The document discusses vector spaces and related concepts:

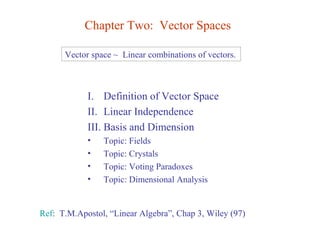

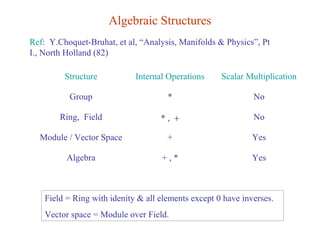

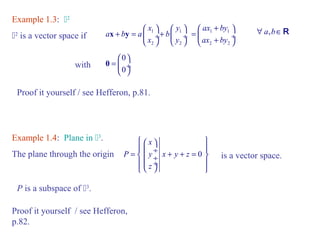

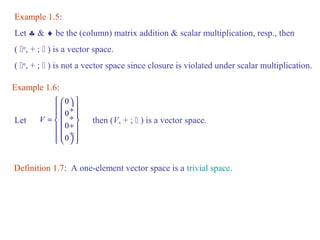

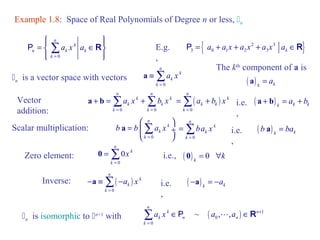

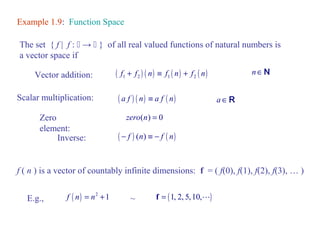

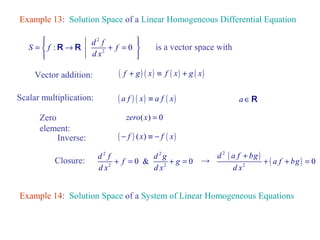

1) It defines a vector space as a set V with vector addition and scalar multiplication operations that satisfy certain properties. Examples of vector spaces include R2, the plane in R3, and the space of real polynomials.

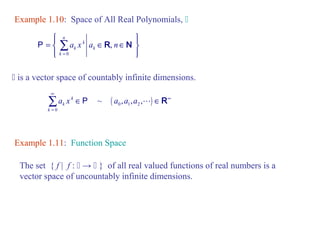

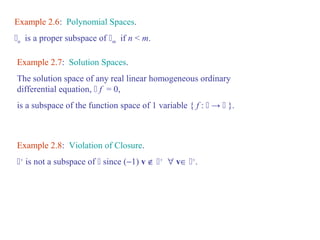

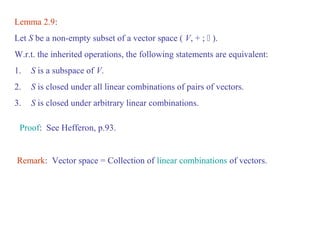

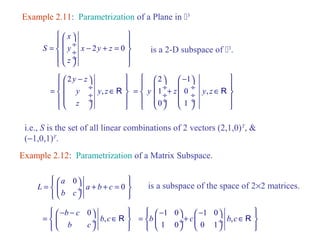

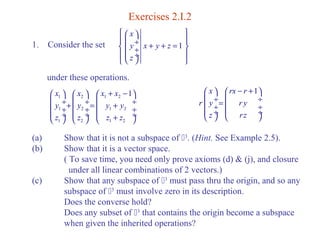

2) A subspace is a subset of a vector space that is closed under vector addition and scalar multiplication and thus forms a vector space with the inherited operations. Examples given include the x-axis in Rn and solution spaces of linear differential equations.

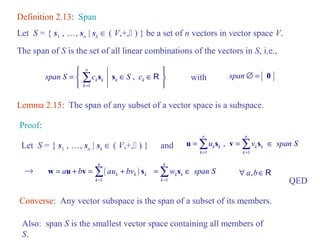

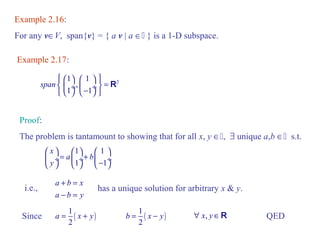

3) The span of a set of vectors is the smallest subspace that contains those vectors, consisting of all possible linear combinations of the vectors in the set.

![Definition in Conventional Notations

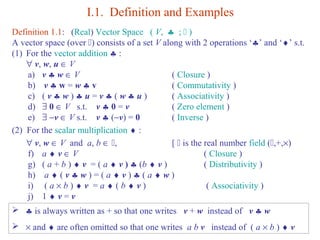

Definition 1.1: (Real) Vector Space ( V, + ; )

A vector space (over ) consists of a set V along with 2 operations ‘+’ and ‘ ’ s.t.

(1) For the vector addition + :

" v, w, u Î V

a) v + w Î V ( Closure )

b) v + w = w + v ( Commutativity )

c) ( v + w ) + u = v + ( w + u ) ( Associativity )

d) $ 0 Î V s.t. v + 0 = v ( Zero element )

e) $ -v Î V s.t. v -v = 0 ( Inverse )

(2) For the scalar multiplication :

" v, w Î V and a, b Î , [ is the real number field (,+,´) ]

a) a v Î V ( Closure )

b) ( a + b ) v = a v + b v ( Distributivity )

c) a ( v + w ) = a v + a w

d) ( a ´ b ) v = a ( b v ) = a b v ( Associativity )

e) 1 v = v](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/definitionofvectorspace-141022040414-conversion-gate02/85/Definition-ofvectorspace-6-320.jpg)

![2. Because ‘span of’ is an operation on sets we naturally consider how it

interacts with the usual set operations. Let [S] º Span S.

(a) If S Í T are subsets of a vector space, is [S] Í [T] ?

Always? Sometimes? Never?

(b) If S, T are subsets of a vector space, is [ S È T ] = [S] È [T] ?

(c) If S, T are subsets of a vector space, is [ S Ç T ] = [S] Ç [T] ?

(d) Is the span of the complement equal to the complement of the span?

3. Find a structure that is closed under linear combinations, and yet is not

a vector space. (Remark. This is a bit of a trick question.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/definitionofvectorspace-141022040414-conversion-gate02/85/Definition-ofvectorspace-25-320.jpg)