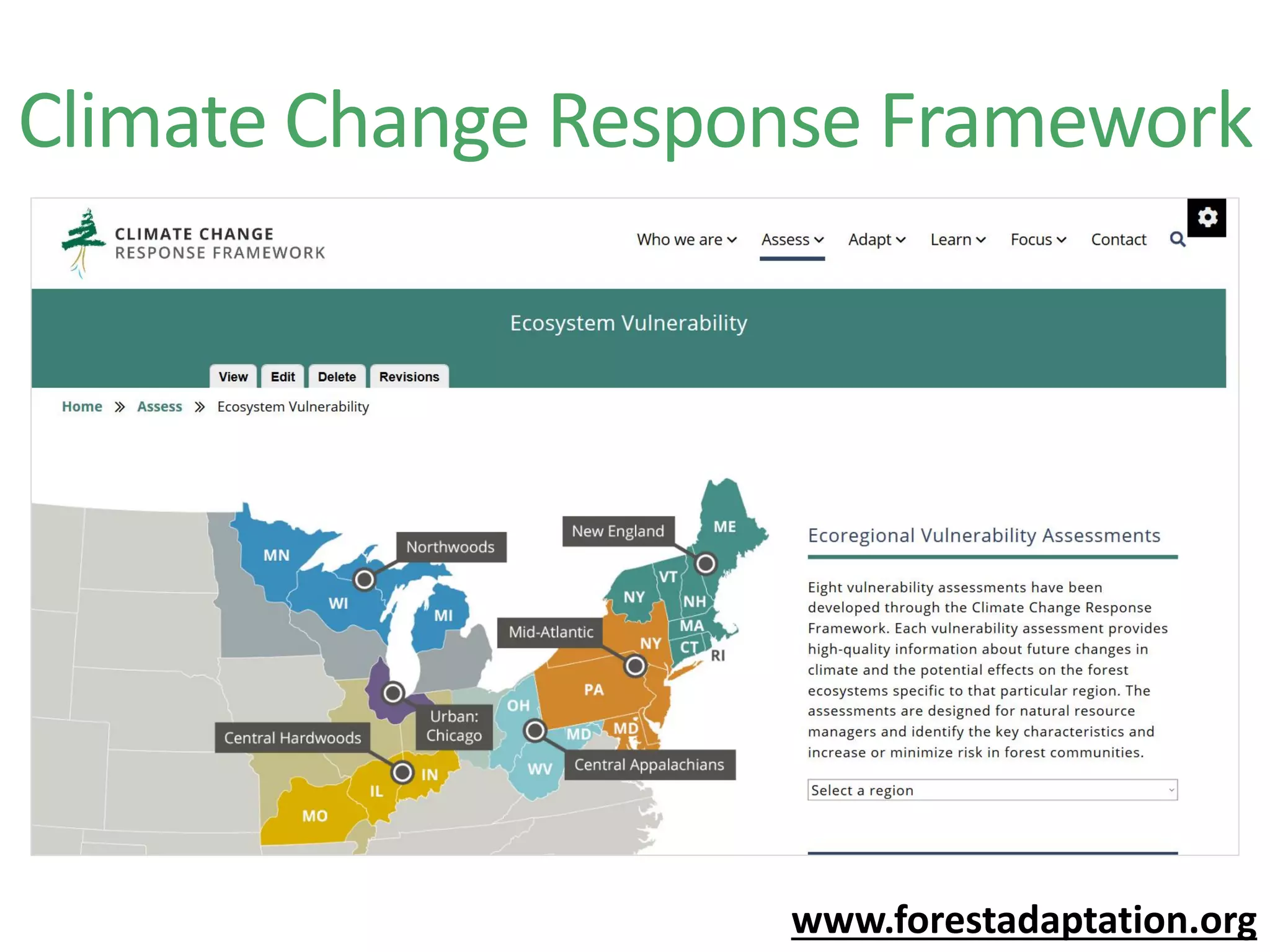

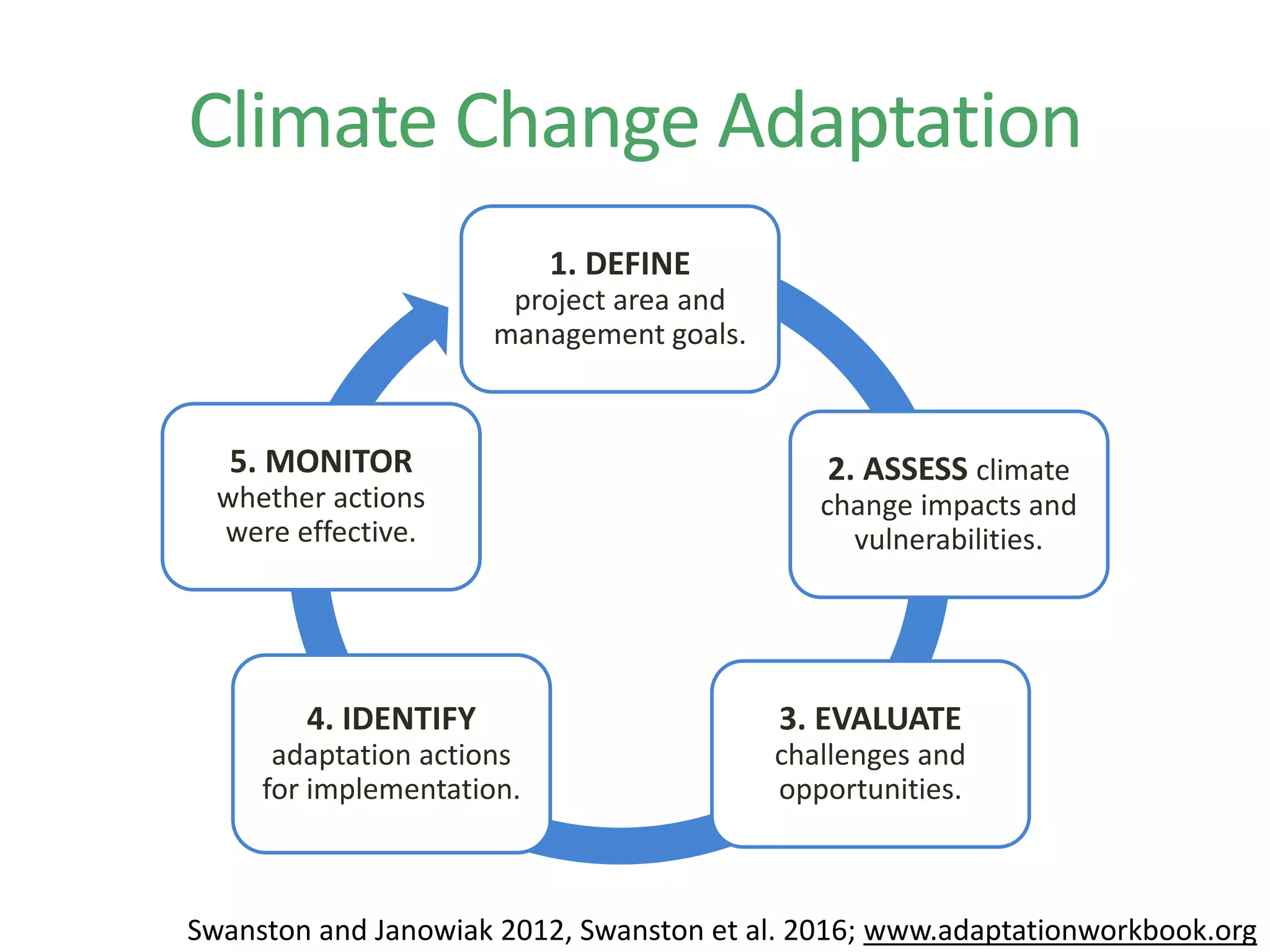

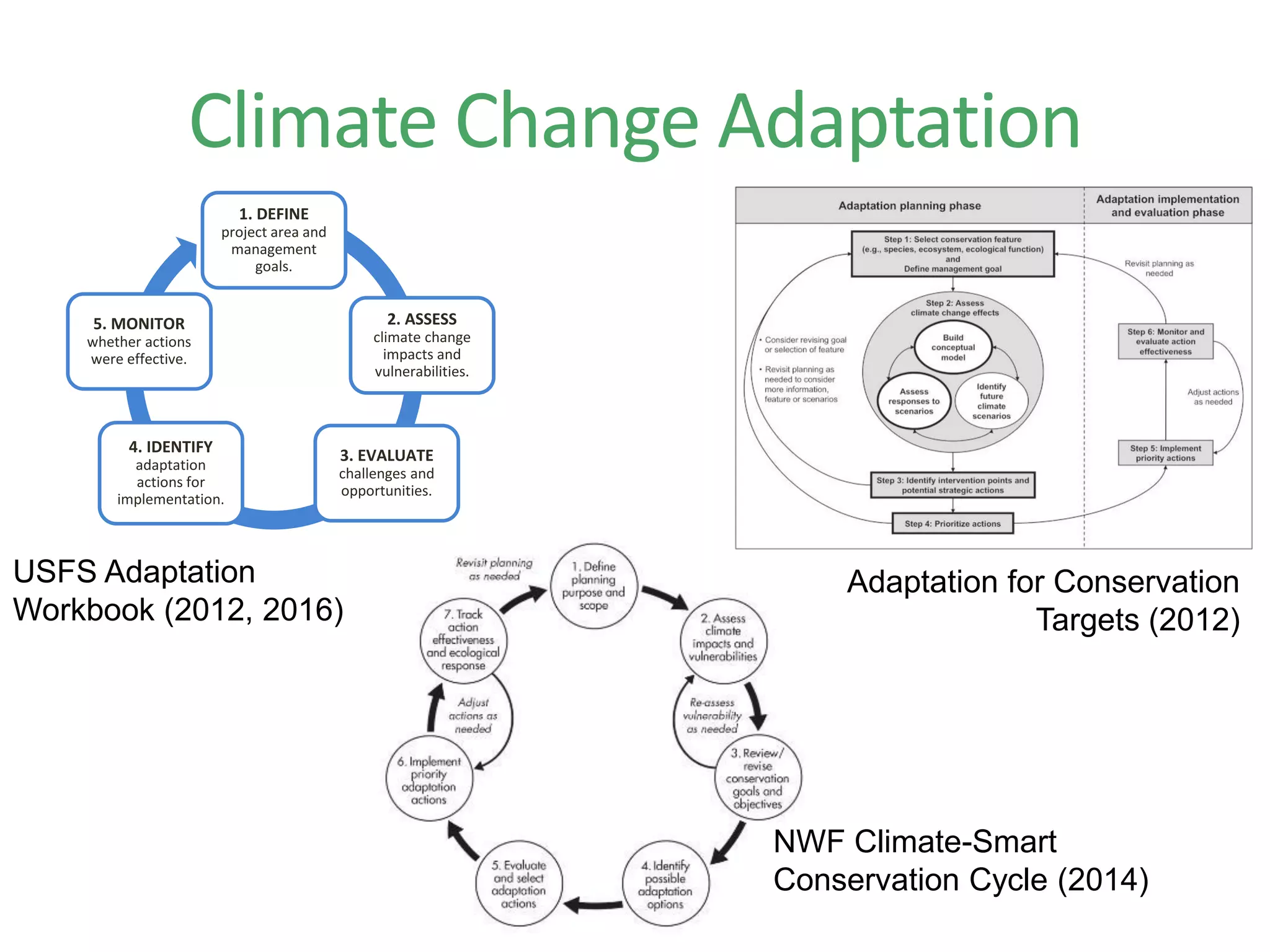

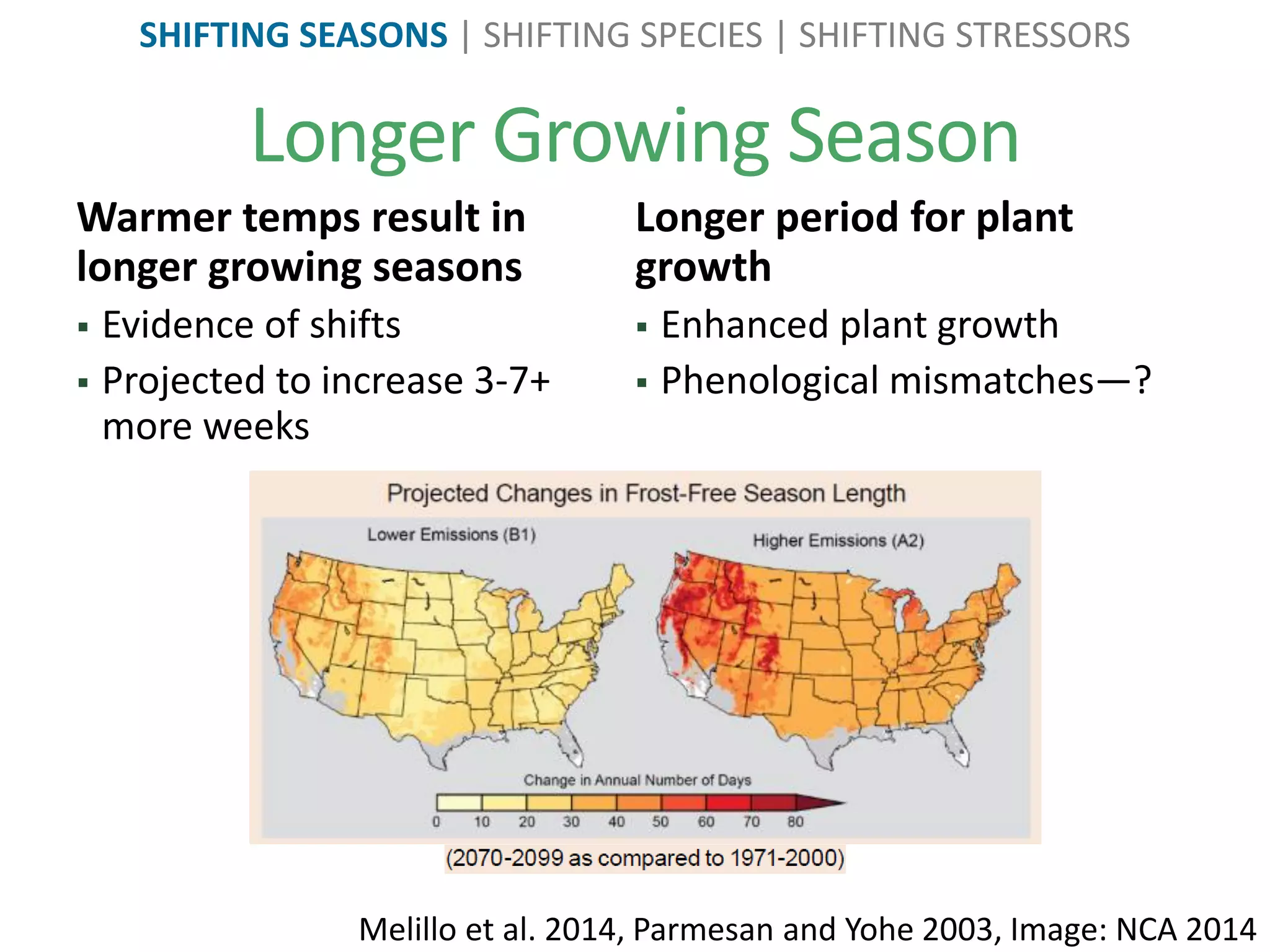

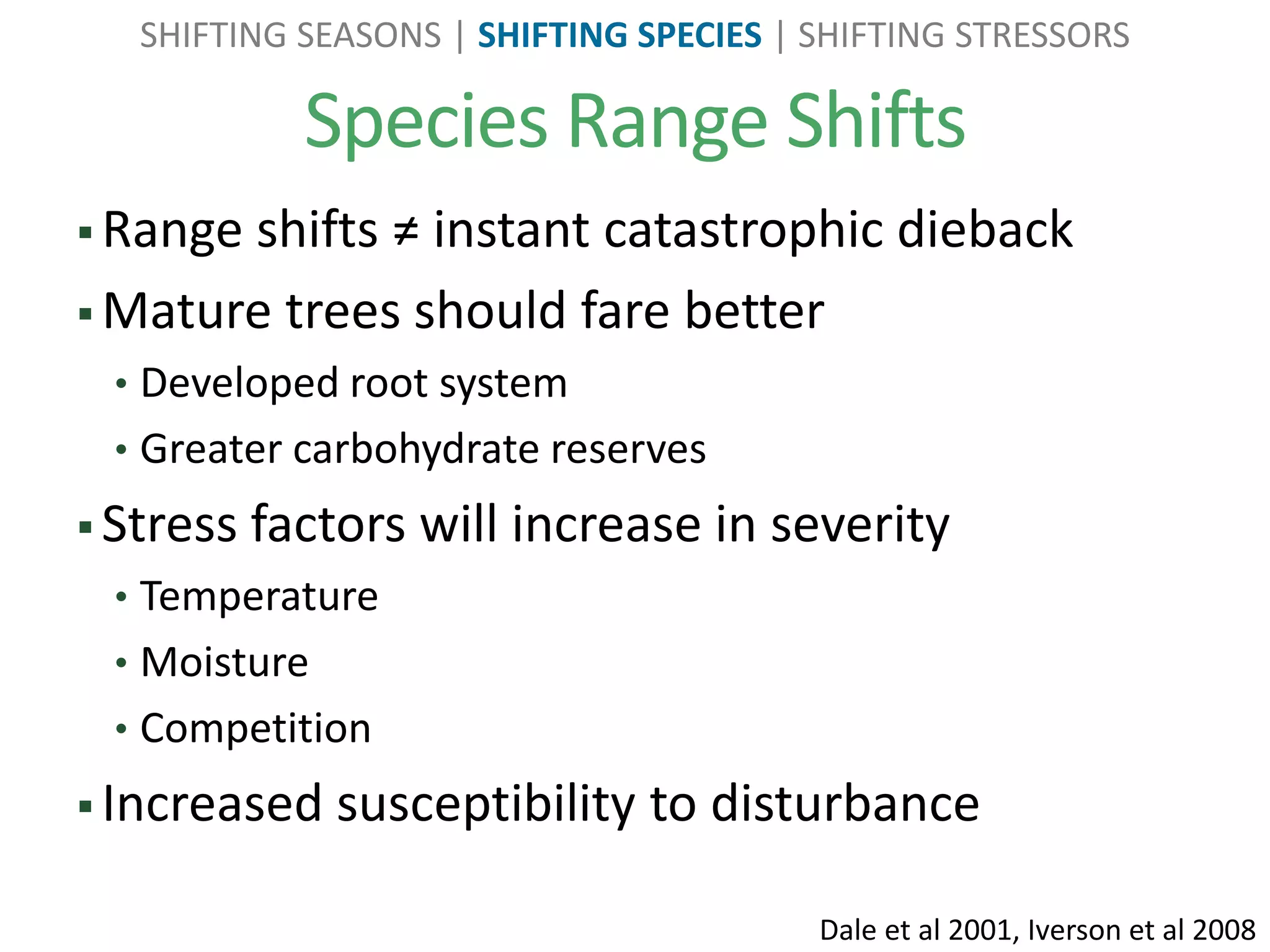

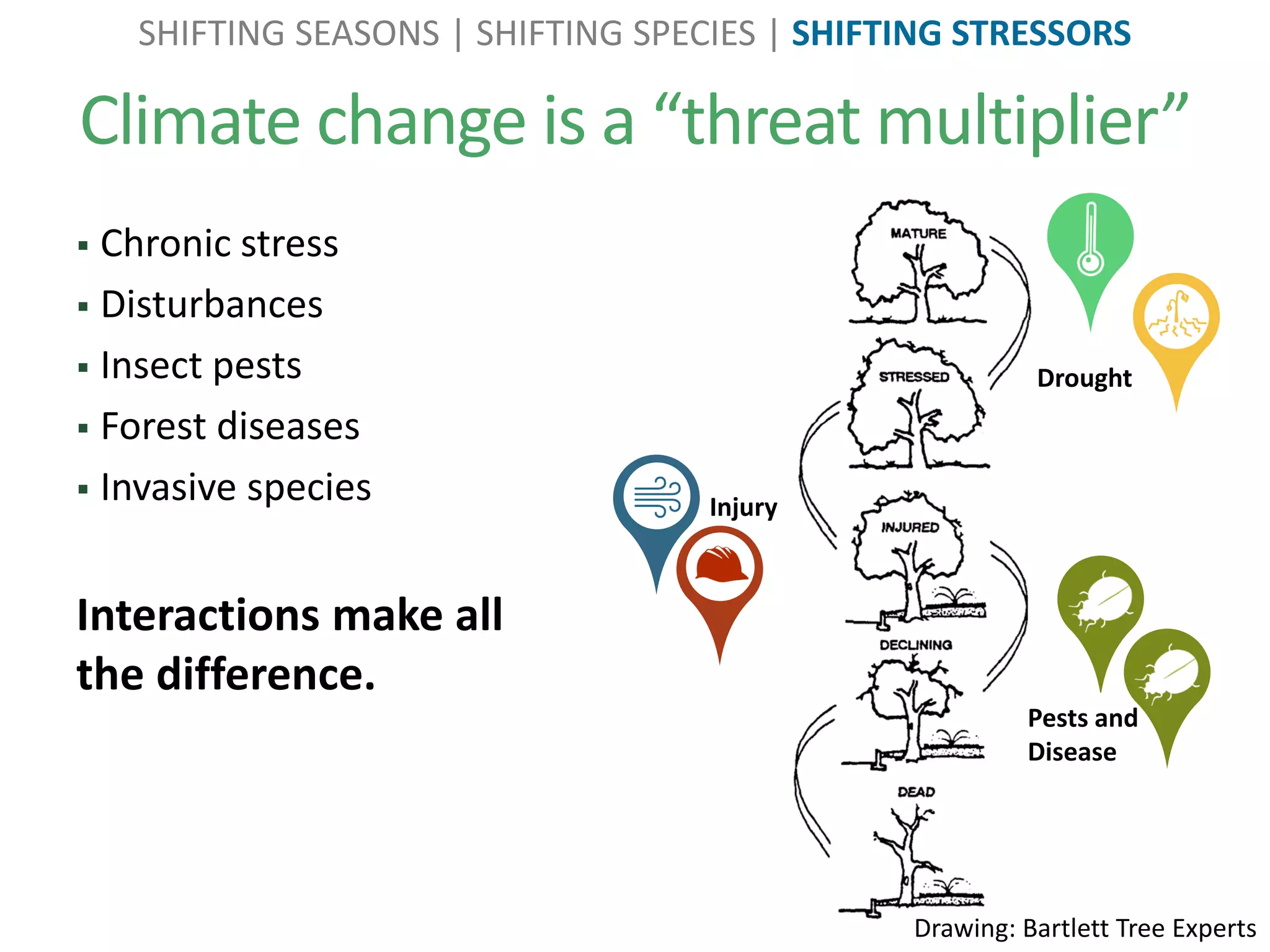

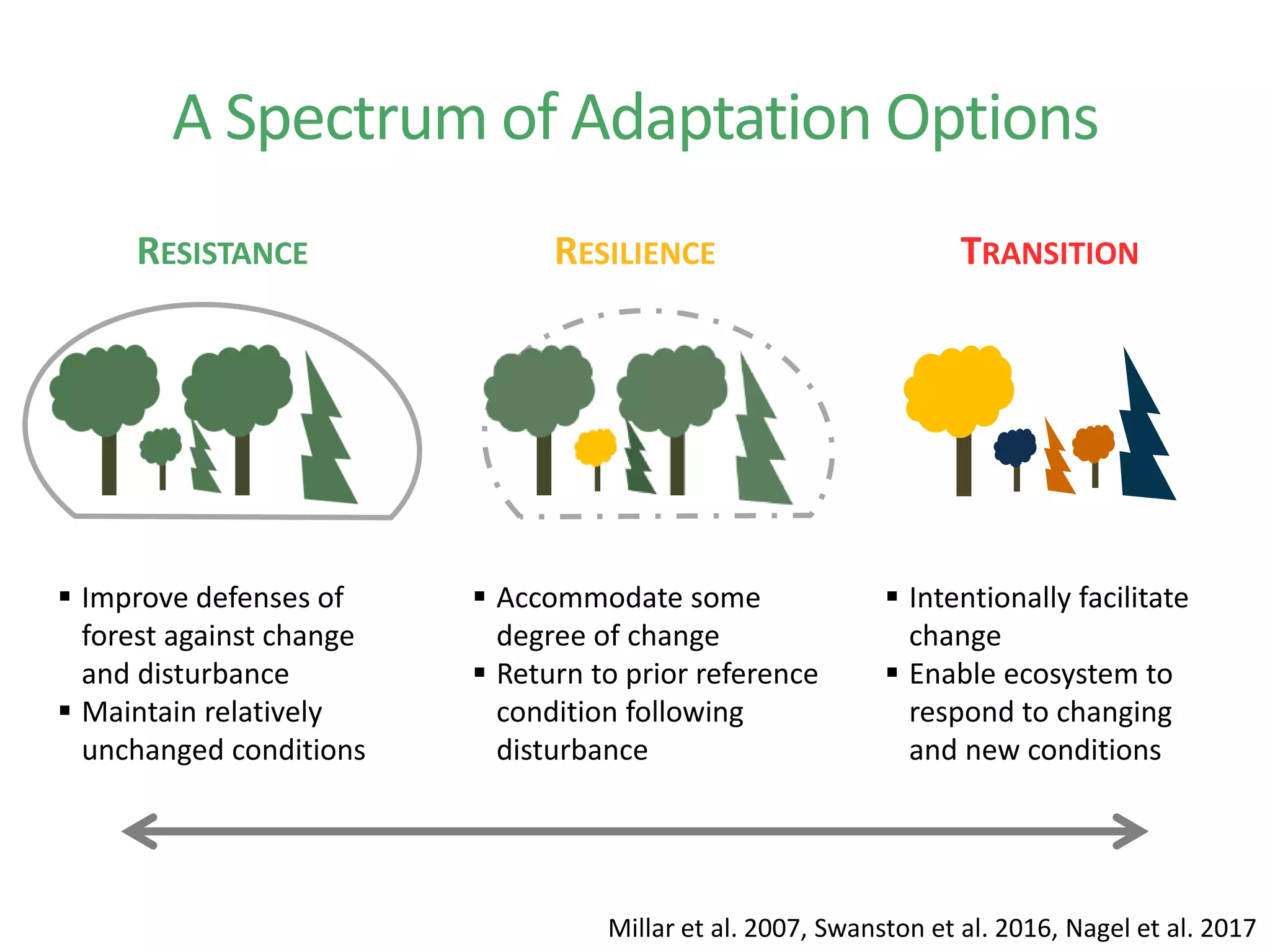

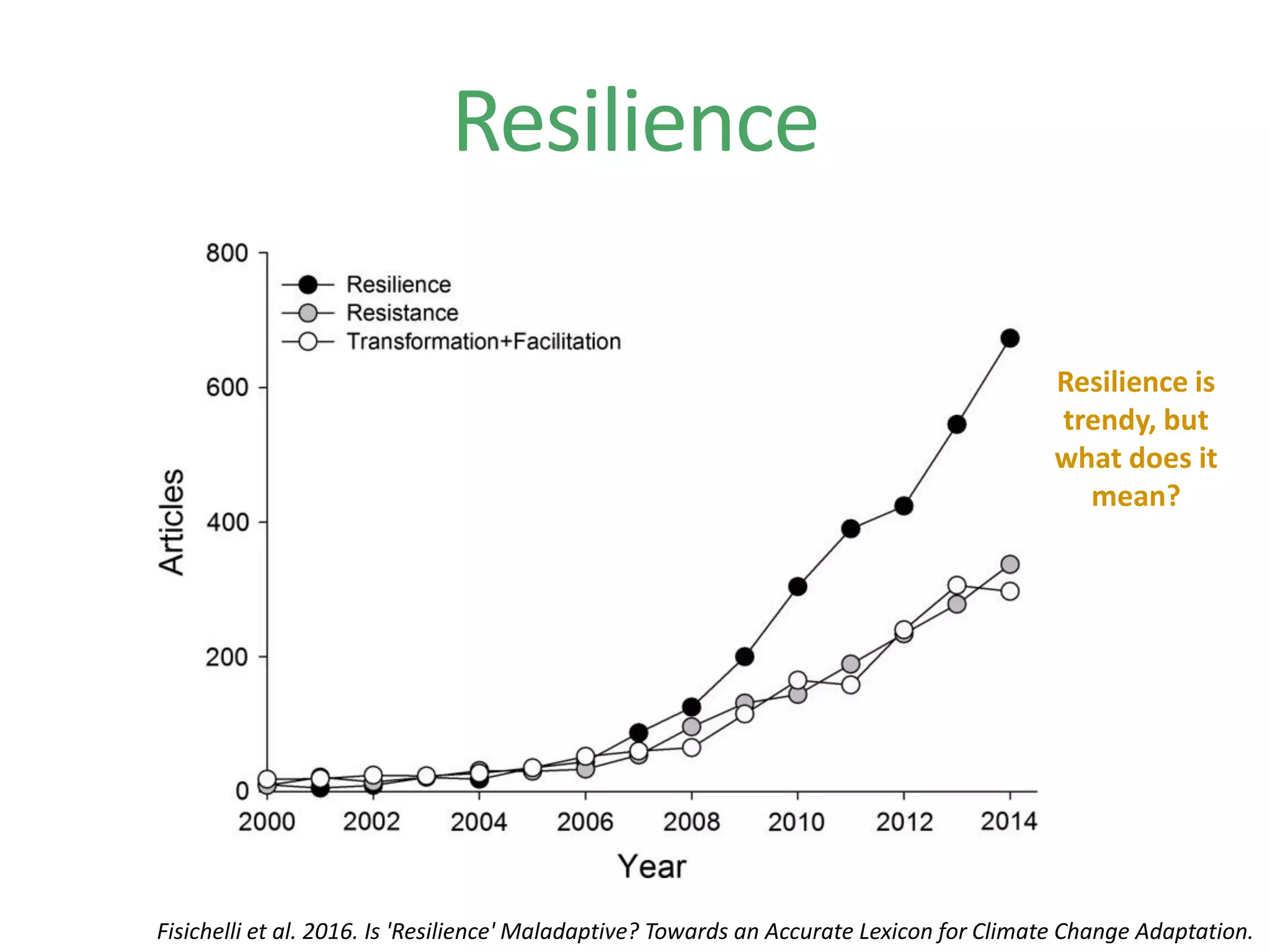

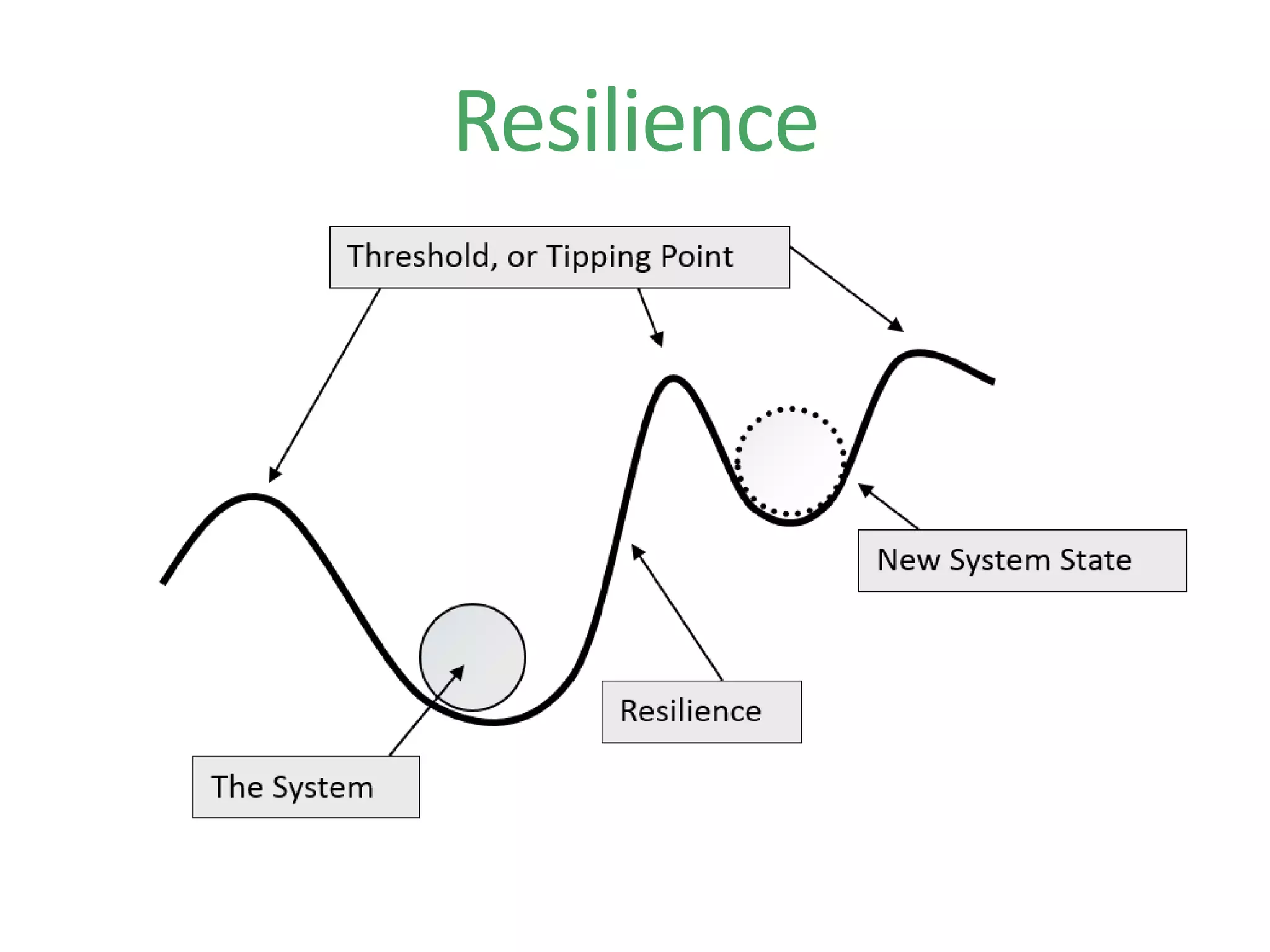

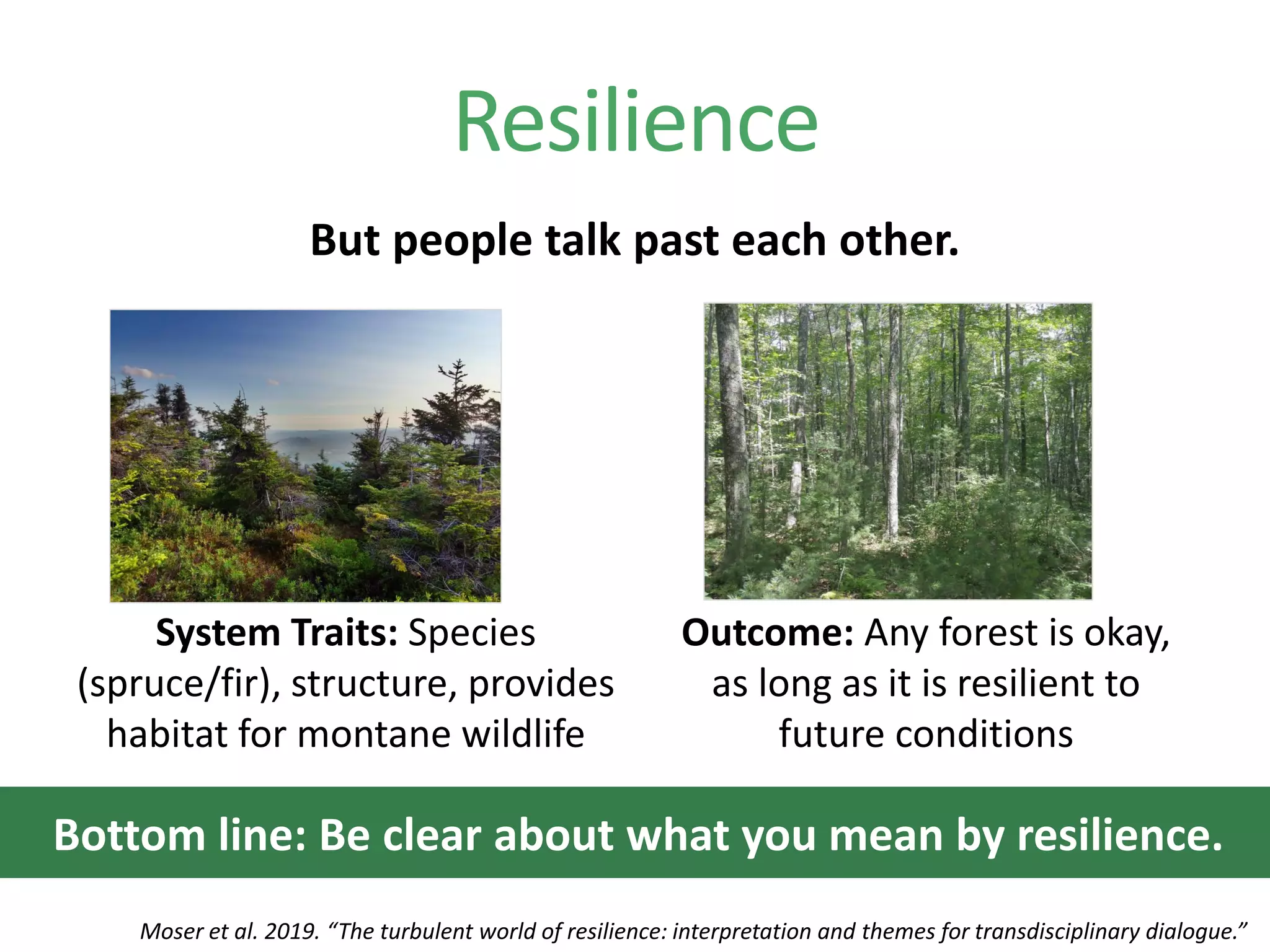

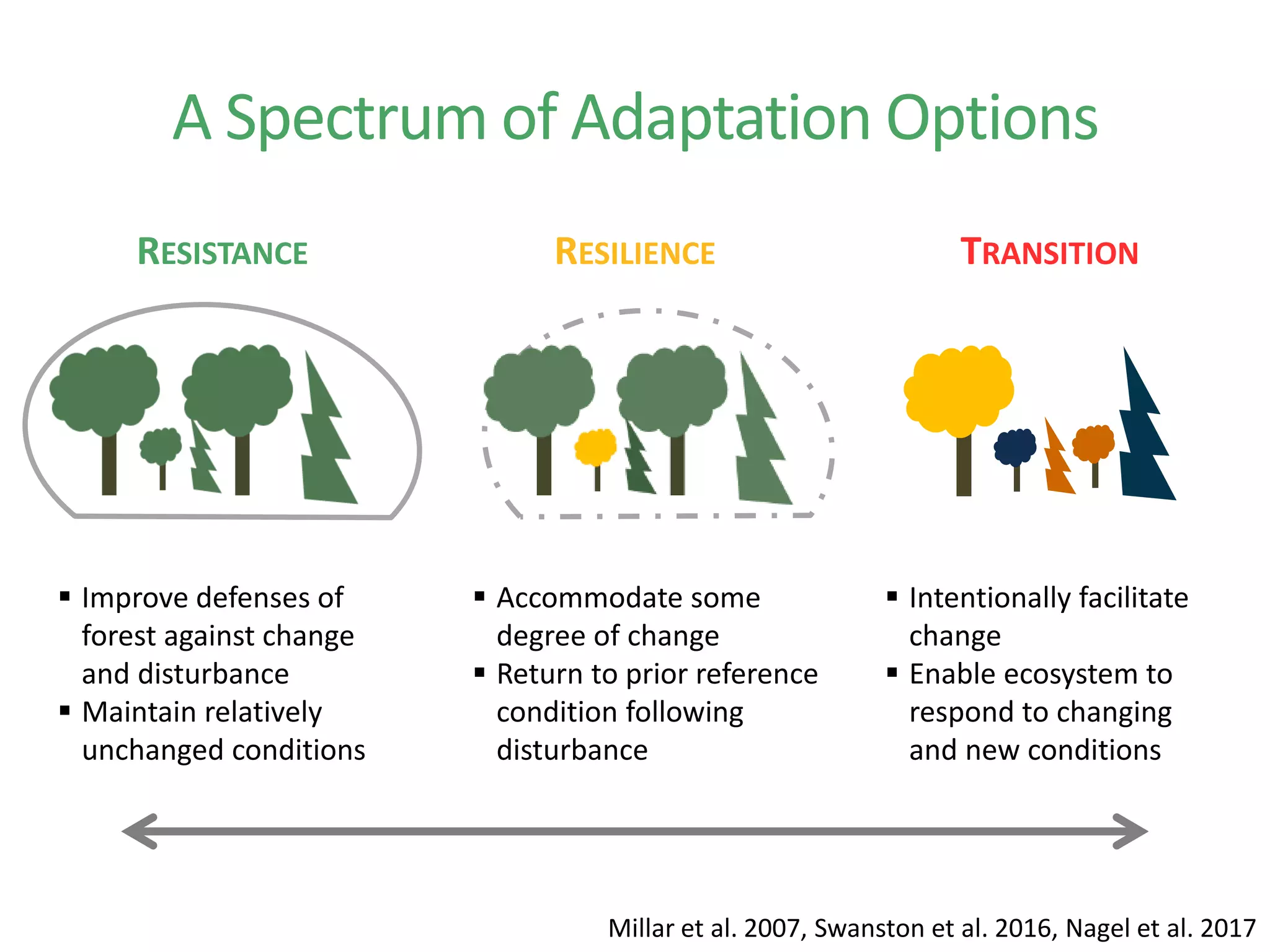

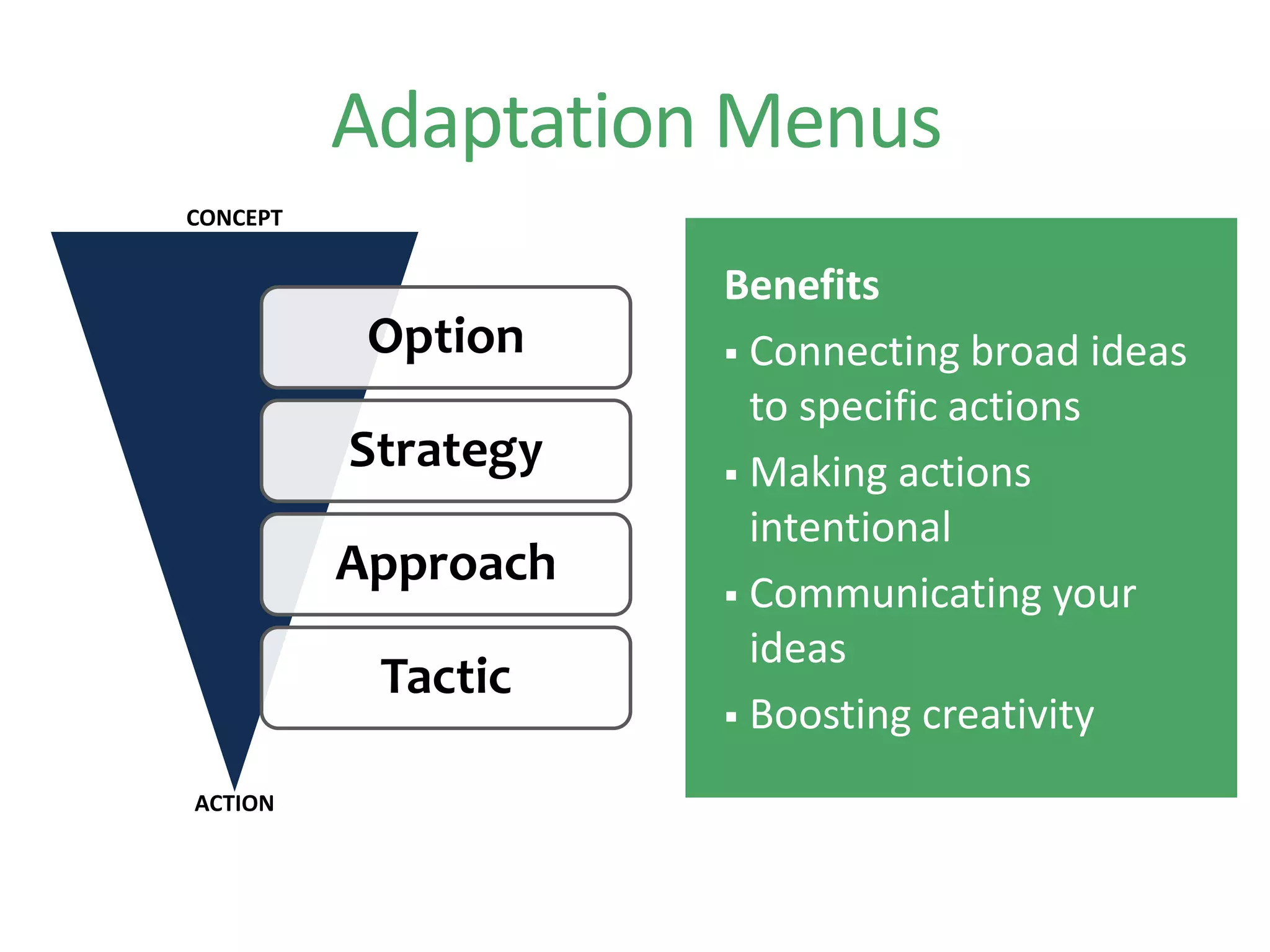

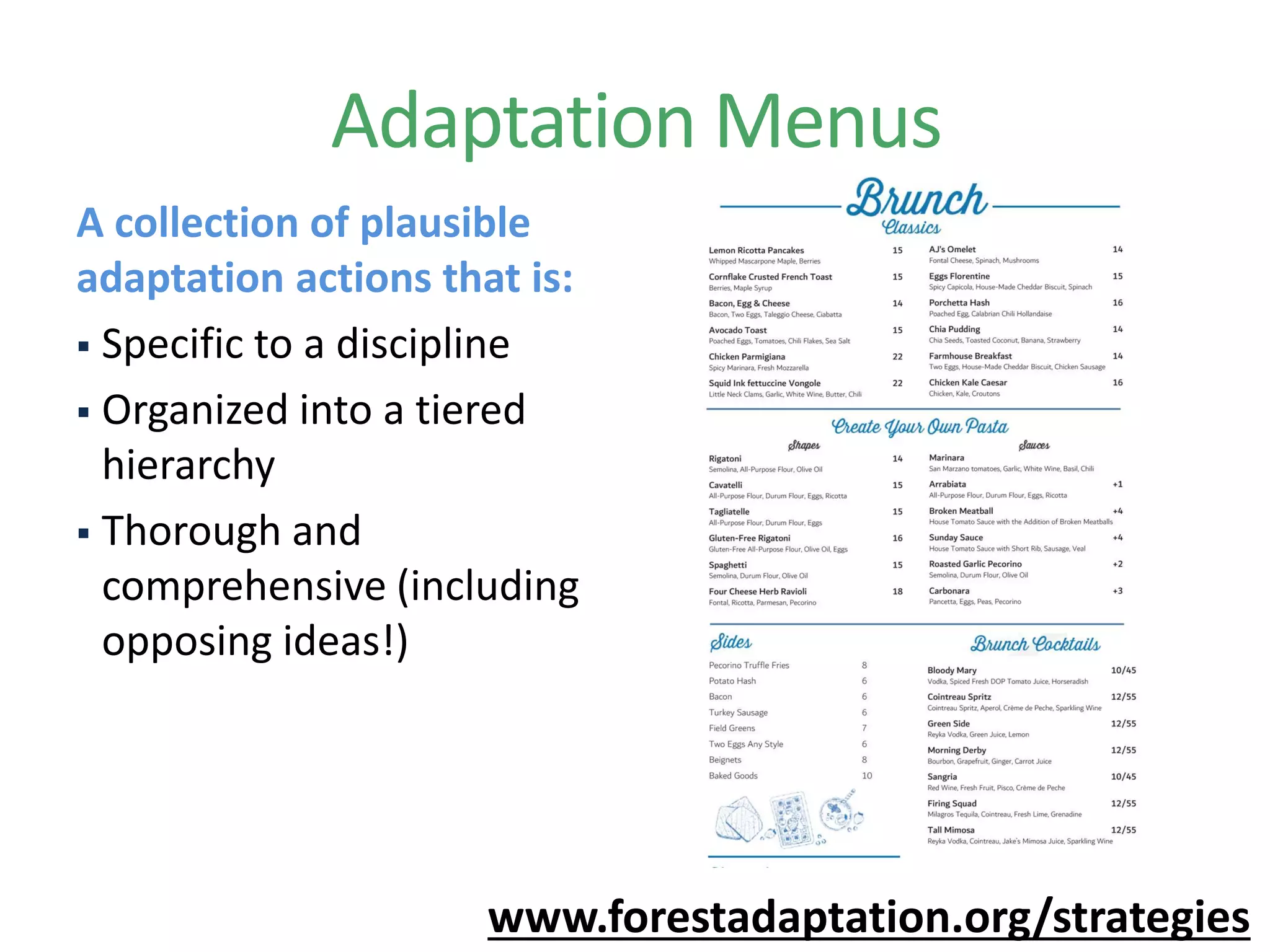

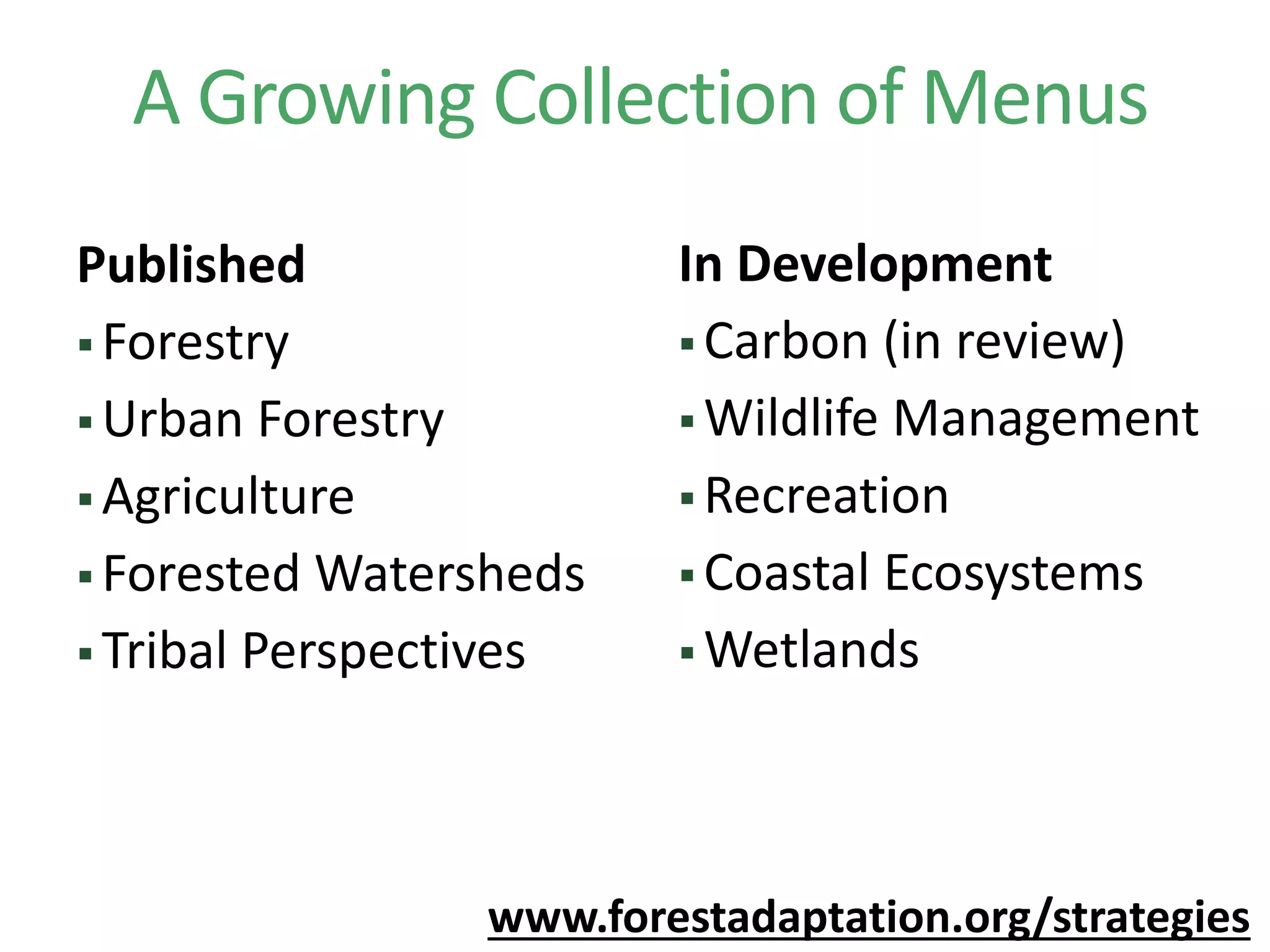

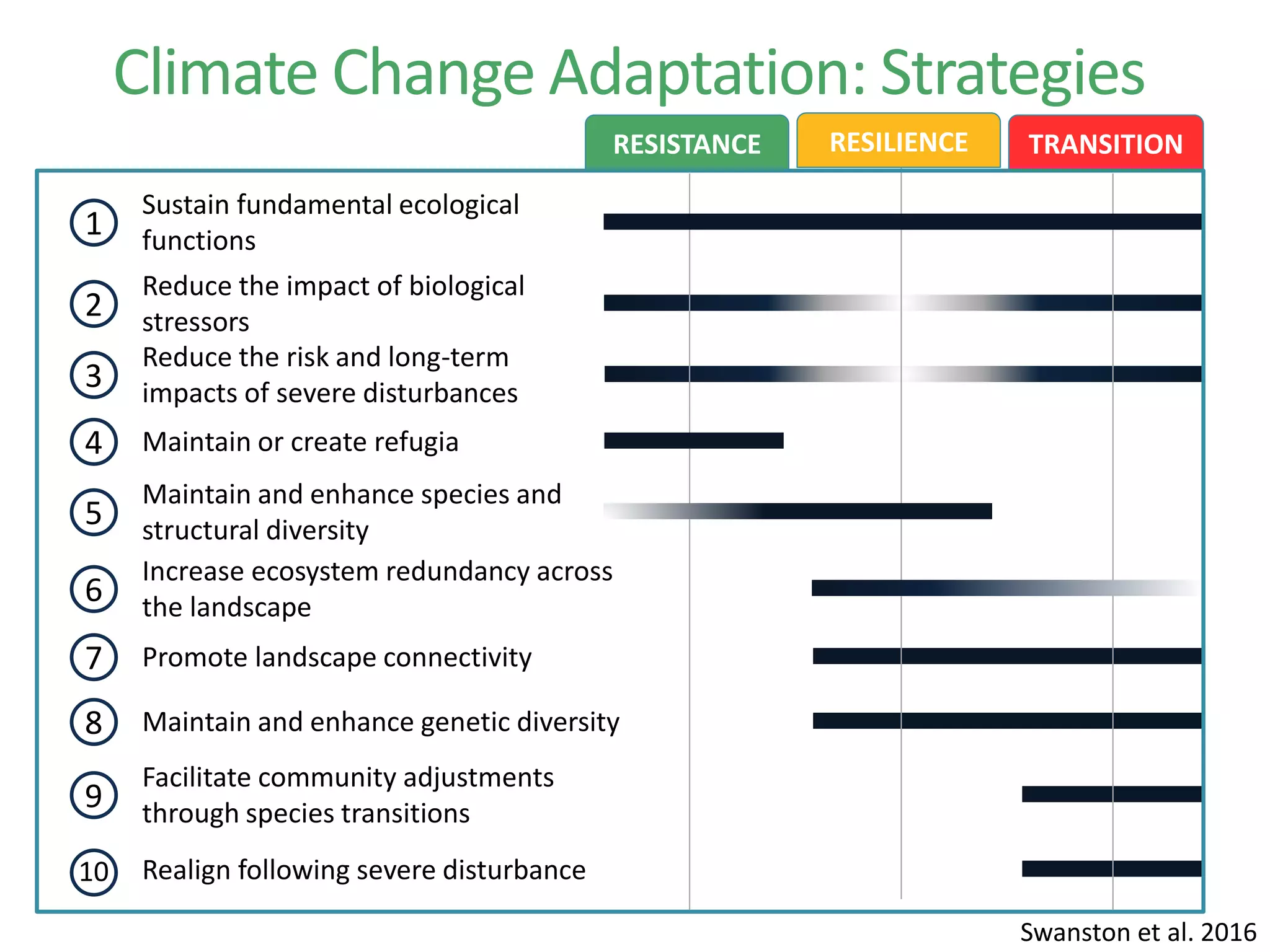

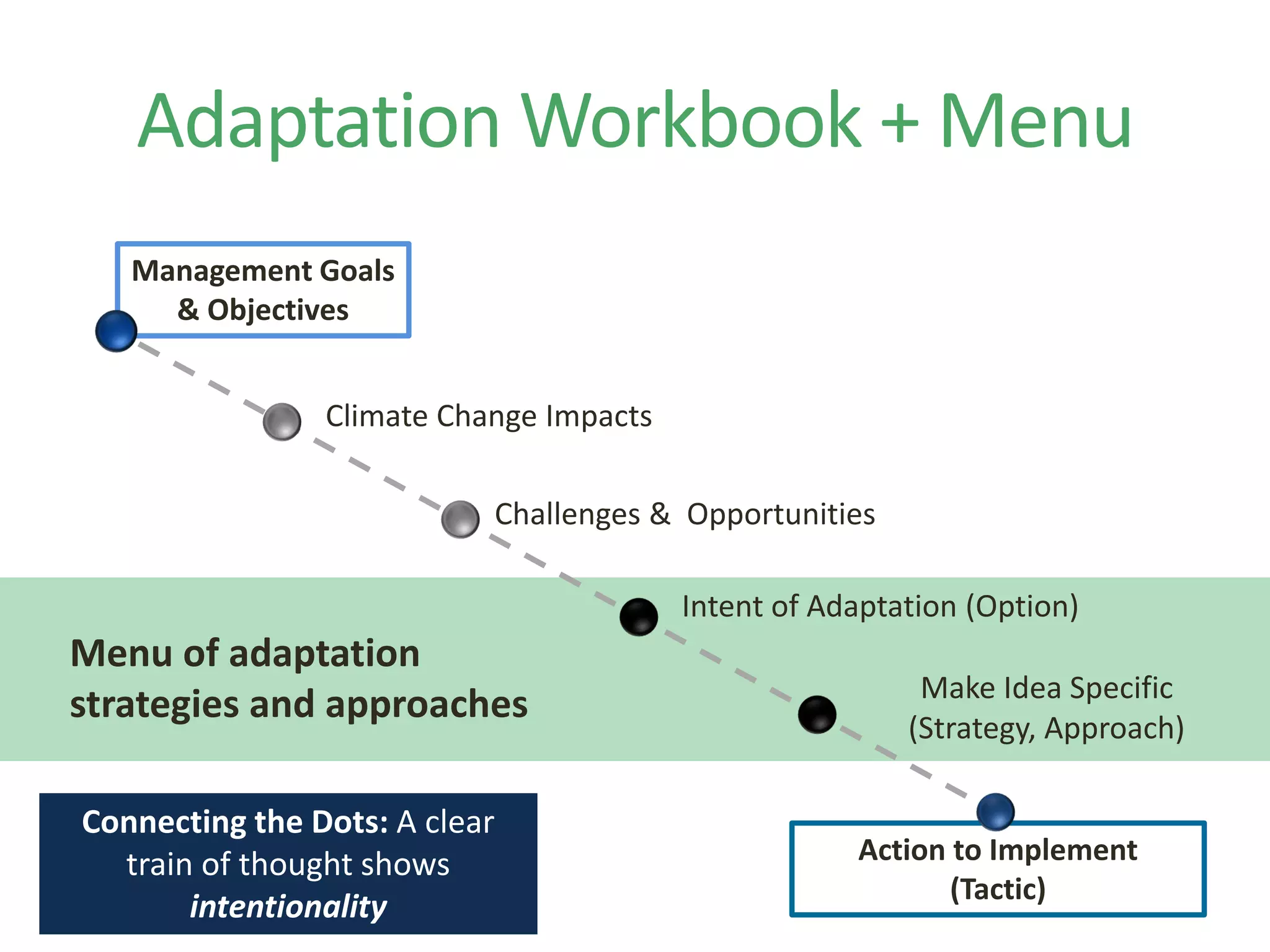

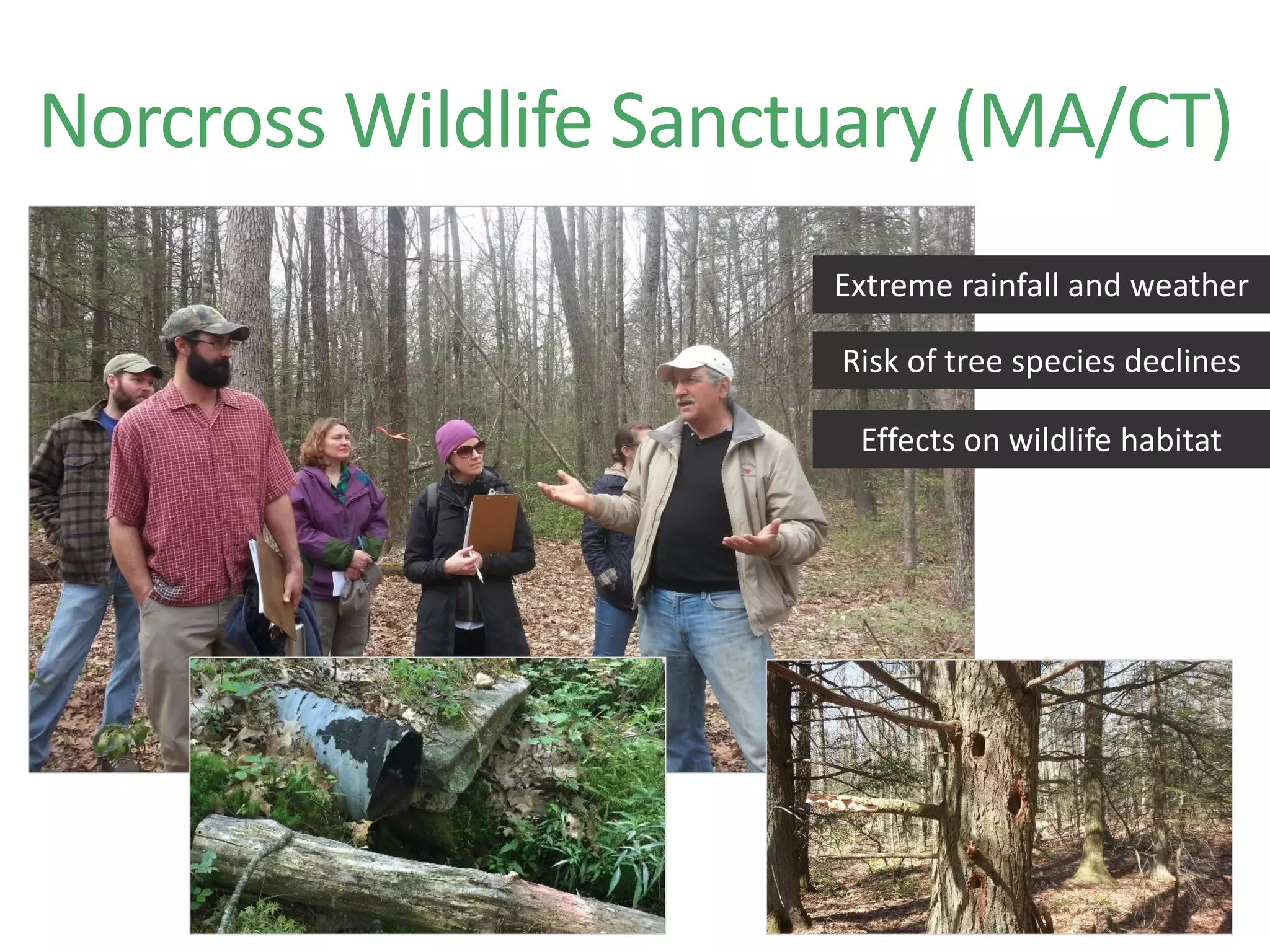

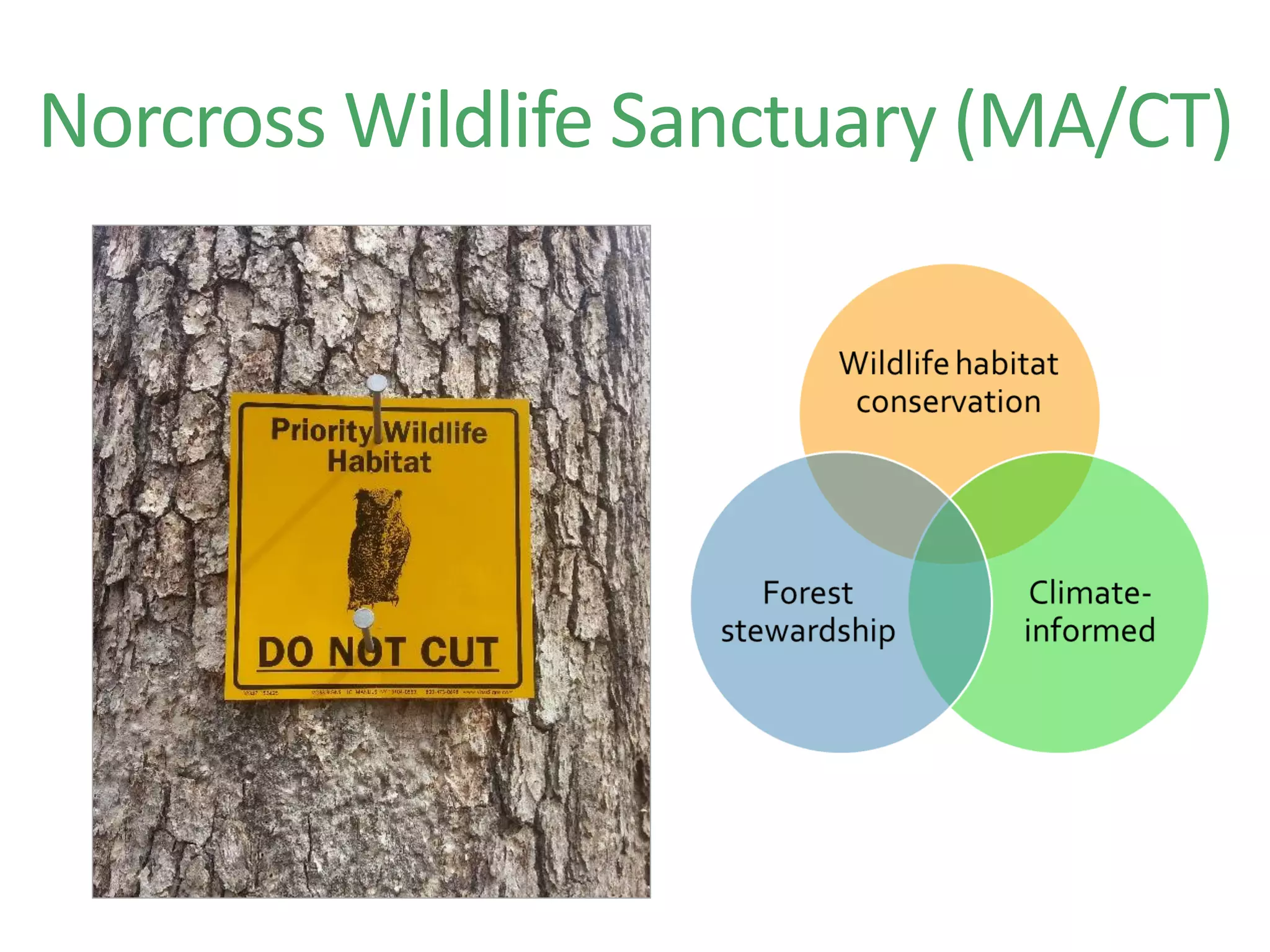

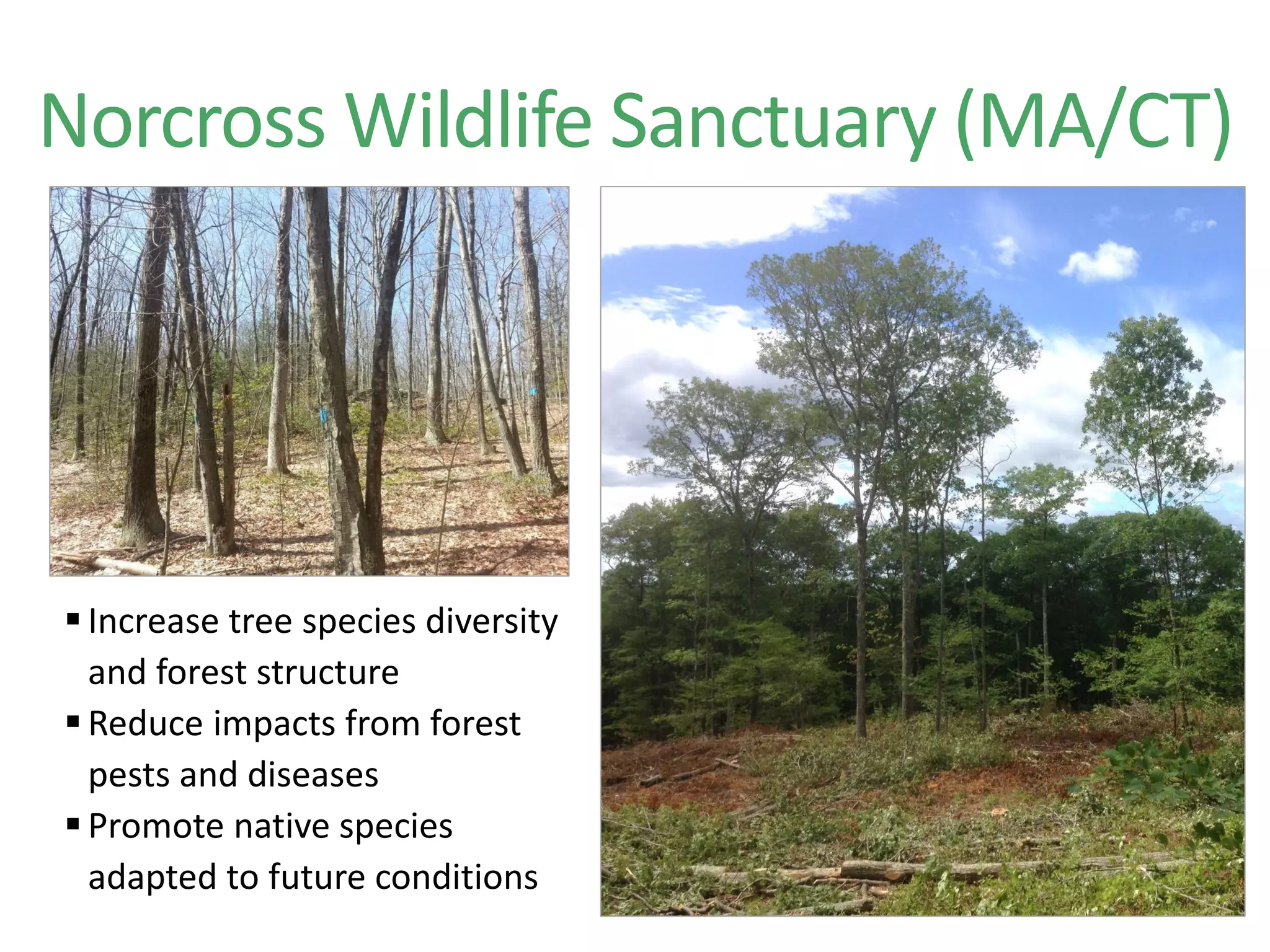

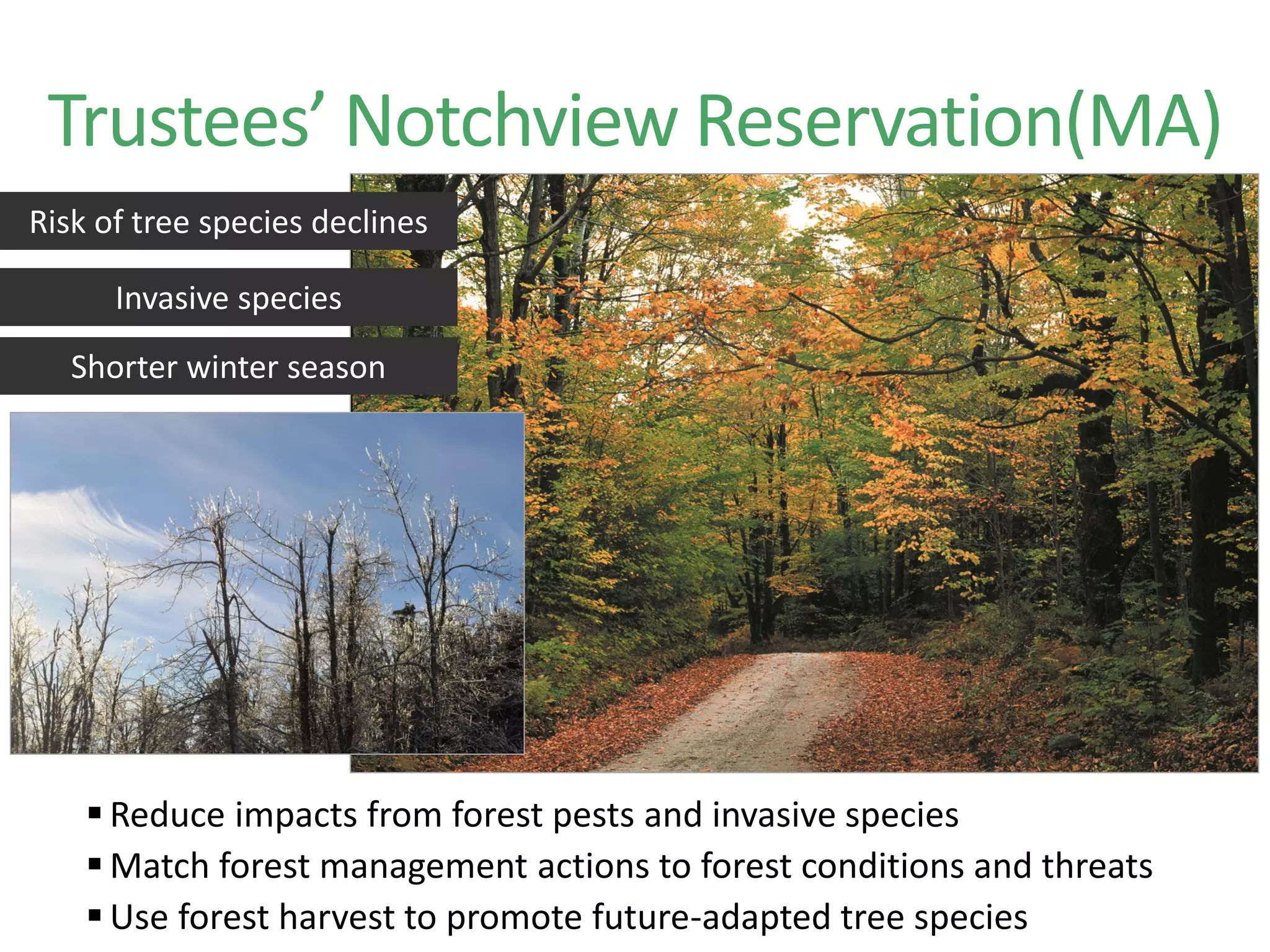

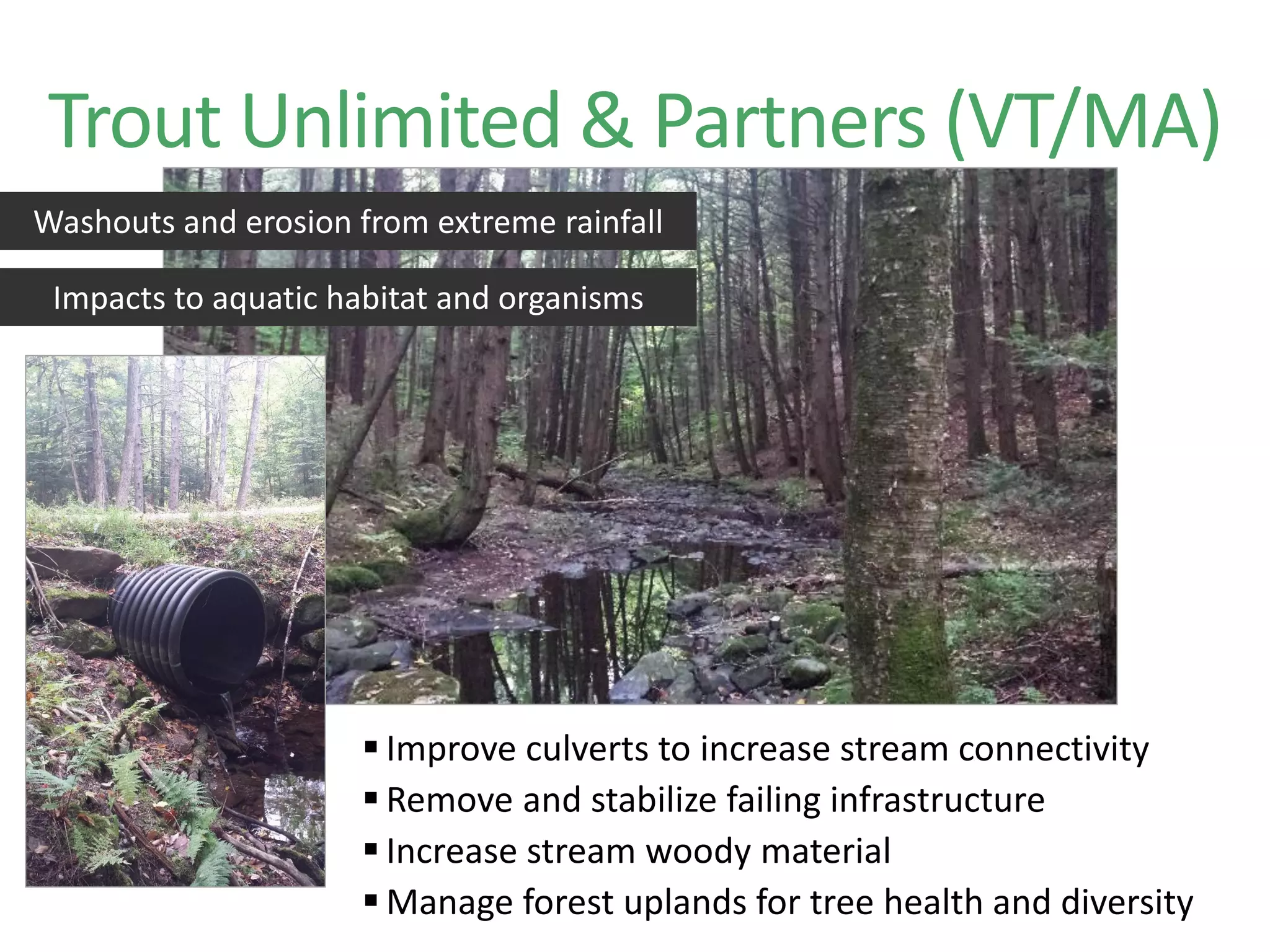

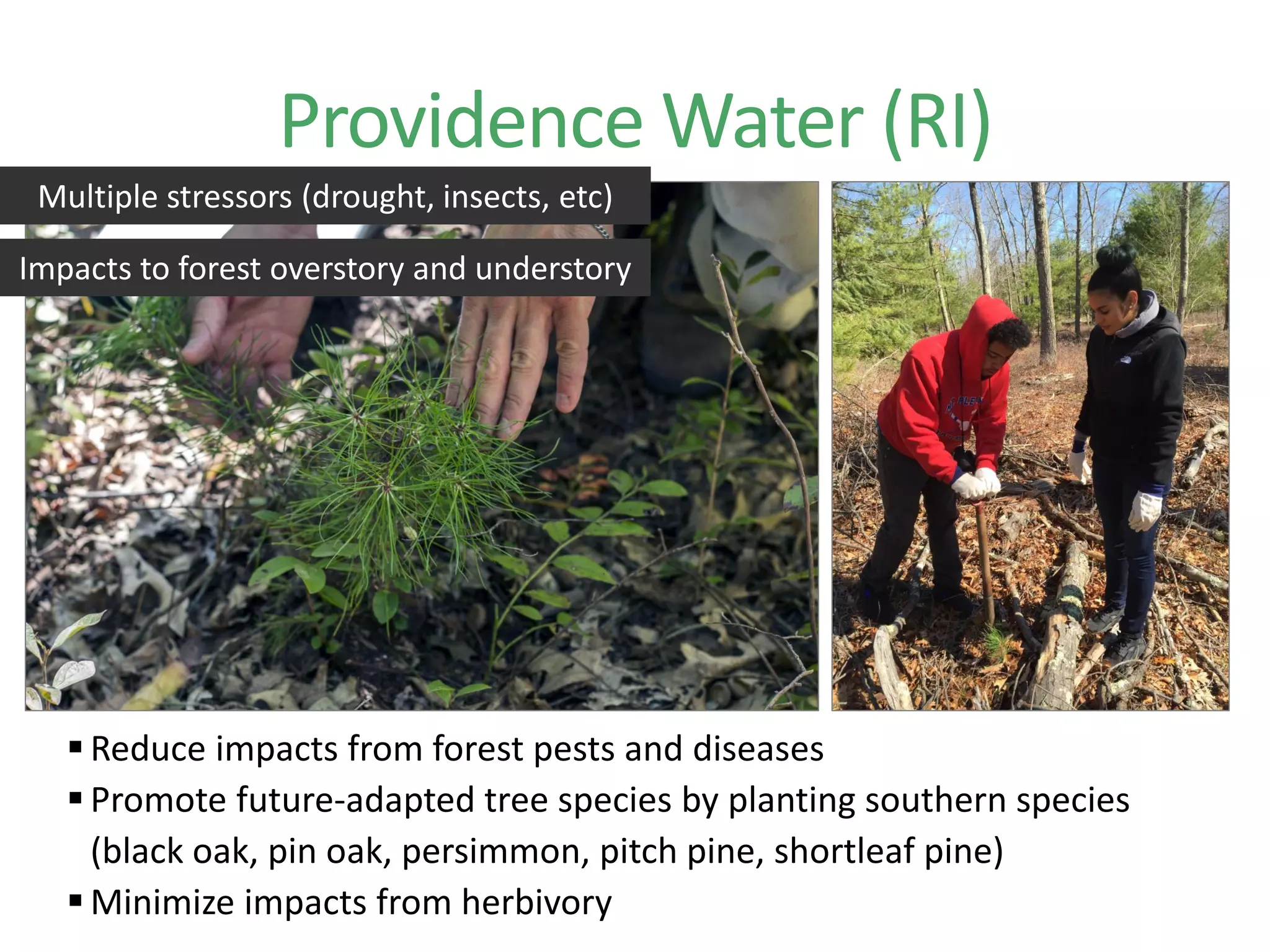

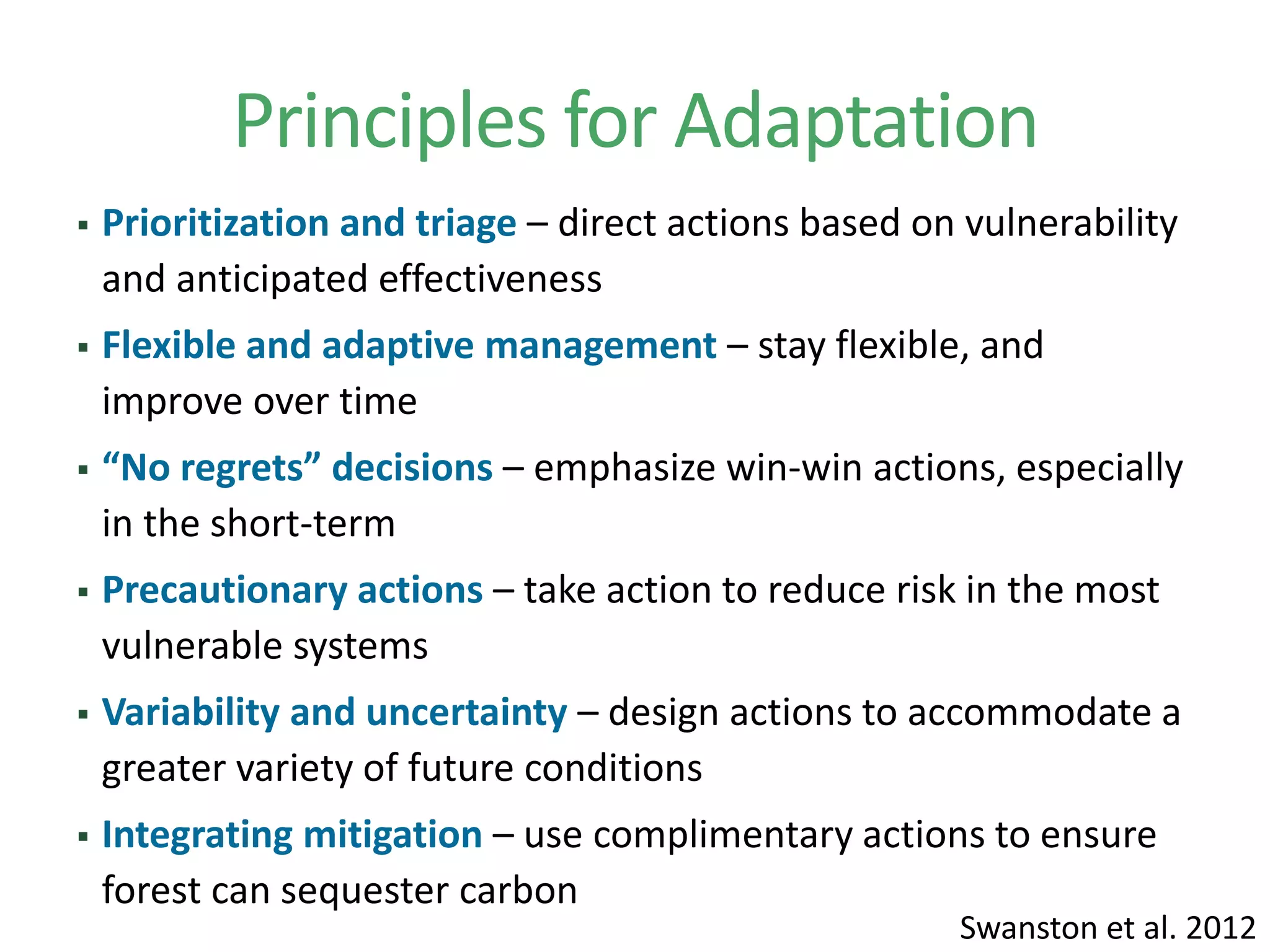

The document discusses the implications of climate change on forests and the importance of adaptation strategies tailored to specific ecosystems and management goals. It outlines a framework for assessing climate impacts, identifying adaptation actions, and emphasizes that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Key adaptation approaches include enhancing ecosystem resilience, managing species diversity, and implementing flexible management practices to address the varied impacts of climate change.