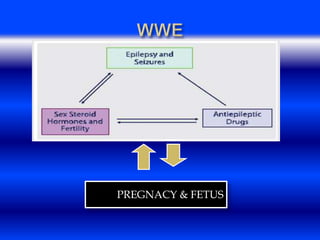

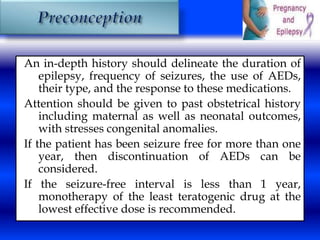

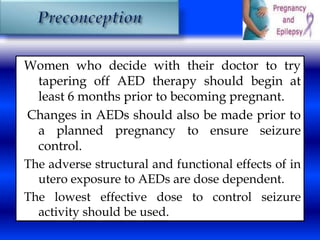

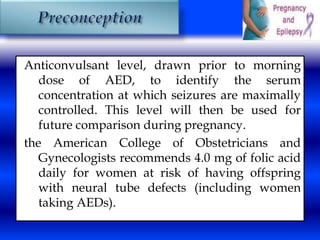

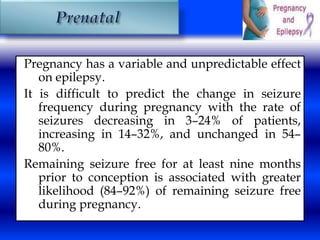

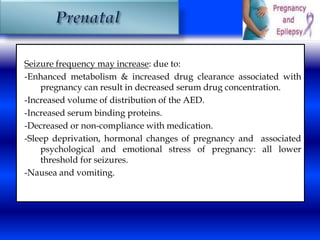

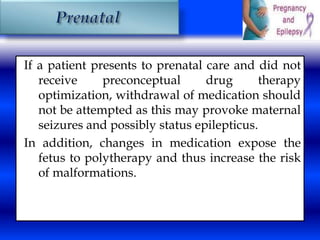

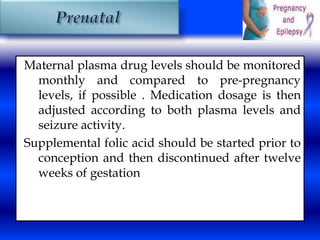

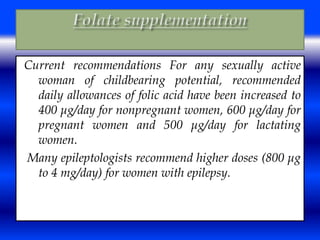

This document discusses the effects of epilepsy and anti-epileptic drug (AED) use on reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes. It notes that women with epilepsy have an increased risk of gestational hypertension, preterm delivery, fetal malformations, and low birthweight infants. During pregnancy, AED levels may decrease due to changes in metabolism and clearance, increasing seizure risk. Close monitoring of drug levels and seizures is recommended during pregnancy to adjust dosages as needed. Folic acid supplementation is also advised to reduce the risk of neural tube defects.

![Women with generalized epilepsy are more at risk for

seizures during delivery than are those with partial

epilepsy .

It is important to remind women with epilepsy to bring

their AEDs to the hospital during labor and to take

regular doses during this period under the

supervision of hospital staff.

Intravenous (Phenobarbital [PB], VPA, LEV)

administration may be needed if the woman is not

able to keep down oral medication.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/osamaepiinpreg-141017154328-conversion-gate02/85/epilepsy-and-pregnancy-53-320.jpg)