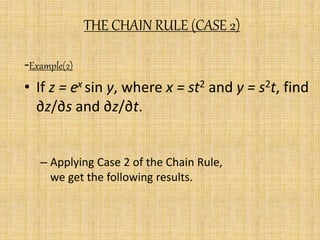

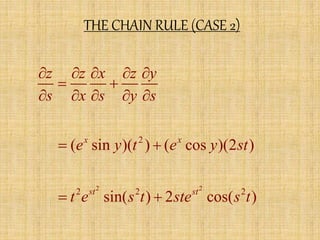

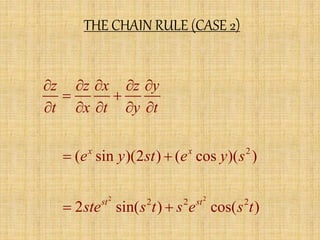

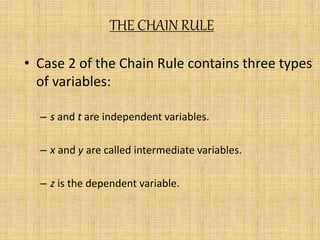

The document discusses the chain rule and Euler's theorem.

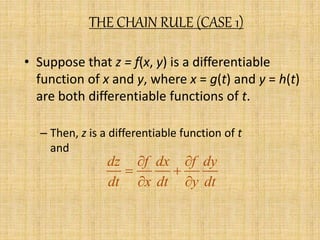

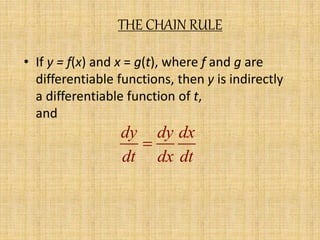

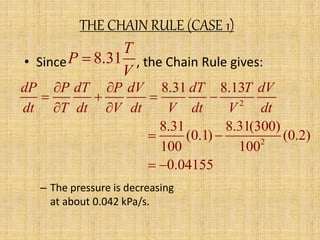

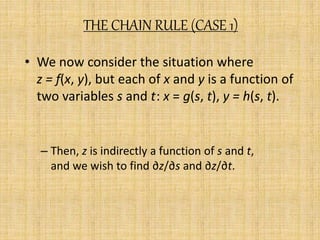

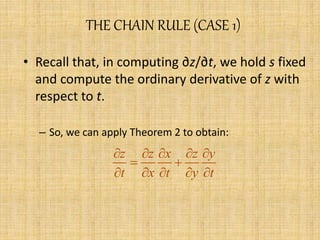

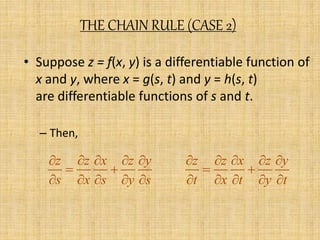

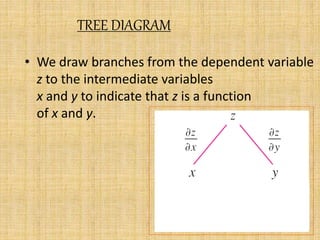

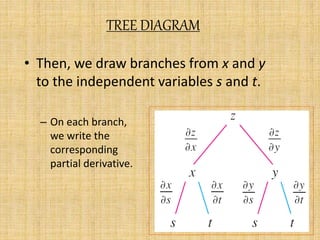

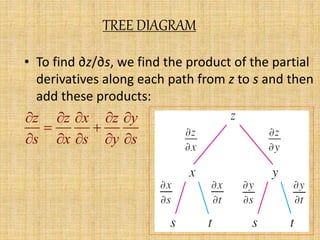

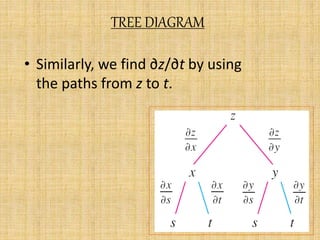

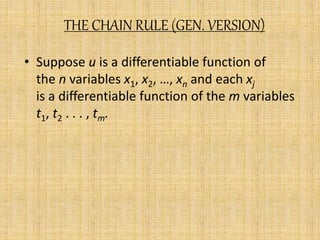

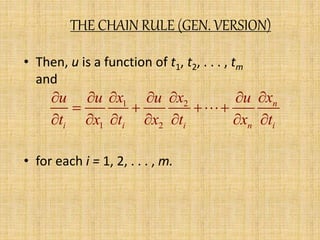

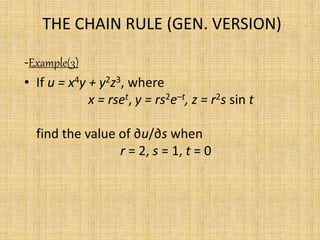

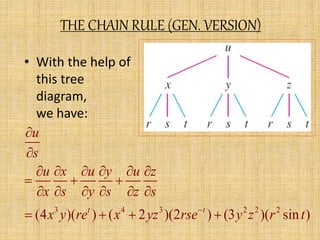

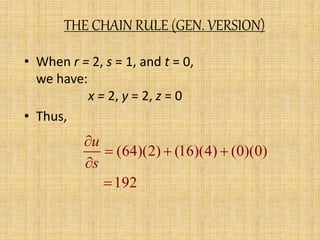

It explains the chain rule for functions of single, multiple, and general variables. The chain rule gives rules for finding the derivative of a composite function.

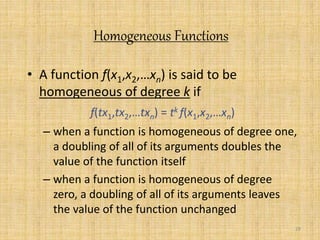

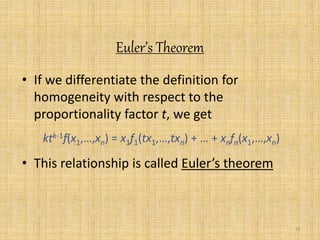

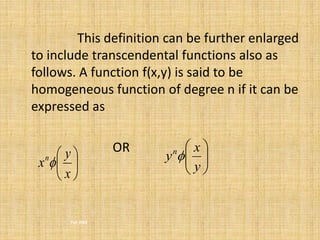

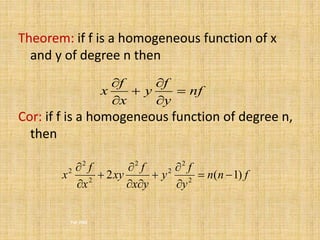

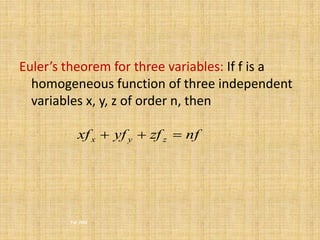

It also explains that if a function is homogeneous of degree k, its partial derivatives will be homogeneous of degree k-1. Euler's theorem relates the values of a homogeneous function to the values of its partial derivatives. The theorem is extended to functions of multiple variables.

![Modified EULER’s theorem

If Z is a Homogeneous function of degree n in

the variables x and y and z=f(u)

f u

( )

f u

' ( )

n

u

x

y

y

u

x

If z is a homogeneous function of degree n in

the variables x and y and z=f(u)

2

u

2 ( )[ ' ( ) 1],

u

2

2

2

u

2

2

2

g u g u

x y

xy

y

y

x

x

f u

( )

' ( )

( )

f u

g u n

where](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentiation-141022041619-conversion-gate01/85/Partial-differentiation-36-320.jpg)