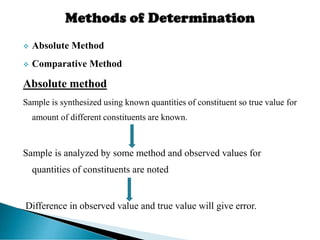

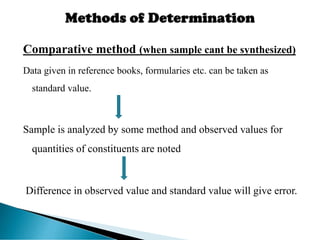

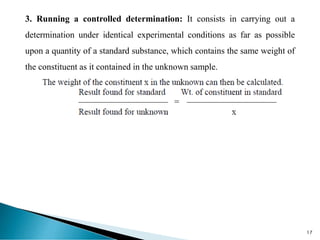

This document discusses methods for determining and classifying errors in chemical analysis. It describes two main categories of errors: systematic (determinate) errors, which can be identified and corrected, and random (indeterminate) errors, which cannot be attributed to a single cause. Determinate errors include personal errors by the analyst, errors due to faulty instruments or impure reagents, and methodic errors related to the analysis technique. Indeterminate errors are accidental and beyond the analyst's control. The document also provides examples of different types of errors and methods for minimizing systematic errors, such as running blanks, calibration, controlled determinations, and independent verification of results.