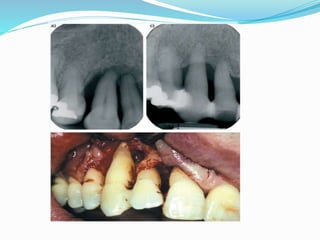

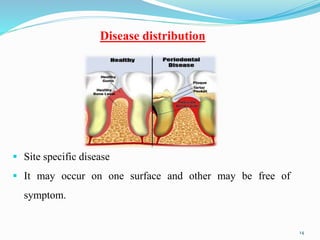

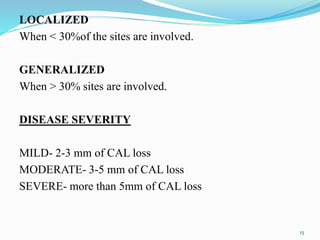

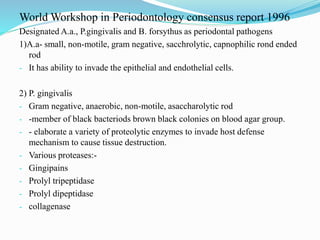

Chronic periodontitis is an inflammatory disease that causes the destruction of tissues that support the teeth. It is caused by an accumulation of plaque and calculus on the teeth over time. It is characterized by pocket formation, attachment loss, and bone loss. Risk factors include smoking, diabetes, and certain bacteria. The disease progresses slowly through periods of destruction and remission. Treatment involves plaque control, scaling and root planing to reduce bacteria and inflammation.