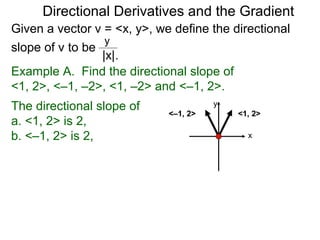

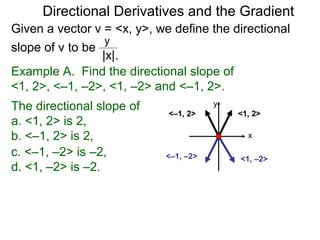

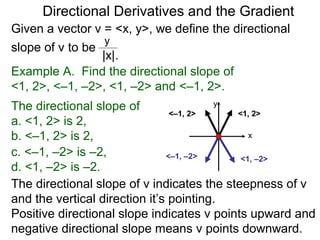

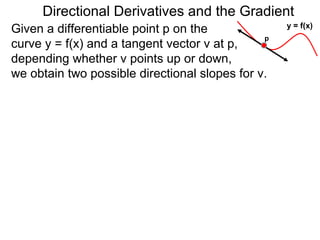

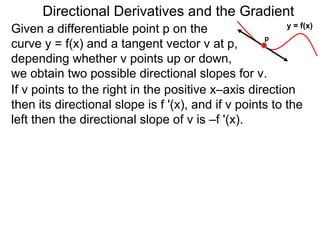

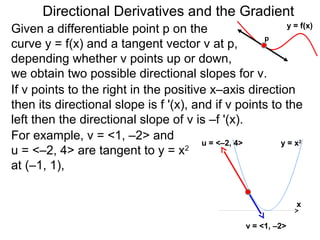

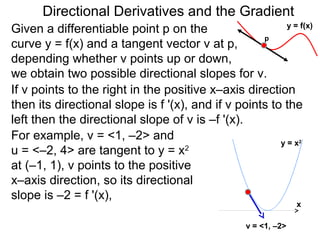

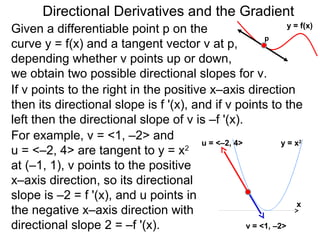

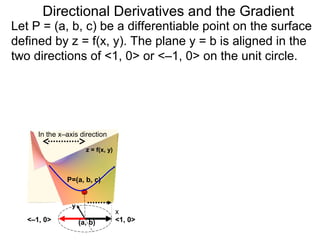

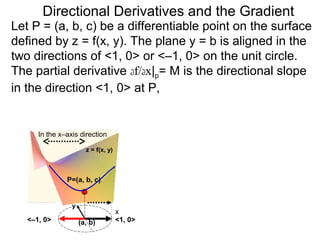

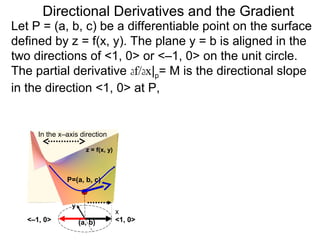

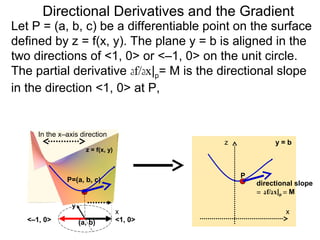

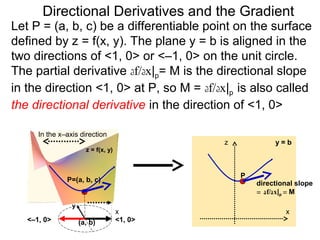

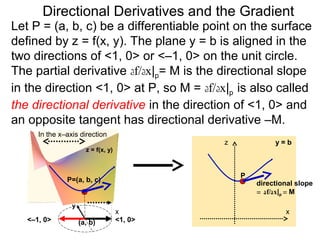

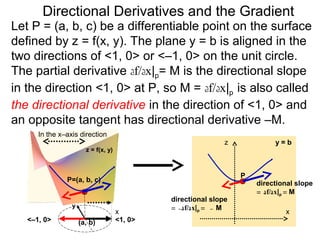

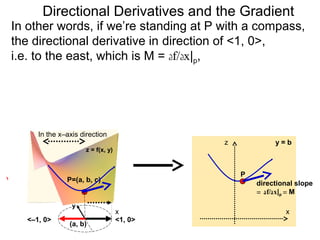

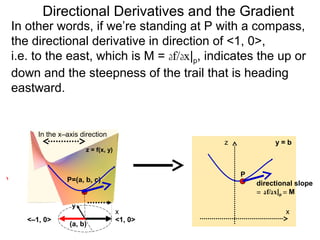

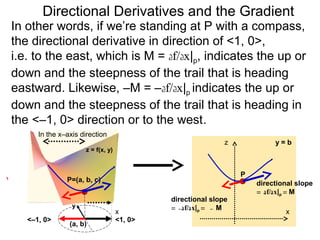

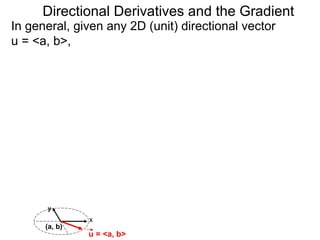

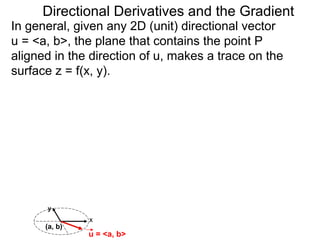

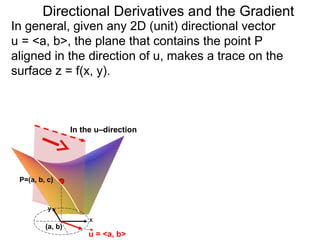

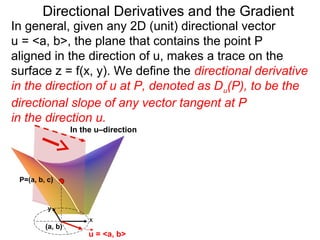

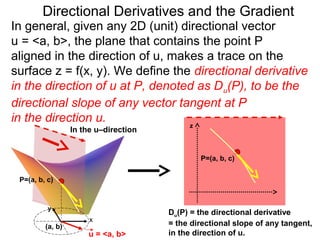

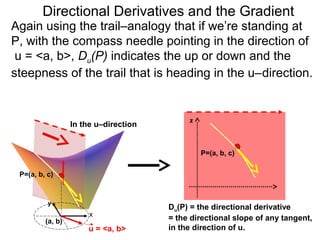

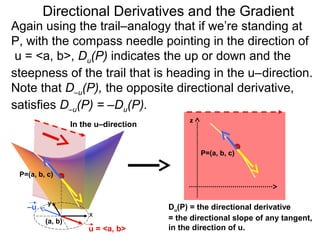

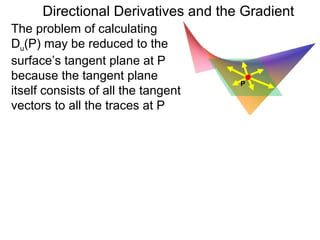

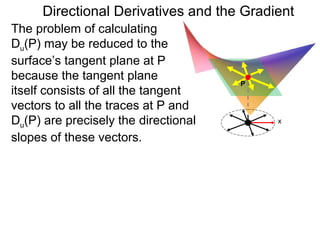

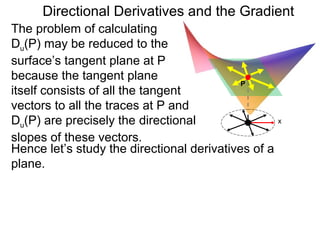

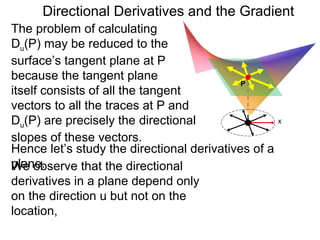

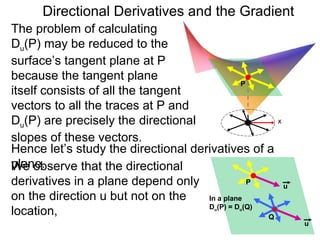

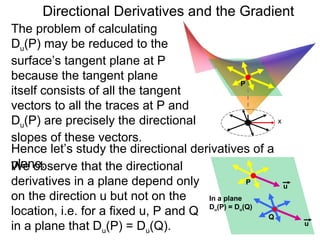

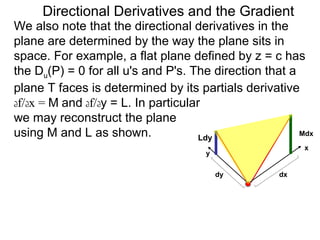

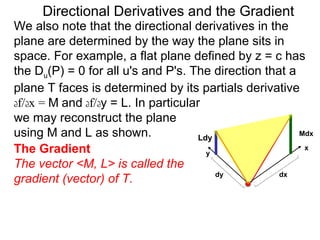

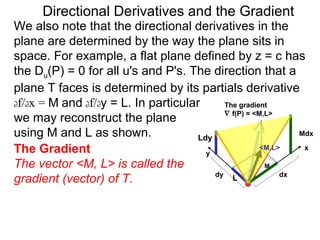

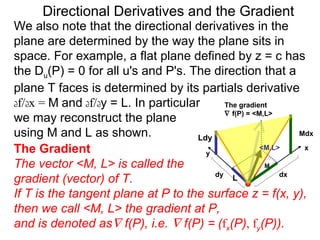

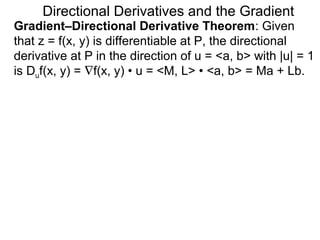

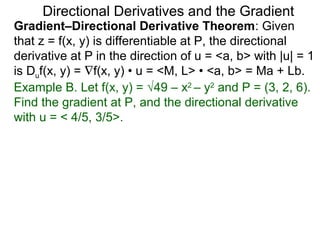

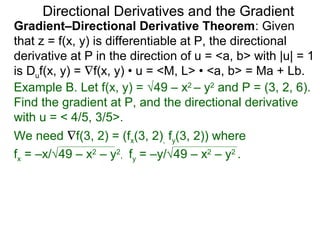

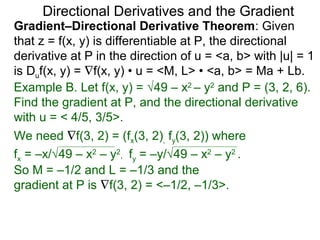

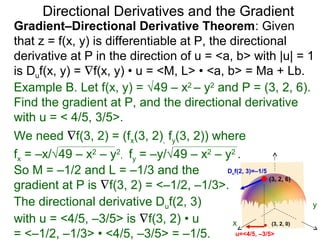

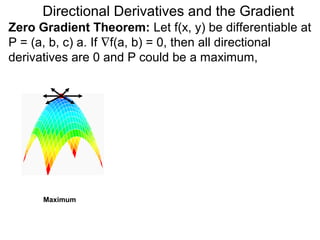

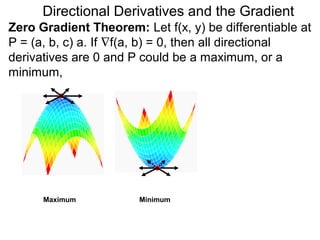

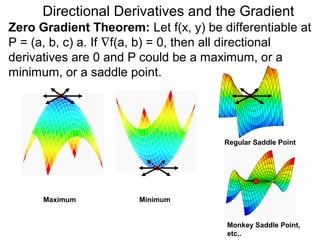

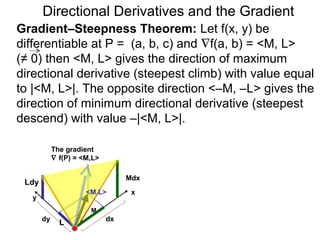

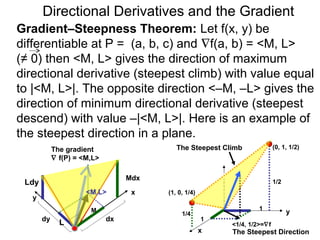

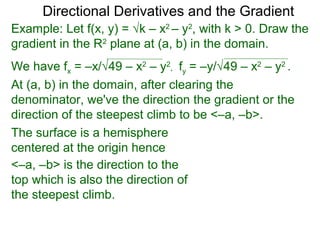

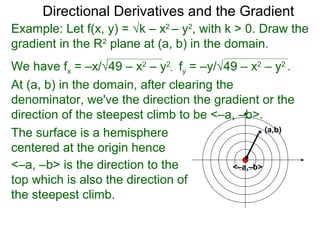

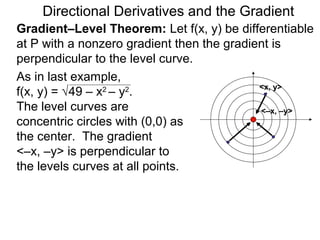

The document discusses directional derivatives and the gradient. It defines the directional slope of a vector v as the ratio of the y-component to the x-component of v. It then gives an example of calculating the directional slopes of several vectors. It explains that the directional slope indicates the steepness and direction of v. For a differentiable function f(x), the directional derivative in the direction of the unit vector <1,0> is the partial derivative df/dx, while the opposite direction has derivative -df/dx.