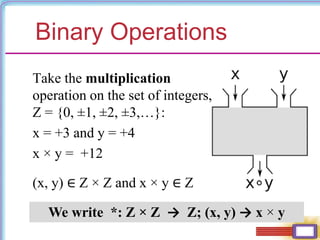

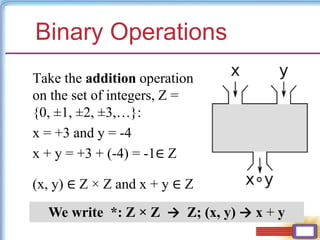

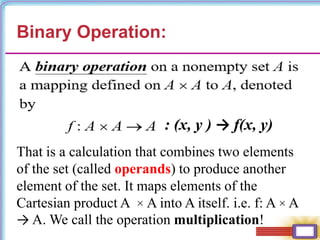

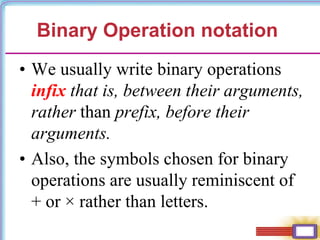

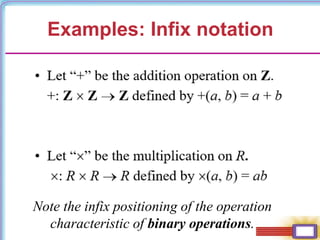

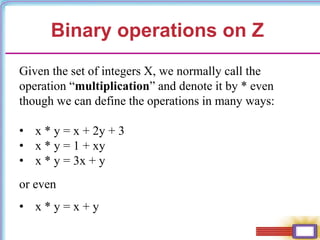

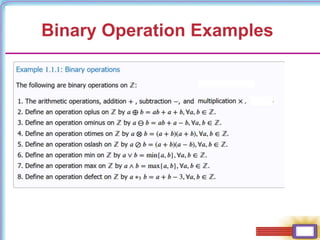

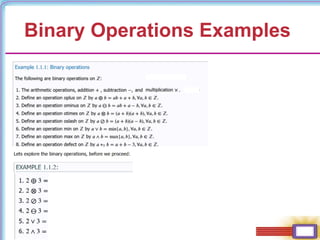

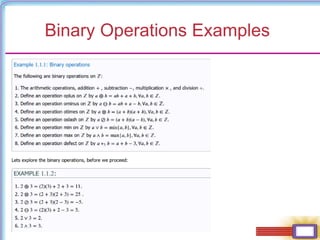

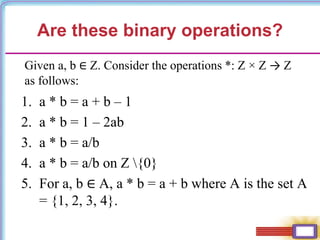

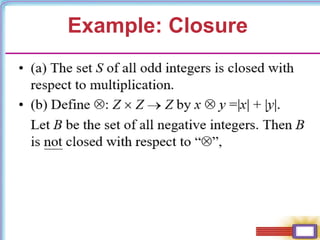

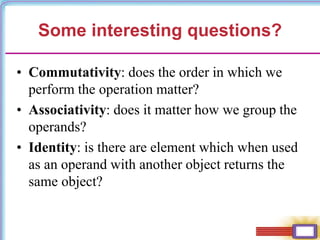

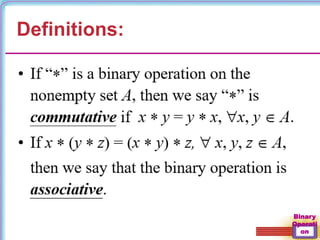

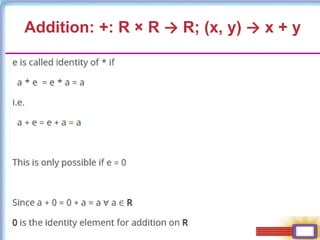

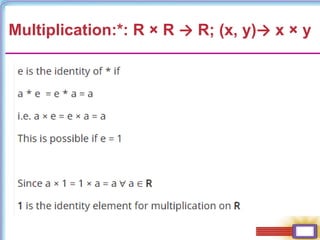

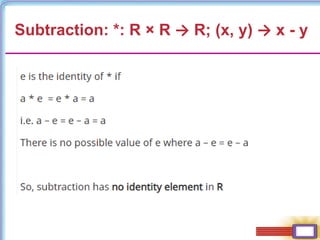

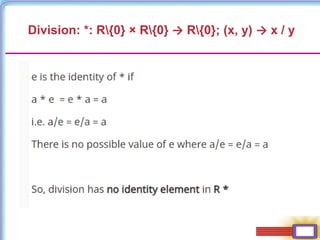

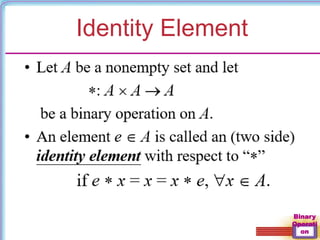

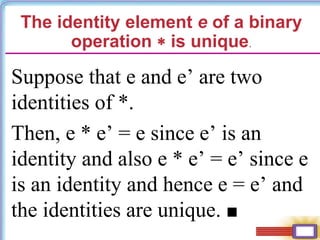

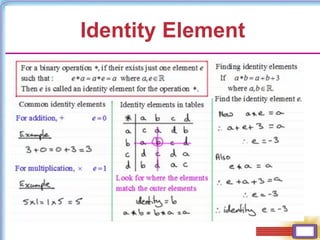

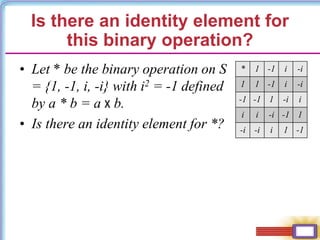

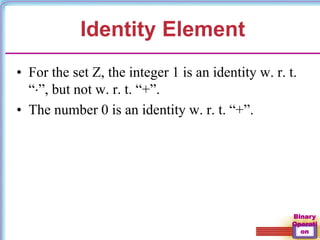

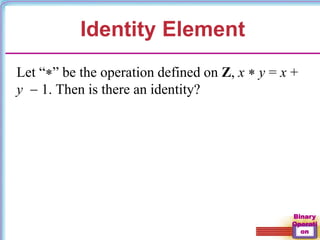

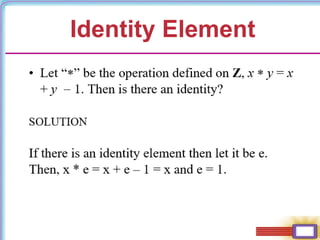

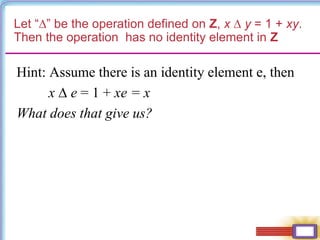

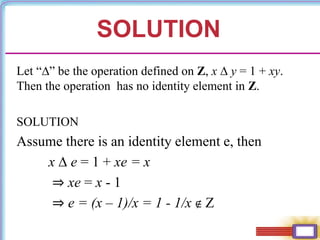

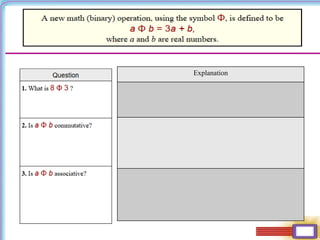

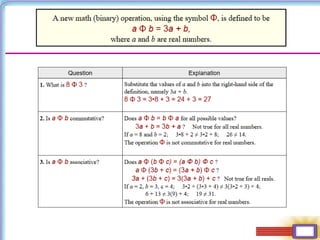

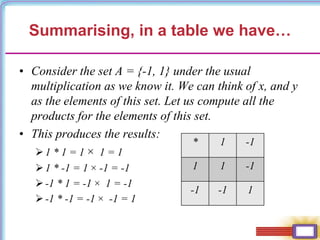

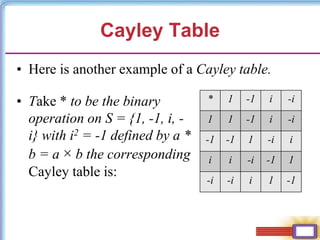

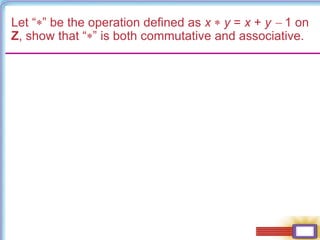

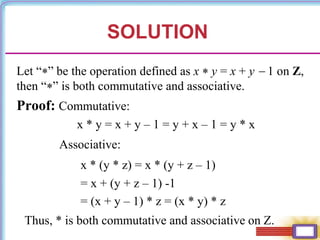

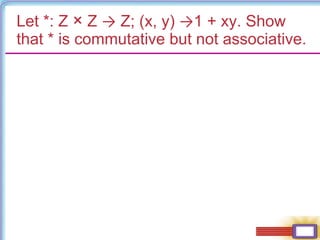

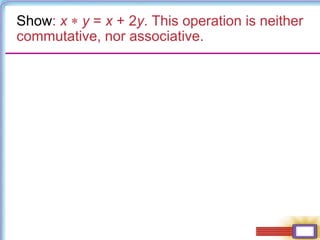

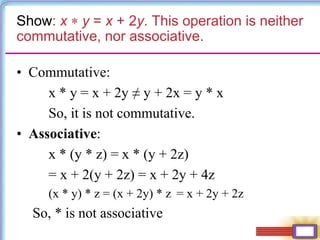

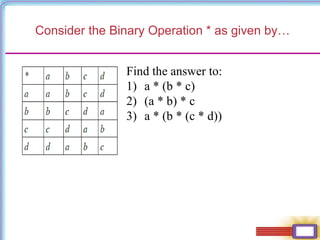

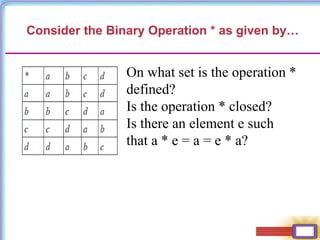

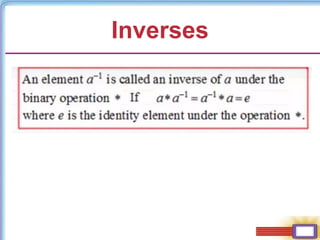

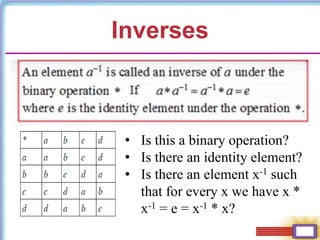

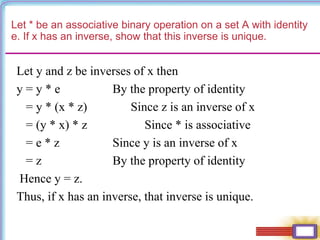

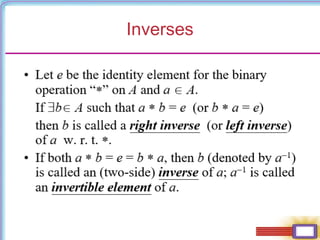

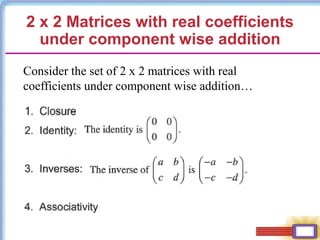

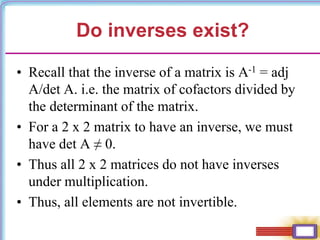

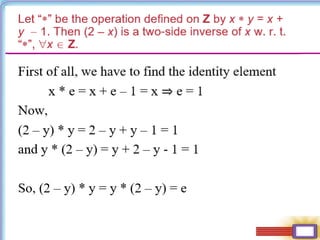

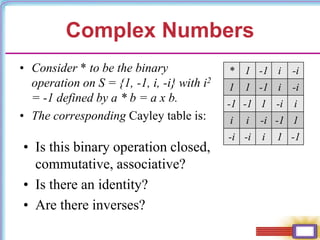

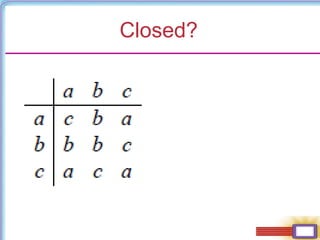

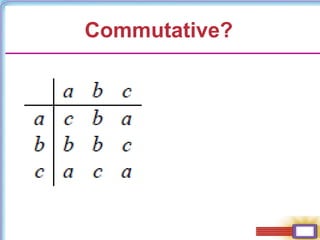

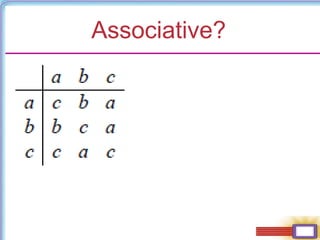

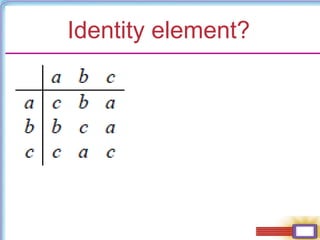

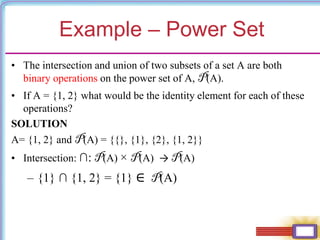

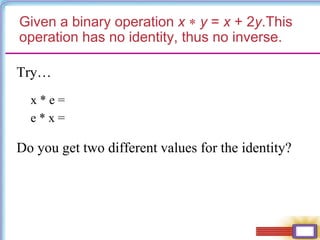

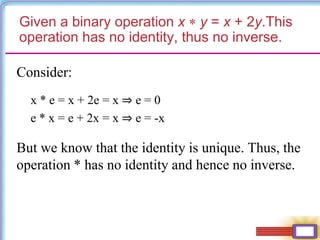

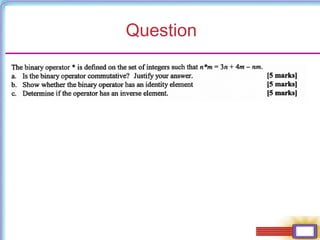

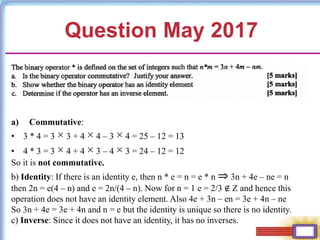

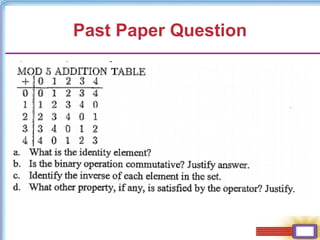

The document discusses binary operations on sets. It provides examples of multiplication and addition operations on the set of integers Z. It introduces the concept of a Cayley table to represent a binary operation on a finite set using a table. The identity element and inverses are discussed. It is noted that the inverse of an element, if it exists, is unique. Examples are provided to check if binary operations are closed, commutative, associative, and have identities and inverses.