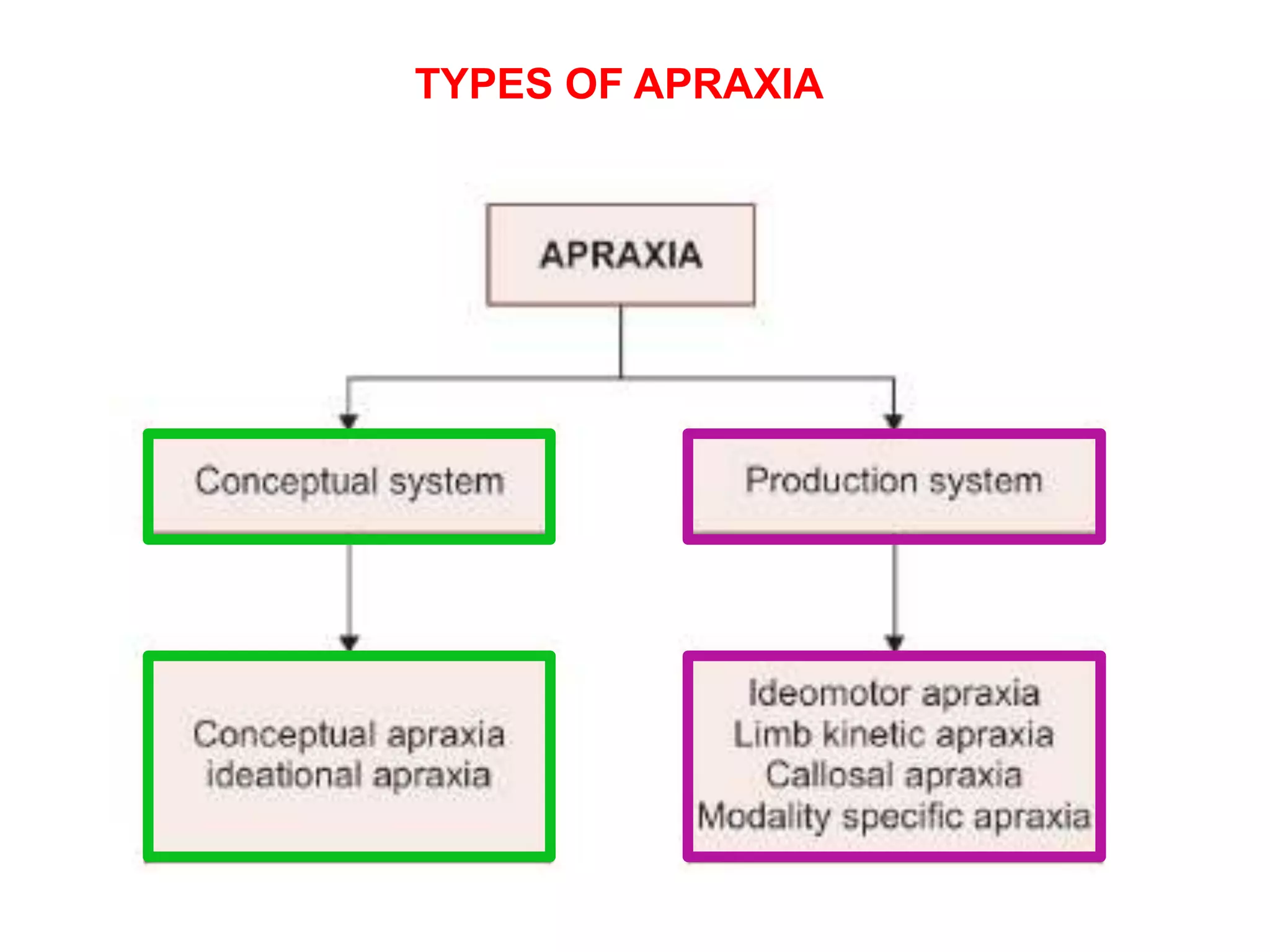

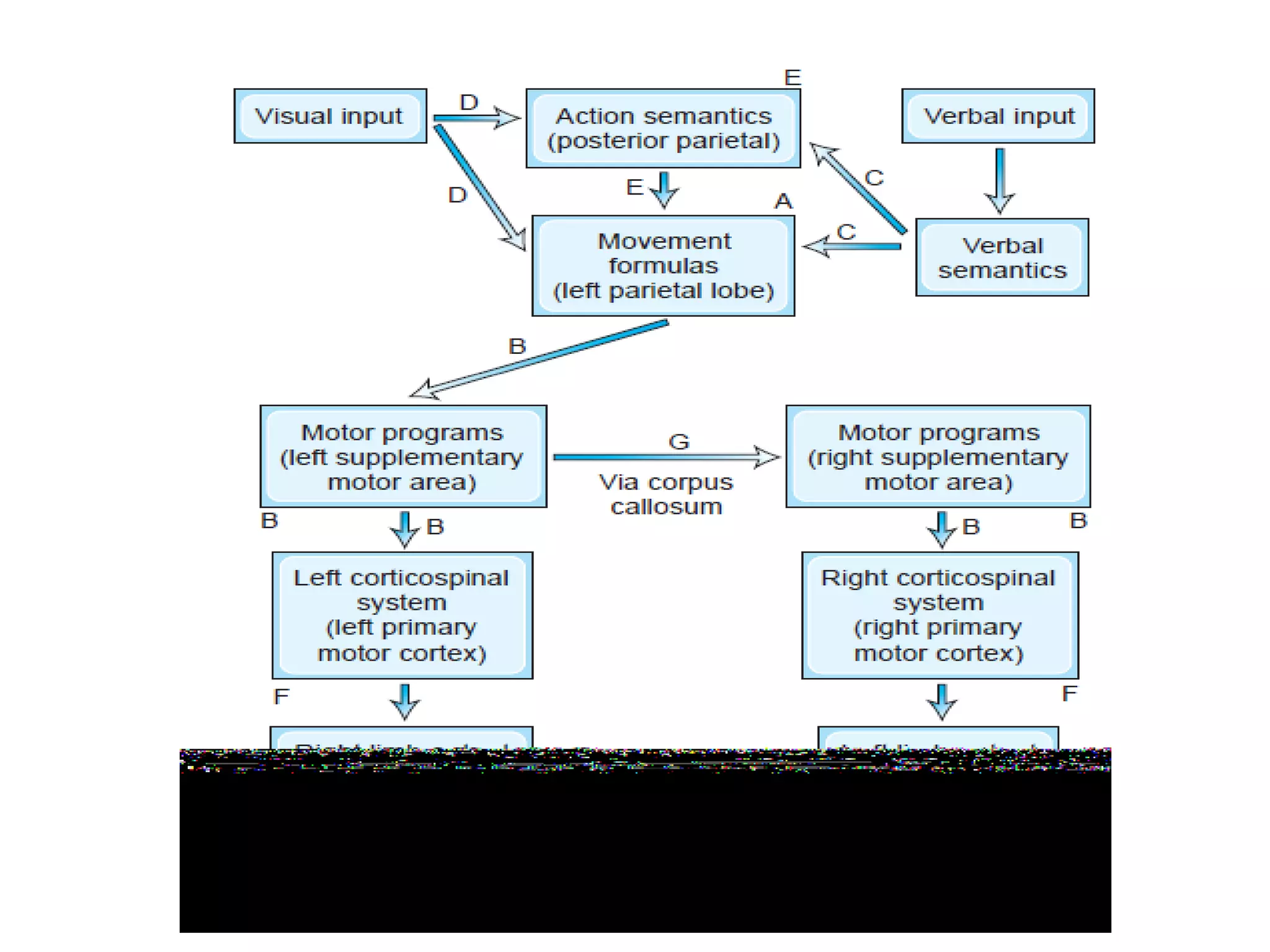

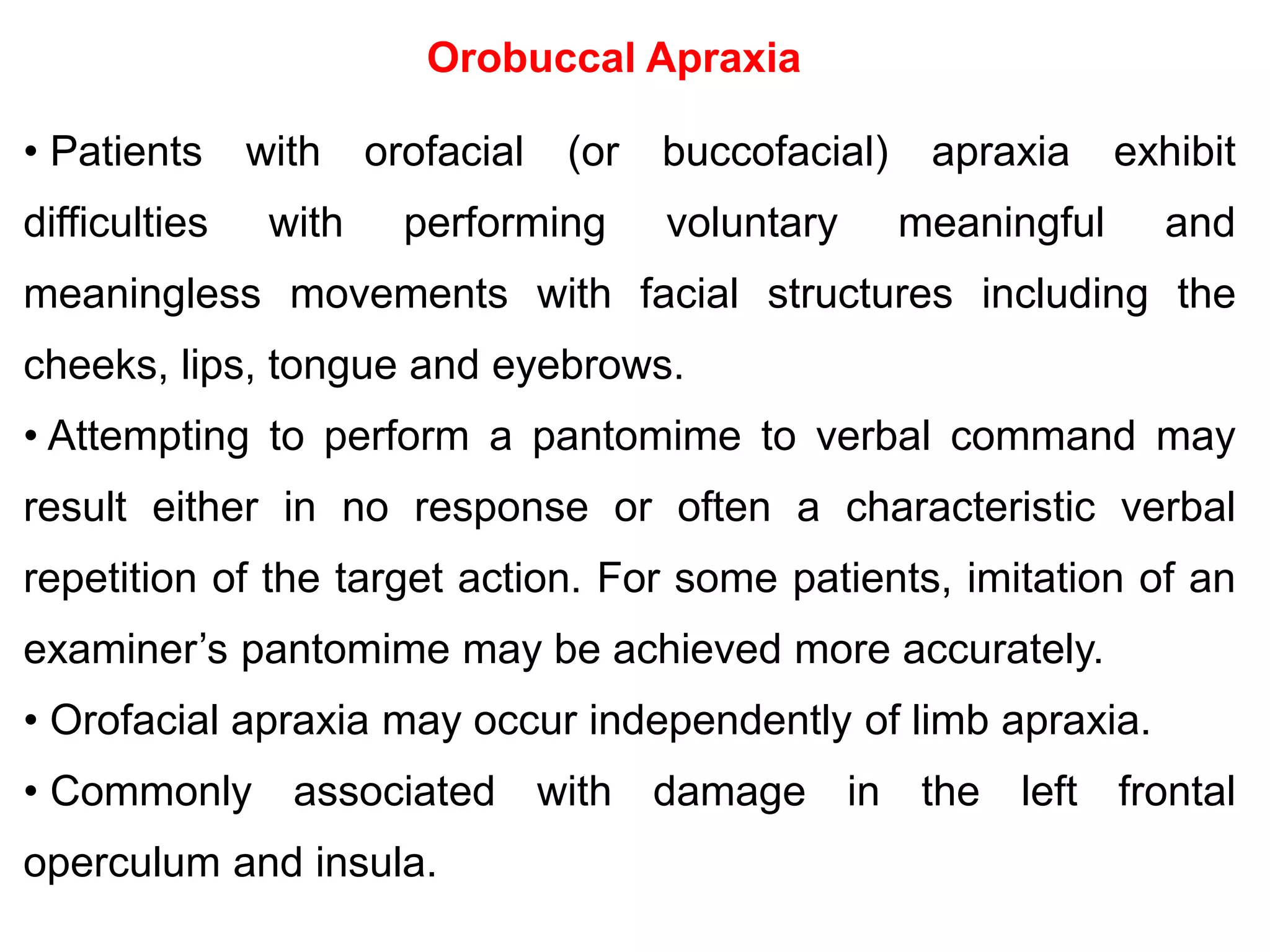

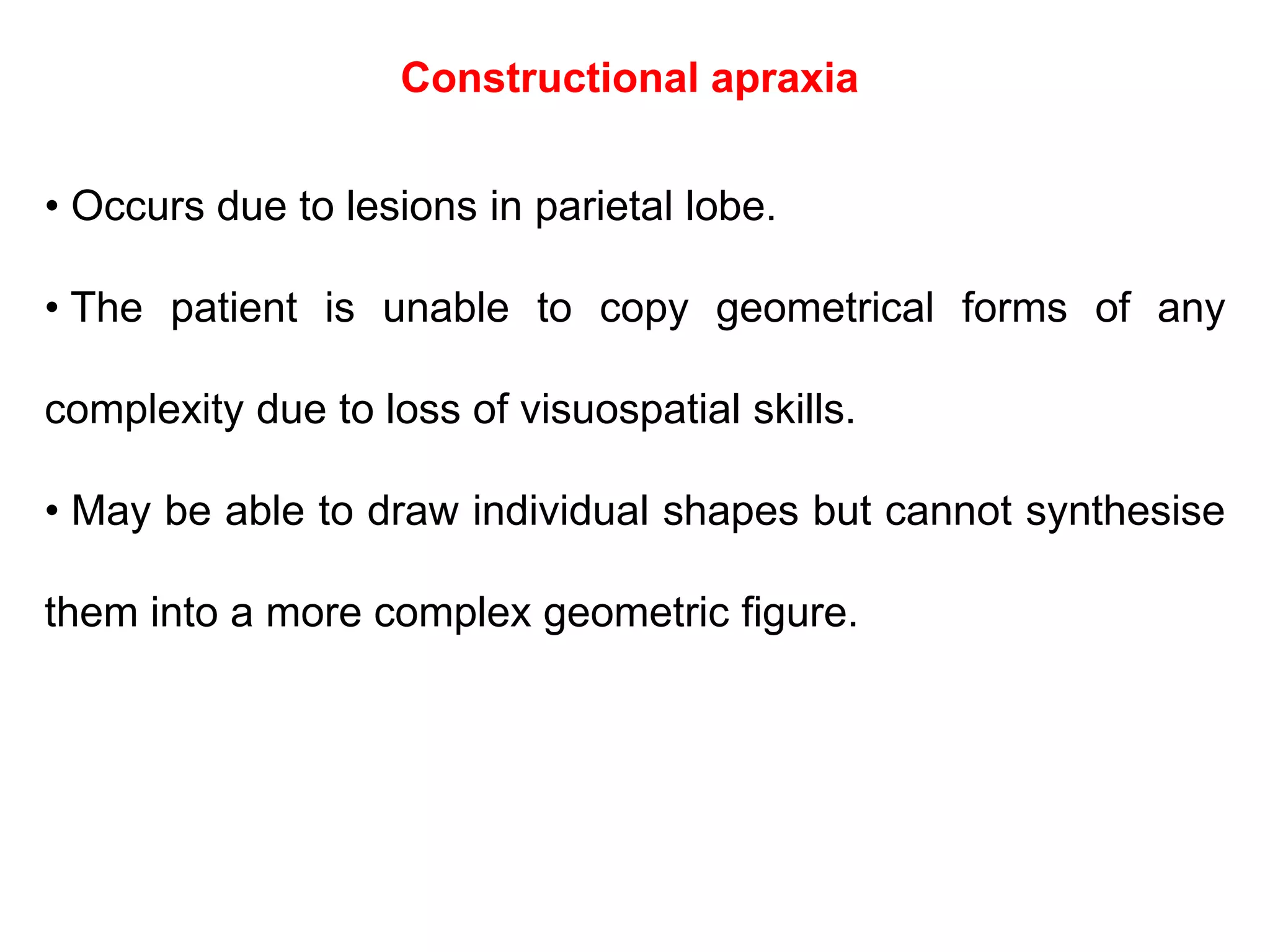

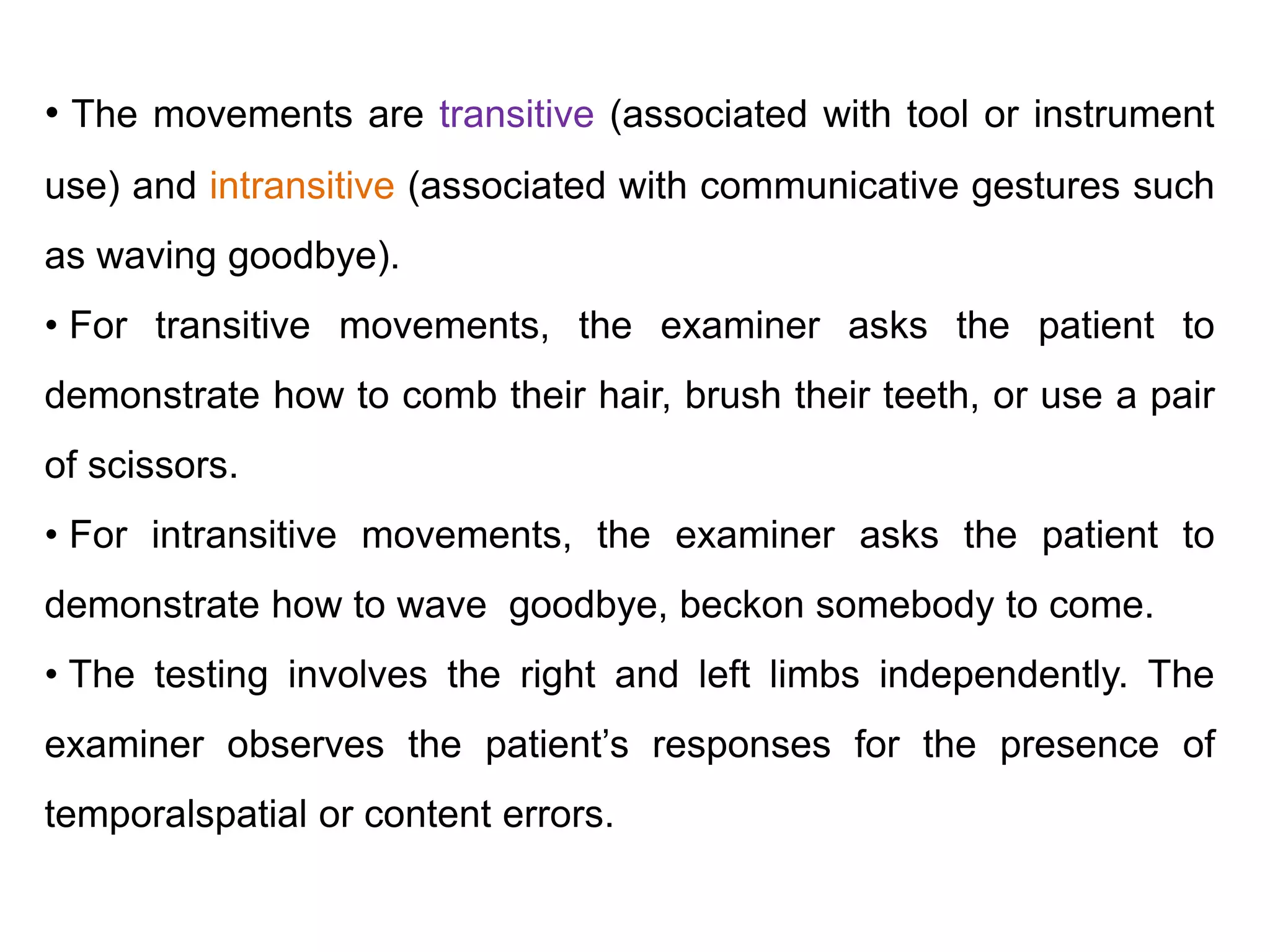

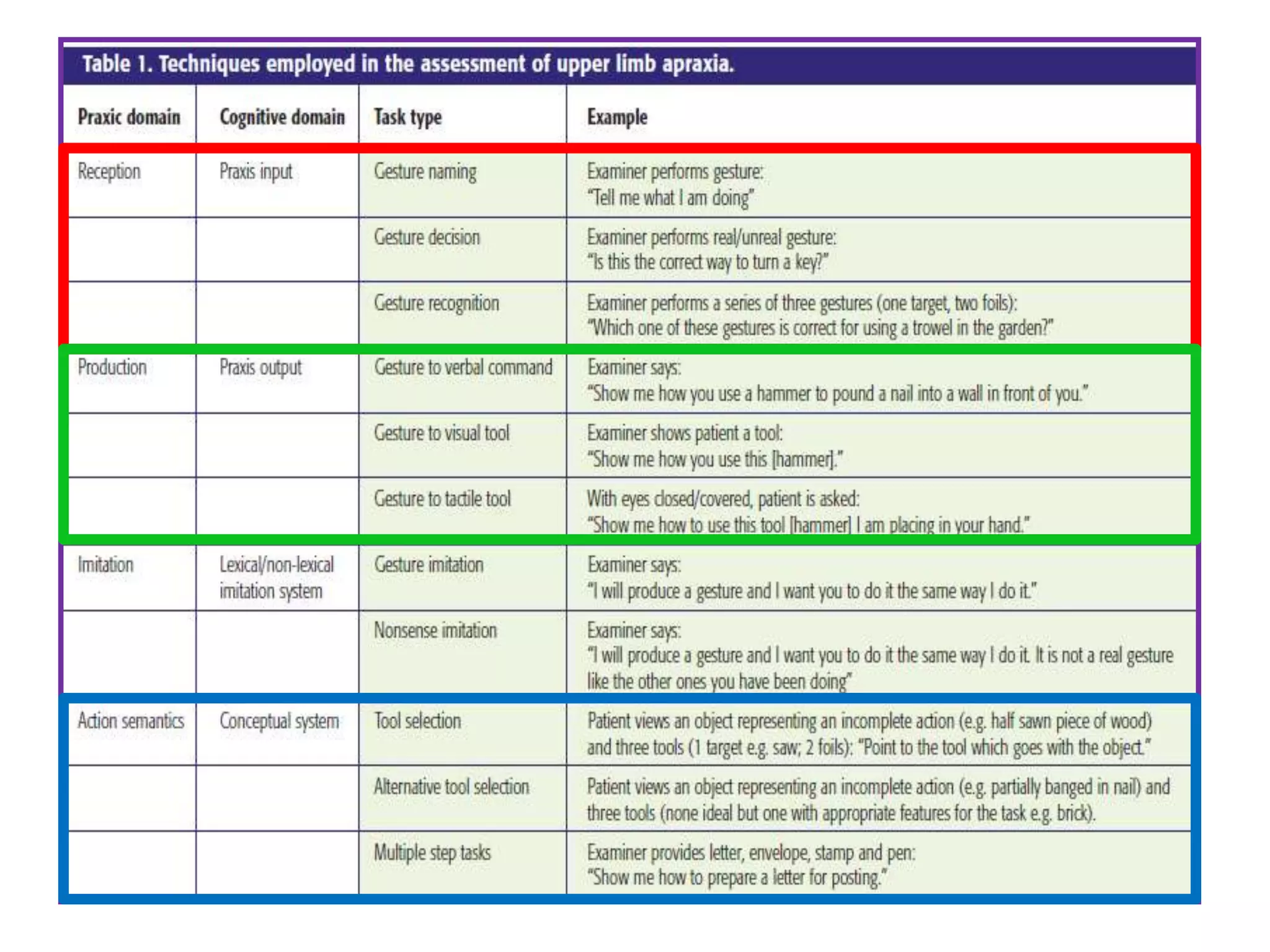

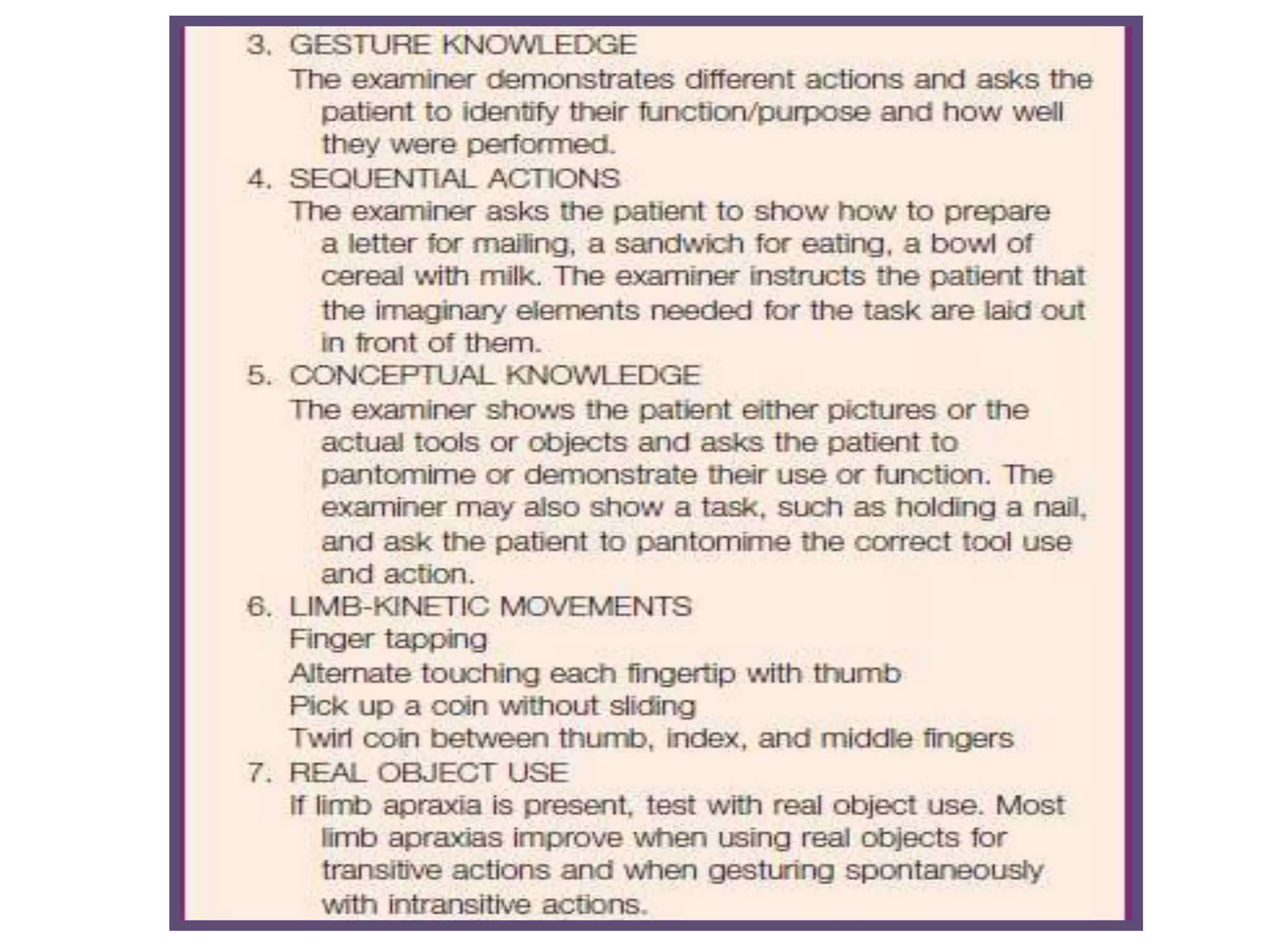

This document discusses apraxia, which is defined as a disorder of skilled movement not caused by other factors such as weakness or intellectual deterioration. There are three main domains of apraxia: defects in pantomiming actions, imitation of gestures, and object manipulation. The document outlines different types of apraxia including ideational apraxia, which is an inability to properly sequence movements, and conceptual apraxia, which involves errors in tool selection or knowledge of tool functions. Neural substrates for praxis are also discussed.