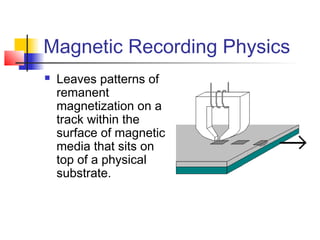

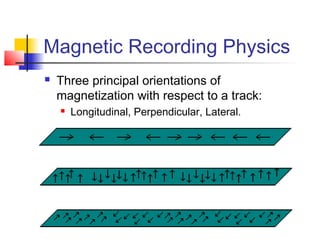

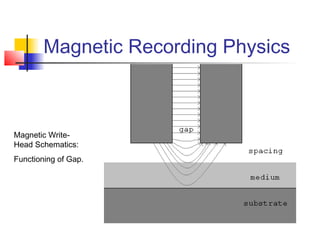

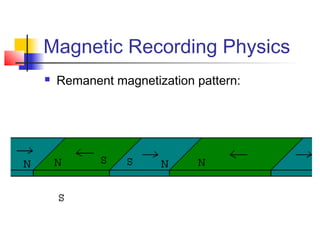

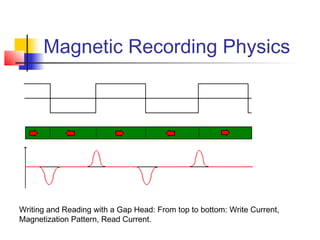

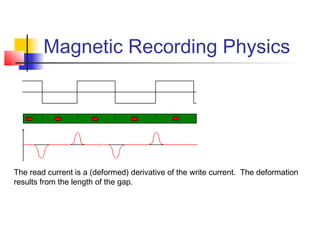

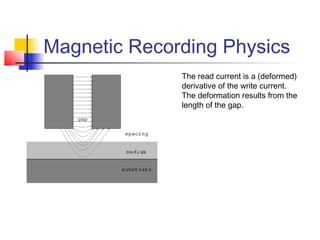

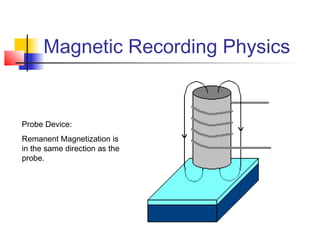

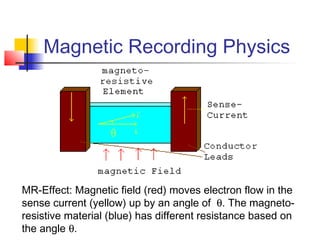

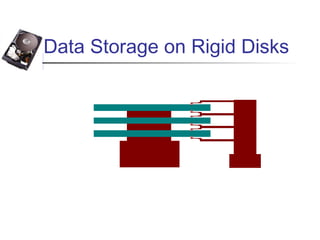

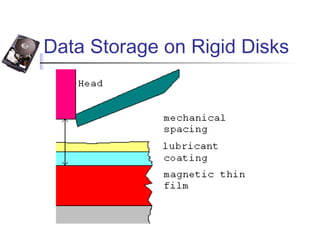

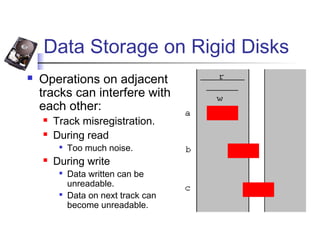

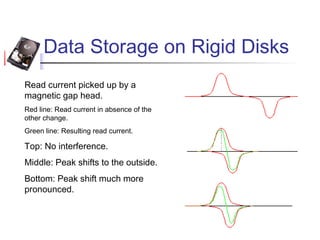

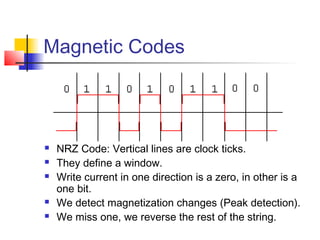

Magnetic recording leaves patterns of magnetization on magnetic media to store data. Tracks are formed as the read/write head passes over the media. There are three main orientations for magnetization: longitudinal, perpendicular, and lateral. Longitudinal recording uses a ring-shaped electromagnet head with a gap to magnetize the media as it moves under the head. Changes in the current passing through the head leave spatial variations in magnetization along the track. Modern drives use magneto-resistive read heads that directly sense the magnetic flux from the tracks. Error correcting codes and redundant data help ensure reliable storage despite defects and noise sources that can cause errors.