This document discusses equivalence relations and cosets from abstract algebra. It contains the following key points:

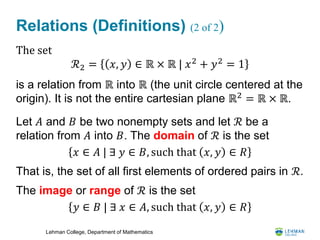

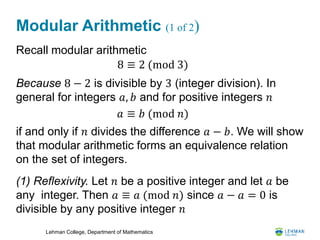

1) It defines equivalence relations as relations that satisfy reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity. Modular arithmetic and group conjugacy are given as examples of equivalence relations.

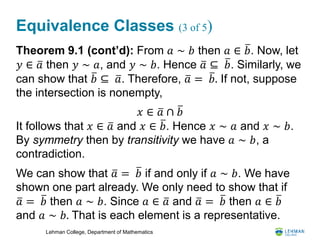

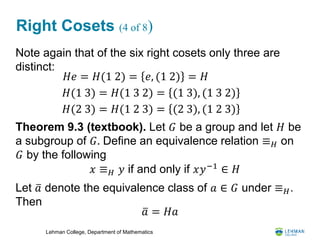

2) It introduces the concept of equivalence classes, which are the subsets of elements related by an equivalence relation. It proves that the equivalence classes partition the set.

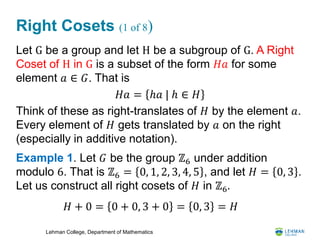

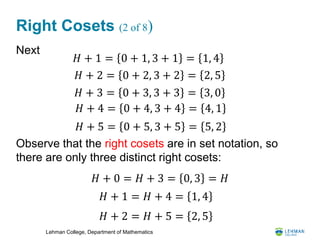

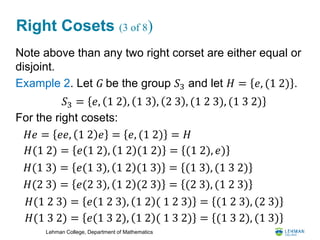

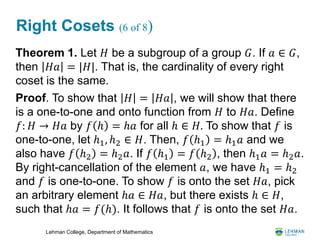

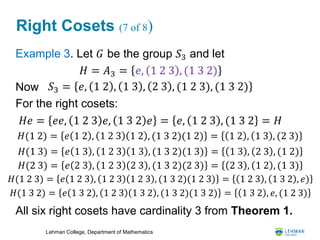

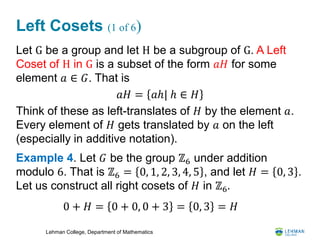

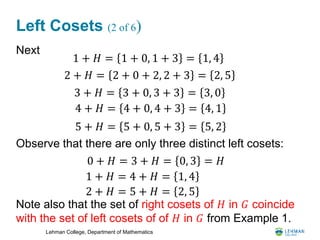

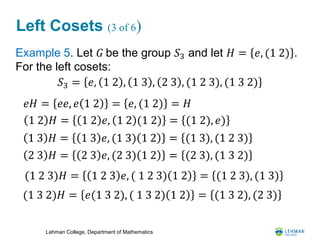

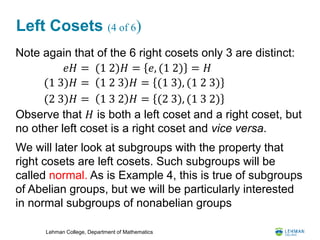

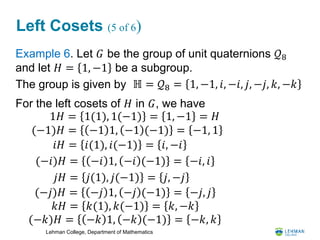

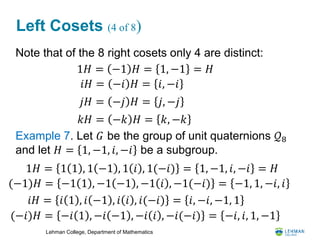

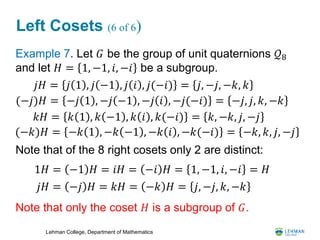

3) It defines right cosets as translations of a subgroup by group elements. Examples are given of finding the right cosets of subgroups of Z6 and S3.