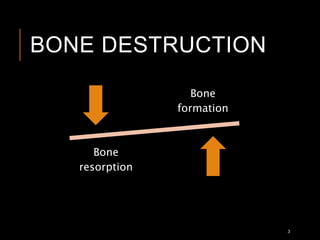

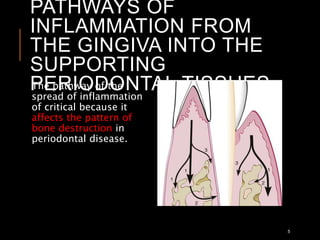

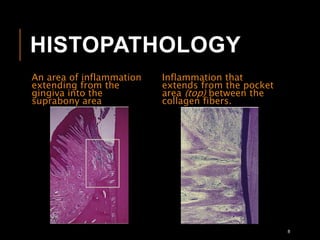

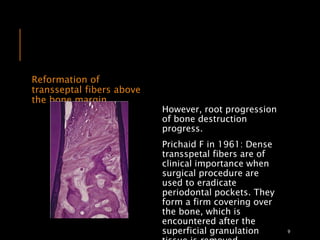

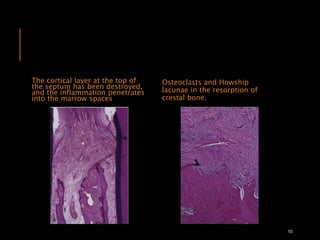

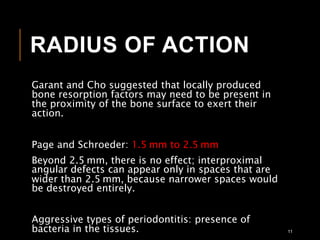

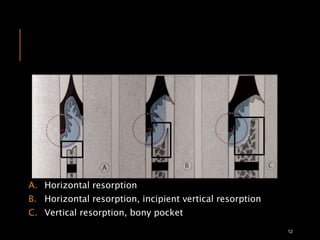

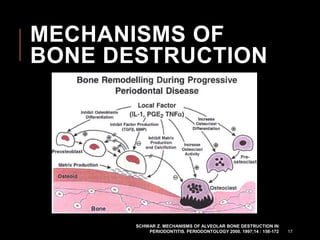

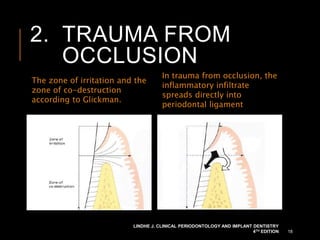

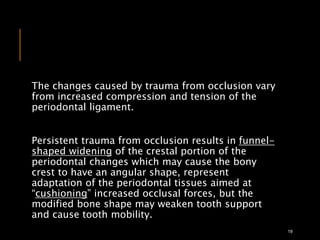

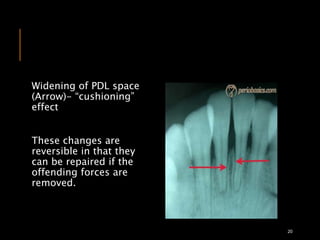

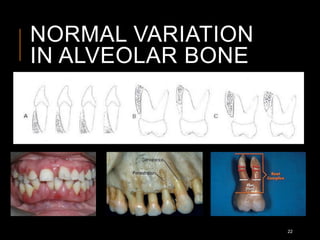

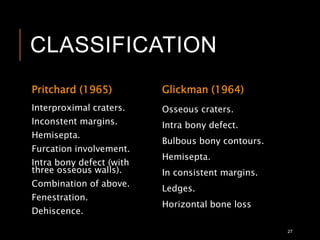

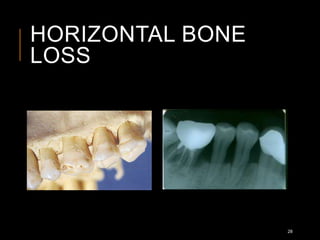

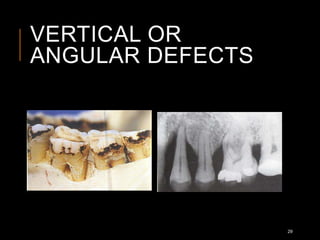

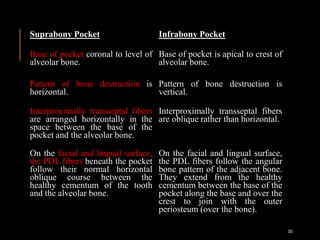

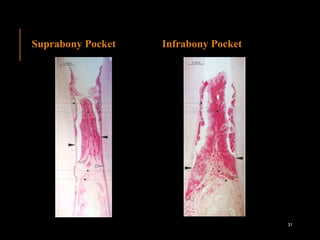

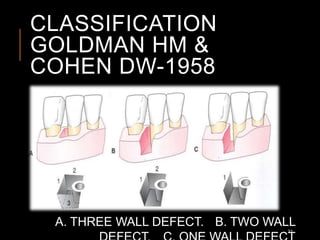

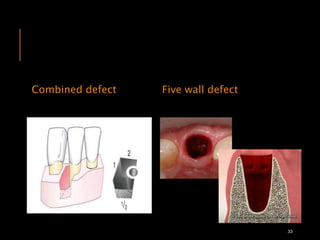

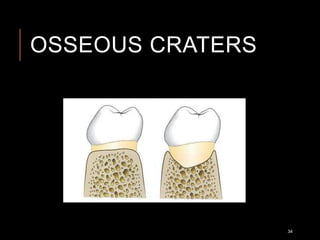

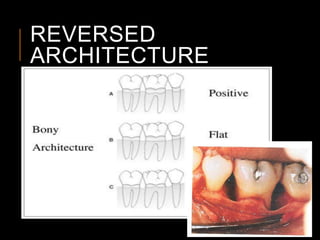

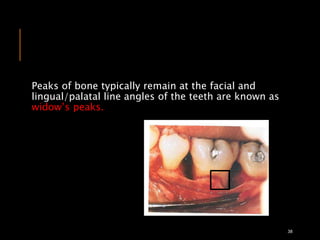

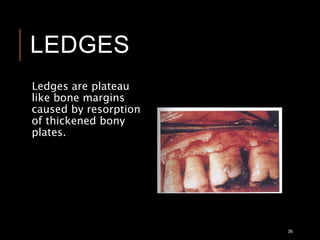

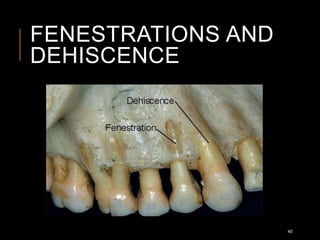

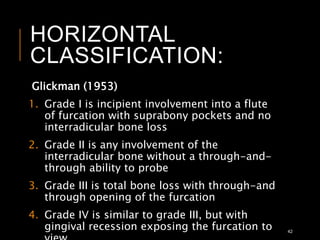

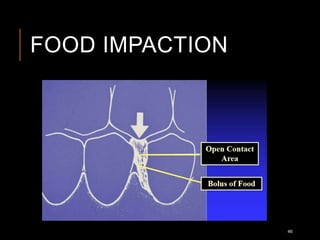

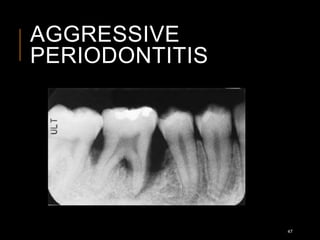

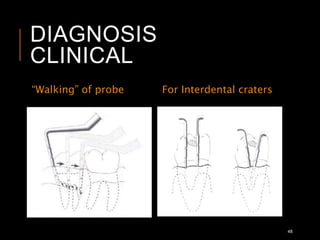

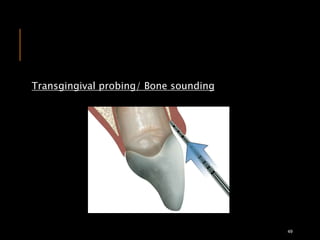

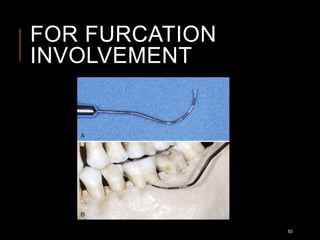

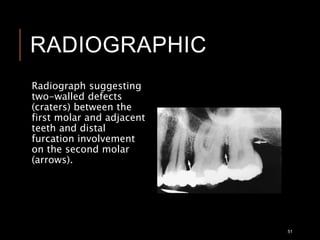

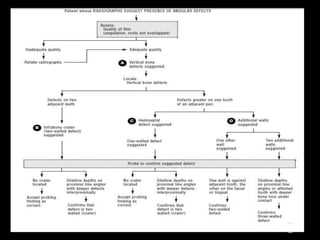

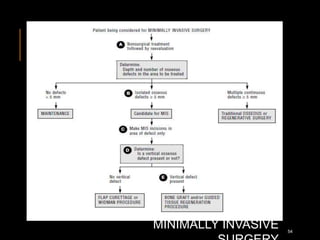

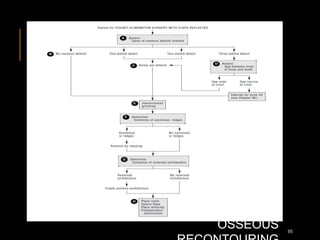

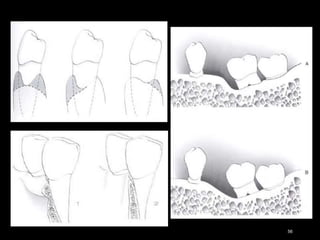

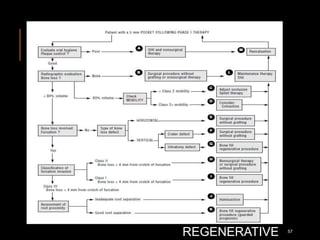

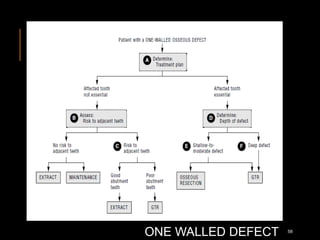

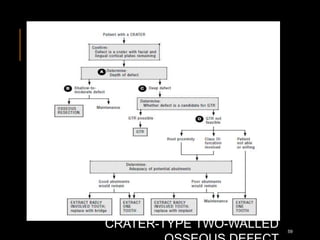

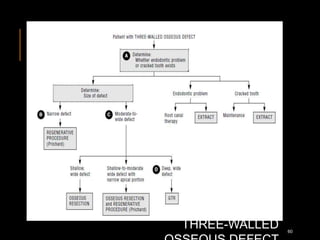

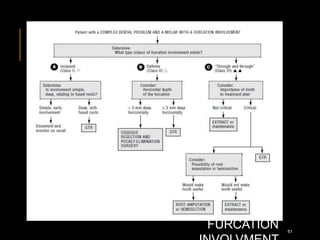

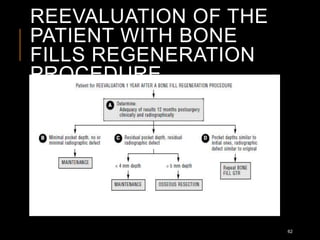

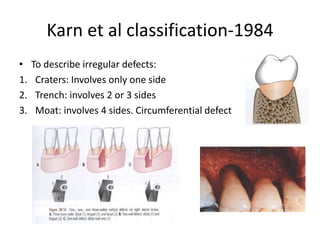

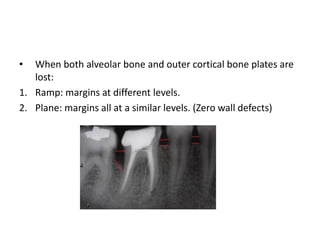

The document discusses the causes and mechanisms of periodontal bone defects, detailing the extent of bone destruction due to gingival inflammation and trauma from occlusion. It outlines patterns of bone destruction, classification of defects, and the impact of periodontal disease on bone morphology, including various types of bone loss and treatment approaches. The document emphasizes the importance of understanding these factors for effective diagnosis and management of periodontal conditions.