This document discusses line integrals and Green's theorem. It defines line integrals as integrals of scalar or vector fields along a curve, parameterized by arc length. Line integrals may depend on the path taken between two points, but are path-independent for conservative vector fields. Green's theorem relates line integrals around a closed curve to a double integral over the enclosed region, equating the line integral to the curl of the vector field integrated over the region. An example demonstrates using Green's theorem to evaluate a line integral as a double integral.

![8/19/2022 Berhanu G(Dr) 19

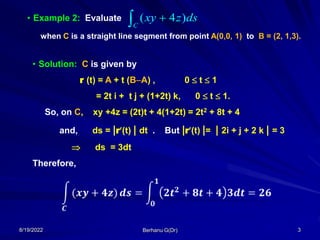

(x,y,0)

u

(x,y,z)

z=v

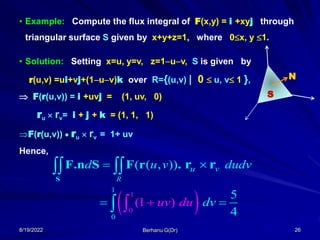

2. The lateral surface of a vertical circular cylinder of radius and

height h can be parameterized using:

3. If S is given by x+y+z=1 over x,y[0,1] , then S can be

parameterized using

x=u, y=v, z=1uv, where 0 u 1, and 0 v 1.

x=cos(u), 0 u 2,

y=sin(u),

z=v, 0 v h.

Thus,

r(u,v) =cos(u)i +sin(u)j + v k,

when 0 u 2, and 0 vh.

Thus, r(u,v) =ui + v j + (1uv) k, when 0 u, v 1.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lineintegral-220819201347-352bdf98/85/Line-integral-ppt-19-320.jpg)

![8/19/2022 Berhanu G(Dr) 20

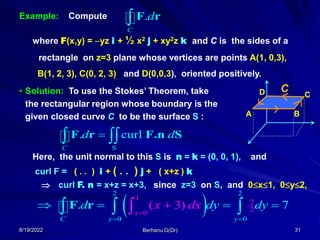

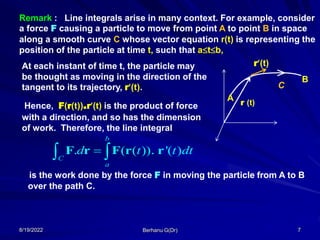

• Normal vector: If a surface S is given by a differentiable

• In general, if S is given by z=f(x,y), for x[a,b] and y[c,d] , then

putting x=u and y=v, we can represent S by

• r(u,v) = u i + v j + f(u,v) k, where a u b & c v d

r(u,v) = x(u,v) i + y(u,v) j + z(u,v) k, for a u b & c v d ,

the, a normal vector N to S , called outward normal, is given by

N = ru rv

v -constant

u -const

ru

rv

N

where ru & rv are partial derivatives of

r(u,v) w.r.t u & v, respectively

In this case, the unit outward normal of S is given by

|| ||

u v

u v

r r

r r

n

when N = ru rv 0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lineintegral-220819201347-352bdf98/85/Line-integral-ppt-20-320.jpg)