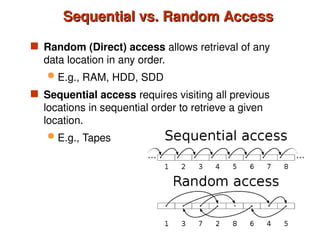

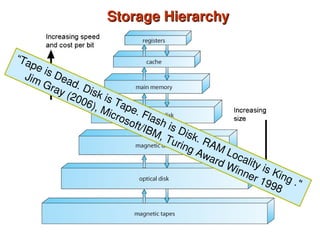

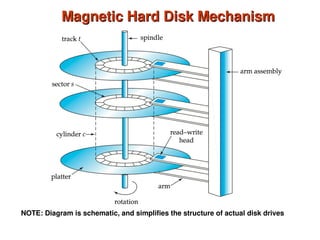

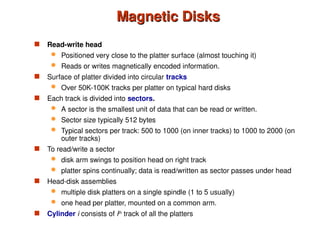

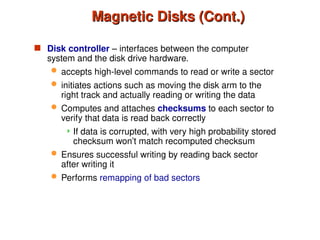

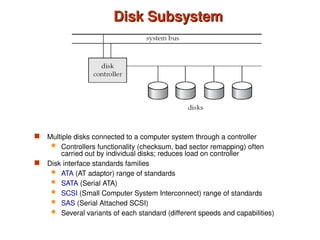

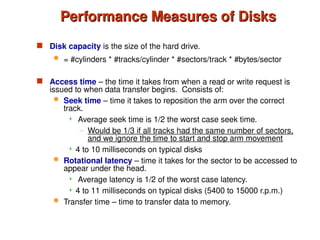

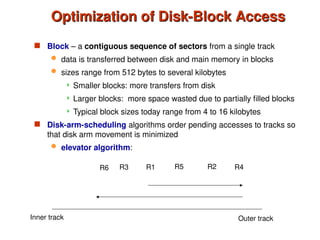

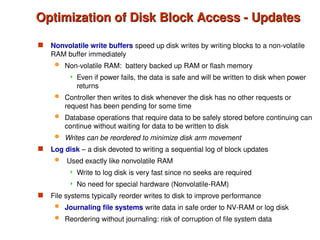

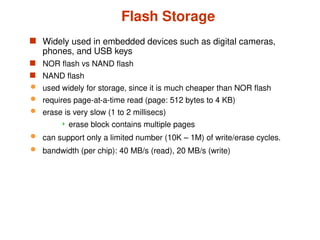

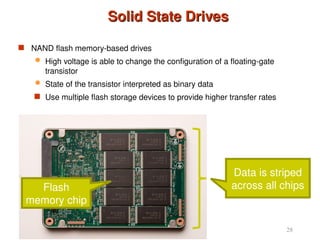

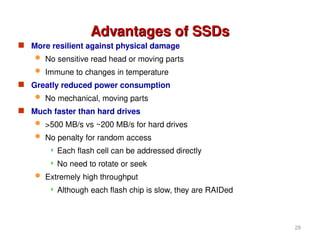

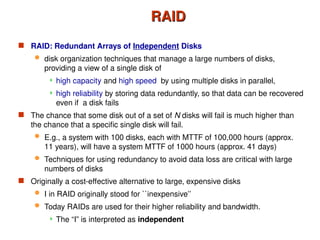

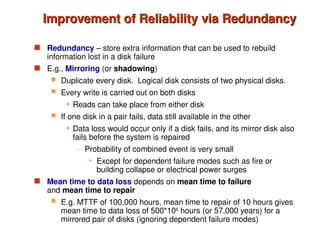

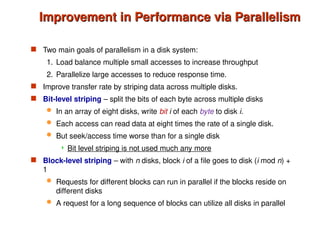

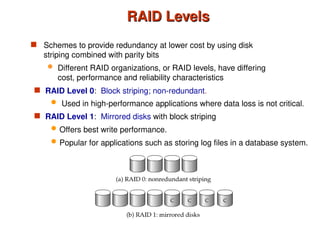

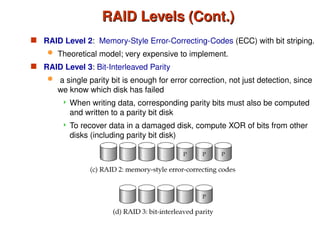

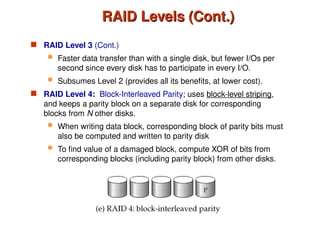

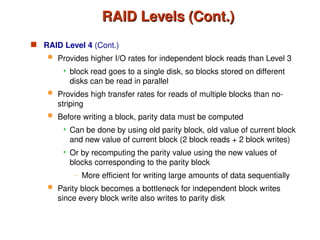

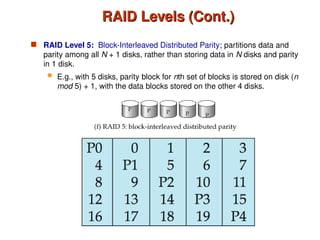

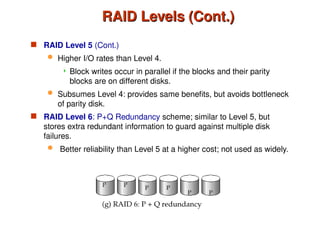

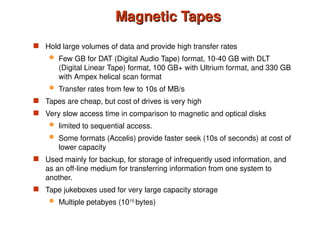

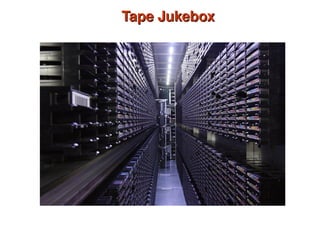

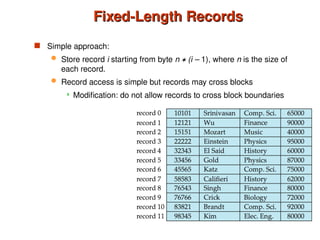

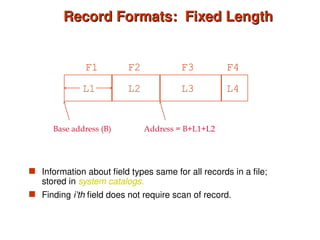

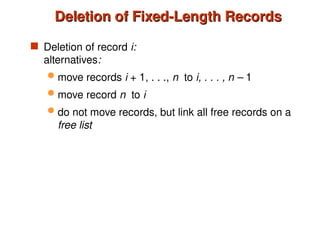

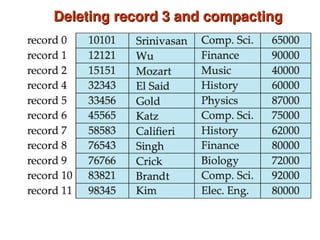

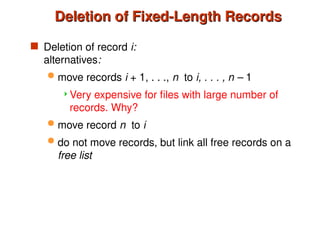

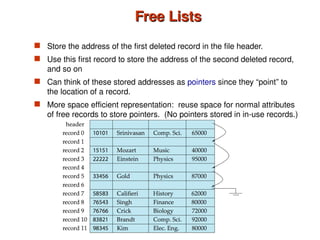

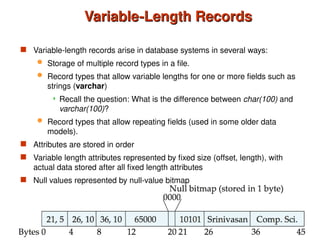

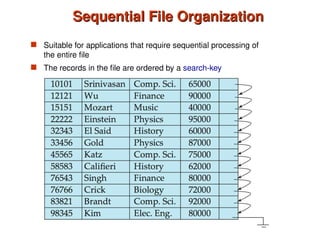

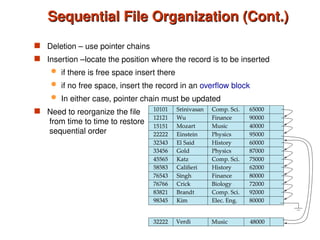

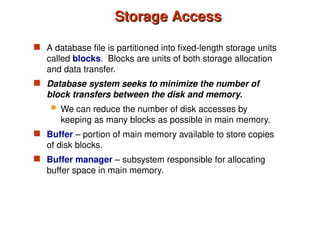

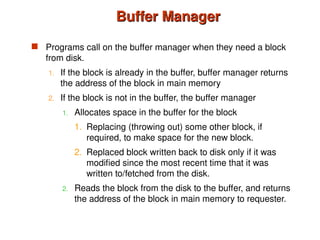

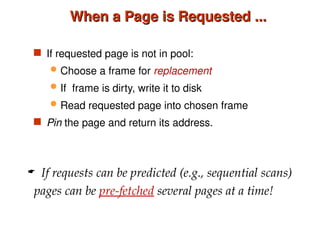

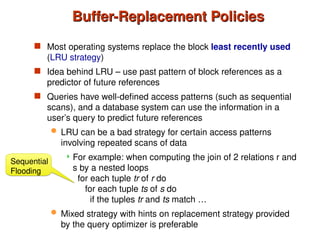

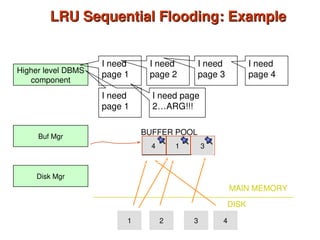

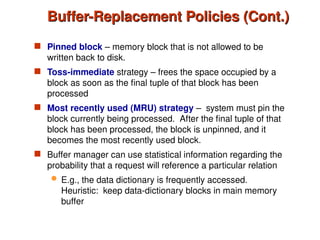

Chapter 10 of 'Database System Concepts' covers storage and file structures, detailing various physical storage media including magnetic disks, RAID, and tertiary storage. It discusses performance measures, organization of records, disk access methods, and the hierarchical relationship between storage types (primary, secondary, and tertiary). Furthermore, the chapter explains optimizations for disk block access and the principles of redundancy and parallelism in RAID systems.