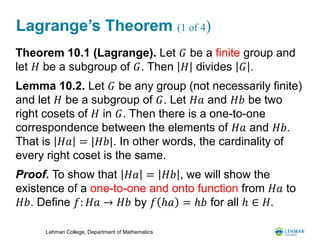

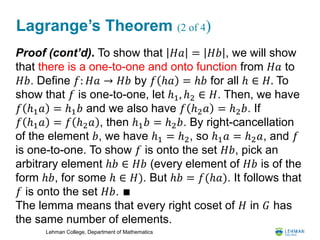

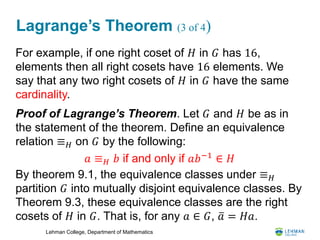

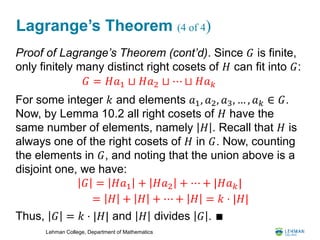

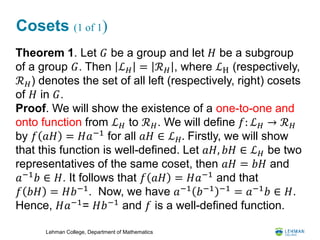

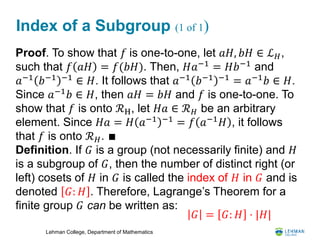

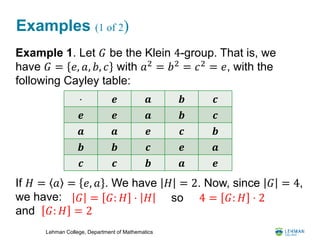

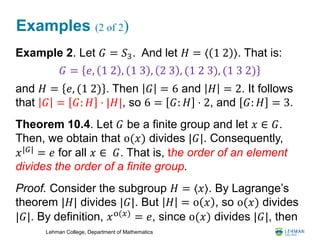

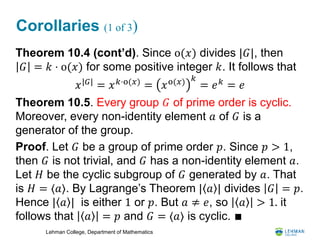

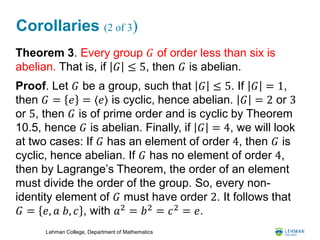

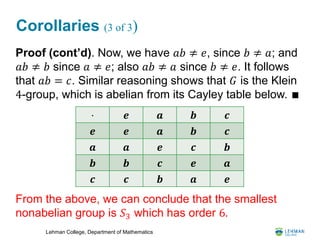

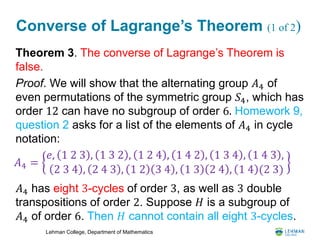

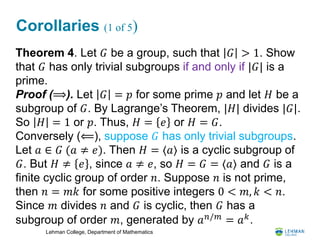

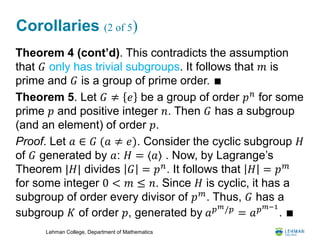

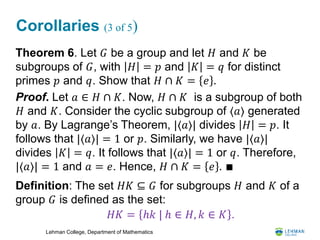

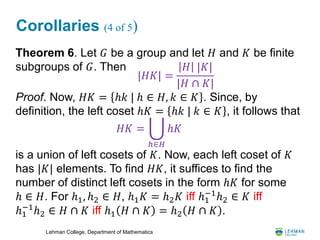

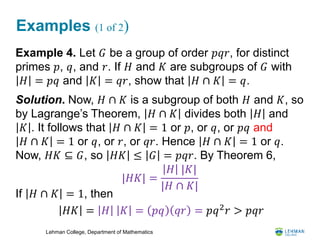

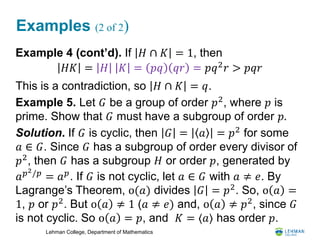

Lagrange's theorem states that for any finite group G and subgroup H of G, the order of H divides the order of G. The document provides the proof of Lagrange's theorem and several examples. It also discusses corollaries, including that every group of prime order is cyclic, every group of order less than 6 is abelian, and the order of an element must divide the group order. However, the converse of Lagrange's theorem is false - there can exist groups where not every divisor of the group order is a possible subgroup order.