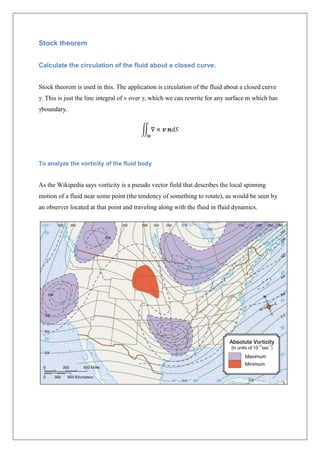

This document discusses the application of vector integration in various domains. It begins by defining vector calculus concepts like del, gradient, curl, and divergence. It then presents several theorems of vector integration. Next, it explains how vector integration can be used to find the rate of change of fluid mass and analyze fluid circulation, vorticity, and the Bjerknes Circulation Theorem regarding sea breezes. It also discusses using vector calculus concepts in electricity and magnetism.