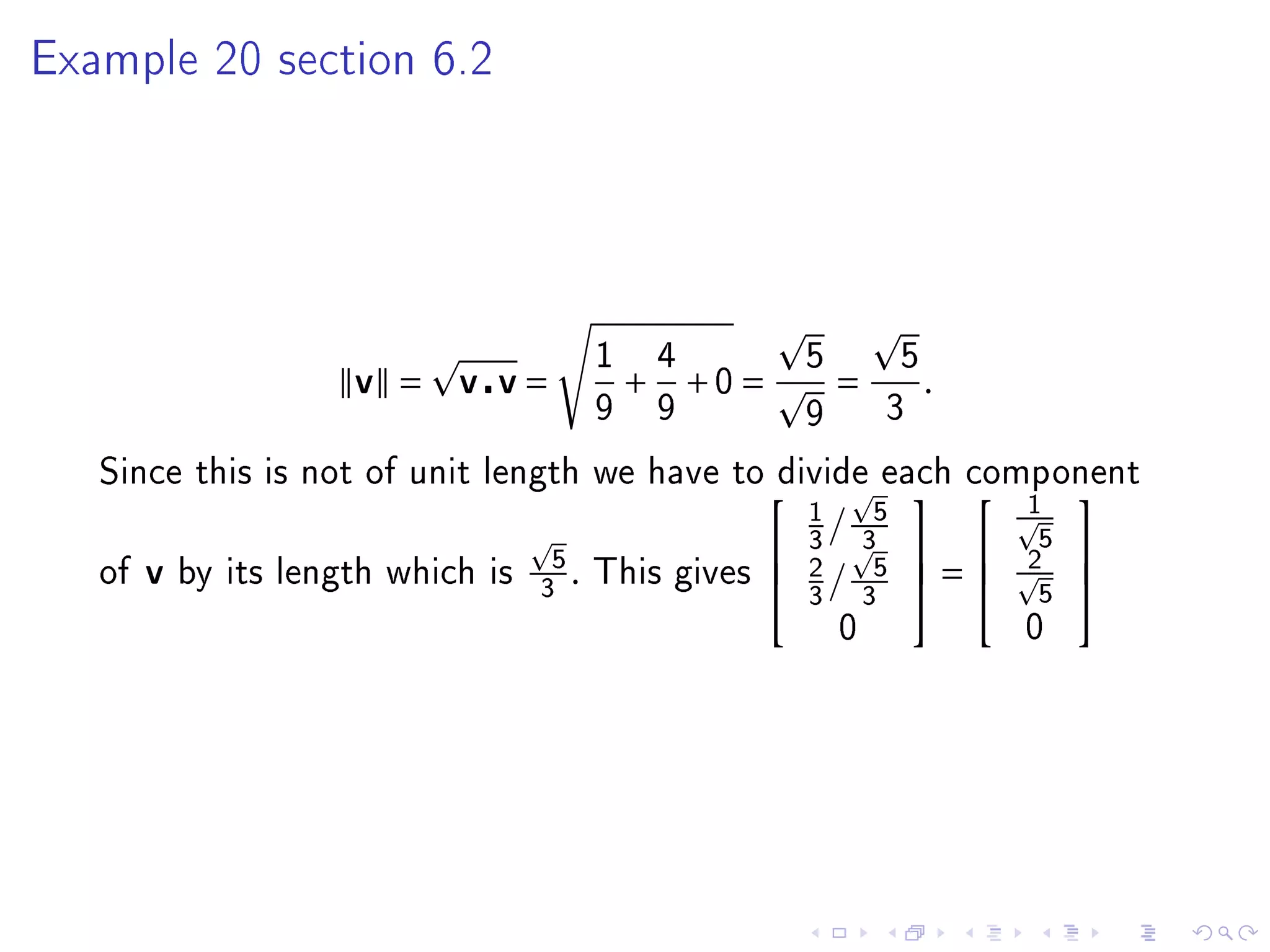

- The inner product of two vectors u and v in Rn is defined as their dot product, which is the sum of the component-wise products of corresponding elements in u and v.