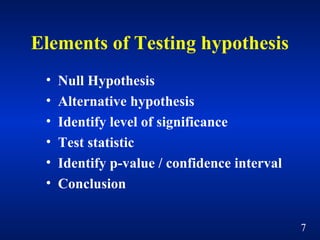

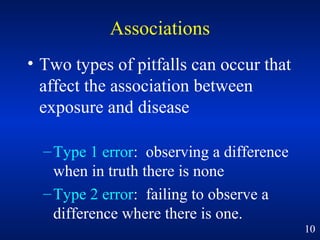

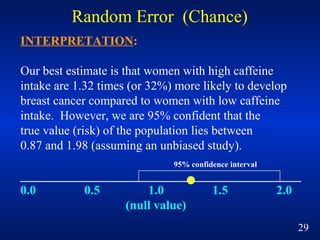

This document discusses key concepts in research methods and biostatistics, including hypothesis testing, random error, p-values, and confidence intervals. It explains that hypothesis testing involves determining if study findings reflect chance or a true effect. The p-value represents the probability of observing results as extreme or more extreme than what was observed by chance alone. A p-value less than 0.05 indicates statistical significance. Confidence intervals provide a range of values that are likely to contain the true population parameter.