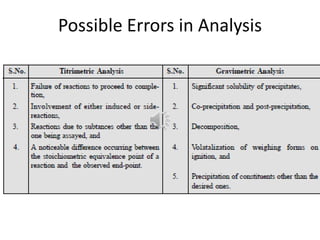

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in pharmaceutical analysis. There are two main categories of errors: determinate (systematic) errors and indeterminate (random) errors. Determinate errors have identifiable causes and include personal errors, instrumental errors, reagent errors, and errors due to methodology. Indeterminate errors cannot be identified and include random fluctuations. The document provides examples of different types of errors and methods that can be used to minimize errors, such as calibration, blank determinations, and using multiple analytical methods.