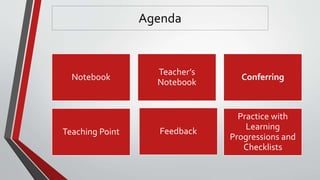

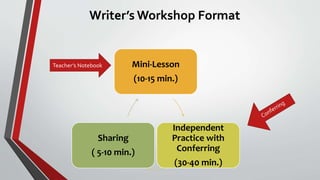

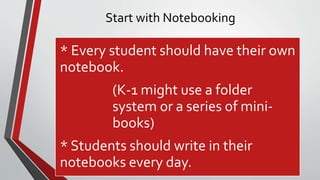

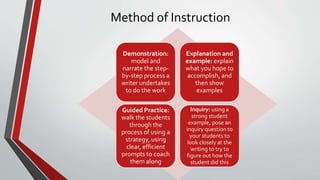

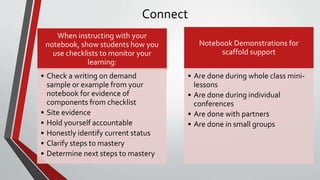

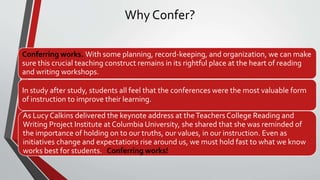

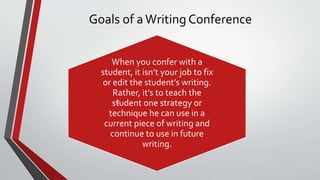

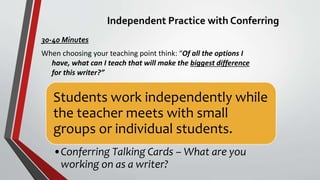

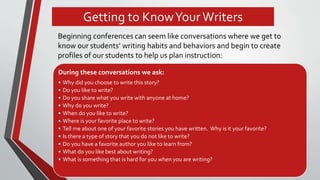

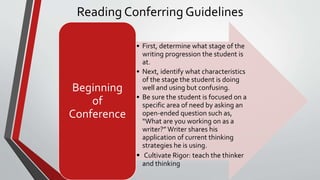

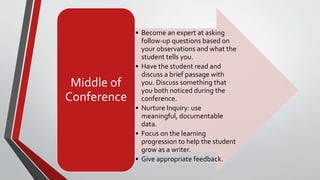

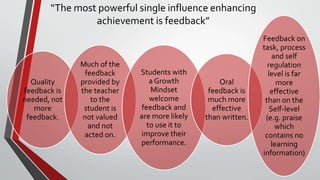

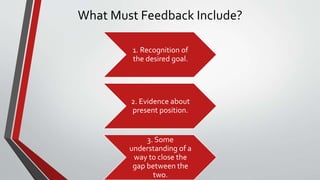

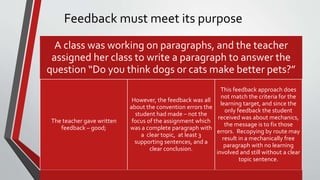

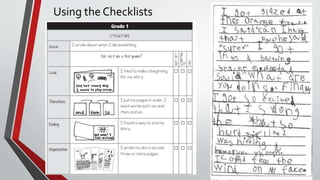

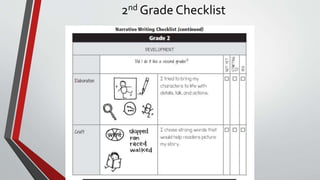

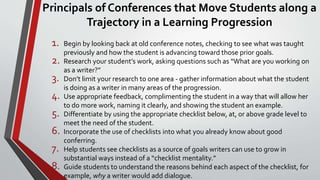

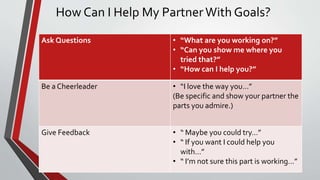

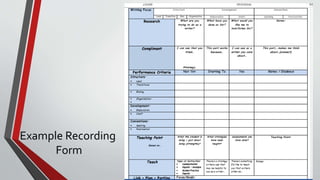

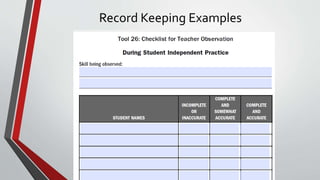

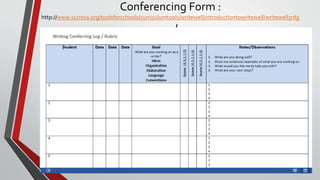

This document provides information about writing workshops, conferring with students, and using checklists to guide writing instruction and monitor student progress. It discusses the key components of writing workshops, including mini-lesssons, independent writing time with teacher conferencing, and sharing. The purpose and goals of writing conferences are outlined. Checklists for different grade levels are provided as tools to track student learning. Strategies for effective conferring, such as asking questions, giving feedback, and setting goals, are also presented.