This document provides an overview of ischaemic stroke, including its definition, risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Key points include:

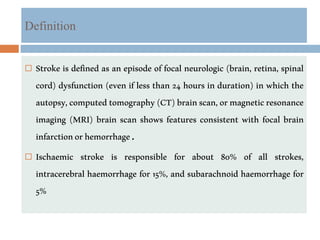

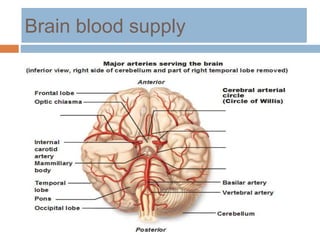

- Ischaemic stroke accounts for 80% of strokes and results from focal brain infarction due to obstruction of cerebral blood flow.

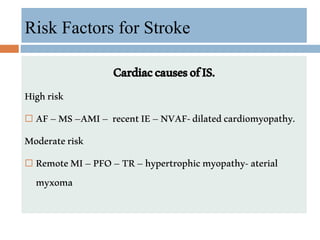

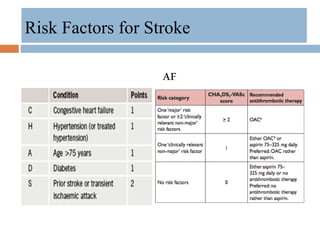

- Major risk factors include hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and previous stroke or TIA.

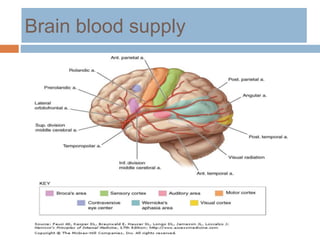

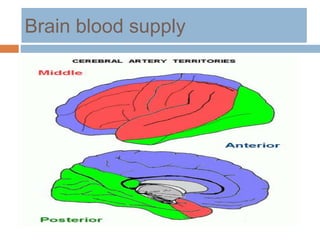

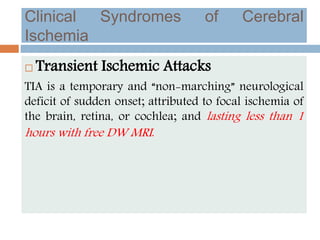

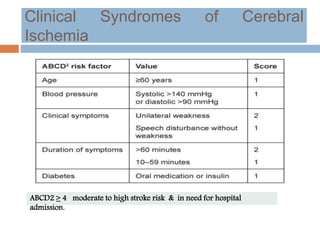

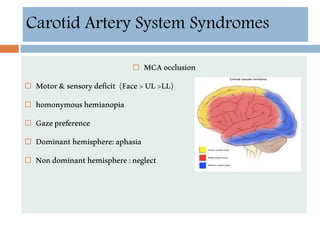

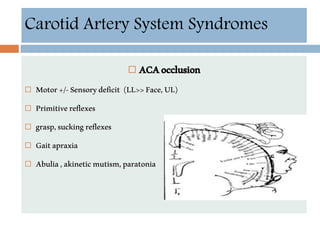

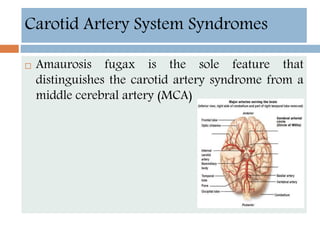

- Clinical syndromes depend on the location of brain infarction and can include motor/sensory deficits, aphasia and visual field cuts.

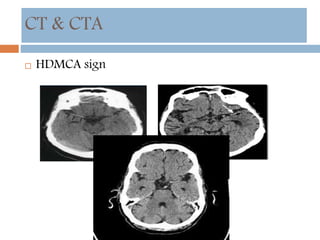

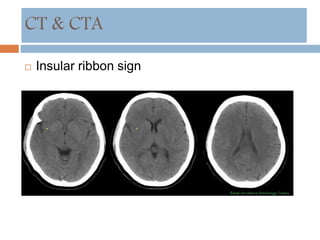

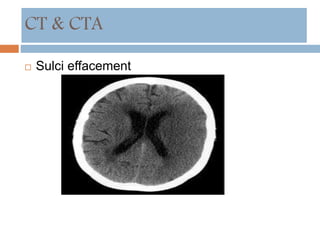

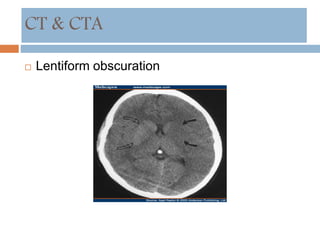

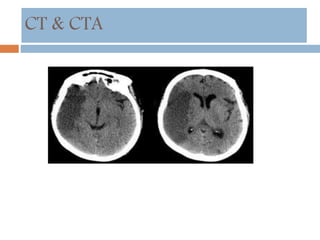

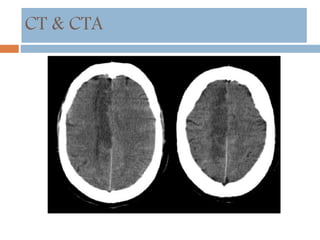

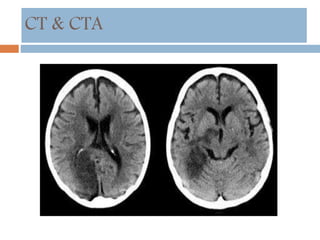

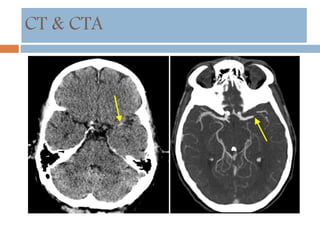

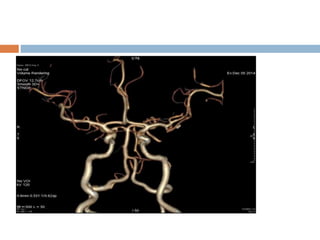

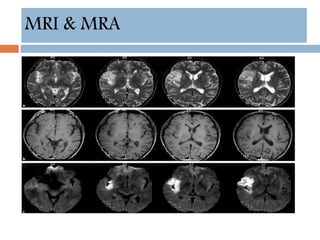

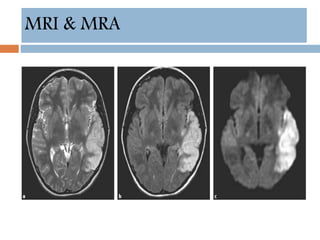

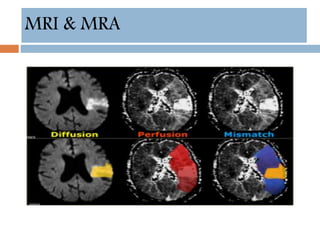

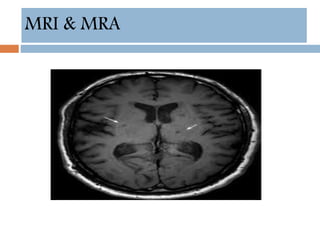

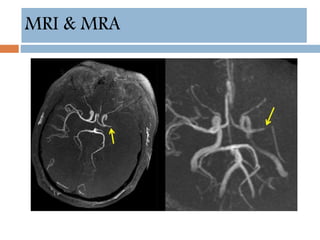

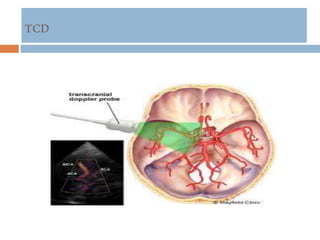

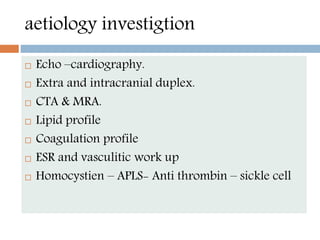

- Diagnosis involves neuroimaging such as CT, MRI and vascular imaging to identify the cause.

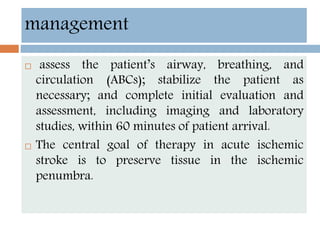

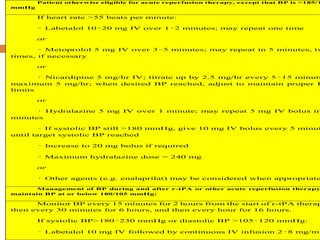

- Acute

![Neuroprotection

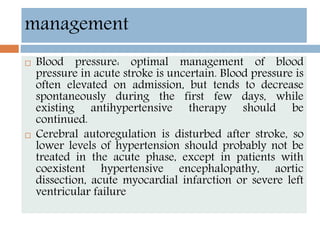

Currently, data are inadequate to justify the

routine use of heparin or other anticoagulants in

the acute management of ischemic stroke.[126]

Patients with embolic stroke who have another

indication for anticoagulation (eg, atrial

fibrillation) may be placed on anticoagulation

therapy nonemergently, with the goal of

preventing further embolic disease; however, the

potential benefits of that intervention must be

weighed against the risk of hemorrhagic

transformation.[1] For more information](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ischaemicstrokeppt-160812010715/85/Ischaemic-stroke-55-320.jpg)