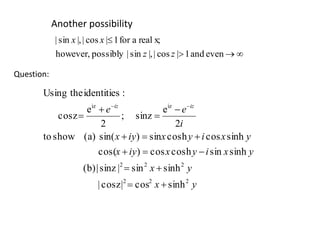

This document discusses functions of a complex variable. It introduces complex numbers and their representations. It covers topics like complex differentiation using Cauchy-Riemann equations, analytic functions, Cauchy's integral theorem, and contour integrals. Functions of a complex variable provide tools for physics concepts involving complex quantities like wavefunctions. Cauchy's integral theorem states that the contour integral of an analytic function over a closed path is zero.

![In polar coordinates, we parameterize

and , and have

which is independent of r.

Cauchy’s integral theorem

– If a function f(z) is analytical (therefore single-valued) [and its partial

derivatives are continuous] through some simply connected region R, for

every closed path C in R,

i

rez

diredz i

2

0

1

1exp

22

1

dni

r

dzz

i

n

c

n

1-nfor1

-1nfor0

{

0 dzzf

c](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit1-170125100150/85/Unit1-21-320.jpg)