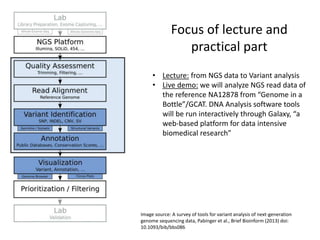

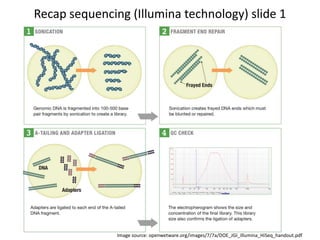

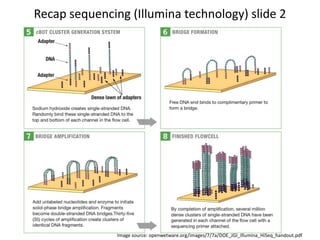

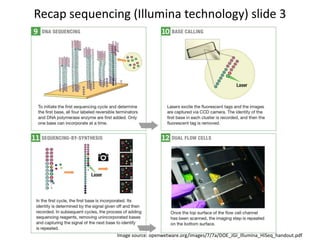

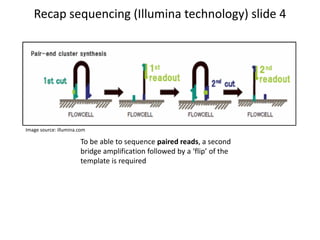

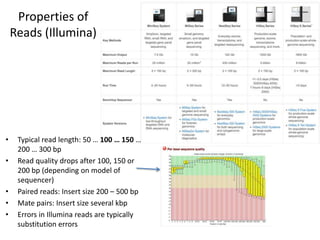

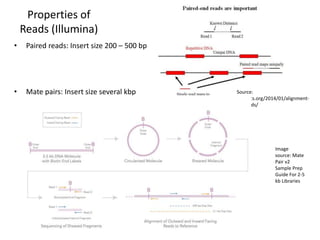

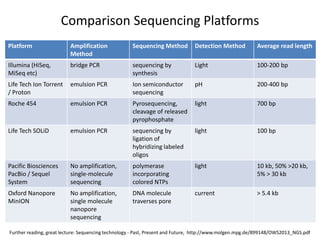

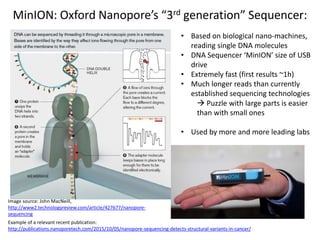

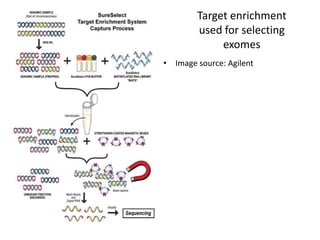

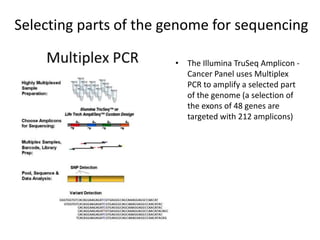

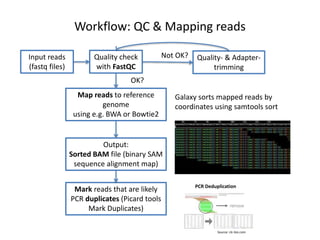

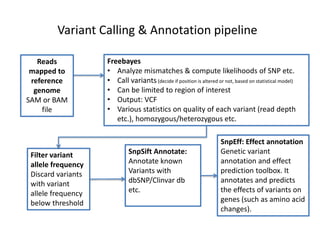

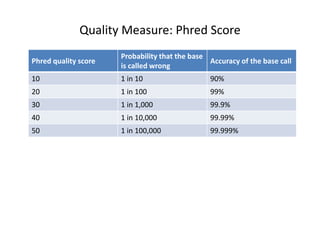

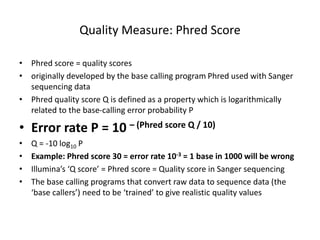

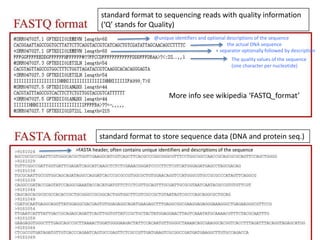

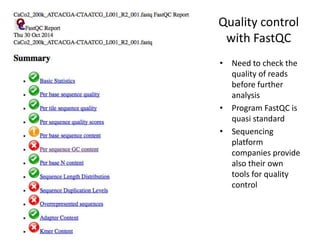

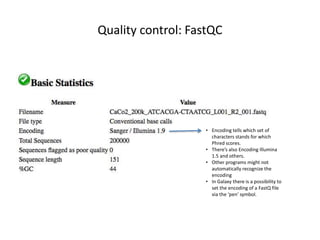

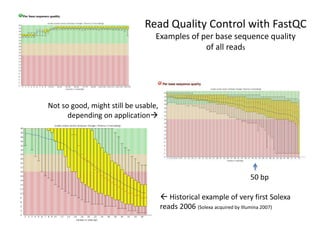

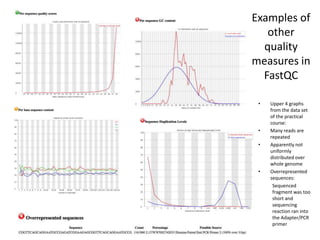

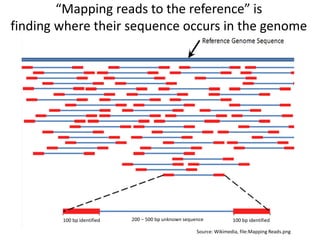

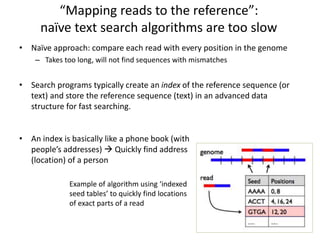

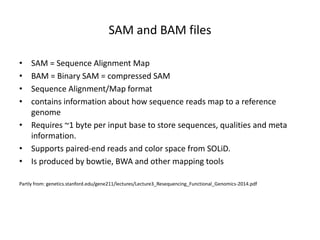

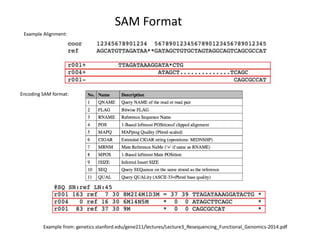

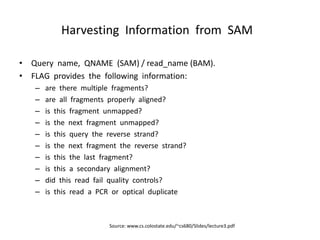

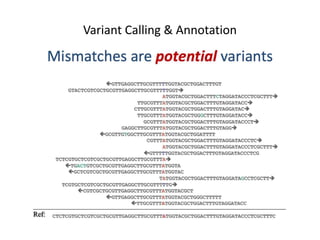

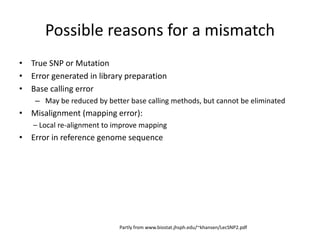

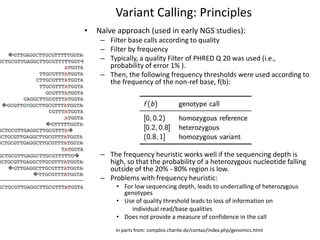

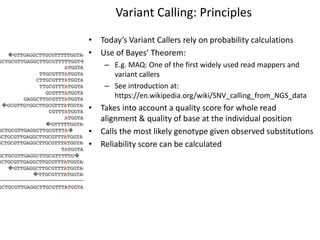

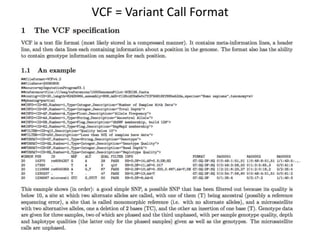

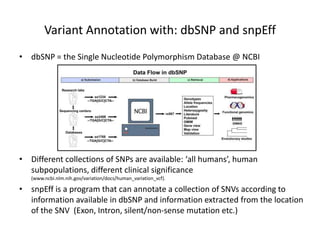

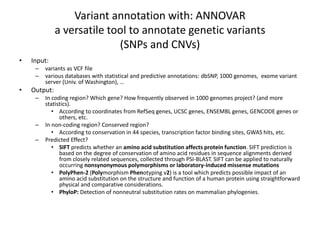

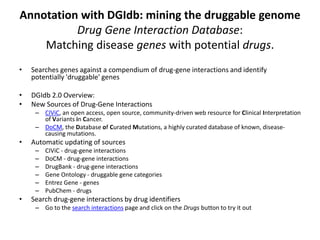

This document provides an overview of variant analysis from next-generation sequencing data. It begins with introductions to the CCA-Drylab@VUmc, TraIT, and Galaxy projects. The focus of the lecture is explained to be variant analysis from NGS data using interactive demos in Galaxy. Background is provided on Illumina sequencing technology and properties of sequencing reads. Key steps in variant analysis are outlined, including quality control and read mapping, variant calling and annotation using tools like FastQC, BWA, FreeBayes, and SnpEff. Formats for storing sequencing data and variants are also introduced, such as FASTQ, SAM/BAM, and VCF.