The document discusses vector calculus concepts including:

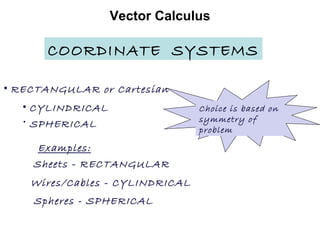

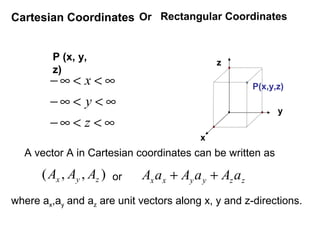

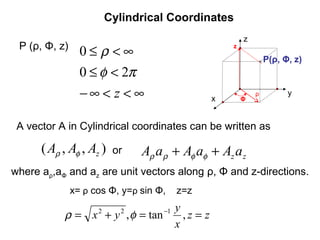

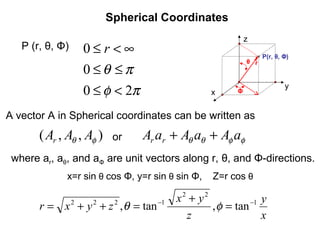

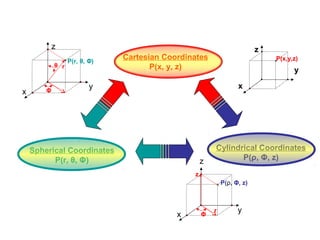

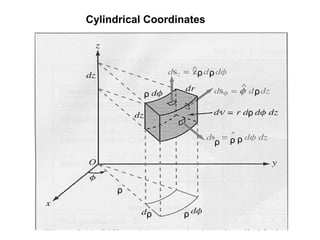

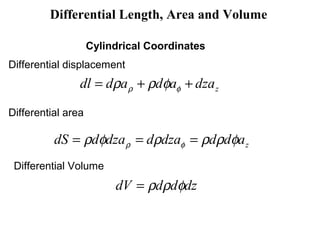

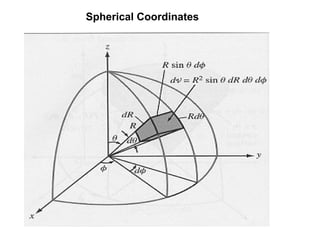

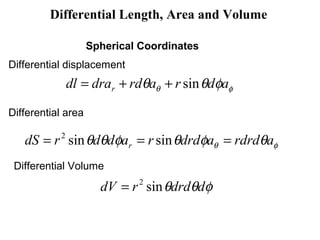

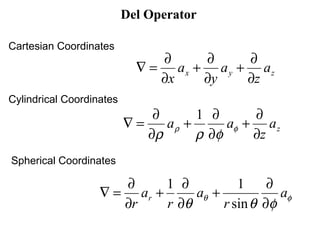

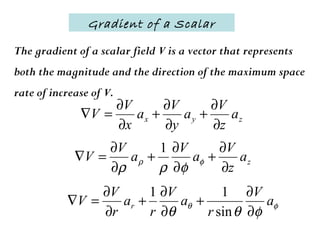

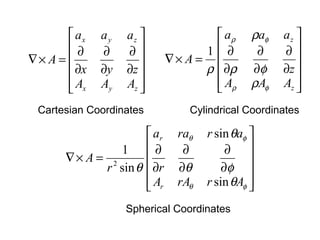

1) Coordinate systems used in vector calculus problems including rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinates.

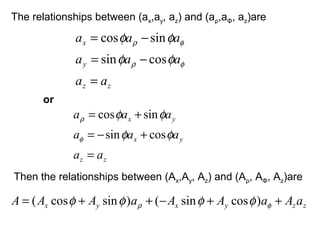

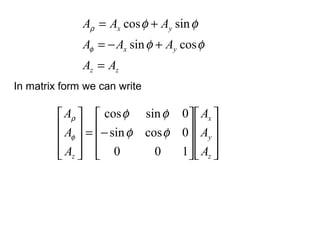

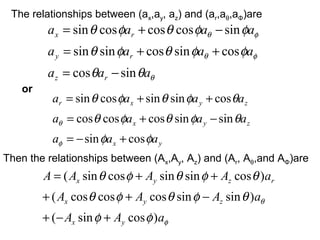

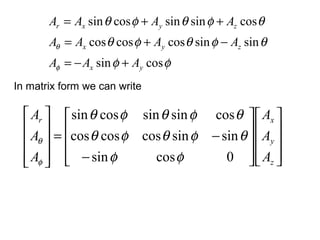

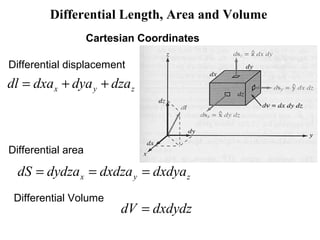

2) How to write vectors and their components in each coordinate system.

3) Relationships between vectors in different coordinate systems using transformation matrices.

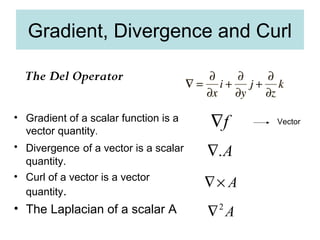

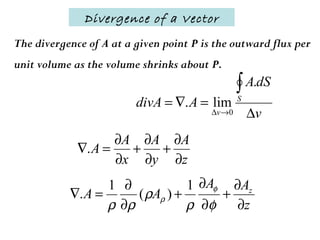

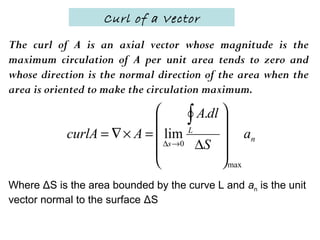

4) Concepts of gradient, divergence, and curl and their definitions and representations in different coordinate systems.

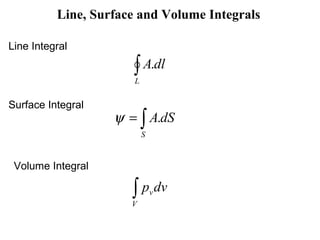

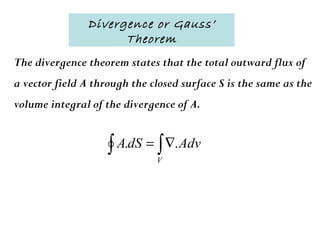

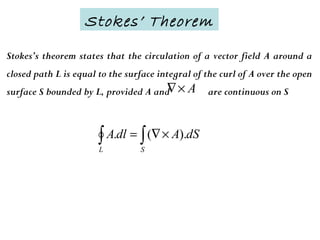

5) Theorems relating integrals, including the divergence theorem and Stokes' theorem.