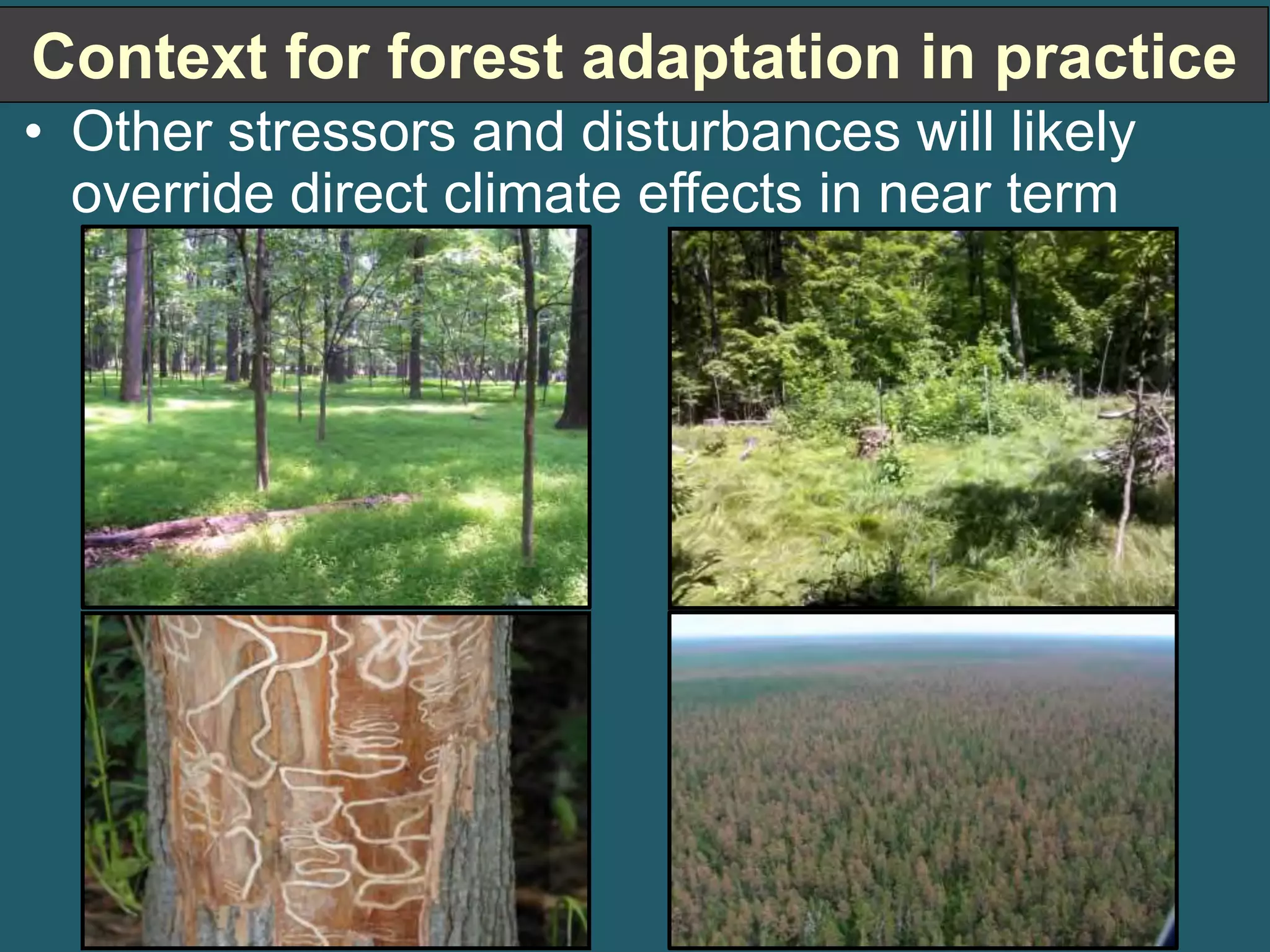

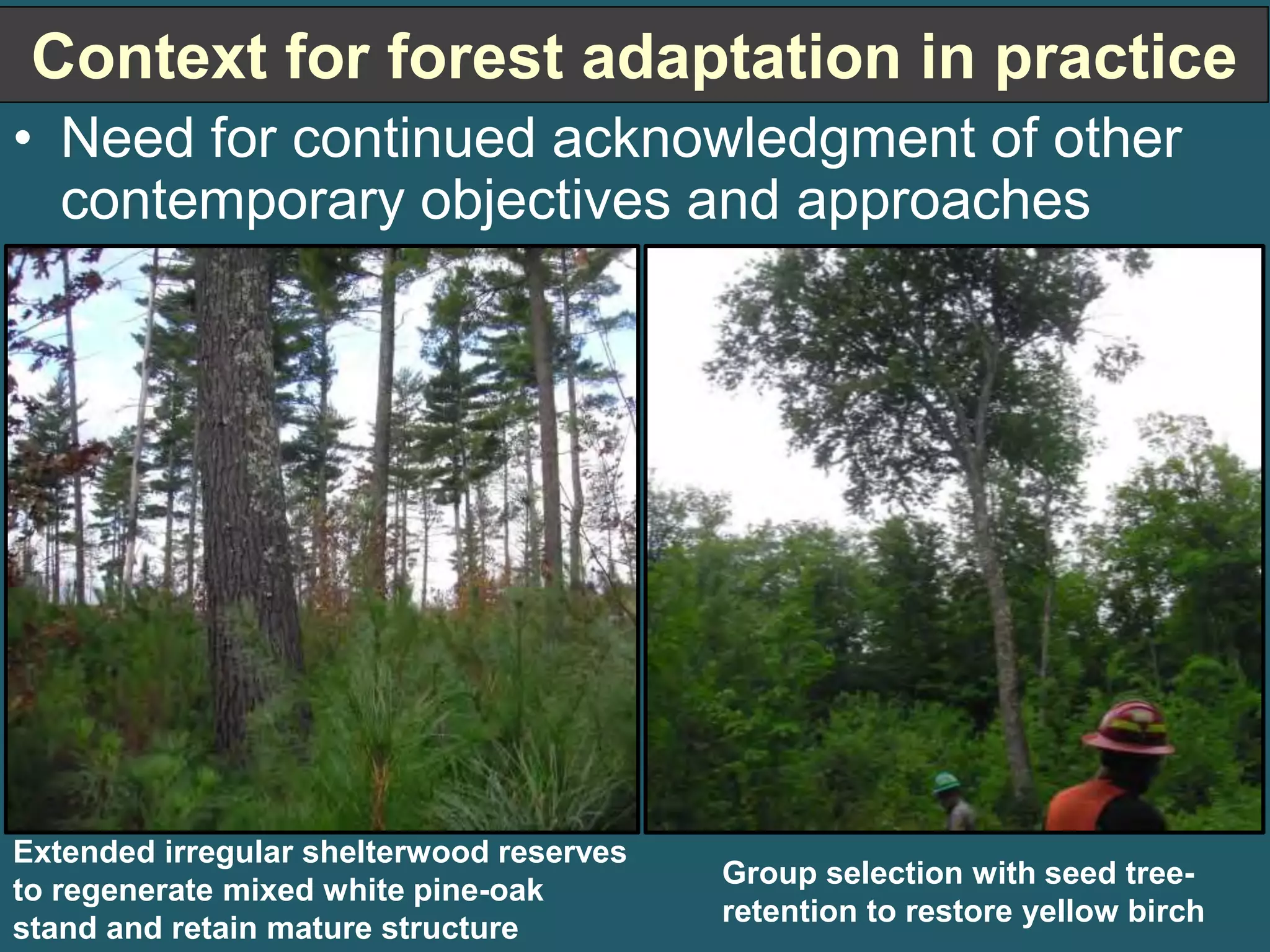

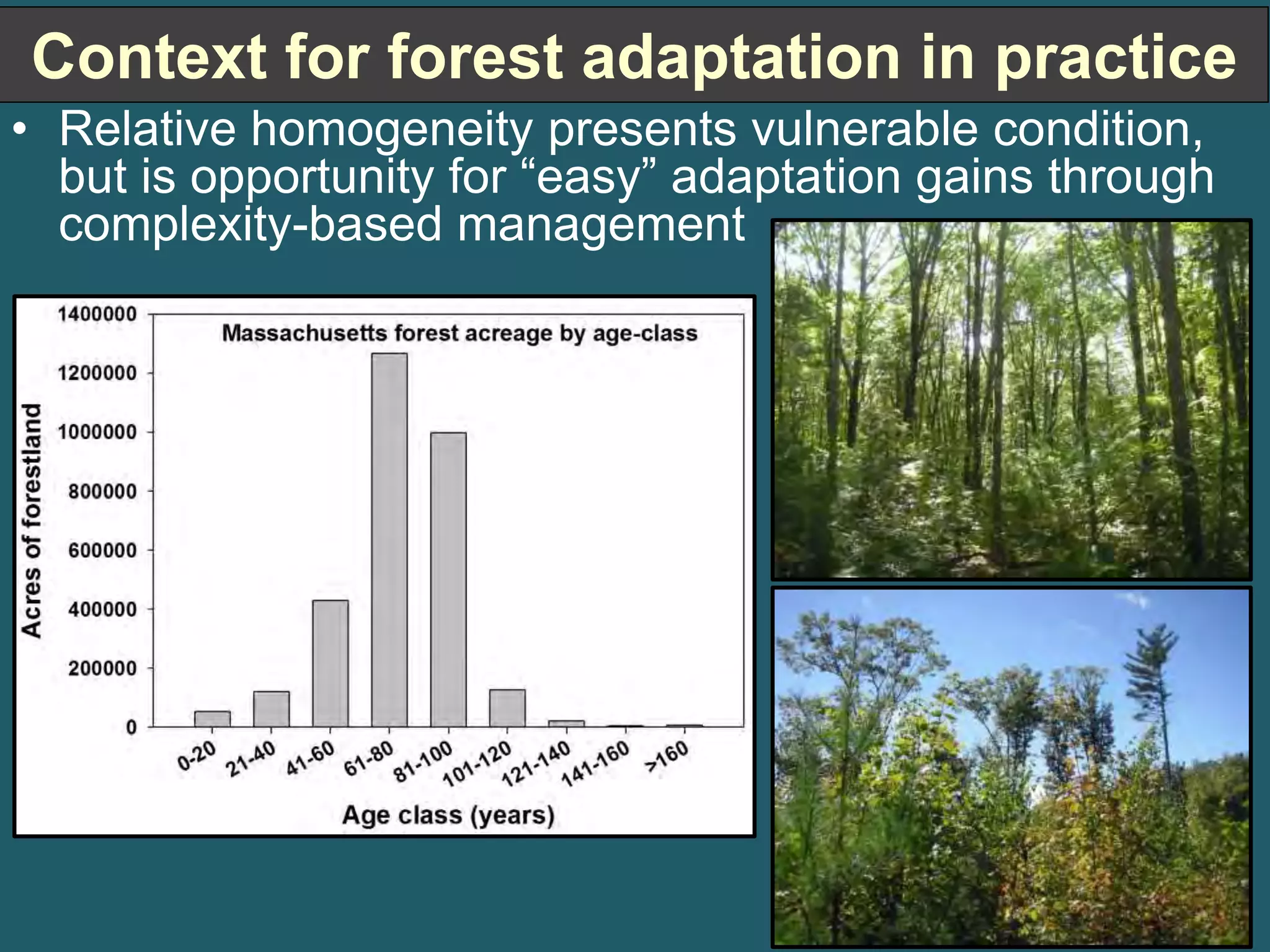

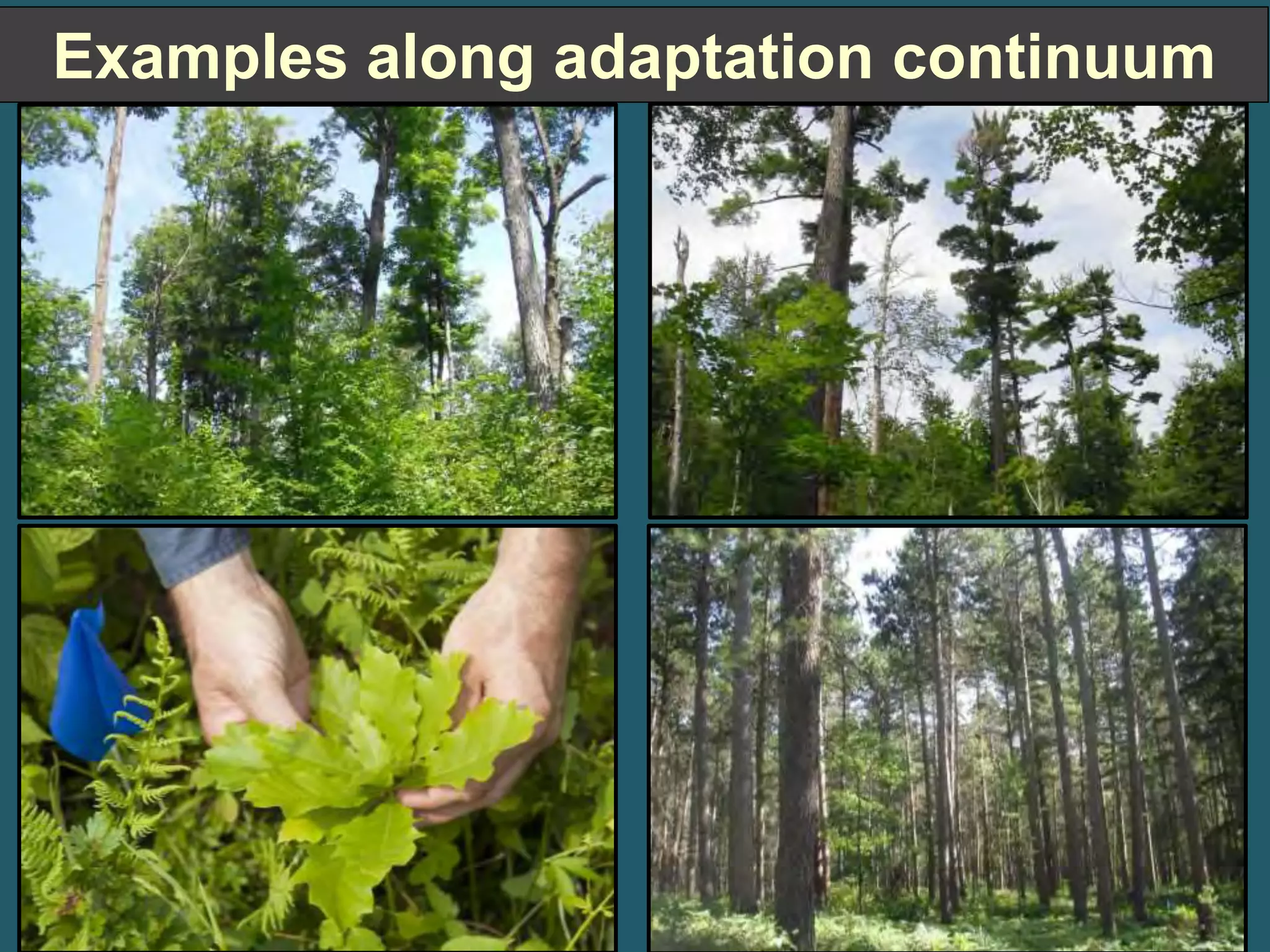

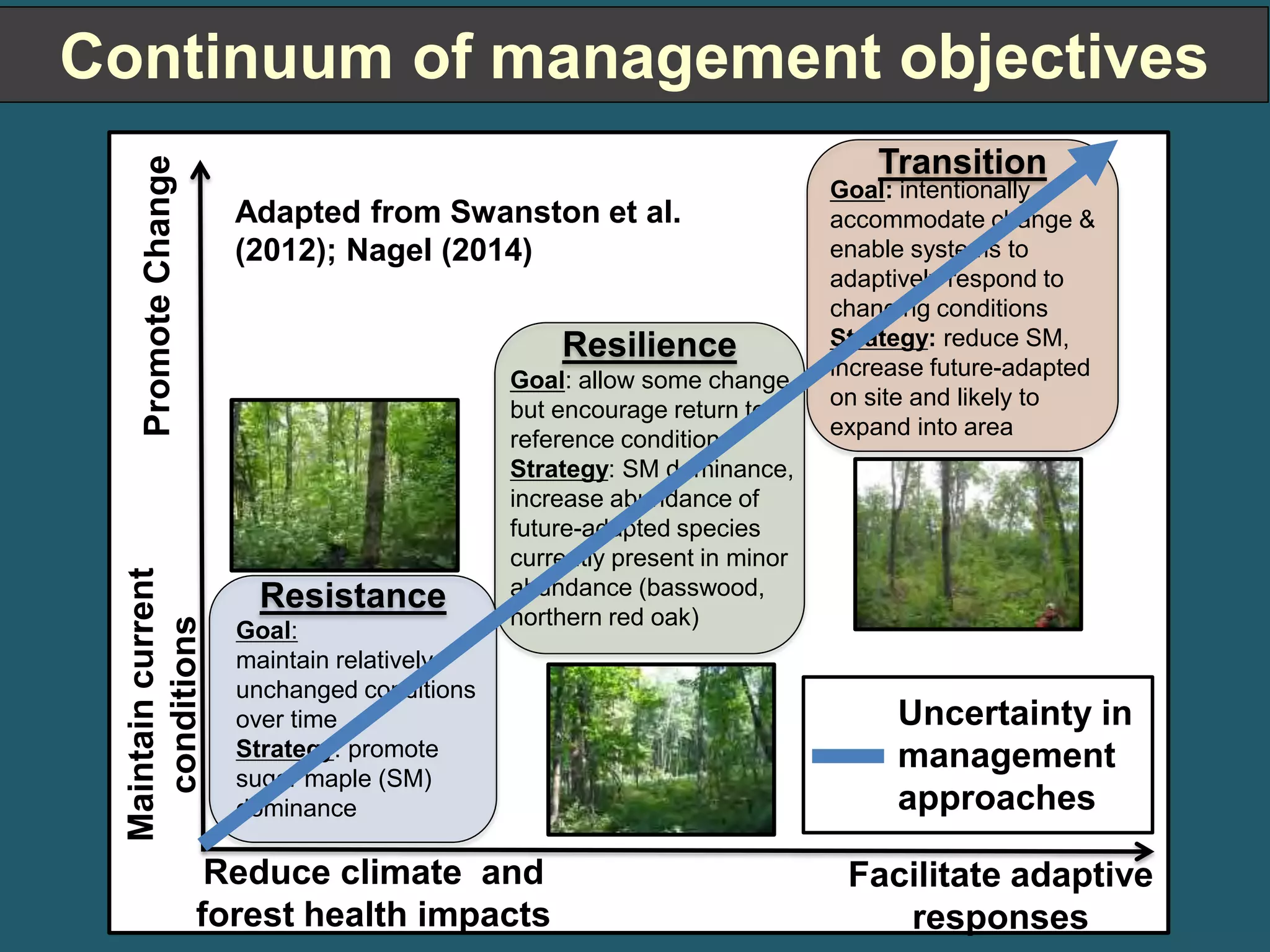

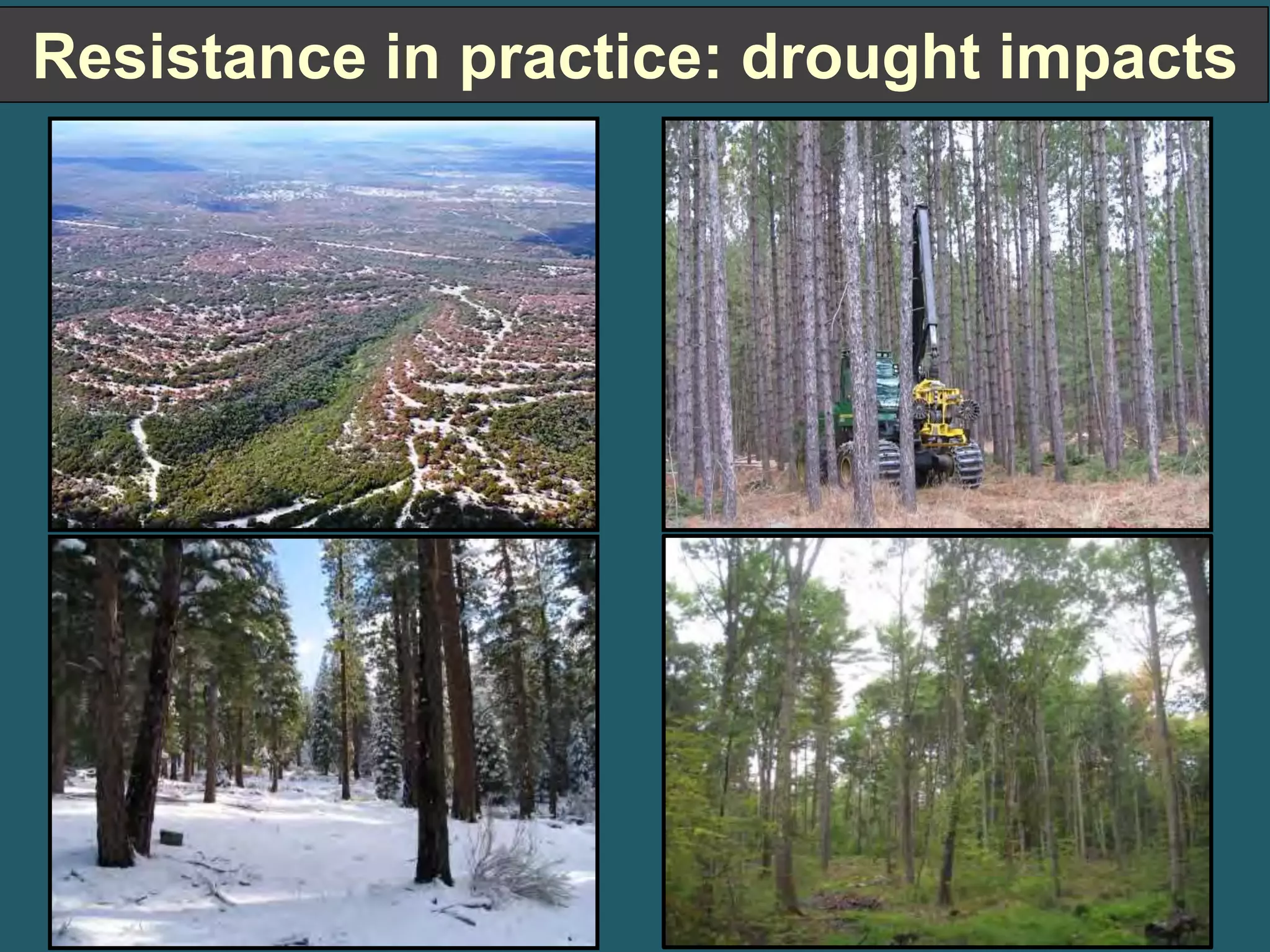

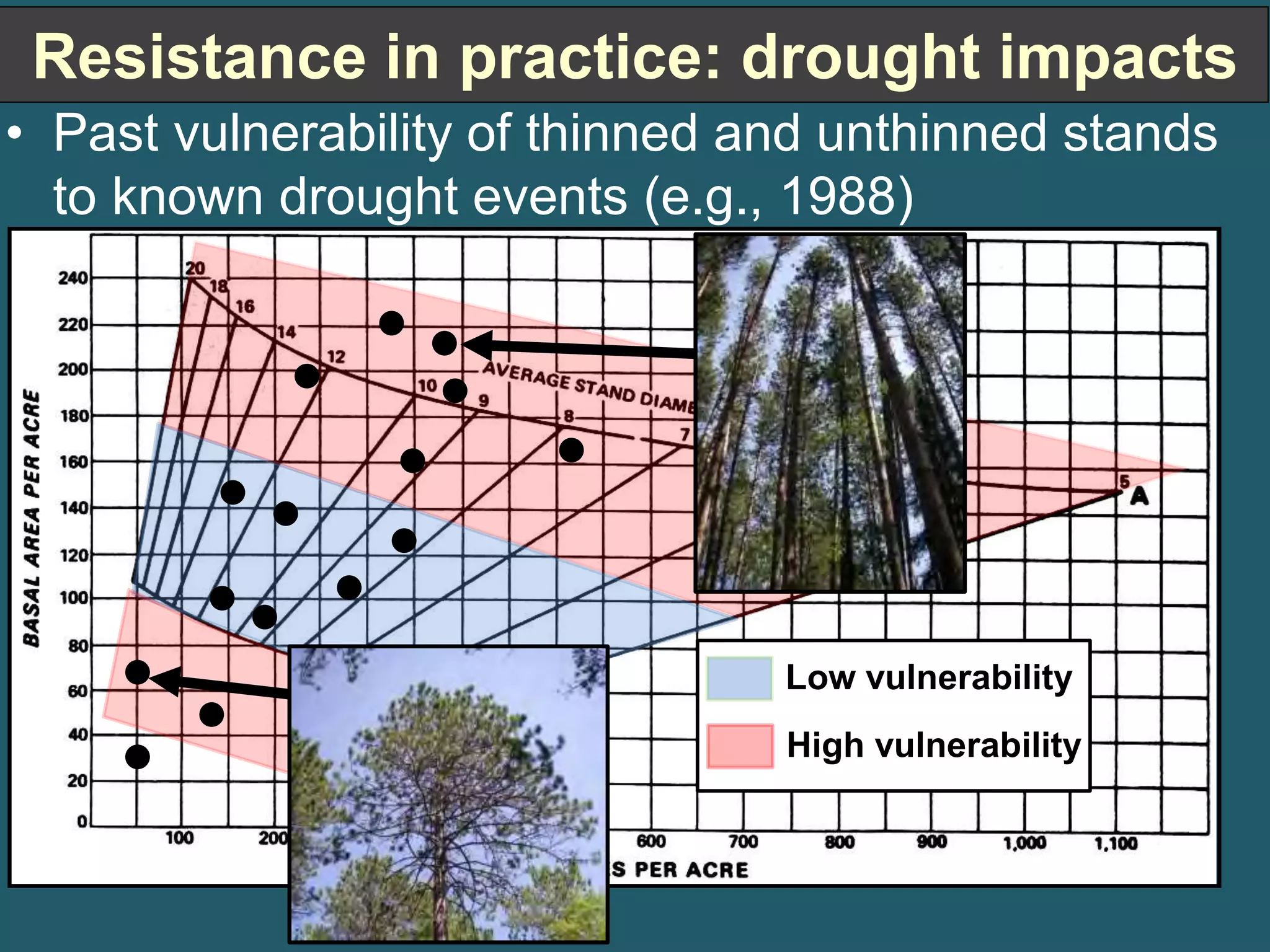

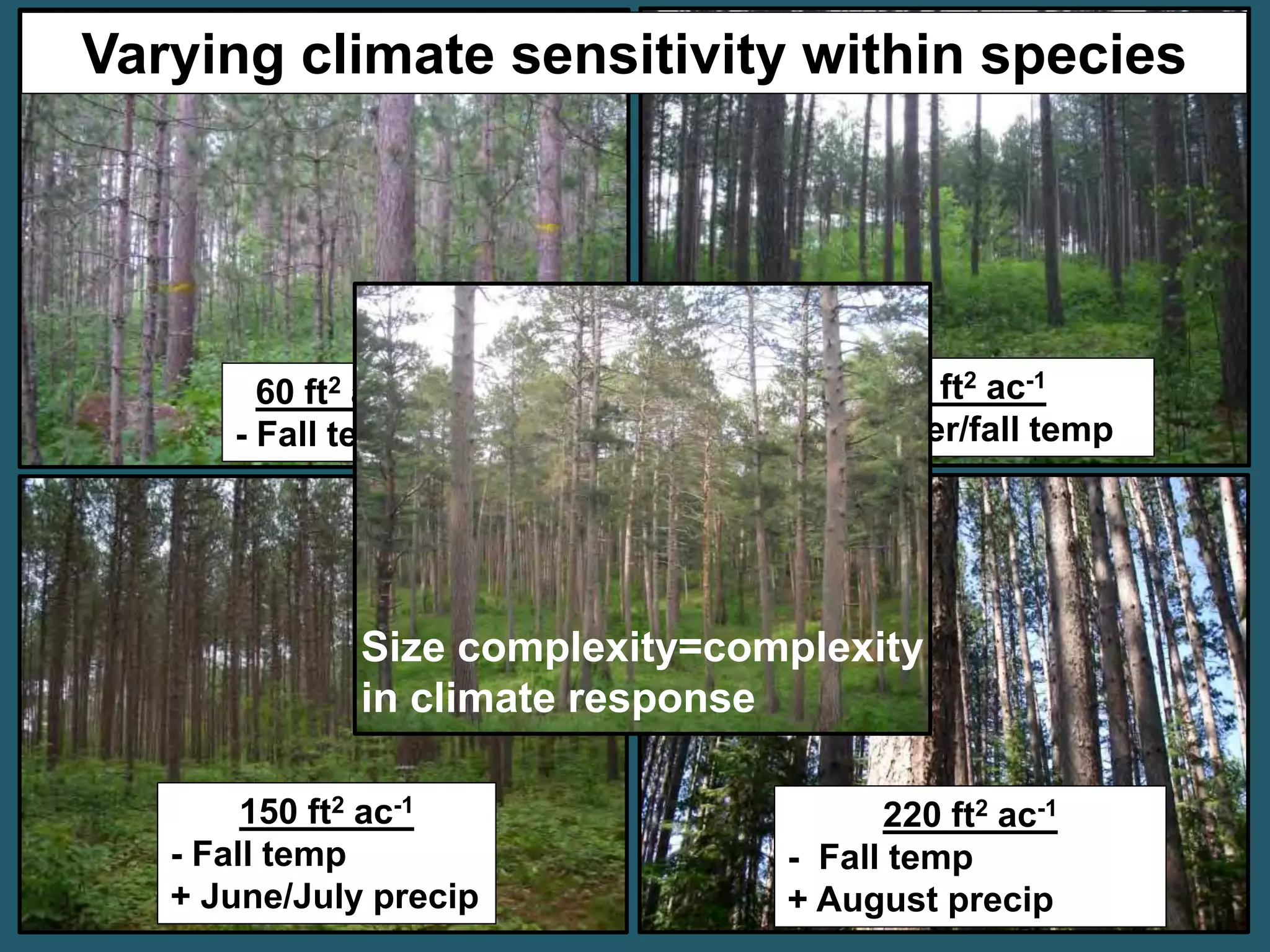

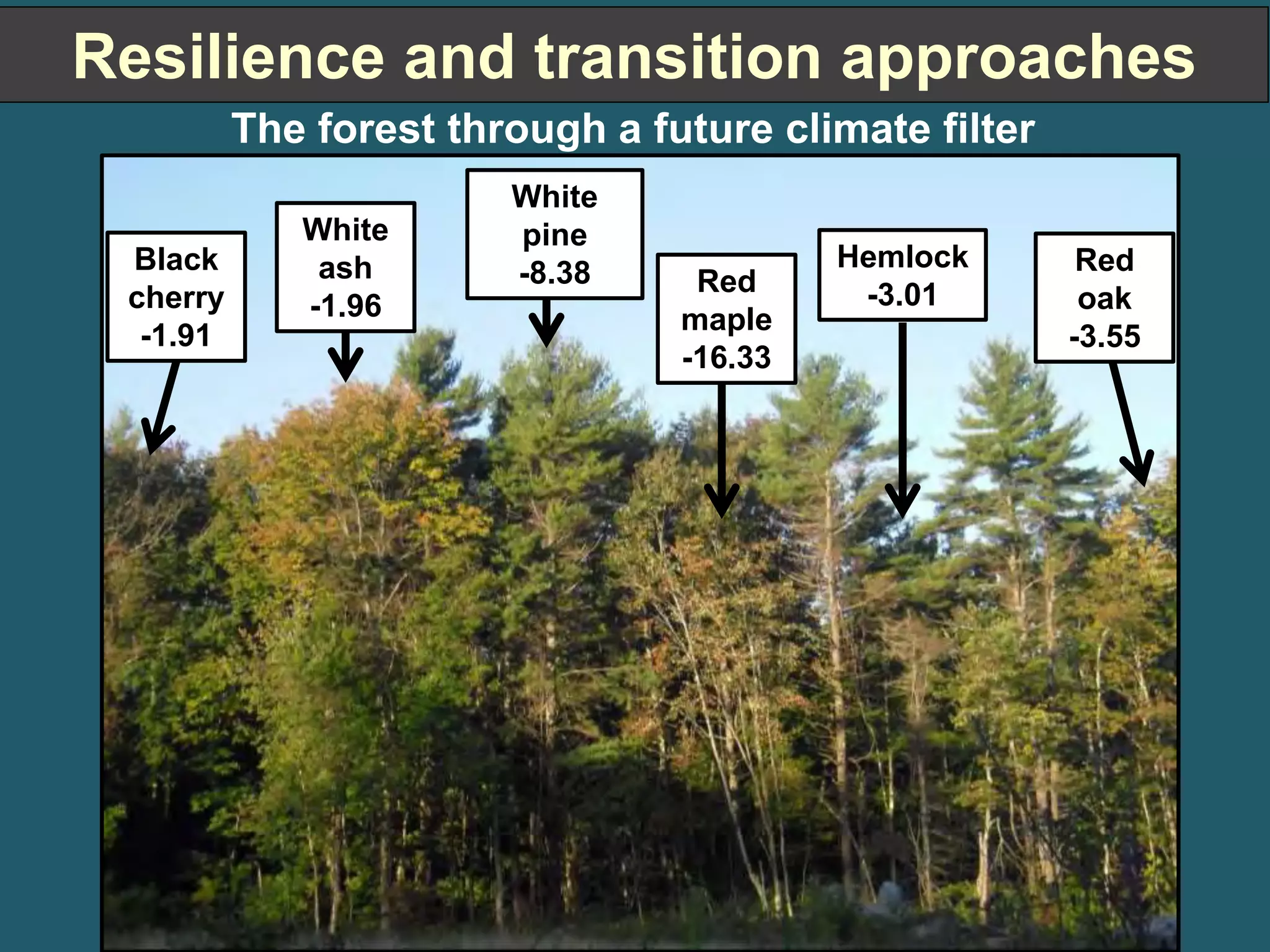

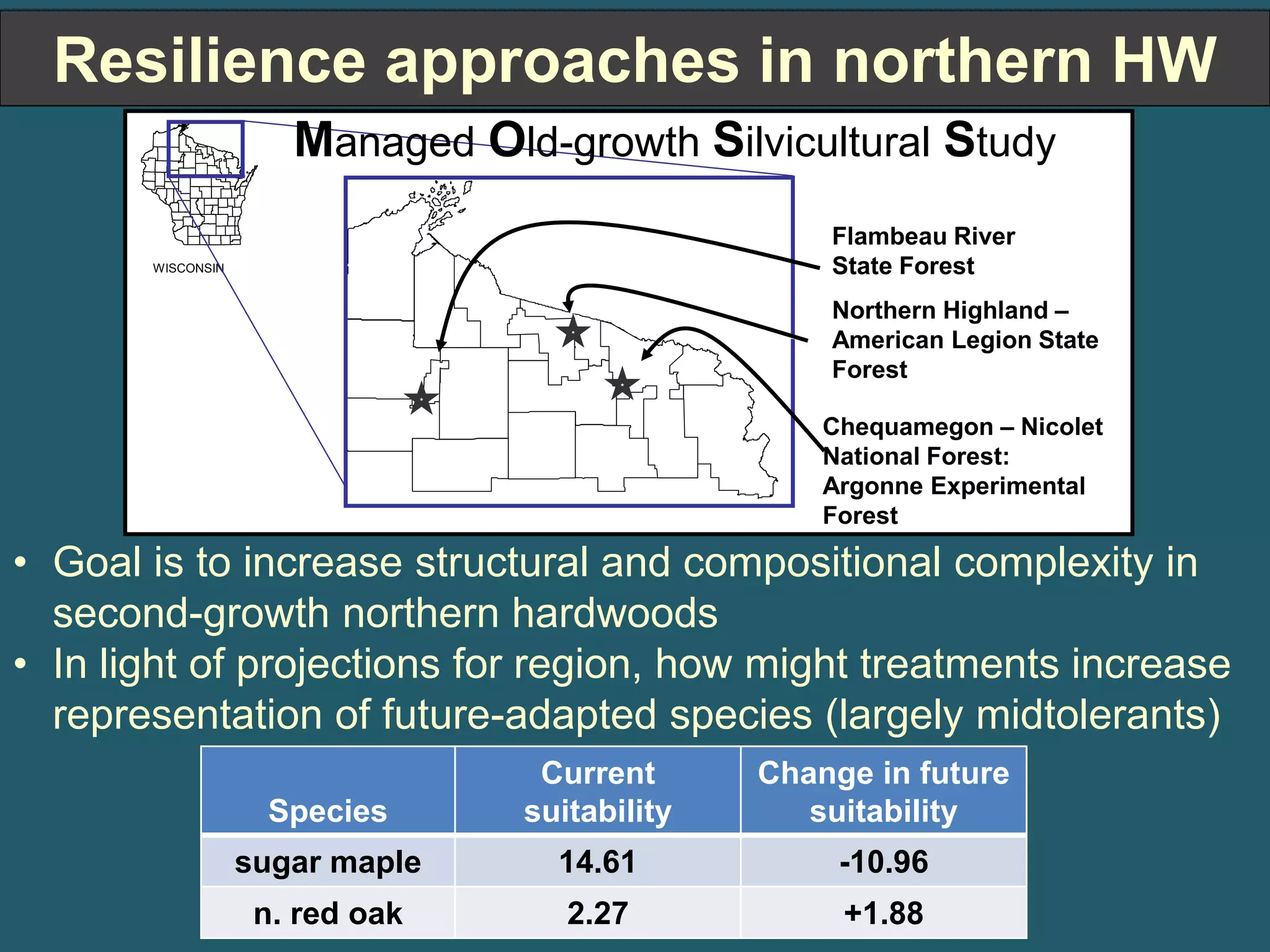

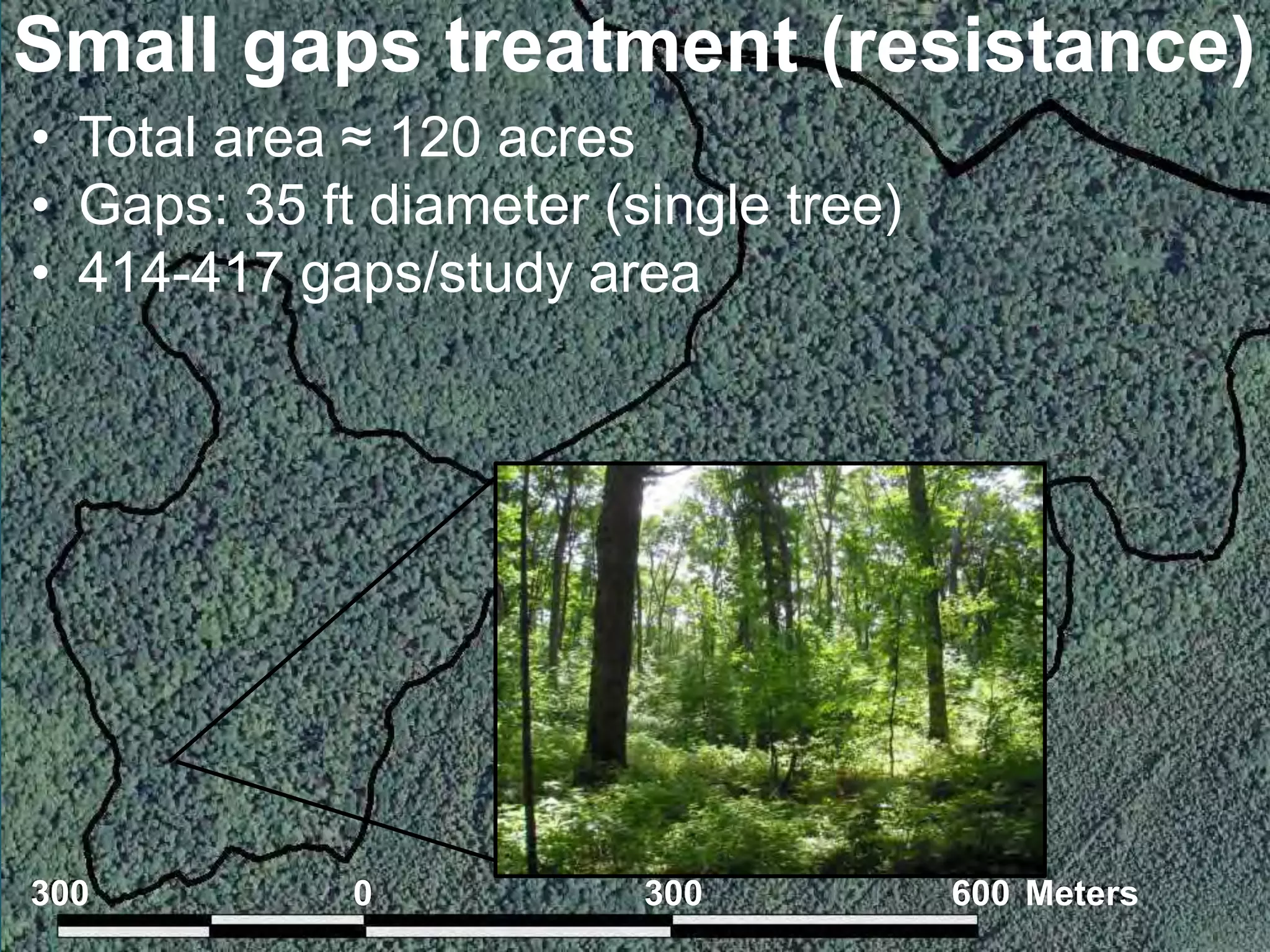

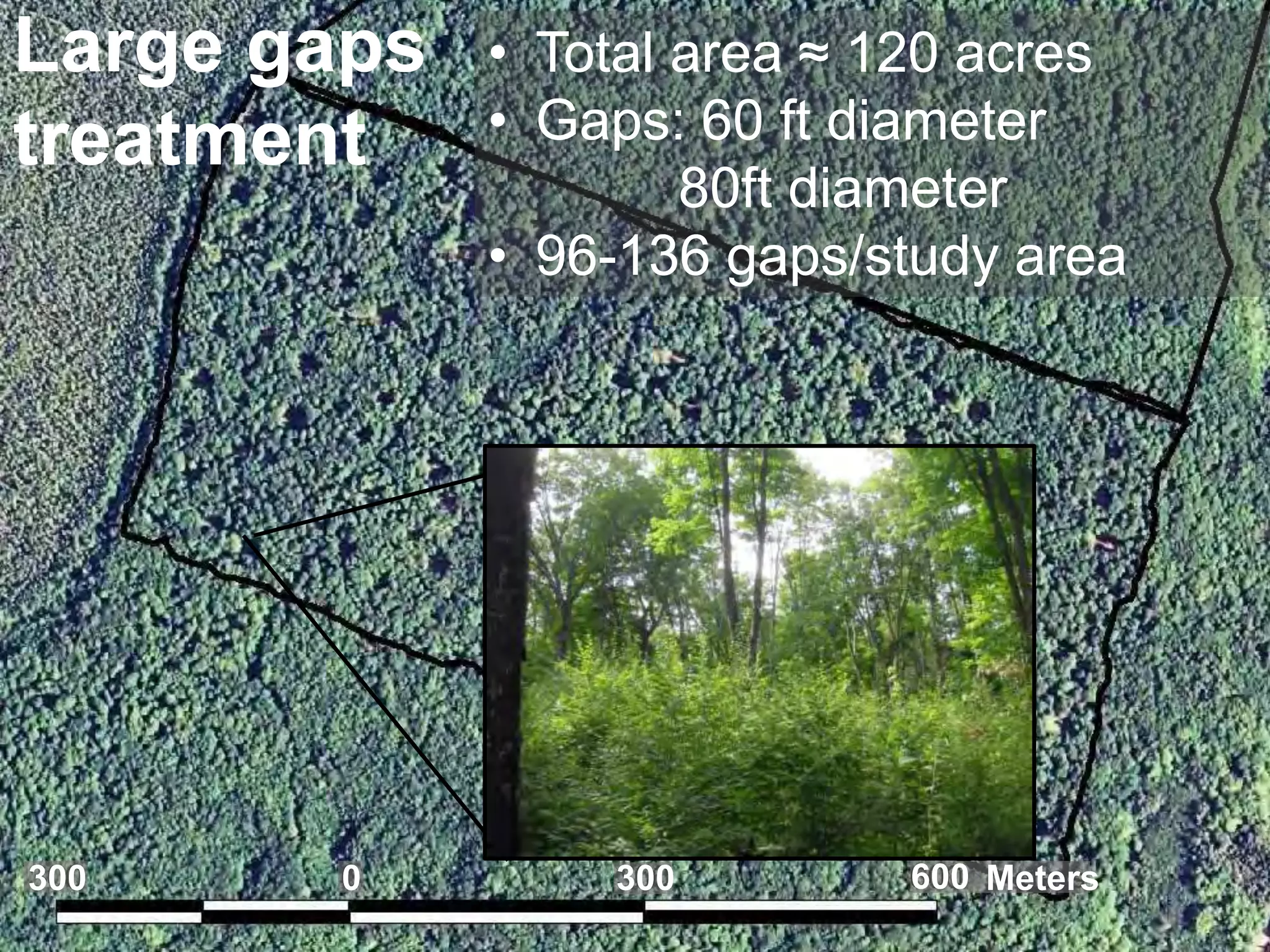

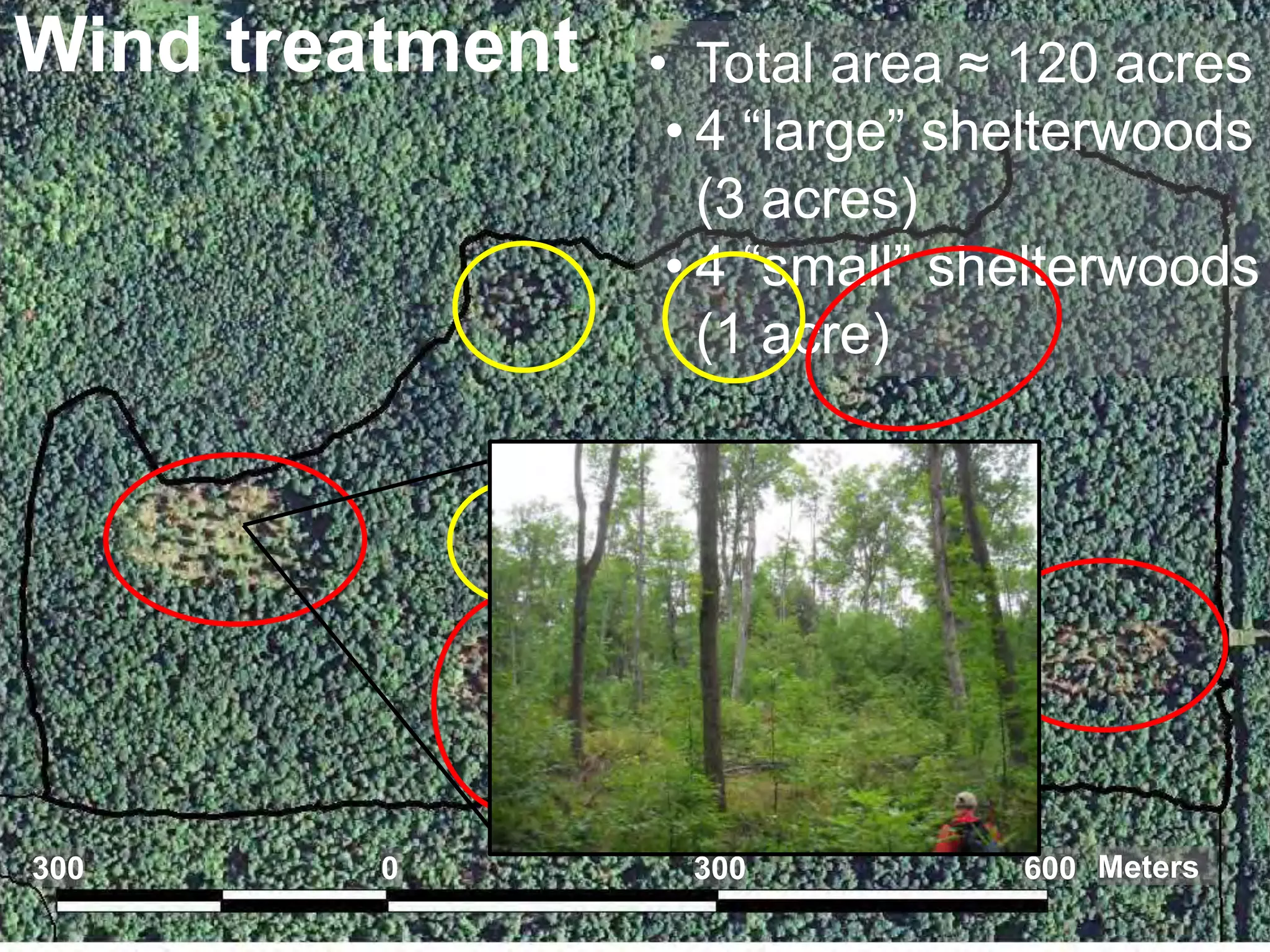

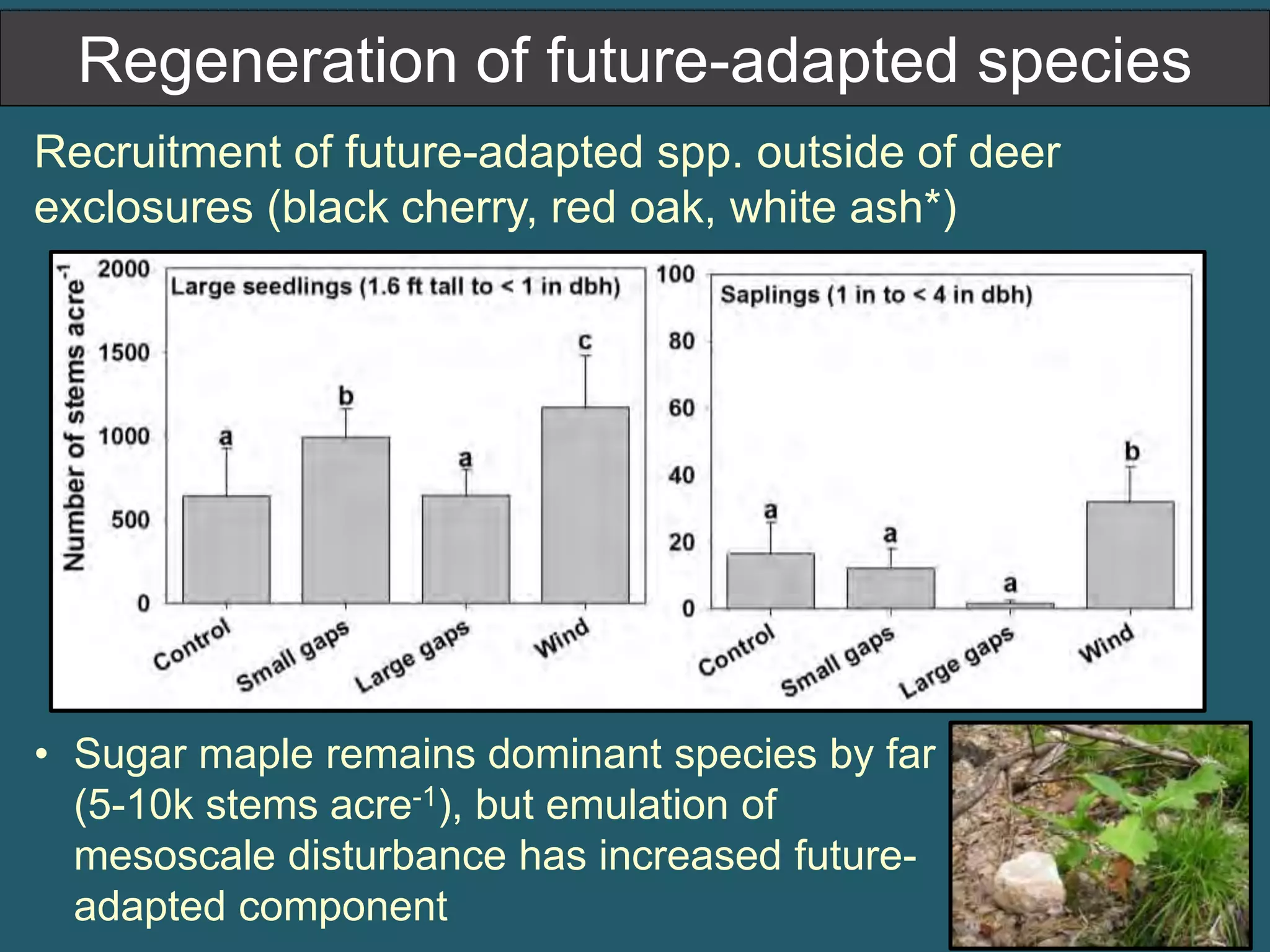

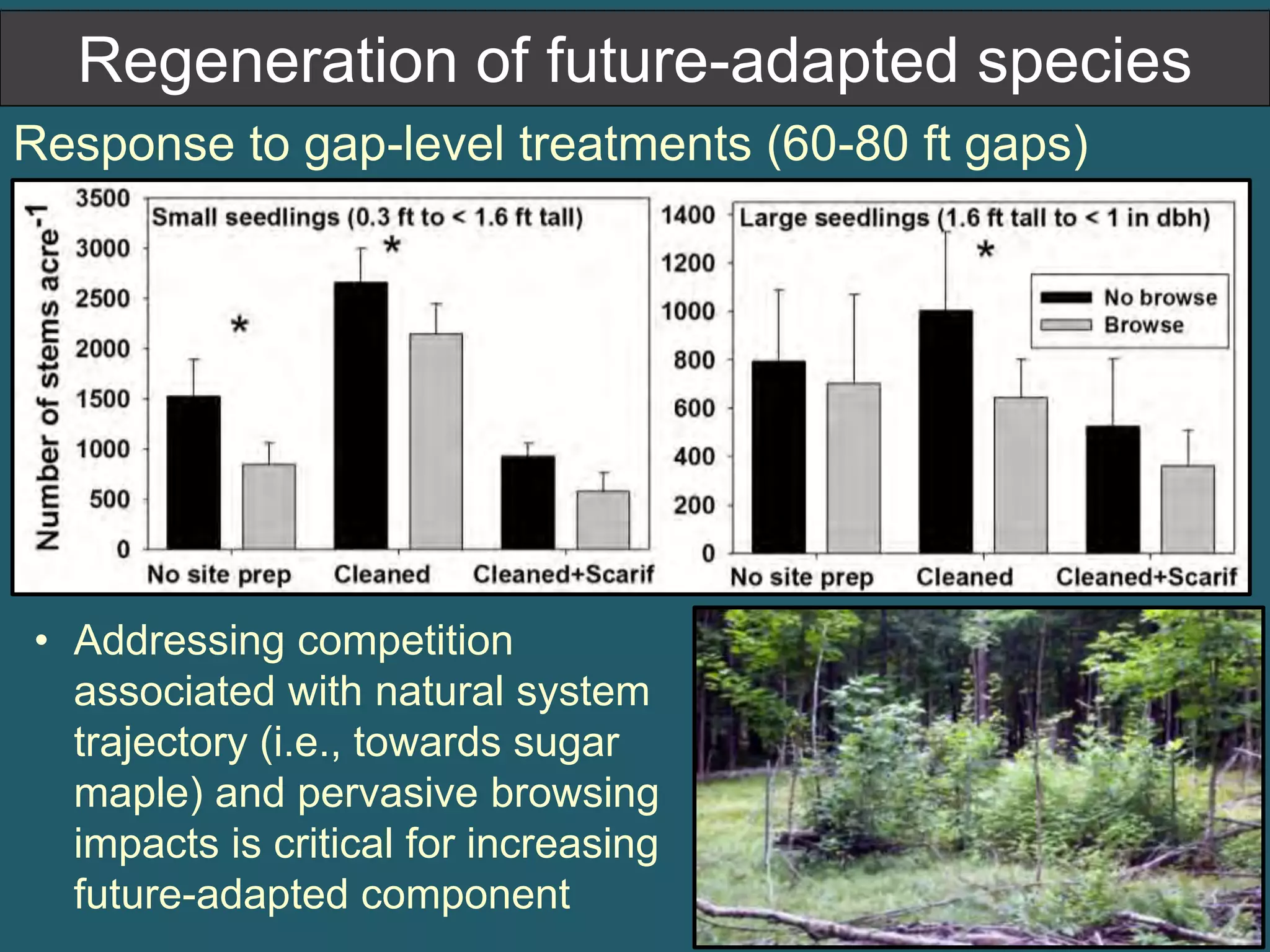

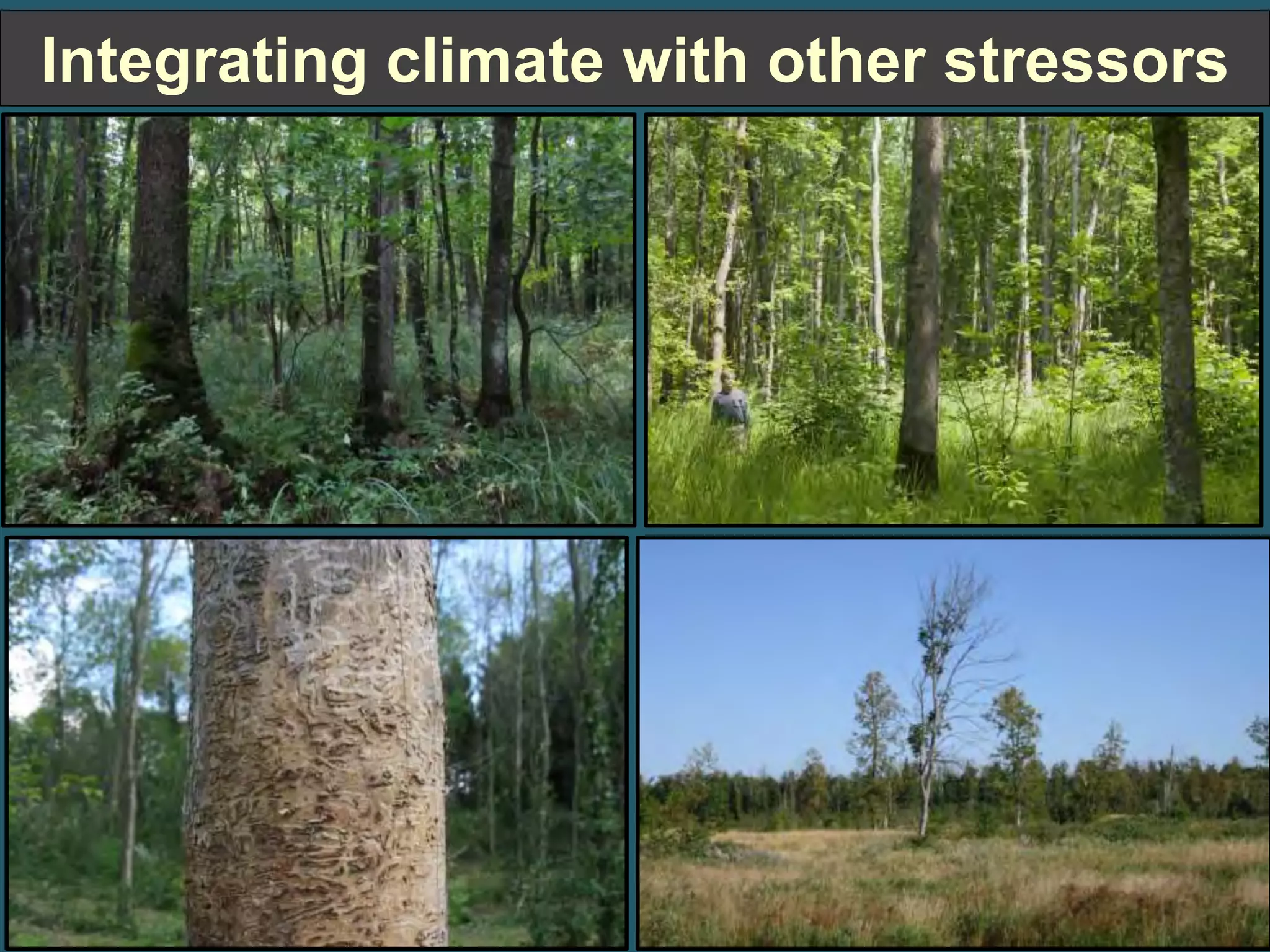

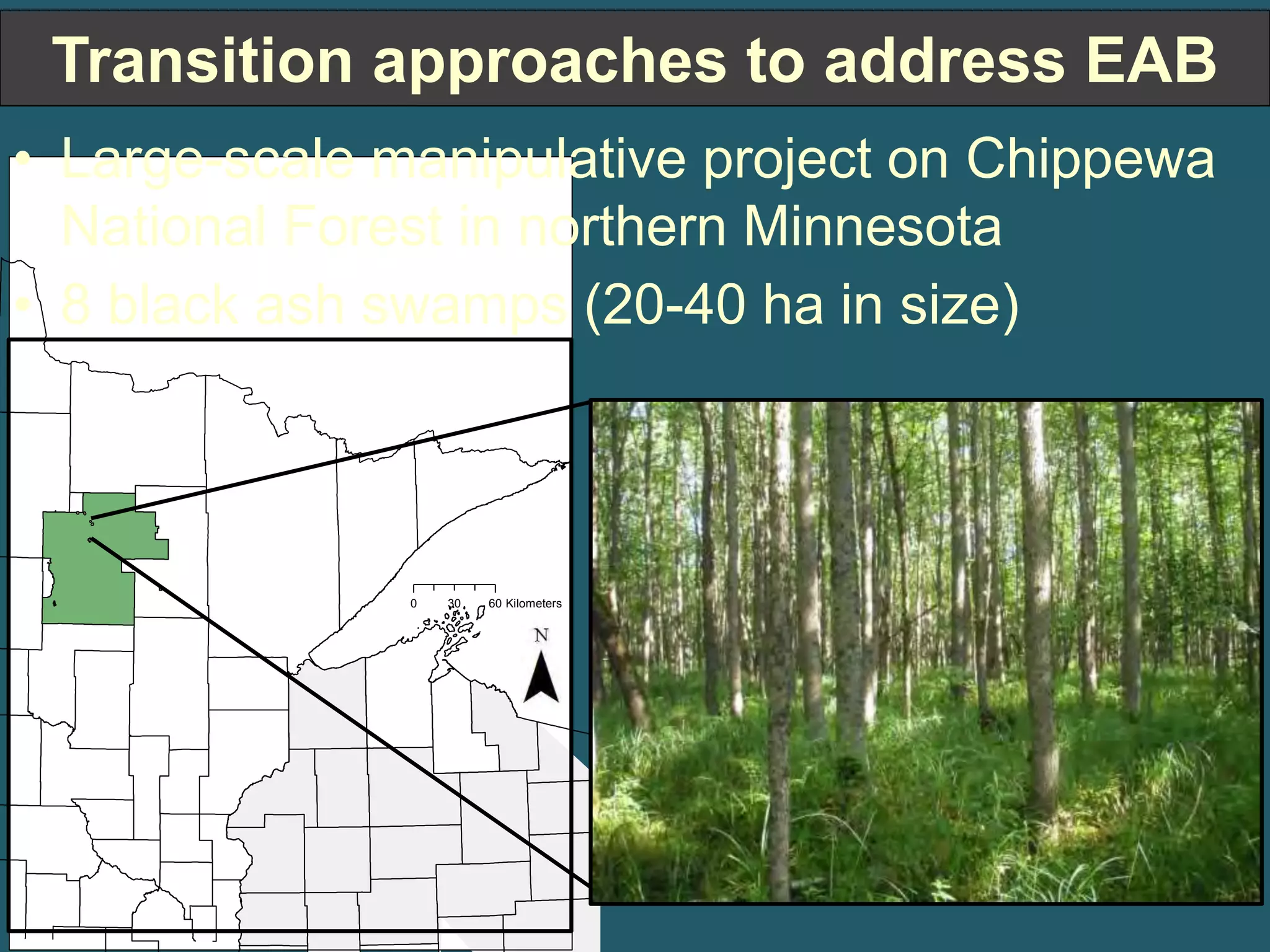

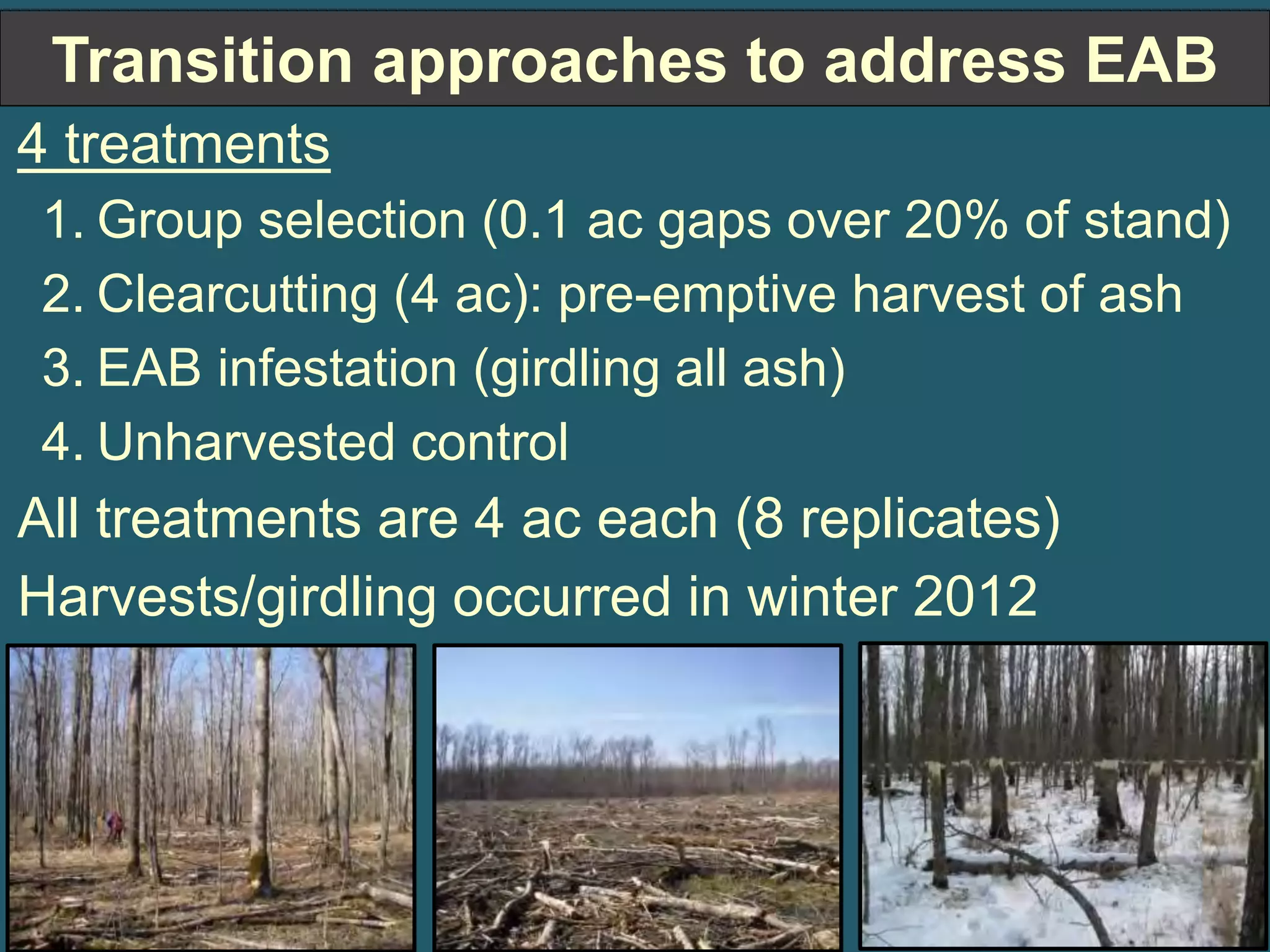

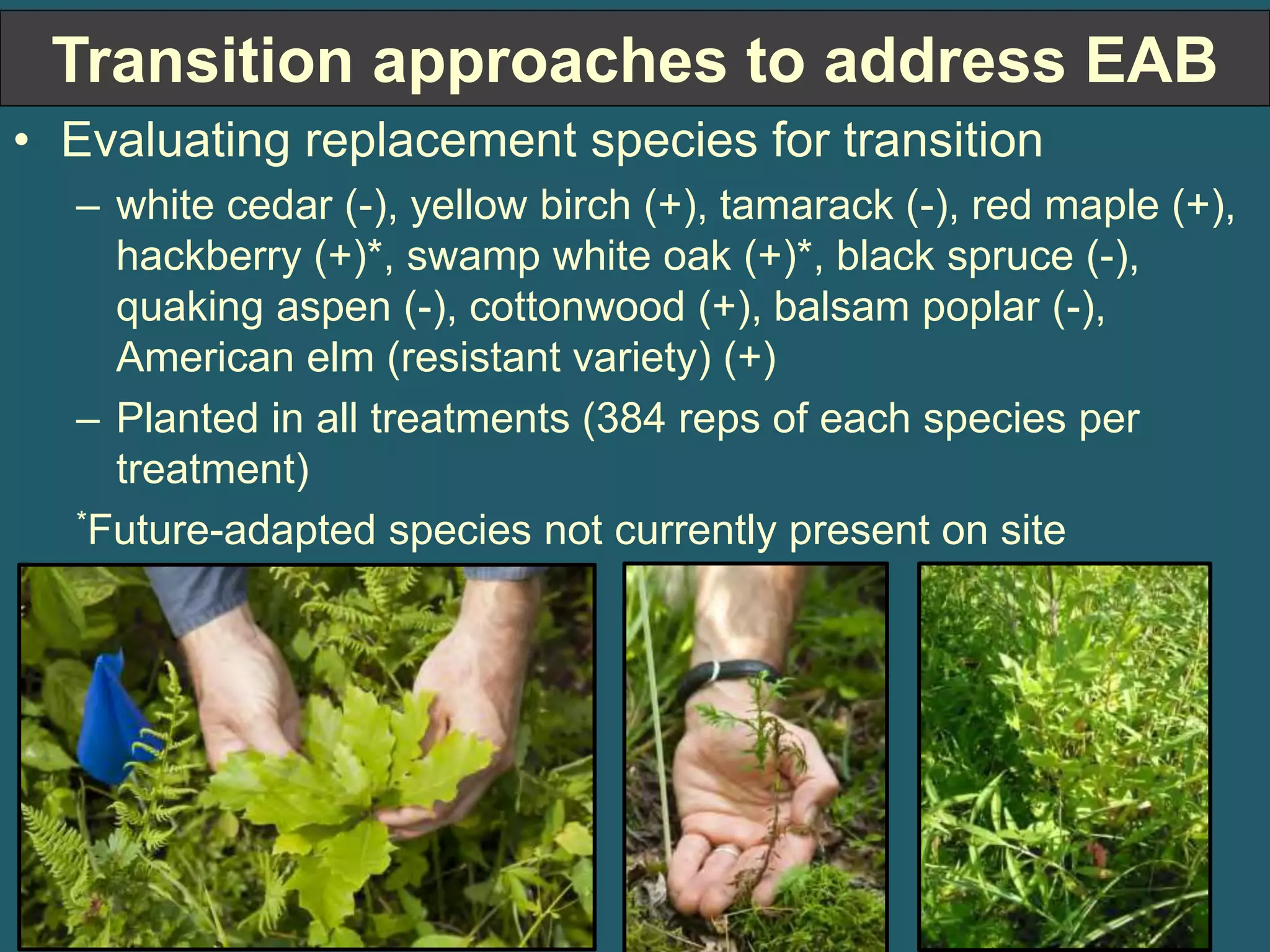

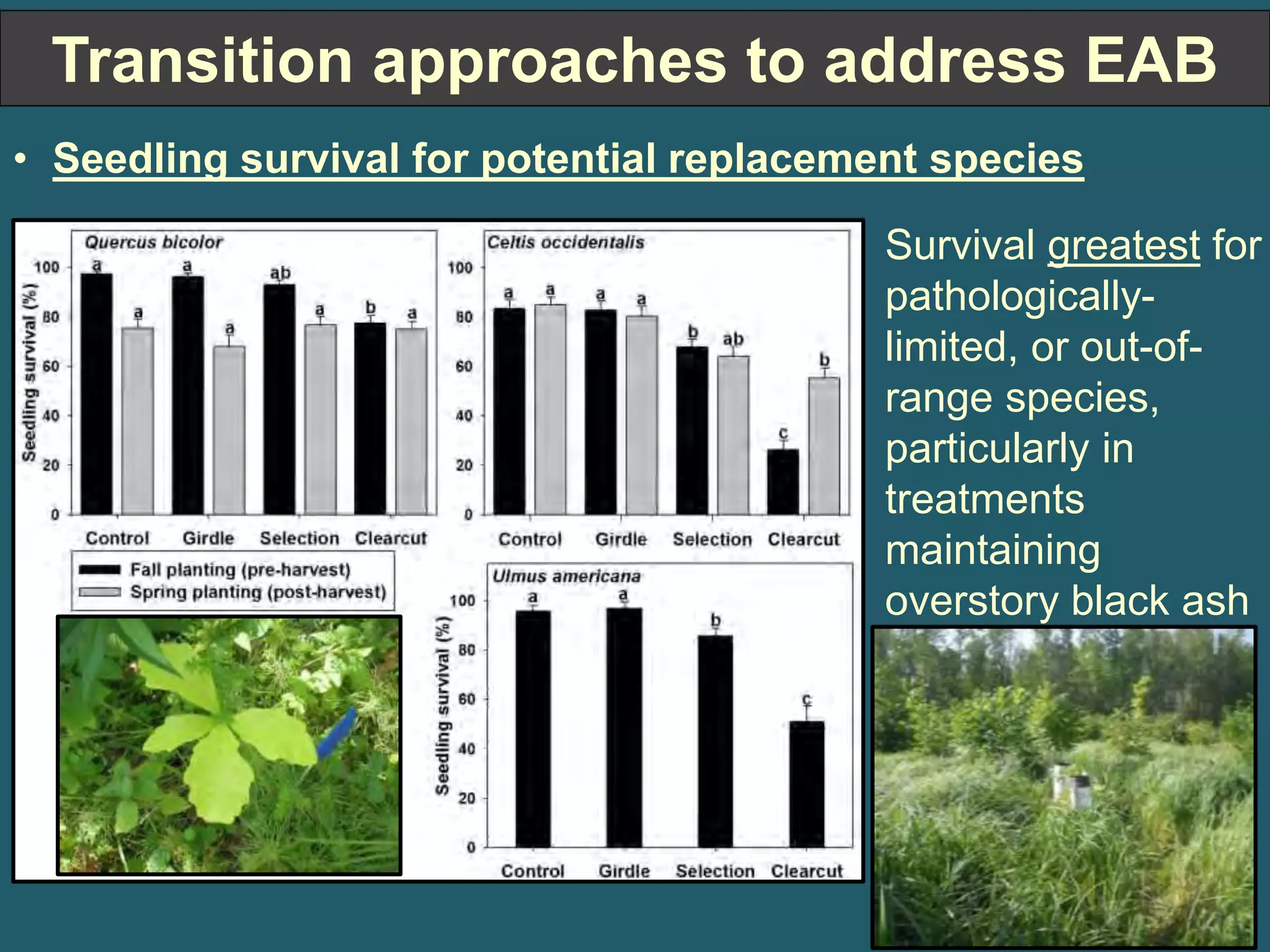

This document discusses approaches to forest adaptation in the context of climate change. It provides examples of forest management strategies along a continuum from resistance to change to transition and resilience. Resistance strategies aim to maintain current forest conditions through actions like thinning to reduce drought impacts. Transition and resilience strategies facilitate adaptive responses by increasing representation of future-adapted species, such as using regeneration methods that allow recruitment of species like northern red oak during overstory retention. The examples shown indicate that restoring structural complexity and processes like large gaps can help recruitment without removing the existing overstory. Maintaining options and embracing uncertainty are key to advancing adaptive forest management.