This document is an introductory lecture on real analysis, focusing primarily on set theory and its fundamental concepts, including definitions of sets, elements, and their relationships. It explains mathematical notations, operations, logical relations, and proofs, as well as the concepts of subsets and set operations. Additionally, it outlines the importance of distinguishing between different types of statements and conditions in mathematical proofs.

![Example

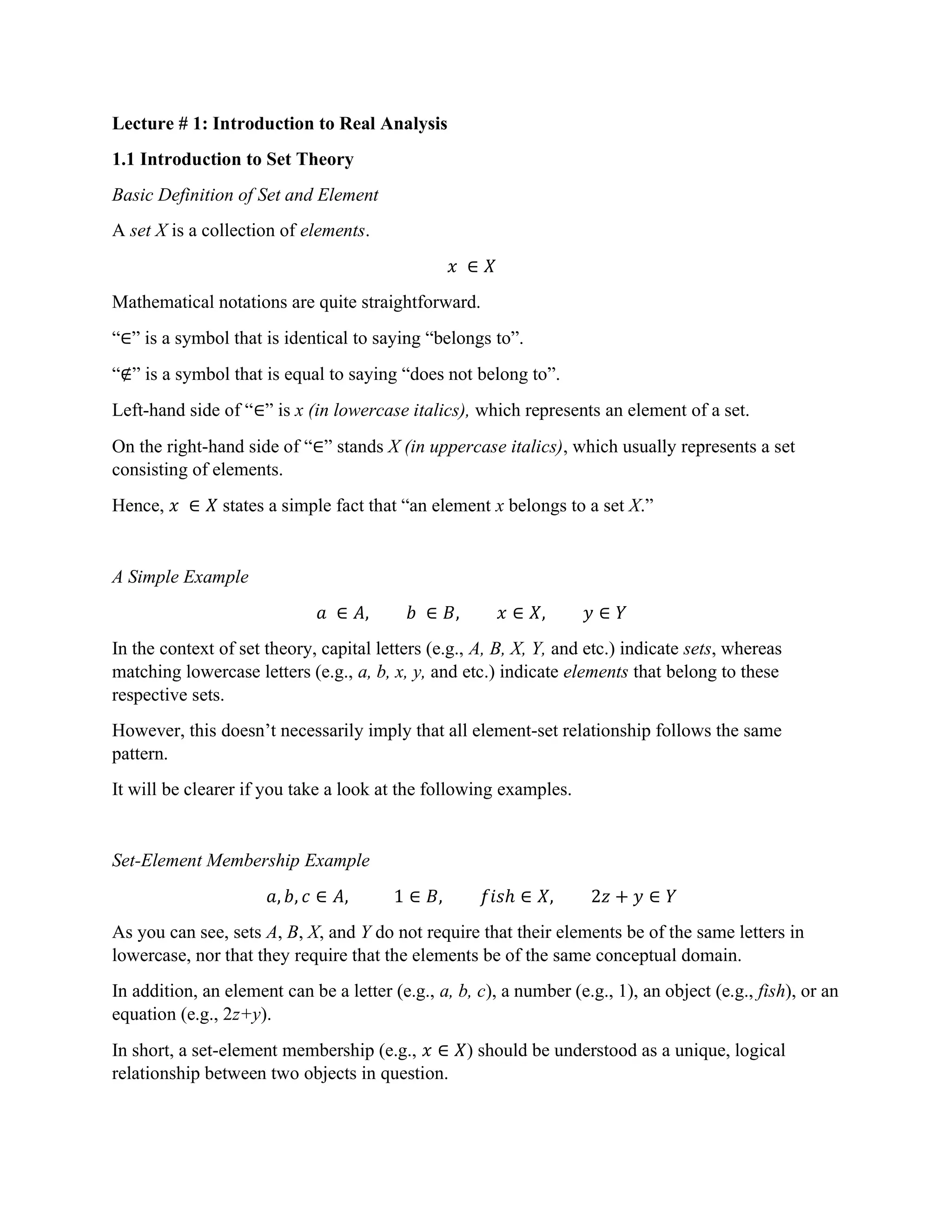

Consider a half-open interval X = (a, b] and a random variable x.

Let us define 𝑎 = −∞ and 𝑏 = 0.

If 𝑥 ∈ 𝑋 and x is any real number, then is 𝑋 a set of all real numbers?

Solution

False. By definition, the set of all real numbers is R = (−∞, ∞).

Since, 𝑥 ∈ 𝑋 and 𝑋 = (−∞, 0], 𝑋 cannot be a set of all real numbers.

In fact, X is a (strict) subset of R. Or equivalently, 𝑋 ⊆ 𝑅 and 𝑋 ⊂ 𝑅, but 𝑋 ≠ 𝑅.

1.5 Set Theory & Real Analysis

Using the mathematical notations that we learned so far, we are able to define explicitly (and

rigorously) numbers using set theory notations.

But first, let’s look at definitions of different types of “numbers” using conversational English

and simple examples.

As you can see above, numbers can be defined into different categories (but not necessarily

distinct; for example, a number 1 is an integer, but at the same time, it’s a counting number,

whole number, and etc.), depending on the characteristics they exhibit.

Imaginary numbers are beyond the scope of this course, so they are excluded from examination.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture1-240514115042-202cd88b/85/mathematics-Lecture-I______________________________-10-320.jpg)

![Q3:

Are the following statements true or false? Please provide a brief proof to bolster your claim.

1) 𝑻 ⊂ 𝑹

2) 𝑻 ⊆ 𝑹

3) 𝑵 ⊆ 𝒁 ⊆ 𝑸 ⊆ 𝑻 ⊆ 𝑹

4) 𝑵 ⊆ 𝒁 ⊆ 𝑸 ⊆ 𝑹 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑻 ⊆ 𝑹

5) 𝑵 ⊂ 𝒁 ⊂ 𝑸 ⊂ 𝑹 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑻 ⊂ 𝑹

Q4:

Let us define 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑎𝑙 𝑥 ∈ 𝑿 and X = (-1, 4]. Are the following statements true? Why or why

not?

1) 𝑥 = −1

2) 𝑥 = 𝜋

3) 𝑥 =

4) 𝑥 = 0

Q5:

Consider a closed interval [a, b] where 𝑎, 𝑏 ∈ 𝑹 and 𝑎 ≤ 𝑏.

We also define real 𝑥 ∈ 𝑿 and X = [a, b].

Part 1:Please provide a concise mathematical definition of X using the set notation “{}” and

inequalities.

Hint: X = [a, b] ≡ {𝑥 ∈ ? : "𝑑𝑒𝑠𝑐𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑒 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑖𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑠 𝑢𝑠𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑥 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑖𝑛𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑎𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠"}

Part 2: Which values of 𝑎 and 𝑏 would make the set X contain only one element in it?

Hint: Providing any numerical example of 𝑎 and 𝑏 is sufficient.

Part 3: Can you think of a specific relationship between 𝑎 and 𝑏 that would make X have only

one element without the loss of generality?

References:

Figure 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5pMN4iA96E

Figure 2: https://www.quora.com/Are-natural-numbers-an-element-of-real-numbers

Tables are from Essential Mathematics for Economic Analysis 4th

Edition, by Sydsaeter,

Hammond, and Strom. Much of the materials that I used in this lecture were excerpted from

Professor Charles Wilson’s lecture notes in ECON-UA06 in 2012 at NYU. Any errors and

inaccuracies due to the recreation of their publishments are my sole responsibility.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture1-240514115042-202cd88b/85/mathematics-Lecture-I______________________________-15-320.jpg)