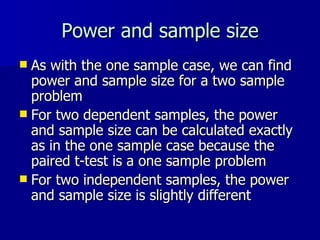

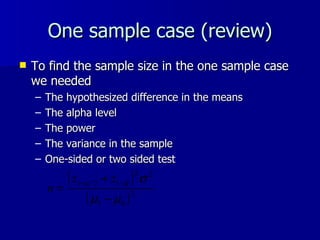

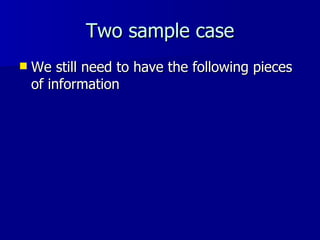

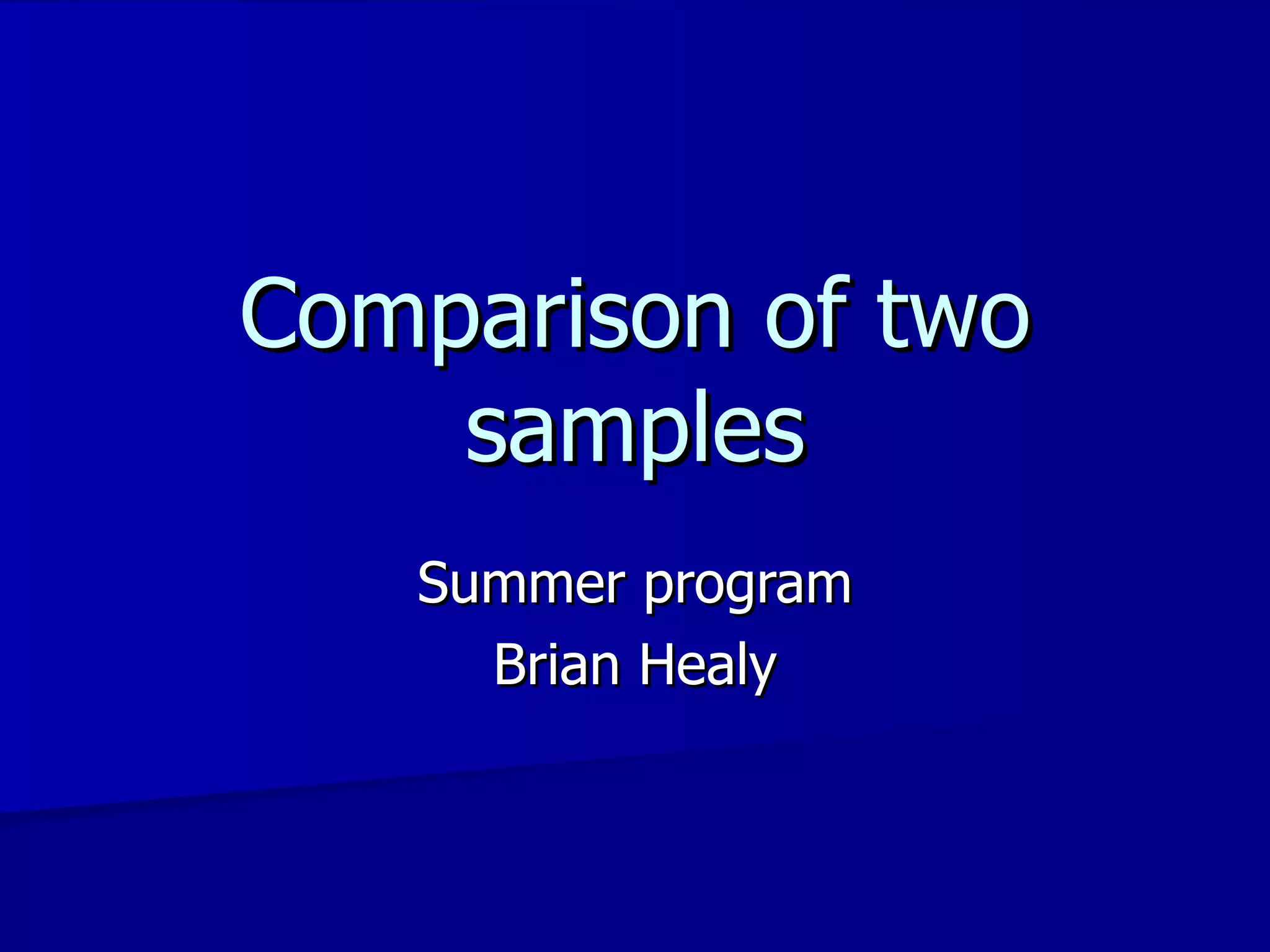

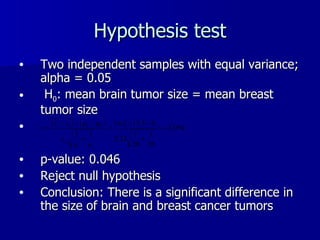

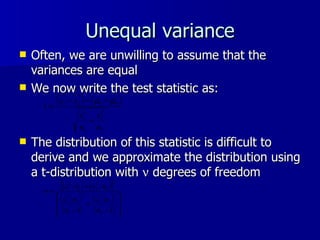

The document discusses comparing measurements from two physicians who measured tumor volumes. A paired t-test was used to test if the measurements significantly differed. The t-test showed no significant difference between physicians. Additionally, two sample t-tests were used to compare tumor volumes between different cancer types, finding significant differences between brain and breast cancers and brain and liver cancers.

![Paired t-test in R data<-read.table(G:\\BIO232\\Summer\\pairedscans.dat”, header=F) dr1<-data[,1]; dr2<-data[,2] t.test(dr1, dr2, paired=T) The output provides the p-value and the confidence interval Paired t-test data: data[, 1] and data[, 2] t = -0.6456, df = 19, p-value = 0.5262 alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 95 percent confidence interval: -1.0180279 0.5380279 sample estimates: mean of the differences -0.24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/twosamplet-test-100421122132-phpapp01/85/Two-sample-t-test-14-320.jpg)

![R code If we only had the test statistics above, we can calculate the test statistic and then compare it to the t-distribution using pt(-2.054 ,df=46) to determine the area in the lower tail How do we convert this into the appropriate p-value? With the full data, we can use data<-read.table(“cancer.dat”,header=T) gr<-data[,1]; size<-data[,2] t.test(size[(gr==0)], size[(gr==1)], var.equal=T)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/twosamplet-test-100421122132-phpapp01/85/Two-sample-t-test-26-320.jpg)

![R output Two Sample t-test data: size[(gr == 0)] and size[(gr == 1)] t = -2.054, df = 46, p-value = 0.04568 alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 95 percent confidence interval: -2.65174438 -0.02682705 sample estimates: mean of x mean of y 16.15000 17.48929](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/twosamplet-test-100421122132-phpapp01/85/Two-sample-t-test-27-320.jpg)

![R output > t.test(size[(gr==0)],size[(gr==2)]) Welch Two Sample t-test data: size[(gr == 0)] and size[(gr == 2)] t = -3.1666, df = 22.48, p-value = 0.00439 alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 95 percent confidence interval: -5.288291 -1.105827 sample estimates: mean of x mean of y 16.15000 19.34706](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/twosamplet-test-100421122132-phpapp01/85/Two-sample-t-test-32-320.jpg)

![Example > var.test(size[(gr==1)],size[(gr==0)]) F test to compare two variances data: size[(gr == 1)] and size[(gr == 0)] F = 1.719, num df = 27, denom df = 19, p-value = 0.2247 alternative hypothesis: true ratio of variances is not equal to 1 95 percent confidence interval: 0.710335 3.904512 sample estimates: ratio of variances 1.719033 > var.test(size[(gr==2)],size[(gr==0)]) F test to compare two variances data: size[(gr == 2)] and size[(gr == 0)] F = 4.1182, num df = 16, denom df = 19, p-value = 0.004156 alternative hypothesis: true ratio of variances is not equal to 1 95 percent confidence interval: 1.589643 11.111060 sample estimates: ratio of variances 4.118214](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/twosamplet-test-100421122132-phpapp01/85/Two-sample-t-test-38-320.jpg)