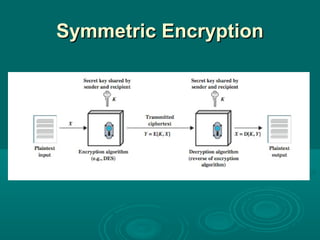

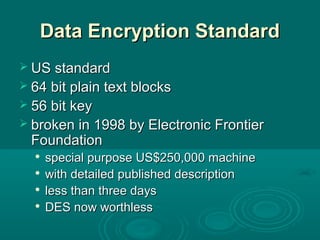

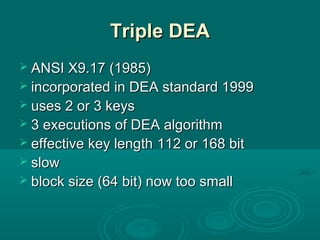

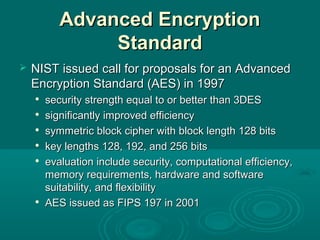

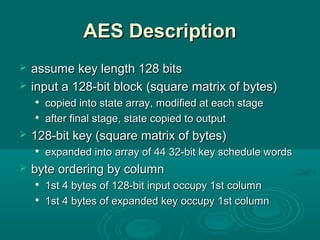

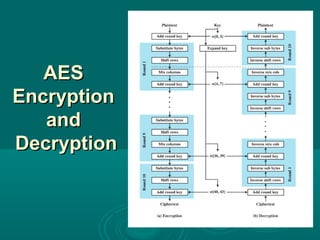

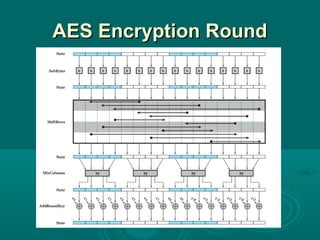

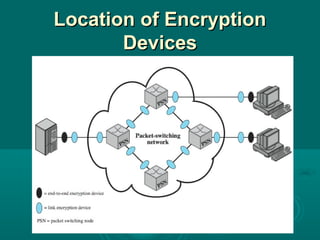

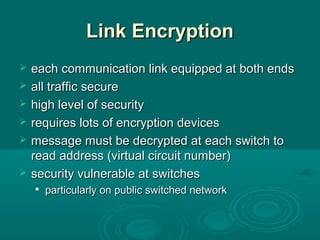

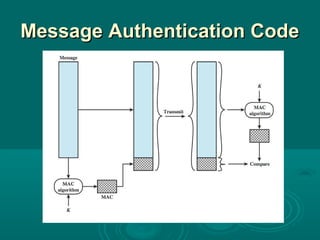

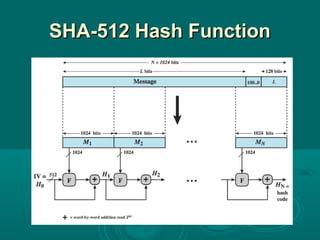

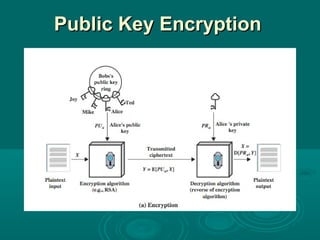

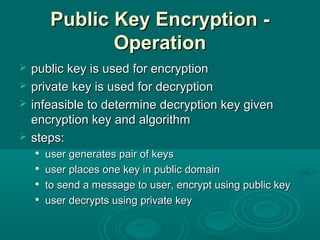

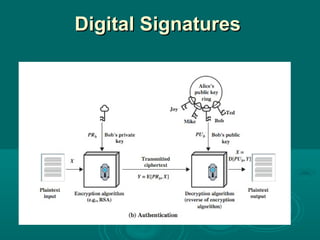

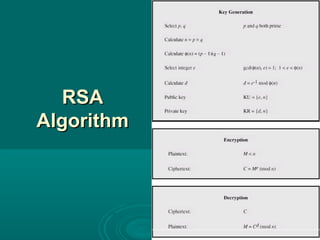

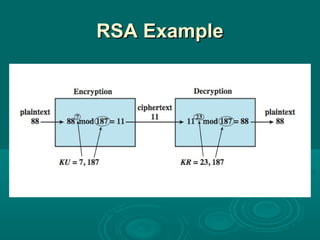

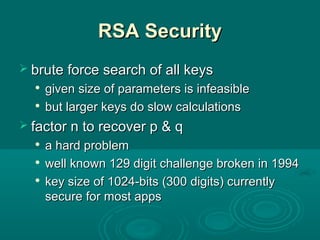

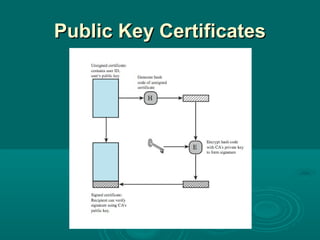

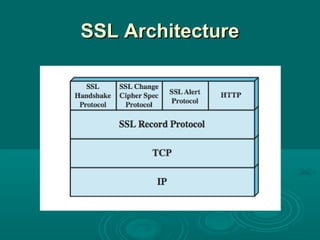

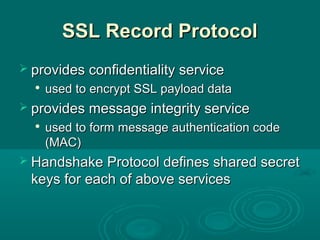

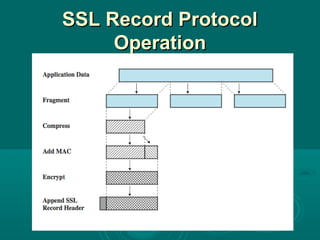

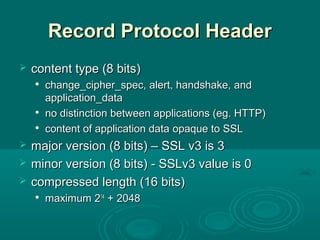

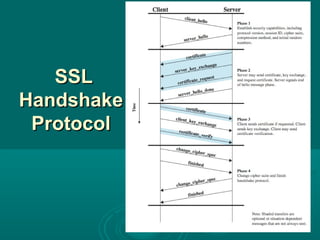

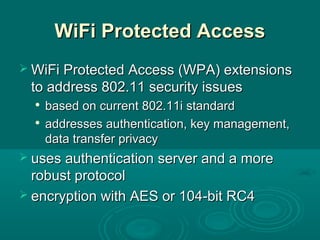

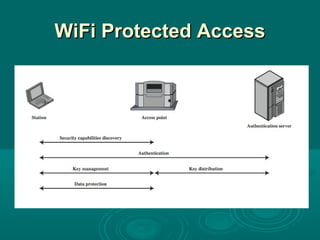

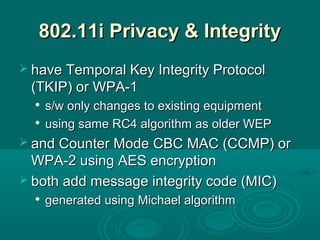

Chapter 21 of William Stallings' book on network security discusses critical security requirements, such as confidentiality, integrity, availability, and authenticity, alongside different types of attacks, including passive and active attacks. It examines encryption methods like symmetric and public key encryption, emphasizing the importance of strong algorithms and key management. The chapter also highlights the role of protocols like SSL and TLS in providing secure communications over networks.