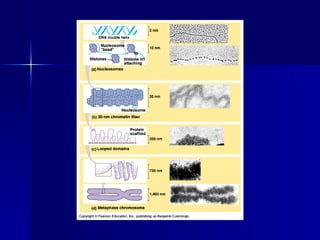

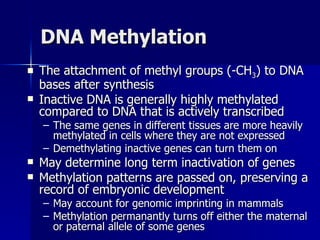

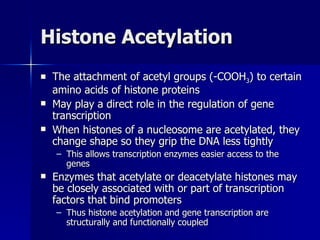

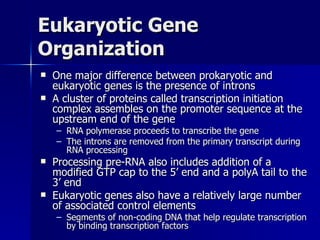

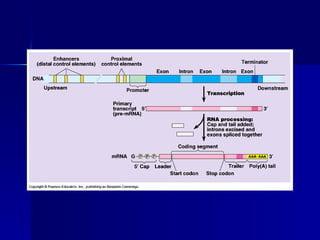

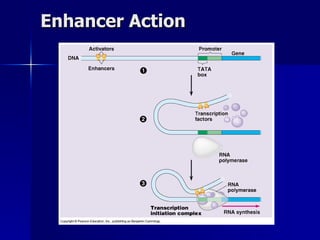

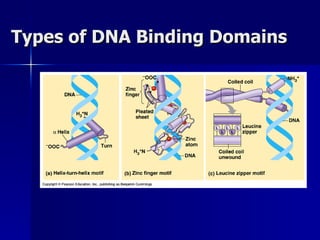

Eukaryotic gene regulation involves complex organization and packaging of DNA into chromatin. Gene expression is controlled at multiple levels, including chromatin modification, transcription initiation, and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Transcription factors play a key role in regulating transcription by binding to enhancer and promoter elements to recruit RNA polymerase and initiate transcription of specific genes.